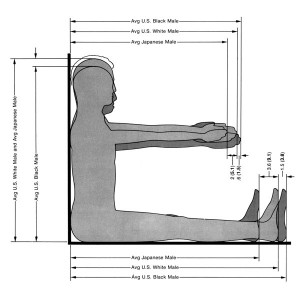

Lafayette Anticipation associate curator Anna Colin talks to artist Tyler Coburn about Ergonomic Futures, a speculative project engaged with art, design, science, anthropology and writing. In this interview, Coburn discusses the research, production process and network of collaborators of a multilayered project ultimately concerned with the futures of humankind. Anna Colin: When one comes across your museum seats Ergonomic Futures (2016—) in contemporary art exhibitions—and soon in natural history, fine art, and anthropology museums—they look… [read more »]

Sonic identity politics with Christine Sun Kim

The social conditioning of deaf people constitutes Christine Sun Kim’s inquiry into the anthropogenic definitions of sound. As a sound artist born without the ability to hear, Kim investigates the sonic as a form of capital, and the currencies it formats in social, cultural, and political life. A former artist-in-residency at the Whitney Museum, she has compared American Sign Language and music in TED talks and was featured in MoMA’s Greater New York, cutting through the stubbornly insular art world categorized as ‘sound art’ with interactive installations that explore the intersection between technology and the sensorial. Kim explores visible and invisible etiquettes of sound – textual, social, visual – as viewers attempt to navigate her often physically-challenging installations.

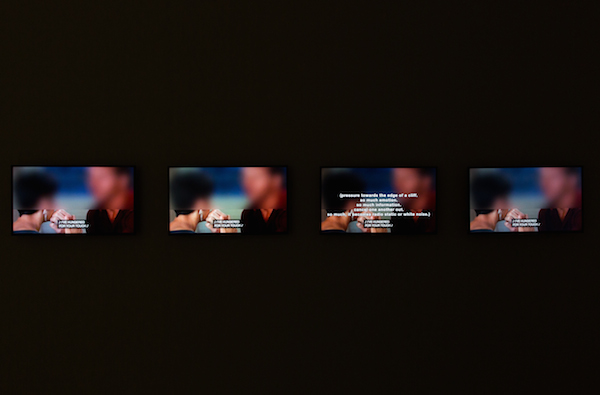

A new series of work, on display at Carroll / Fletcher Gallery in London, deals with mediated sound experiences, as she highlights the curious phenomenon of amplified sound captured by film subtitles. In her treatment of the films 2001: A Space Odyssey and The Little Mermaid (who gave up her voice to live with humans), the descriptions of sound are brought to an extreme by four of Kim’s deaf friends, overloading the spectator with simultaneous visual-auditory impressions. What would usually seem disturbing or excessive becomes a space for sonic subjectivity that reshuffles the hierarchies of sound and the moving image (what’s more important – the protagonist’s monologue or the rustling of the trees in the background?) – a crucial point for the gatekeepers of mediated sound.

Jeppe Ugelvig: In your work, do you approach sound with a consistent definition in mind, for example a scientific (vibration) or musical (symbolic notation, music sheets) definition?

Christine Sun Kim: When I started to consider sound as art, vibration was the first thing that came to mind. After a while, I realised it wasn’t enough and I needed to go beyond its materiality. I began shifting towards other aspects: idea, musicality, social currency, notation, phenomena. I remember the moment in graduate school when I saw a classmate’s hand drawn empty staffs, he was notating a song with staff lines rather than notes, so you could see the weight of each note by looking at each line’s bumps (they’re not very straight lines). That was one of the first realizations I had — how I almost always mirror sound by watching people or interpreters like they’re staff lines, rather than obtaining sound directly like notes. My definition is always evolving, not consistent, and it should be like this.

Christine Sun Kim, Rustle Tustle, installation view, Carroll / Fletcher. Courtesy of the artist and Carroll / Fletcher

Christine Sun Kim, Rustle Tustle, installation view, Carroll / Fletcher. Courtesy of the artist and Carroll / Fletcher

JU: The rhetorical question “If a tree falls in the woods and nobody is there to hear it, does the event create a sequence of waves of pressure that propagate through the air?” suggests an anthropogenic definition of sound (and thus, a definition that is mostly non-queer and socially normative). Do you tackle this in your work?

CSK: It’s weirdly fun for me to discuss sound’s existence; I don’t think it needs a person to recognise its existence. If a sign language interpreter isn’t present to voice my non-sound signing (voice), does that mean my voice doesn’t exist? This might sound super simple, but some people have told me how much they would like to hear my voice (I call that “sonic identity”) when we chat quietly through handwriting on paper or typing on phone not being need to use that dating app . With that said, sound should be able to independently exist on its own… and people are just too hardwired to behave in a certain way around sound.

JU: What was your initial encounter with ‘sound art’ and ‘sound artists’ and the particular paradigms which that part of the art world seems to work within? It seems very rigid to me!

CSK: Ha, tell me about it. I was scared shitless when I decided to work with sound, completely unsure where to start and that made me very insecure when talking with artists about it. For the longest time, I had always perceived it as a hearing thing and that kind of mentality was difficult to change. Deaf people are socially conditioned to put sound in their ownership from the beginning. I was really lucky because in my early career, a string of small grants and residencies started to happen at once, and everyone was super supportive of my practice. That’s when I was able to make so much progress.

However, there seem to be several different responses to my work: people romanticising the idea of me discovering “new sounds” (it’s obviously far fetched; it’s like being expected to find new colours), and others being sceptical or total assholes. It doesn’t help that sound art is relatively new and hard to categorise … everything’s just murky and interdisciplinary that it can be ridiculous to call it ‘sound art,’ because so many artists now use sound in their work, even painters and writers. In a way, everyone is a sound artist.

