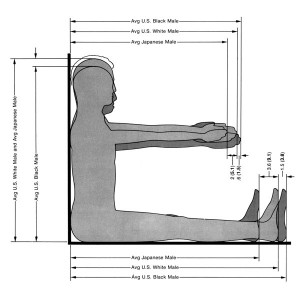

Lafayette Anticipation associate curator Anna Colin talks to artist Tyler Coburn about Ergonomic Futures, a speculative project engaged with art, design, science, anthropology and writing. In this interview, Coburn discusses the research, production process and network of collaborators of a multilayered project ultimately concerned with the futures of humankind. Anna Colin: When one comes across your museum seats Ergonomic Futures (2016—) in contemporary art exhibitions—and soon in natural history, fine art, and anthropology museums—they look… [read more »]

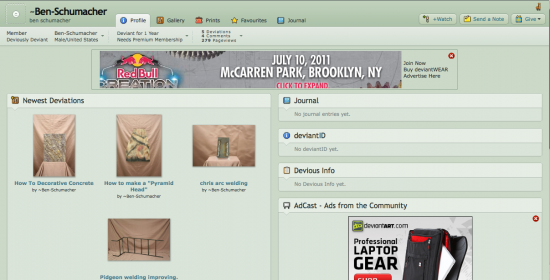

Screens on Screens | Ben Schumacher

The story about the liquid added to public pools that turns urine into an obvious blue color –mapping the perpetrator’s bodily fluids as far as they drift– is actually an urban myth used to deter people from the thought of peeing in pools. It is, however, a decent way to begin thinking about Ben Schumacher’s art. The drift of images and objects through the internet is a process silently contested, and many of Schumacher’s projects aim to destabilize or re-identify the seemingly normalized flow of digital information as it takes place in social networks. Schumacher has likened his efforts to re-acquaint the online audience with their viewing context in a way parallel to Brancusi’s interest in bringing attention to the pedestals on which his sculptures sat. For an artist whose practice tends toward the disclosure of unforeseen linkages, this historical referent is definitely fitting.

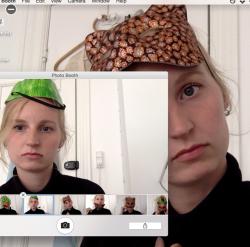

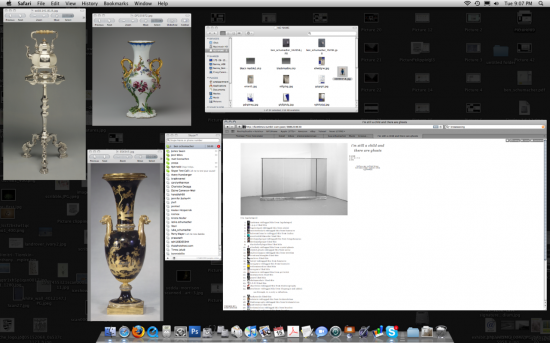

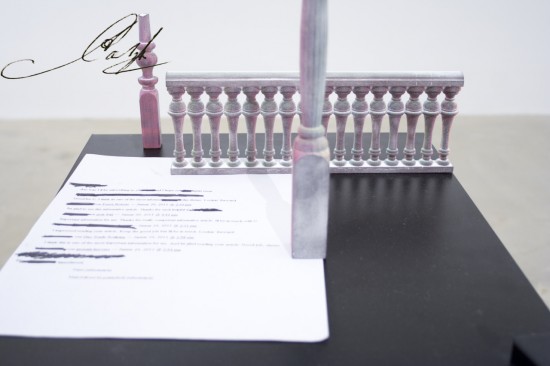

Embracing the altered nature of installation images when placed on his blog, Schumacher often overlays Photoshopped brushstrokes and signatures on his imagery; a gesture at once recognizing the object-turned-image’s new status as a flattened visual form while also self-effacingly acknowledging the transience of authorship in the images’ new digital environment. The sentiment forms that there are a number of people being attributed authorship to his work, an act that is perhaps pre-empting the many contexts a single image may be viewed through once part of the labyrinth of Tumblrs and image aggregates that exist. In a related project, Schumacher tracks the way people disperse his imagery through their own blogs, but here too the context Schumacher is interested in is multiple as well. In these screen grabbed images of his work being posted on other blogs, the artist includes a full view of his own desktop, revealing a new cast of browser tabs, installed software icons and desktop files each time. This twice-removed view of Schumacher coming to terms with his own work is offered up for further transcription and re-blogging on Tumblr, again revealing a willingness to absolve himself as the known creator and an interest in re-couping what happens when he does so. To this point, it should make sense that the artist has no collection of work online that is not a Blogspot or Tumblr archive, using only active platforms with built-in features for appropriation. Schumacher has even dabbled in posting his work on little known image hosting websites, noting the results as each of the companies slowly go bankrupt or are swallowed by larger companies.

