Lafayette Anticipation associate curator Anna Colin talks to artist Tyler Coburn about Ergonomic Futures, a speculative project engaged with art, design, science, anthropology and writing. In this interview, Coburn discusses the research, production process and network of collaborators of a multilayered project ultimately concerned with the futures of humankind. Anna Colin: When one comes across your museum seats Ergonomic Futures (2016—) in contemporary art exhibitions—and soon in natural history, fine art, and anthropology museums—they look… [read more »]

How to Sleep Faster #6: Sex

Amalia Ulman.

The 6th issue of How to Sleep Faster, the critical theory/poetry journal published by Arcadia Missa, continues HTSF’s investigation into contemporary sociopolitical and philosophical issues through the prisms of feminism, queer theory and Marxist critique. For this issue HTSF attempts to grapple with the most intimate of all subjects: sex. As a response to the mainstreaming of much identity-political discourse on sex (#heforshe, Everyday Sexism, No More Page Three, to mention a few), ‘the act of fucking’ is tackled in various formats and from various angles: poetry, history, politics, labour, aesthetics, protest and reflections on everyday life. As its editorial note expresses, the issue explores “sex that has formed us for better and worse; (…) the sex we still have not done, but wish to imagine.” What has motivated this group of contributors, ranging from historians, artists, poets and composers, to write or make art about sex today? What can we learn from the sexual?

Below are a series of excerpts, as well as comments made by some of the many individuals who took part in the creating of How to Sleep Faster 6.

Penny Goring.

Brooke Palmieri is a London-based historian specializing in 17th century England, its ideas and mythologies and radical communities. In her essay Sex & Alchemy she problematizes the conceptualization of historical sex, that is to say the archeological investigation into sex of the past. How was sex before capitalism, for example? Or sex without representative governance?

“It’s a pretty safe space to think about sex in, say, the seventeenth century. Sex that is 100% conceptual is 100% consensual, it stops when you get bored imagining how fucked up it all used to be for people 300 years ago.”

Focusing on the 17th century, Brooke carefully reviews historical sources of the time – like the 1680 book The School of Venus, or the ladies delight, which can vaguely be described as a sex guide written in the peculiar literary style of ’Whore Dialogues’, a historical form of erotica typically written by straight men in the form of liberal conversations between imagined female prostitutes. Rather than the truth, accounts of intercourse found in such performative literature should be read as intricate layers of mediations, narrations and representations, continuously redefined as the text travels through changing forms of owner- and censorship.

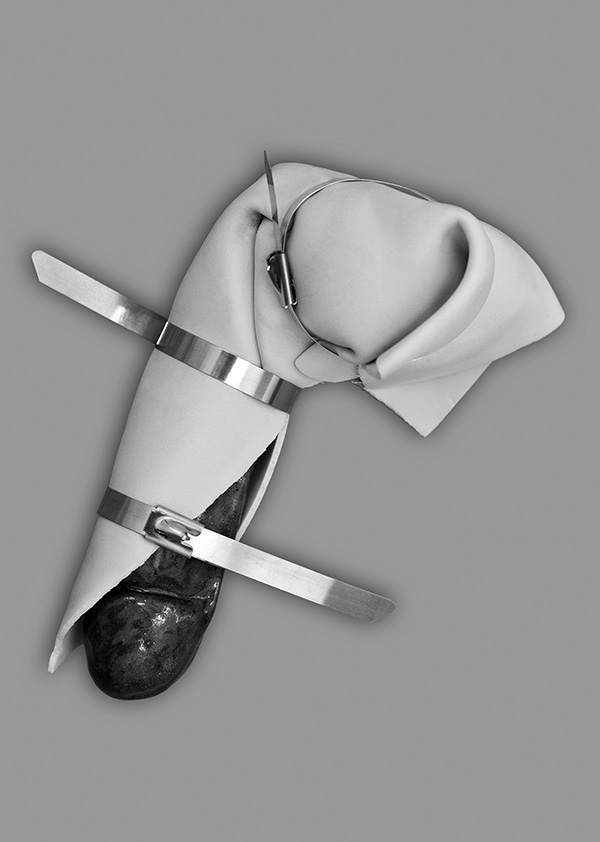

Adam Saad.

Jeppe Ugelvig: Why do you think it is important to discuss sex today?

Brooke Palmieri: I think sex is the ultimate moving target within embodied human experience, so there will never be a word or image precise enough to really pinpoint what happens during sex and what that will come to mean for the people involved. You’re always fucking in three tenses:, past, present, and future; you have your precedents, you have an immediate experience, and more murkily you have a future identity you’re aiming toward that this experience will come to populate. Like any transcendental experience it’s important to keep talking and producing documentation of it as a way to grapple with its shifting nature. My ideal would be to replace scripture with sex:, give it endless traditions of exegesis and commentaries on what it means, endless schisms and heresies that take on cults of their own. Excessive documentation and discussion of sex requires the realisation that it’s always changing. Which brings me to your second question:

JU: What about sex do you feel still requires urgent addressing, and in what way can sex be a scope for us to discuss current social, political or philosophical climates?

