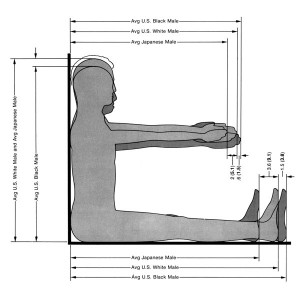

Lafayette Anticipation associate curator Anna Colin talks to artist Tyler Coburn about Ergonomic Futures, a speculative project engaged with art, design, science, anthropology and writing. In this interview, Coburn discusses the research, production process and network of collaborators of a multilayered project ultimately concerned with the futures of humankind. Anna Colin: When one comes across your museum seats Ergonomic Futures (2016—) in contemporary art exhibitions—and soon in natural history, fine art, and anthropology museums—they look… [read more »]

Deanna Havas on Cynicism, Ideology and the Golden Age of the Advertorial

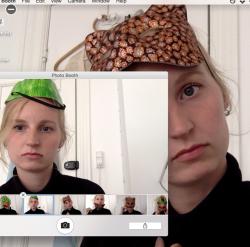

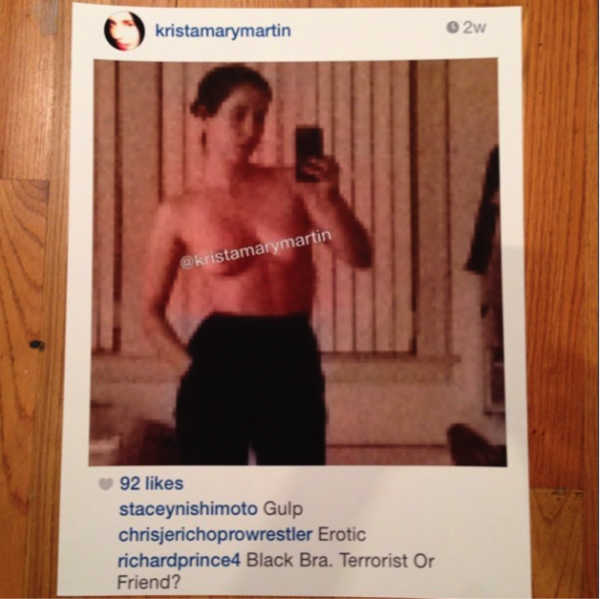

By now, many have seen artist Richard Prince’s attempt to integrate the #regram into his repertoire of sex, art and appropriation. In a bizarre series of Instagram portraits, Prince reappropriated, printed out, then photographed screenshots of Instagram photos featuring subjects ranging from Pamela Anderson to Junglepussy, often adding strange and sexually ambiguous commentary. All but five of the Instagrams have recently been taken offline by Prince.

As an expansion of her initial tweet, DIS Skyped-in with Harlem-based artist and poet Deanna Havas to get her 140-characters-plus take on cynicism, ideology and lifestyle branding in the golden age of the advertorial.

Anna Soldner: What did you think when you first saw Richard Prince’s series of Instagrams?

Deanna Havas: My friend texted me a screenshot of one of the photos. I checked out the feed and saw all these people that you and I know being repurposed. I was like, ‘oh, that’s so-and-so.’

Screenshot of Richard Prince’s Instagram. With the exception of five, all portraits have now been taken offline by Prince.

AS: I wonder if he has a studio assistant helping him search the Internet.

DH: I wouldn’t be surprised if there’s like, a power social media user behind the project. I’m not really sure. Maybe it was a coincidence.

AS: What do you find interesting—if anything—about it?

DH: On the Internet we presume an autonomous end user. The fictionalized aspect and photographic style reminded me of mid-2000s era advertorials. They came about in a very cynical and ambiguous time and context.

AS: The advertorial of 2014—is it different than the advertorial of the mid 2000s?

