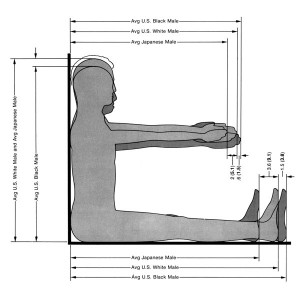

Lafayette Anticipation associate curator Anna Colin talks to artist Tyler Coburn about Ergonomic Futures, a speculative project engaged with art, design, science, anthropology and writing. In this interview, Coburn discusses the research, production process and network of collaborators of a multilayered project ultimately concerned with the futures of humankind. Anna Colin: When one comes across your museum seats Ergonomic Futures (2016—) in contemporary art exhibitions—and soon in natural history, fine art, and anthropology museums—they look… [read more »]

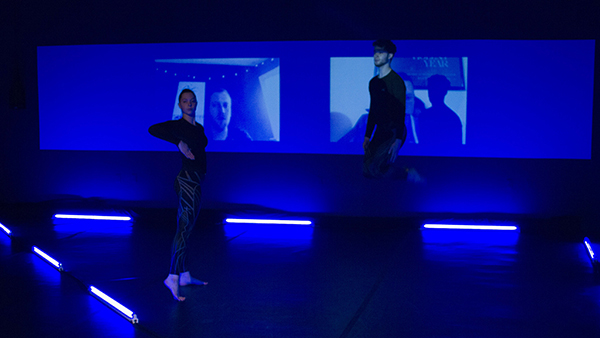

abduct | Xavier Cha

As a part of the commission programme for Frieze Film 2015 which will be screened at Frieze London and air on BBC’s national Channel 4, Xavier Cha presents abduct, a cinematic study of performative self-estrangement in the virtual age. Xavier Cha’s conceptually-driven practice spans dance, video, text and audio, but central to her work is the expanded field of performance. Since graduating from UCLA in 2004, she has shown live and video work across the US and Europe, including Kunsthalle Düsseldorf, the New Museum and the Whitney. Her works concern themselves with the ambiguity of human existence, “our mutating, uncomfortable, alienating and awkward relationship to our “selves,” she explains in the Exhibitor’s Lounge at Frieze London 2015, “and what it means to be or feel human after managing infinite and immortal virtual bodies.”

Xavier Cha was born in Los Angeles, but grew up in Dallas, Texas. An underlying interest in subjectivity developed at an early age, making her feel alienated whilst attending school. “I always in some way want to push the boundaries of my humanity,” she explains. “I have never been able to relate to people who accept an ordinary/routine path.” In her own early self-imagined artistry, she drew images of herself in a bikini, holding a palette and standing at an easel on the beach.

‘Acting’ as a formal, object-like phenomenon crystallizes in much of Cha’s video work, in which the viewer is asked to reflect on the medium-specificity of film and the role of performance in it. Acting manipulates space and time in any context, and Cha tests the boundaries of these manipulative strategies (that are also inherent in mainstream media) by amplifying its borderline manifestations. Her 2011 piece Body Drama captured the anxious response of actors as they were linked to body-mounted cameras, inescapable from their gaze; inversely, her 2012 solo show at 47 Canal Street filmed subjects experiencing an induced meditative transcendence, removing their sense of “self’ and ability to control their image on the screen.

In her new film, the self seems to have been co-opted and led to a performative extreme within the apparatus of film. The still, hypnotic presence of the diverse cast evokes the mesmerizing test shots of Andy Warhol, but while Pop tried to charter a time-based presence of selfhood within the moving-image medium, Cha discusses its social and affective implications. Standing in a brightly-lit photo studio, the actors elastically work their ways through a double-range of non-verbal emotional registers, which range from ‘shocked sorrow,’ to ‘ecstatic cerebral pleasure’ and ‘apologetic laughter,’ or ‘inhibited sadness’. The generic uniqueness of these expressions resembles the hollow hyper-specificity of stock photography, and suggests how media produces a level of self-estrangement in its self-reflection. Xavier had begun conceiving the idea for the film for her upcoming solo show at MOCA Cleveland, and only received the Frieze commission later. She put up a standard casting call and held two days of auditions by appointment, looking for a large age range and ambiguous racial profiles. The strict lack of dialogue was a challenge to many, and she quickly spotted those who were able to perform the amplified expressionism she was looking for. “It’s strange with physical acting – it’s something that became very obvious, some people really need lines, or they don’t know how to act,” she says.

Body Drama, 2011, Performance with body-mounted camera; HD video projection, Whitney Museum of American Art

Xavier’s concern for physicality transcends the digital, but “is absolutely informed and carried by digital experience.” “I’m more interested in our morphing and evolving struggle with subjectivity versus delusions of agency or autonomy within these inescapable structures of digital/information capitalism. I’m interested in how all of this is changing our physicality, our subconscious and psychic dimensions,” she says. Particularly the amplified opticality of these information structures brings up questions about self-spectatorship, surveillance and voyeurism – and how these distinct relationships of gazes collapse under the omnipresence of technology. “You feel alienated from the physical expression of emotions after having your life so seamlessly and flawlessly extended into the virtual, behind which vulnerabilities are easily masked” she explains. “When you have to feel the physicality of expression, it can feel so alien.”

In conjunction with her art practice, Xavier is a routined Pilates instructor with a fully-functional operation in New York, which from an outsider’s perspective seems like an organic extension of her creative work: bodily and emotional flexibility, breathing, self-improvement and most importantly, the presence of machinery in this process, as a sort of as she puts it, Cronenbergian melding of body and technology. “Physicality and my relationship to the boundaries of my human body is always on my mind,” she admits despite never having concretely linked the two practices, “you really have to connect to the Pilates equipment to feel the work. I am interested in how the presence of machines, the camera lens, the monitoring of our navigation paths, etc affect and change the way we behave, think, move, and feel in our faces and bodies.”

Body Drama, 2011, Performance with body-mounted camera; HD video projection, Whitney Museum of American Art

Cinema as constructed context is internalized in abduct, as we see the actors jumping in and out of character while fragments of the studio space are continuously revealed. It exposes the deceptive nature of the cinematic medium, as the unorthodox rhythms of emotional manipulation fail to gratify – without an emotional arch that is logical, the absurdity and violence of performance crystallizes. “Like when you look at the girls (or guys),” Xavier reflects: “you think, ‘she’s hot’ and then she does something really weird, denying you of that desire.”

The Frieze commission triggered Xavier to approach the filmic medium more playfully than before, looking closer at the narrative and aesthetic devices that constitute the visual consumption of emotion. As the title suggests, the film places itself within a futuristic sci-fi cinematic tradition – the excessively moisturized models are presented in a brightly-illuminated, white photo studio, captured in a super-stylized format (exaggerated panning, awkward zooms) simulating the apparatus of the commercial fashion video and the horror-film all at once. In abduct, the formalisation of mass-cultural subjectivity is achieved, finalized and sublimated.