BP: I think that it’s important to distinguish the need to talk about sex from the need to legislate or discriminate based on it. A whole lot of ideas about sex over the centuries have hardened into rules that have harmed people. In this way there should be endless talking about sex to avoid getting too complacent with what has already been said.

HIS CORPORATE CUNT ART, Sidsel Meineche Hansen; Credit: Nikola Dechev.

My piece was about dredging up some historical representations of sex that show it to be just as elusive, fun and troubling for people to describe 300 years ago as it is now. Examining rare surviving historical representations of sex disrupts any kind of progress narratives we’ve come to appreciate about sex in society –there is no universal progress, only progress for some, depending on the time and place.

As Palmieri rightfully points out in her essay, talking about sex in the 17th century can only ever be a talk of its representation. However, the representation of sex, and particularly, sex’ image, is saturated with a multiplicity of symbols that tells us how we might think about, idealize, fear and (mis)use sex today. This is precisely the interest of British artist Ruth Angel Edwards, another contributor to HTSF, as she explains in an e-mail:

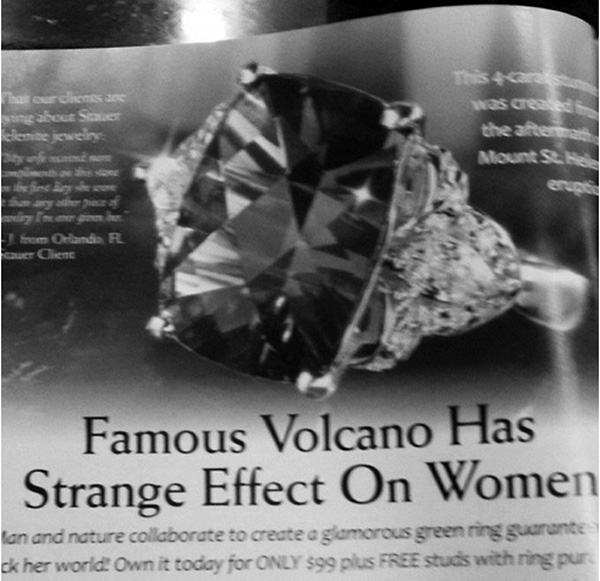

I’m interested in the way sex, or imagery that symbolises sex (in an established mainstream sense) has become a ubiquitous part of visual culture. It’s to me the most raw, exposed example of the way out desires are co-opted into and exploited by the machinery of late Capitalism. What interests me in particular is the way the same reproduced images and image ‘types’ are so prevalent that their proposed function as something actually sexual is undermined. We are almost immune. So what is left is a kind of gesture towards something which is in itself abstract. You could argue that images of women in this context are not actually ‘about’ women at all, or even about sex. This area is an obvious space for discussion, rebellion and subversion at this point in time. Sex is intrinsically linked to the language of consumerism and induced mass distraction through constant mild titillation. We need to invent a new language, exposing the power structures at play, imbuing existing images with new meaning and creating our own.

Amalia Ulman.

Sex’ presence in contemporary visual culture is undeniable, from advertising’s embrace of pornographic tropes to the the fetishistic overtones of much fashion. Ruth’s digital collage Pornstep sources its visual components from various music and video-sharing websites as it tries to decipher the phenomenon Pornstep; “a form of Dupstep so filthy and whorelike it’s part of a whole new sub-genre.” Real and animated fetishistic images of supposedly lustful women are superimposed with track titles like “D’n’B/Dubstep Rape Mix” and “special dedications to a Bitch” – reminding us that pornographic appropriations most often advances to straight up misogyny and/or female violence.

In her work No Right Way 2 Cum (2015), Danish artist Sidsel Meineche Hansen breaks the recent ban of female ejaculation in UK produced pornography– by extending it to the virtually immersive. Through the use of Oculus Rift, Hansen captures the 3D model ‘Eva v.3.0’ in a female-ejaculation scene in a CGI format. Her piece was shown at Temporary Gallery in Cologne and Künsthatlerhaus Bremen earlier this year, and confronts the viewer with the reminder that even in the virtual, which once promised utopian abstraction from the hegemonies and normativities of real life, sex (when commercialised) is maintained in a gendered, binary representation. Nonetheless, the piece is distinctively sex-positivist with regards to ‘female’ sexuality – and will hopefully be disseminated eagerly as a virtual form of sex-activism vs mainstream 3D porn planforms like X Story Player. In an e-mail, Sidsel describes her approach to the project:

With the neo-liberalisation of feminism and queer happening, I firstly had to think about if and how I was complicit with this development. I pass as: European, white, female, (currently) heterosexual and able-bodied, and therefore I can only address queer politics theoretically in order not to appropriate queer identity. I think this question of appropriation and by extension – the question of how technology can be used to appropriate sex and gender – is important. Capitalism has always appropriated sex both for reproduction purposes and surplus value. But currently, under advanced capitalism both biological and (predominantly female) virtual bodies are accumulated through the gender binary, and I’m interested to know how the latter complicates identity politics.The female avatar, it seems, is becoming an incubator for patriarchal 3D sex and therefore a cyberfeminist analysis and exploration of sex in VR is important, I feel.