They say if you love something you should set it free, and if it loves you back it will return: enter Schumacher’s work with the trading sites eBay and Craigslist. For his 2010 JstChillin project the artist openly propositioned 3D modelers on Craigslist to digitally replicate installation images of his sculptures. To his surprise, a number of modelers returned his query with modeled designs for free. Some responses were stamped with watermarks and messages from their creators urging Schumacher to pay them to receive the watermark-free version of their 3D modeled image. Schumacher obliged, maintaining an archive of his own installation images, the free versions offered by Craigslist modelers, the watermarked versions and the un-watermarked versions given after payment. The result is a body of images that both seamlessly blend and bluntly differ in appearance, highlighting (in some instances) the possibility for flawless digital simulation and in others the unsettled artifacts of labor negotiations. As Schumacher has said about textual scholars, “What becomes apparent through the reading of printed variants of the original file is not only differences in the modes of production but the subjective behaviour of the authors of the variants who will the original file into existence.” Names like Luna, Christopher Perez, and Belartist appear prominently as fingerprints left by red-blooded creators at the helm of technology indifferently geared towards leveling all difference in digital versus real comparisons. It is a quiet, though conceptually effective gesture that Schumacher always returns his compensated 3D models to Google Warehouse, an offering made as repayment at the altar of digital collaboration.

For his work on eBay, Schumacher has taken to sending car door windows at random, straight from the online marketplace, to unsuspecting individuals who have done studio visits with him. Without mention of whom the object is from or why they have received it, recipients often take a cell phone image of the object and message it to Schumacher and others in their phone book searching for the window’s sender. In an eloquent reversal of the aforementioned Craigslist’s works’ driving force being the negotiation of labor metted through censorial names, here the lack of an authorial signature actually propels the dispersion of images sent through mobile phones. Schumacher collects these cell phone images, along with the installation views offered on eBay and 3-D models he’s had his most trusted Craigslist workers create of the car door windows to form a layered viewing of an as-of-yet-virtual object Schumacher himself has never seen in person.

Similarly, the artist credits an interest in the mythical notion of Acheiropoieta –the idea of an icon not made by the human hand, such as the Veil of Veronica or the Shroud of Turin– as being a motivating force behind his use of 3D printing as a sculptural process and material. Schumacher says:

Scanning software used to map large areas of terrain enters the world simultaneously with the time of their production and denies any notion of subject or subjective gaze. The formerly irreducible time between an event and it’s inscription in the world is reduced to 0 and the subject (of enunciation and operation) has disappeared … Like Acheiropoieta, there now exists representation that functions autonomously, independent of human intervention and inscription.

Ironically the 3D printing technology Schumacher employs cannot help but manifest its own ‘fingerprint’ on its products. The green to purple tie-dyed color apparent on these Google 3D Warehouse-sourced objects is not the result of a gothic-hippie taste of Schumacher’s own, but of a breakdown in communication between the printers’ input and output. Due to the additive coloring process currently used by 3D printers (layering levels of cyan, magenta and yellow atop one another) black is a color unable to be printed by the machines, despite the information Schumacher includes in his files commanding the objects to be colored so. The resulting green to purple mist on the objects’ surface is, by design standards, a failure, though by artistic standards reveals a compelling glance at the medium’s inability to not interfere with the message. Or, as Schumacher says, “a digital model produced and printed in 2009 can have the exact same form as the same file printed in 2050; however, the physical objects themselves may differ in their material qualities and precision due to constantly updated printing technologies.” The notion of signatures (consciously made or otherwise) is never far off in Schumacher’s work.

Just as 3D prints are essentially objects representing virtual images (a reversal of our traditional understandings of representation relative to materiality), so too do Schumacher’s paintings strive to switch our perceptions of viewing order. A close look at his canvases shows a rugged cement base with enamel drizzled over at an extreme angle, as though dust had accumulated on them for centuries in a world of oblique gravity. From a distance this aging process reverses and the canvases’ abstract subject matter appears in hyper-contemporary style, identical to any number of the Photoshop-produced and Chinese-printed digital paintings that have become so popular recently. Like the simultaneously failed and generative surface of his 3D prints, Schumacher’s paintings use materiality to gesture towards an idealized future of representation. The ancient grit of cement appears to be a suitable form for seemingly ‘digital’ graphics, until the viewer steps too far to the right, left or approaches it too closely– then the facade crumbles under material limitation.

Perhaps in Schumacher we have found a truly Post-Internet artist, actively blending virtual and material information through transfer and documentation. Leaping from physical appearance to digital representation, known authorship to anonymity, or technological objectivity to the human hand, Schumacher’s art achieves interconnectivity in a way that transcends the rhetoric of a word used all too often.

Brad Troemel is a professor and graduate student at New York University. He writes about and creates art projects on the internet.