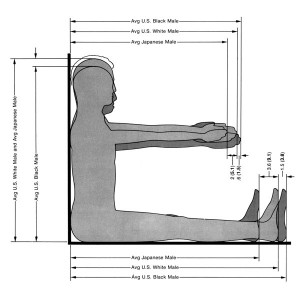

Lafayette Anticipation associate curator Anna Colin talks to artist Tyler Coburn about Ergonomic Futures, a speculative project engaged with art, design, science, anthropology and writing. In this interview, Coburn discusses the research, production process and network of collaborators of a multilayered project ultimately concerned with the futures of humankind. Anna Colin: When one comes across your museum seats Ergonomic Futures (2016—) in contemporary art exhibitions—and soon in natural history, fine art, and anthropology museums—they look… [read more »]

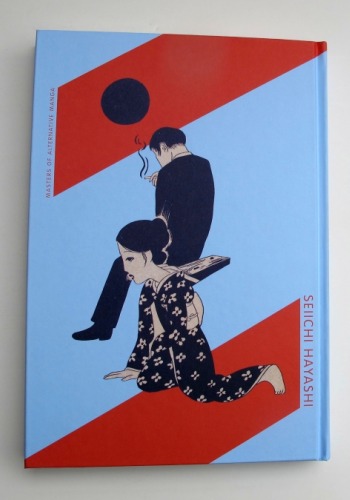

Manga Nouvelle Vague: Seiichi Hayashi’s Comics

If there was ever a moment when Japanese comics crossed over into art, it was with the work of Seiichi Hayashi in the late 60s and early 70s.

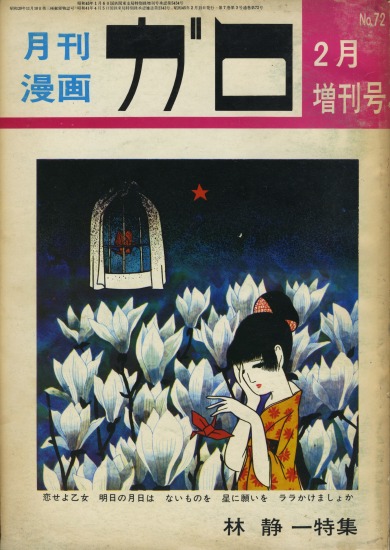

Hayashi’s name is indelibly associated with Garo, the legendary monthly comics magazine, which, in turn, is virtually synonymous with “alternative manga.” From the magazine’s founding in 1964 to its temporary demise in 1997, whether crafting new narrative forms, incorporating visual ideas from contemporary art and film, favoring fresh forms of graphic expression over conventional technical skills, striking to the existential core of young adulthood in developing Japan, or diving to the depths of vulgarity, Garo’s artists repeatedly redefined what it meant to make comics.

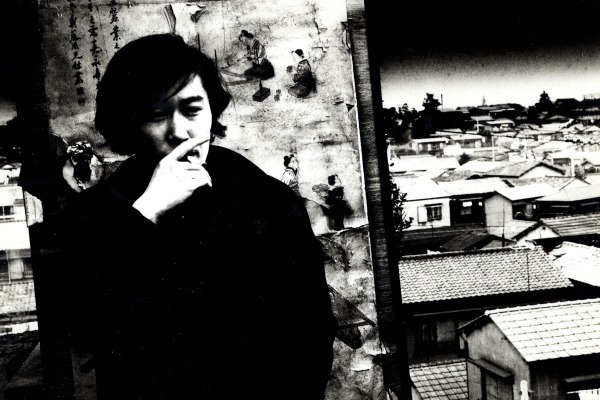

Debuting in the magazine’s November 1967 issue at the age of twenty-two, Hayashi was one of the first Garo artists to make experimentalism his monthly métier. Older artists like founder Sanpei Shirato (b. 1932), Shigeru Mizuki (b. 1922), and Yoshiharu Tsuge (b. 1937) had been publishing work in Garo that might not have been initially welcomed in mainstream venues. But their style was nonetheless firmly rooted in the graphic styles, storytelling techniques, and literary sources of an earlier moment—the mid to late fifties, when they themselves had emerged. Born in 1945 and thus by some years these other artists’ junior, Hayashi helped take Garo in new directions, both inward—with works engaging his personal life and the struggles of being a young artist—and outward—with an oeuvre that transcended comics and mixed with the wider world of Tokyo’s vibrant counterculture.

Hayashi’s activities in the late sixties and early seventies are paradigmatic of the crossing of artistic media typical of those years. His manga incorporate drawing styles and storytelling techniques derived from animation, traditional Japanese art, American comics, French and Japanese nouvelle vague film, yakuza movies, and popular music. The popularity of his Garo work brought him commissions for poster designs from underground theater troupes, set designs from experimental filmmakers, and cover designs for books, magazines, and music albums. His most famous manga, Red Colored Elegy (Sekishoku erejii, 1970–71), which tells the story of a young man and woman trying to keep their relationship together while juggling family problems and the pressure of working as freelance animators, inspired first a hit single in 1972 by folk singer Morio Agata before being turned into a film in 1974 by the same. Hayashi was not only a respected artist; he was also a small-time pop star.

Using know-how learned while working at Tōei Animation Studios from 1962 to 1965, Hayashi also made his own short animated films, screened at art-film festivals at home and in Europe. In 1973, he directed his first and only live-action film, Rubbing Our Cheeks Together in Dreams (Yume ni hohoyose), produced by the notorious Kōji Wakabayashi and screened at Sasori-za, the famous independent ATG theater. Near 1970, he started making drawings, prints, and paintings of impassioned shōjo and willowy bijinga (traditional beautiful women), collected in a handful of limited-edition books and exhibited in prominent Tokyo galleries in the early and mid seventies. His character designs and TV-commercial animation work for Lotte Koume (Little Plum) candy drops, which debuted in 1974, won numerous domestic and international prizes. His images of a young girl in kimono with puckered lips from the sourness remain on the candy’s packaging to this day.