As How to Sleep Faster quickly establishes, sex is a site of political conflict – a site of violence and suppression, but also debate and protest. With the emergence of communication capitalism (read: commercial social media) co-opting the sexual affect we previously kept private sex becomes an even more pressing issue in contemporary critique of society.

… and we have realised we may have to backtrack, as we never began with the way that we may

be able to see our own sexuality as distinct from capital’s assembled mantra of ‘sexy’ – instead, we took certain freedoms to ‘have’ sex as meaning that sex was not a valid site for resistance. We think we were

wrong. For one, whilst sex is still used as a violence, it cannot ever be fully a freedom, which is why we must renegotiate the sex we are doing, and the terms we are doing it on. (Editorial note)

Specifically, due to sex’ constant and at the same time liberating and suppressing appropriation of already-established power and gender roles, sex is always-already political and must be deconstructed in relation to its actors, its motivations and its effect.

Aurorae Parker.

Rozsa Farkas’s essay on reproduction rights and patterns in the US and UK demonstrates how neoliberal capitalism haunts the sexual, as it does all aspects of our lives. Feminism, she argues, has wrongly been blamed to be the cause of stagnating birth rates since the ‘60s, while in fact such a development is more intricately entangled in the violent societal structures imposed by neo-liberal capitalism’s post-Fordist production systems. Discussing the writing of radical feminist thinker Shulamith Firestone and Foucault, she dissects the gendered labour of human re-production.

“If our technological development wasn’t harnessed by capitalism, to enable more women to produce children or not (we’re still waiting for the male pill to actually come – 2020 apparently), but rather, to produce children in situations not only outside of gender roles, but outside of sex itself, then maybe reproduction wouldn’t continue the gendering of labour, and thus be so tied to it.”

Once sex is considered within a labour/political paradigm, it can similarly become a weaponized form of agency, and even of protest:

”Non-reproduction is a refusal to recreate the apparatus of capital (which involves much unpaid labour). Sometimes non-reproduction involves not so much ‘no babies’, but a demand to not reproduce certain relations, rather than to simply stop making more people.”

In fact, even sex’ very negation – celibacy – has, if released from its association to conditioned life-praxises dictated by oppressive belief systems, the “potential to perform as as a political statement against a capitalist, repressive society.” In her contribution to the issue, Hatty Nestor explores the argument of celibacy as protest and as the ultimate declaration of sexual autonomy, targeting the misogynist overtones in the concept of ‘sexual freedom’.

Elsewhere in the issue, James La Marre, a poet and digital designer based in New York, reflects obsessively upon aquatic analogies of the body: water as symbol for the body’s fluidity. In an e-mail he explains his motivations for discussing ’the sexual’ today:

Since at least the beginning of an epistolary history, sex in mainstream, popular culture has largely been relegated to the technologies, which fuel the pursuit and eventual rendezvous of bodies in space. The use of these technologies has become more and more dangerous, however, as sex remains hierarchized along ideological, political, and party lines — nudes and dick pics leak more often than their corresponding body parts, and end up stored on more than just a fragment of paper. Foregrounding the act of bodies converging in space and time, sometimes within/around/through hierarchies, marginalized communities actively subvert or bloat passages in the pyramid, like water rushing through the sinking mecca of Atlantis.

ONE-Self, Sidsel Meineche Hansen, Temporary Gallery, Cologne; Photo: Simon Vogel, Cologne.

In his contribution to the issue, entitled Dammed Bodies, he recalls fragmented experiences and observations of the liquids of the human body in relation to its surrounding spatial infrastructures. “Can damming occur in the body?” he asks in the beginning of his text. Through time and experience, ‘the body’ is collected, distributed, rushed, replenished, modified, left stagnant, and dammed, just like the highly-structuralized water supplies it lives off.

Standing still, just for a moment, trying to anoint this moment with permanence, yet fluidity. Attempts to move, on, fast, but to cling all the while

These are my thoughts in a VIP booth at MiArt, using a bored look grazing over the other singular man in the area. Although now I look up and see he’s gone. Maybe he thought I was sketching him.

Anyway I don’t give a shit about that guy, just occupied by a feeling — I will go and look at more art and a desire to go back to the park and sleep there. It’s d odd though – I don’t feel safe here.

Does more than fifty percent of my water come from a single source? Does it go to a single source? Who aligned the tributary, pointing sometimes toward the moon — sometimes toward you, so much I have to drink water continuously all day or I start heaving, deserts forming at the dams, air passing over dry parts as water rushes anywhere else, anywhere but my heavily modified water body.

Sex, while problematic in many ways, continues to exist as a window to a utopian fantasies wherein we imagine new possibilities of social, political and physical (infra)structures – and perhaps, targeting its embedded problematics may lead to a better future.

Cristine Brache.