My Sole, On the Sidewalk | Miami-Dutch

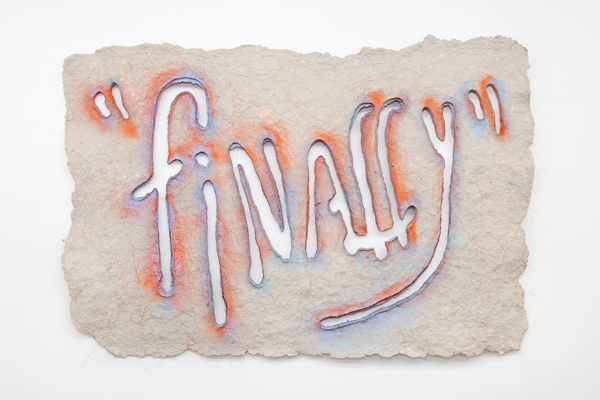

Flower petals are sprinkled like debris and time passed is preserved like fossils in sedimentary rocks in Miami Dutch’s first New York solo show, My Sole, On the Sidewalk which was on view through December 13 at Shoot the Lobster gallery. From the items deposited in a wax trough to the pulpy handmade paper banner across which “finally” is scrawled, the thread of layers and leftovers throughout the exhibition gestures at a moment of looking simultaneously into the past and future, when pre and post are both visible at once.

The first thing you notice upon arriving at the LES gallery space is the neon sign in the window illustrating the collective’s chosen mark of authorship, a six-fingered hand. Miami Dutch is made up of SAIC grads Lauren Elder, Brian Khek, André Lenox, Evan Lenox, and Micah Schippa. The group, who today find themselves scattered across New York, Chicago, and LA, have been working collaboratively for about six years (at one point under the name No-New.Info). Under the earlier moniker, their work was marked by corporate aesthetics and a more explicit engagement with tech, but since the name change, their practice has matured into an exploration of post-national identities and community politics, looking back past brand logos to other defining symbols like family crests and coats of arms. Their name, referencing two languages, the waning Native American language Miami-Illinois and the extinct colonial dialect Jersey Dutch, suggests their sustained interest in forgotten American histories as well as how communication systems function in a post-national world. We spoke with the “post-identity” collective about capitalism, migration, and the mental mindfuck of today’s temporal extremes.

Whitney Mallett: Do you think we’ve maxed out on critiquing corporate brands by emulating them? Was that part of the shift for you guys from No-New.Info to Miami Dutch?

Miami Dutch: Participating in capitalism to that degree, even in a critical way, didn’t feel productive. We felt that No-New.Info pigeon-holed us into a specific conversation, and liked the way that Miami-Dutch acted as a departure towards a larger conversation surrounding colonialism, migration and emigration, individualism, mob mentality, and memory.

Brian Khek: Another issue we had was that this notion of critiquing bureaucratic structures and capitalist cultures felt so exclusively Western that we wanted to explore other notions of collectivism, like ideas of nationality and issues that are more intrinsically global.

Micah Schippa: We also all used to live together and share studios; as a result our artistic and emotional identities started to coalesce, pull apart, and come together again. I think this is when we shifted from being a collective to actually collaborating. We were constantly being forced to negotiate where our bodies began, and where our collaborators’ bodies began.

Miami-Dutch, Untitled, 2015, Newspaper pulp, abaca fber, abaca pulp, spray paint, 40 x 59 x .5 inches (101.60 x 149.86 x 1.27 cm), Unique

WM: What draws you to playing with different languages and communication systems in your work?

Evan Lenox: Through language (and symbology) we are able to form a fictional culture/civilization/group.

MD: This brought us to make our debut piece as Miami Dutch, as part of a group exhibition curated by Harry Burke at Library Plus in London titled Insitute Bianche. We played an anthem named after our slogan, One Body, One Hand (sung by opera singer Deenah Bassiouny in Chicago) on a boombox in the London space, while performer Melika Ngombe Kolongo lip synced.

BK: A lot of people ask me why we make this sort of work given that a lot of these ideas obviously existed before the technologies we are confronting in our practice. I think this is an important time to reexamine what the definitions of a culture or a community are. We are witnessing the capacity of displaced people to create a sense of unified identity regardless of geography. For this reason it’s important for us to create physical works that point you to the very real condition of being in a physical location and experiencing things locally.

