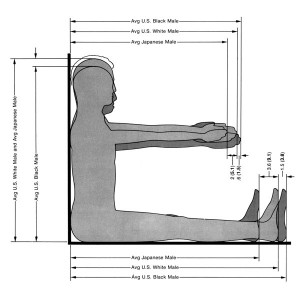

Lafayette Anticipation associate curator Anna Colin talks to artist Tyler Coburn about Ergonomic Futures, a speculative project engaged with art, design, science, anthropology and writing. In this interview, Coburn discusses the research, production process and network of collaborators of a multilayered project ultimately concerned with the futures of humankind. Anna Colin: When one comes across your museum seats Ergonomic Futures (2016—) in contemporary art exhibitions—and soon in natural history, fine art, and anthropology museums—they look… [read more »]

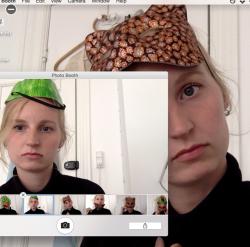

Maja Cule | Facing the Same Direction

Introductory notes by curator Cadence Kinsey from a conversation that happened on Saturday 11th October at Arcadia Missa Gallery, London at the opening of Maja Cule’s Facing the Same Direction.

I thought I would begin not by giving an introduction to Maja’s work but to say something brief about one aspect of my own research, with the hope that it might offer some context for this conversation, and why it made sense for us to work together with Arcadia Missa on this exhibition.

Much of my work relies on unpacking received narratives and mythologies around the Web, and digital technology more broadly. For example, I have looked at the emergence of the historical construction of the digital as immaterial or ‘abstract’, by considering how it was constituted in the intersecting discourses of postmodernism, finance and genomics. Sometimes, this kind of work reveals deeply conflicting discursive narratives, and this is the case when one looks at the origins of ideas around collaboration, co-creation, and participation (and each of these is highly particular in its scope and historical significance). Participation, for example, has represented competing, but parallel, ideological positions. On the one hand participation has been conceived in terms of the decentralisation and democratisation of information sharing (an idea generally covered by the term ‘networked publics’) but, on the other, it has also been thought about in relation to histories of work transfer. Historically, ‘work transfer’ has referred to the problems of automation and de-skilling but, more recently, has also come to be associated with the removal of paid labour, as characterised by the terms ‘prosumer’ or ‘playbour’, which refer not only to the production or sharing of content within applications or websites (commenting, reviewing, uploading) but also with more basic actions associated with the use of them (clicking, sharing, liking, following).

Thus, there emerges an unresolved tension in the discourses of participation, which we may characterise as being between commercial optimisation and an Open Source ethics. That the notion of participation remains ambiguous in relation to Web cultures and economies is, of course, vital to sustaining its commercial bite: Do What You Love (DWYL) is so oppressive because it knows that if you love what you do, you are likely to do far too much of it, and for increasingly little reward. This we know from looking, for example, at the emergent working cultures of the New Economy of the late 1990s, particularly the tech and start-up industries, where work became more and more like play. More broadly, this is now expertly captured by social media: leisure time can be colonised, and capitalised upon, simply because it does not appear as work. But there is also a striking relationship between DWYL and both art and academia, since, as forms of supposedly unalienated labour, there is a historical distinction between these kinds of activities and ‘work’.

This tension in the discourses of participation produces a series of ambiguities that are very interesting to consider, particularly in the context of recent art. Although much of this conversation was articulated at the end of the 1990s, it has only been in the last five years or so that this has entered the discourses of art in a significant way as a sustained enquiry into ideas around labour in the Web economy. Much of this work has been allied to the critical tradition of Italian Autonomist Marxism and has contributed to new understandings of the ways in which participation has been monetised. Arcadia_Missa have been important in formalising some of this through their programme of exhibitions, events and publications. My particular interest has been in practices that explore an ambiguous relationship to these structures, and do not simply make work about the digital economy. In so doing, they come close to dealing with the various forms of complicity that we engage in in our everyday experiences with the Web, instead of maintaining irrefutable positions of critical distance.

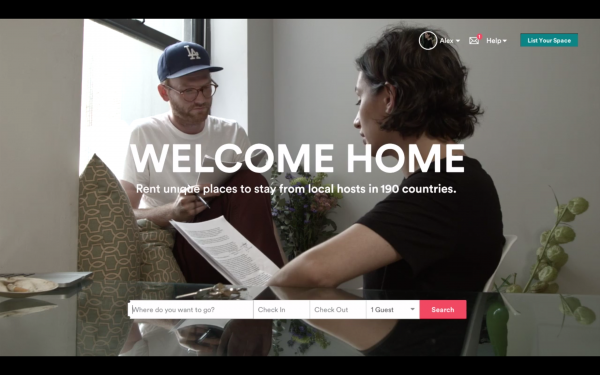

What I have found compelling is the idea that artists are a part of, not apart from, the kinds of economies that they are exploring. Participation in these cultures and economies can figure in many different ways, and one of the things I have tried to consider in the first chapter of my book is the various forms that this may take. For example, when I met with Maja at the beginning of the summer, we spoke a little about Airbnb. I had just arrived in New York the night before and was having some trouble with my hosts (they had assumed I was out, enjoying the city, and so were up most of the night, playing music, as they prepared their costumes for the Coney Island Mermaid Parade). Airbnb had also just launched an advertising campaign on the subway reading ‘New Yorker’s Agree: Airbnb is great for New York City’. In talking about the particular significance of Airbnb for New York, Maja happened to mention just how important this facility had been for artists, including herself at times, in providing them with an income that could sustain their practice without the usual obligations on one’s being in certain places at certain times, as per the 9-to-5 model. Thus, it became evident that it would be impossible to think the ‘sharing economy’ simply as a thematic within recent art, but that it needed to be taken seriously as a structuring condition of arts production more generally. This immediately generates a high-stakes field of enquiry, which requires the reassessing of some of our most basic assumptions about the category of art, such as the question of its autonomy.

It is this relationship between the work and the conditions of its production which has become increasingly of interest to me in so far as it puts a different spin on the notion of participation. This is also something that is fundamental to Maja’s wider practice. Elsewhere – such as in her film about Madame Tussauds, shown at Arcadia_MIssa in 2013 as part of a duo solo show with Dora Budor – she has looked at conditions of production, grappled with the technological capabilities of representation, and pushed against the edges and limits of image-making. Thus, the plan for this conversation [between the curator and the artist] is to draw out some of these ideas in relation to the show currently on view here, asking how the ideologies of the Web economy correspond to artistic production, what might remain of not working as a site of resistance, and unpack the problem of participation through the notion of doing what you love and loving what you do…

Cadence Kinsey is a British Academy Postdoctoral Fellow in the History of Art Department at University College London. She is currently working on a book project related to art after the Internet, which will be completed in 2016.

Facing the Same Direction

Arcadia Missa

Unit 6

Bellenden Road Business Center

London SE15 4RF

Exhibition runs October 12 – November 15

With: Anna Khachiyan as Alex, Justin Warsh as Man With the Microphone, Alex Hunter as Friend, Jose De Leon as Man With the Camera / Cinematography: Miona Bogovic, Tyler Sayles was the Script Editor, Video editing: Meriem Bennani. Thanks to Rozsa Zita Farkas and Tom Clark (Arcadia Missa), Cadence Kinsey and Silvija Stipanov.