JU: You’ve previously described sound as an economy, like money or power – of which deaf people would be considered ‘poor’. How might we understand the definition of sound as a socially-constructed?

CSK: Not everyone gets to work with such a large number of interpreters as I do. It feels like the more interpreters I work with, the more social currency I have. People seem to “see” me by listening to interpreters’ voices. I feel very much present among non-signers if my interpreter is doing the job right. If I don’t exercise my place in society by working with other voices, I think my currency as a person/artist gets weakened. On a different note, interpreters aren’t cheap and I am always grateful whenever organisers and institutions are “rich” enough to hire them. That’s a different kind of currency; my interpreters need to be paid with money currency in order to act as my sonic voice so that my social currency increases. The bottom line is that non-sound languages need to be in the same place as sound languages.

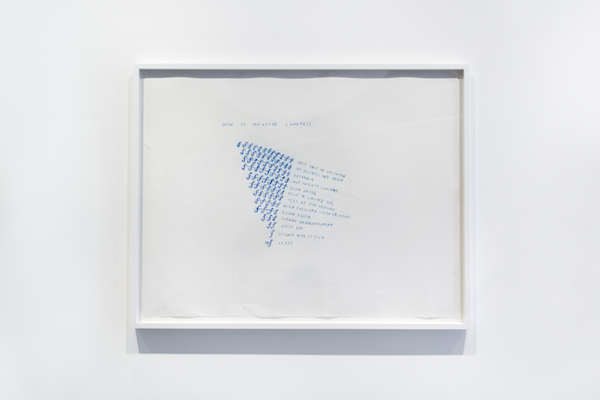

Christine Sun Kim, How to Measure Loudness, 2014, Dry pastel and pencil on paper

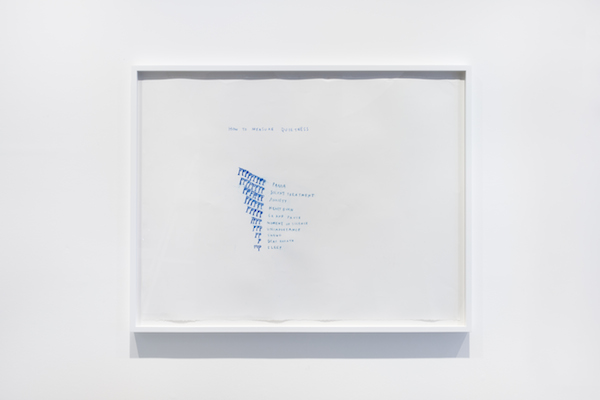

Christine Sun Kim, How to Measure Quietness, 2014, Dry pastel and pencil on paper

JU: What do you mean with the notion ‘sound etiquette’?

CSK: When you try to be quiet out of respect for others, that’s sound etiquette. I’m pretty mindful and maybe a bit too conscious on my part: walk quietly when somebody’s asleep, eat quietly in front of others, no sound during classes, etc. Sometimes I bend these “rules” when I’m with a group of deaf friends by being a little loud, moving around a lot, etc. If I was the only signer in the group of non-signers, I move much less and have super intimate conversations with people through typing on the phone one to one.

JU: I was really taken with your video installation that uses A Space Odyssey and The Little Mermaid. Why did you choose those two films? Can you tell me about what led you to making this piece?

CSK: Thank you! It’s my first video project and this is definitely a new direction in my work. This came from the experience of watching Kumieko, the Treasure Hunter and I found myself reading instead of watching. Their captioner went overboard (it’s a good thing!) and tried to capture every sound: the sound of a man scribbling on paper, the sound of rain hitting window, of the city waking up, and so on. They were beautifully abstract and imposing. My understanding of sound largely depends on each movie’s captioner and their selection of sounds, just like my relationship with sign language interpreters. For example, they would interpret a teacher’s lecture and not mention some kids gossiping at a corner: it’s like second hand selected listening.

So for Close Readings, there are five movie scenes in total and they all resonate with the theme of voice. 2001 is partially about a machine taking over the spaceship and making decisions without astronauts. The Little Mermaid is one of my all time favourite childhood movies (although I feel pretty conflicted about it now, for feminist reasons) and Ariel the mermaid basically gave up her voice in order to get a pair of walking legs, so she could assimilate with walking humans (which is eerily similar to some of deaf experiences). I put all five scenes together and invited four deaf friends to add their sound captions.

Christine Sun Kim, Close Readings, 2015, 4-channel video Courtesy of the artist and Carroll / Fletcher

Christine Sun Kim, Close Readings, Film still, 2015.

Christine Sun Kim, Close Readings, Film still, 2015.

JU: For me, the immediate reaction to this piece was a feeling of violence – of bringing-forth or amplifying sounds that would normally be ignored. It reveals a kind of everyday audial editing of sensual stimuli (in this case, film and the normative vernacular of subtitles), particular when mediated through media. It was incredibly powerful.

CSK: Yes, sound is so incredibly multi-dimensional that it’s mind-blowing for me to imagine a captioner trying to encapsulate it into very few words. There is always “ominous music” going on and sometimes movies just describe it as “music,” at which point I would miss the warning that something nasty is about to happen. I also would like to see more subtle cues such as describing a character’s voice: female, low-pitched, heavy accented, normal volume, a lot of pauses, etc.

JU: Why did you choose to blur parts of the screen?

CSK: It’s not really about movie scenes themselves, so I wanted to partially blur the screen and encourage the viewers to read instead of watching.

Christine Sun Kim, Game of Skill 1.0, 2015, Velcro, magnets, custom electronics, sound file