Miami-Dutch, Trough (detail), 2015, Stainless steel, beeswax, paraffn wax, oak, fowers, fsh bone, paper,

earrings, shoelace, 18.75 x 48 x 15 inches (47.63 x 121.92 x 38.10 cm), Unique

WM: Does technology play into this? I’m thinking about how these identities are helped along by technology, for example people keeping in touch with their family via Skype when they are separated for political reasons by borders, but also how the internet allows the past, present, and future to all exist at the same time to some degree.

André Lenox: When we were doing research for this show, we were looking at the work of Milan Kundera, whose early writing emerged from the Prague Spring — a period of Communist reformation and nonviolent liberation from the Soviet Union… Kundera spoke of time in an intriguing way. He was concerned less with the Prague Spring than with the Prague Autumn, and asserted that the events that transpire post-revolution are more significant than the revolution itself.

EL: This relates directly to the “finally” piece, which was inspired by an Anthony Bourdain Netflix episode taking place in Libya after the fall of Gaddafi. There was this great shot where Bourdain was driving in a car and passing a mural that read “Finally, We Are Free.” And we all loved the simplicity of that phrase, and decided to abstract it and make the event that has just occurred unclear while suggesting this cathartic breath or giant sigh. After the sigh comes the autumn.

MS: We live in this where we are being force-fed by western neoliberalism to believe that we’ve entered a technological Golden Age. But a lot of people are conscious of dystopic narratives as well, especially our generation who grew up with The Matrix and that one Tom Cruise movie Minority Report! Sometimes I do believe in this technological future but at the same time we have refugee crises in Syria that are so alarming. We have this pseudo-Soviet era [rivalry] with Russia [and the US]. It feels like the decades surrounding the world wars. It’s temporally really drastic. For kids who grew up in America, it’s an absurd mental fuck when it comes to time because you look around and it feels like you are simultaneously living in the past and the future. It’s really confusing.

Lauren Elder: There’s a narrative in playing with this idea of myth—the mythic nature of identity, where we came from and where we’re going, and what defines us, or what does not. One thing we do is imagine ourselves as our own nation, or governing body, even if only in the broadest sense. We work with our imagined myth and how that can influence our perceptions of the past, present, and future. We can gather all theses separate stories/information from everywhere and generate our own content from different perspectives. With information that is being presented, every person naturally generates their own story. Then you read all these other articles online, which a lot of times are skewed just to get higher ratings, which then produces a whole other pantheon of myths. With time and technology there is a generative sense of myth.

BK: These myths act as a structure to refer to. It’s like the guidebook when everything is in chaos. That’s why we are interested in anachronistic cultures where people are rejecting contemporary lifestyles, you can kind of rationalize that in that same anxiety where people are afraid to commit to current technology.

Miami-Dutch, Down From the Mountain, 2015, Archival inkjet print, 31 x 31 inches (78.74 x 78.74 cm) (frame). Unique

WM: Are narratives tools? Is the way out of this chaos to imagine new stories? Donna Haraway talks about this a lot, how we are only going to change things if we have narratives to help us.

EL: Definitely. The title of the wax seal, Down from the Mountain, is used as a form of narrative, implying that there is literally a body of individuals on top of a mountain formulating a new identity. The symbols are borrowed from escutcheonry and heraldry, and are incorporated with contemporary imagery, as a way of creating a fictionalized sense of self. It is the first thing that happens after the event (be it the fall of a political entity, or the end of a dictatorship). The said event remains unclear, but the stamped seal on wax is meant to suggest that there is a future.

AL: The mountain scenario — which we’ve incorporated into several of our press releases — references contemporary folklore surrounding an international magical order, the Illuminates of Thanateros (IOT). The text is grossly melodramatic, and could fall anywhere on a scale from fiction to historical document. Regardless of authenticity, the narrative has potential to exist in any temporal or spatial context; through the embodiment and repetition of this narrative, we allow ourselves to regroup, rebrand, and even colonize the collective itself.

BK: The trough piece also uses narrative, using a lot of references directly from the seals we designed. The trough is kind of a Frankenstein of all those things. The legs of the trough reference these mid-century modern animal legs. We put a fish in the trough. There’s flowers in the trough. News clippings. This piece conceived most of the conversations for the other pieces in the show. We were looking at public urinals; we also tried to make references to this in the press release. We liked how peeing was this super animal and territorial act. Plumbing is also critical for urbanization and civilization.

WM:

Has capitalism replaced culture in American society? Are you trying to troubleshoot and find other ways of identifying other than as a consumer by looking back at these different modes of identity-building like myths, folklore, family seals, dialects, etc. throughout history?

BK: Part of what we are pointing to is that exactly how other people usurp these cultural histories… and it’s a question a lot of us have to confront personally. Like if I go to Cambodia, I’m not a Cambodian. But here, I’m not exactly American either. I think that’s a very American sentiment, not even just in our group but generationally. This idea of experiencing culture second-hand or through the news or through literature is something we try to represent in our work.