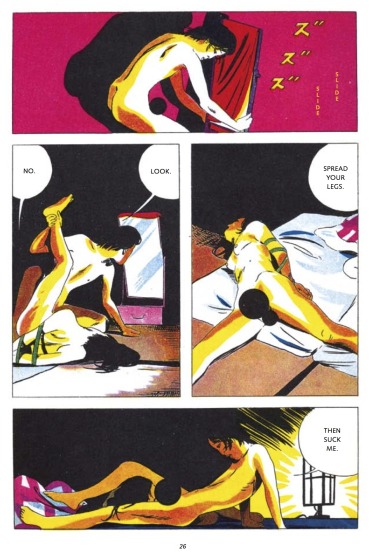

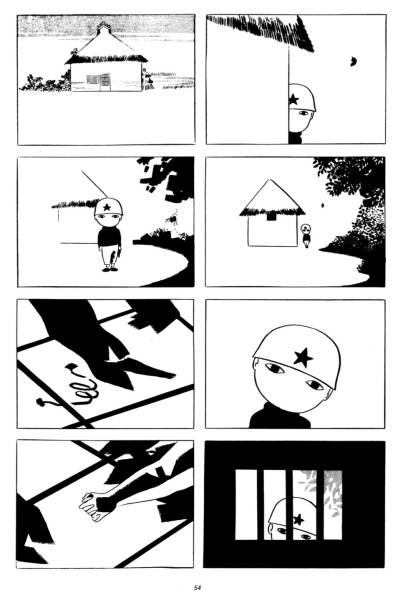

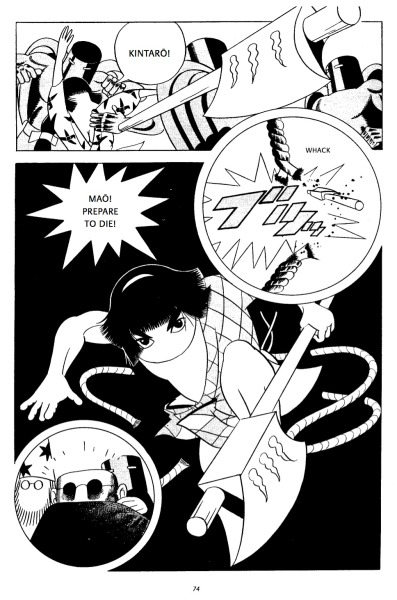

Hayashi’s design and film work is interesting, but his comics are one of a kind. The first publication of Hayashi’s work in English was Drawn & Quarterly’s edition of Red Colored Elegy in 2009. And now there is Gold Pollen and Other Stories from PictureBox in Brooklyn, which collects a number of Hayashi’s most famous manga from the late 60s and early 70s, including works that are widely considered masterpieces in the medium. For example, there is “Red Dragonfly” (1968), a short 12-page work that is almost always included in surveys of late 60s Japanese culture. Through images inspired by Japanese ink painting and children’s songs, it looks at the day in the life of a young boy whose father died in the war and whose mother is forced to quietly sell her body so that she and her son can eat.

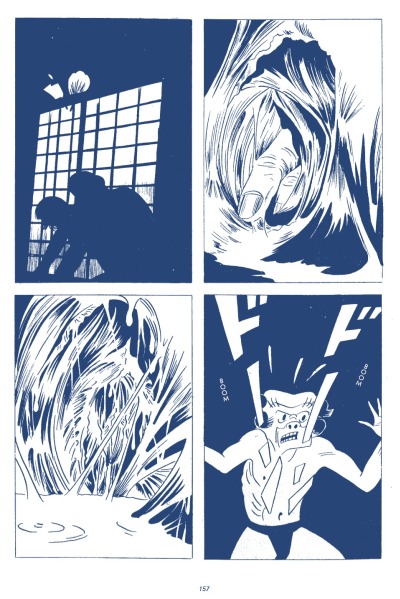

Also in Gold Pollen, “Yamanba Lullaby” (1968) should be recognized as an icon of Japanese Pop Art. It narrates the generational conflicts of the sixties through a mash-up of Edo period woodblock prints, American comics, French animation, and the era’s psychedelic art. Printed full-color, the fluorescent yellows and pinks of “Dwelling in Flowers” (1972) look like 80s New Wave ten years ahead of its time. Based on Hayashi’s own life, this is a wrenching story about a son struggling to live with a mother suffering from intense depression. The longest work in the anthology is “Gold Pollen” (1971). Personally I think it’s unfortunate that Hayashi began focusing his energies on design jobs in this period, because the graphics of “Gold Pollen” are really stunning, totally unique, a mix of Kandinsky and Taishō period illustration, with additional references to woodblock artists like Kuniyoshi and the pantheon of Buddhist deities. The sequence in which the hero claws his way out of the maternal womb should not be missed.

As editor and translator of the book, one of my hopes is that the strength of Gold Pollen will help force down the walls that continue to divide art and comics. In the case of Japan specifically, a country in which comics have been one of, if not the definitive visual medium since the 1960s, shunning manga really makes no sense. In addition to the comics, Gold Pollen also includes an English translation of an autobiographical essay Hayashi wrote in 1972 and an introductory essay by me. I hope this book does justice to Hayashi’s work, which really deserves to be part of the canon of world’s contemporary art. PictureBox and I did our best to give Hayashi a red carpet treatment.

You can buy Gold Pollen at the PictureBox website by clicking here