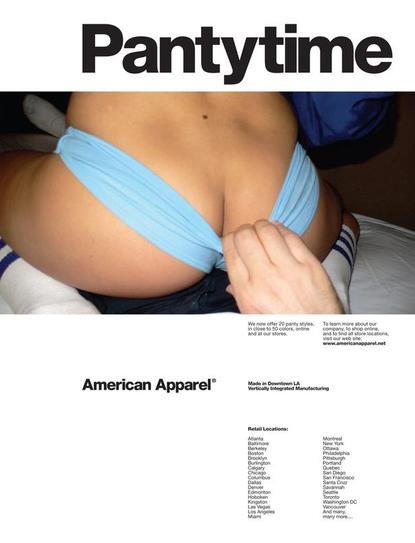

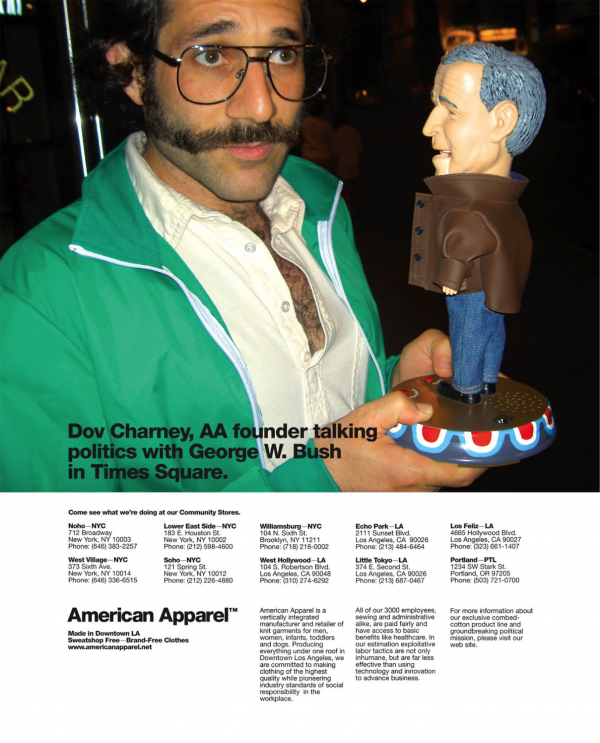

DH: Look at American Apparel ads from 2003 and compare them to ones in 2014 and they look more or less the same. There’s totally a pimp network of male photographers that cycle through a lot of the same people leftover from the mid-2000s era. It’s interesting that this type of art is still being made; there’s a definite longing for a different time that maybe wasn’t there.

2013 JTOne lingerie campaign shot by LA-based cult party photographer Mark Hunter aka ‘The Cobrasnake’.

Once broadly celebrated by the fashion community, photographer Terry Richardson is now vehemently rejected by many—especially young, culturally engaged people who view his work as tasteless and predatory.

In a recent cover story, Richardson, 48, told NY Magazine he denies the countless allegations of sexually harassing models during photo shoots: “I don’t have any regrets about the work at all,” he said.

A drunk and incapacitated woman photographed by Merlin Bronques, pioneer of nightlife party photography and founder of lastnightsparty.com. ©2006

AS: How would you characterize the cynicism of the previous decade?

DH: You can think back to Vice and Terry Richardson during that period; it was sexualized, voyeuristic, very ambiguous and kind of misogynist.

During that time you had Enron, the Abu Ghraib [prisoner abuse] scandal and the unitary executive stuff with Bush. I think the Iraq war felt pretty inevitable and that had a cascading effect on the cycle of oppression. With the context of so much violence and a whole bunch of things that led to that political climate, you’re left feeling really powerless and cynical.

A female prisoner in Abu Ghraib showing her breasts in a photograph taken by Cpl. Charles Graner, on October 29, 2003. During the Iraq War, United States Army military personnel physically and sexually abused, tortured, raped, sodomized, and killed prisoners.

The advertorial was fostered by that as a form because there’s the inevitability that, at the end of the day, even editorial work is serving a brand or the collective interest of the advertisers in a given publication. When you think back to what was going on during that time, you can see how that feeds into the entire machine.

AS: Has the zeitgeist evolved since then?

DH: Today, when we see or talk about the female form on the Internet, we have this socially just culture that is critical of that rather than being complacent with it. I think now, in contrast to the past decade, women are really trying to reclaim their bodies.

AS: Is the #freethenipple campaign something you see leading to good, constructive outcomes?

DH: It will totally blow over and we will be raving about a new body part tomorrow.

AS: Is there power in the selfie?

DH: There have been some violent incidents regarding selfies in the media in the past year, even leading to bloodshed. It apparently has sociological consequences so we need to be careful with this form.

The now-deleted Prince #regram of LA-based artist Krista Mary Martin, printed out and captioned: “Black Bra. Terrorist or Friend?”

AS: Do you identify as a feminist?

DH: I can’t say that I’m not a feminist, that’s just incorrect to say. But do I think that I’m a good feminist? Maybe not always. Maybe I don’t contribute enough to the cause or do backward things or let the patriarchy get to me. I do my best. ♦