AL: These experiences have been passed-down familially as well. For instance, Evan, Lauren, and I are all part Arab. Lauren is half Iraqi-Jewish. Evan and I are each a quarter Palestinian. Ethnic fractions aside, the idea of the wandering Arab has still been verbalized and embodied through nurture.

EL: Our work has a lot to do with traveling, not being near one’s familial place, not being settled, being in motion, en route, etc., be it through leisurely travel or forced emigration. This is where our rolling suitcase piece comes in. Titled Ghost Bag, the suitcase is kind of distressed, cast in aqua resin and fiberglass and embellished with flowers, in reference to a “ghost bike” memorial that appears on the side of the road after a pedestrian is hit by a car. The piece becomes this kind of memorial for a traveler or migrant body.

WM: As I’m asking you to explain your show to some degree, I’m really self-conscious of the trap of finding an easy formula of this means that; x = y. I think the digital infrastructure art writing circulates within right now demands artists to often over-determine their work. There seems to be an air of mystery in yours still. It demands a lot of interpretation and seems open to different interpretations. Is that important to you to leave that room to allow multiple readings? Do you think that working as a collective with multiple voices allows the work to have the possibility of pluralistic interpretations? Like for example the guys from Chemion Glasses

MD: Every work we make is agreed upon in the group unanimously. Sometimes it’s really easy but most of the time it takes a lot of negotiation and conversation. At one point, we used to joke about enforcing the “rule of the conch” in order to keep each other in line when we would talk out of order. We make constructive compromises when we trust someone else’s decision. Let’s say one person isn’t on board 100%, but there’s still a trust and an interest in someone else’s thought process to let the idea pass — the work ends up being more open because of that.

Miami-Dutch, Ghost Bag (detail), 2015, Aqua resin, fberglass, fowers, 40.5 x 14.5 x 9 inches (102.87 x 36.83 x 22.86 cm), Unique

Miami-Dutch, Trough, 2015, Stainless steel, beeswax, paraffn wax, oak, fowers, fsh bone, paper,

earrings, shoelace, 18.75 x 48 x 15 inches (47.63 x 121.92 x 38.10 cm), Unique

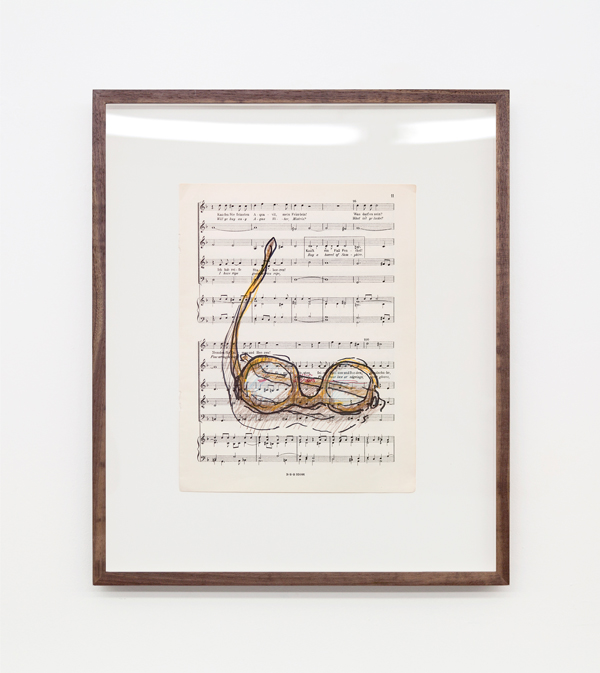

Miami-Dutch, London Street Cries (Train), 2015, ink and color pencil on sheet music, 12 x 9 inches (30.48 x 22.86 cm)

19 x 16 inches (48.26 x 40.64 cm) (framed), Unique

Miami-Dutch, Ghost Bag, 2015, Aqua resin, fberglass, fowers, 40.5 x 14.5 x 9 inches (102.87 x 36.83 x 22.86 cm), Unique

Miami-Dutch, London Street Cries (Portrait), 2015, ink and color pencil on sheet music, 12 x 9 inches (30.48 x 22.86 cm)

19 x 16 inches (48.26 x 40.64 cm) (framed), Unique

Miami-Dutch, Untitled (detail), 2015, Newspaper pulp, abaca fber, abaca pulp, spray paint, 40 x 59 x .5 inches (101.60 x 149.86 x 1.27 cm), Unique