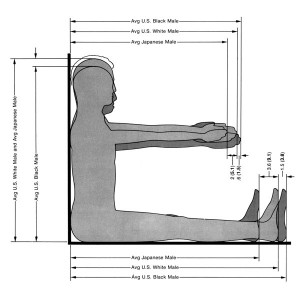

Lafayette Anticipation associate curator Anna Colin talks to artist Tyler Coburn about Ergonomic Futures, a speculative project engaged with art, design, science, anthropology and writing. In this interview, Coburn discusses the research, production process and network of collaborators of a multilayered project ultimately concerned with the futures of humankind. Anna Colin: When one comes across your museum seats Ergonomic Futures (2016—) in contemporary art exhibitions—and soon in natural history, fine art, and anthropology museums—they look… [read more »]

Pindul’s Rewards | Carlos Reyes and Alessandro Bava

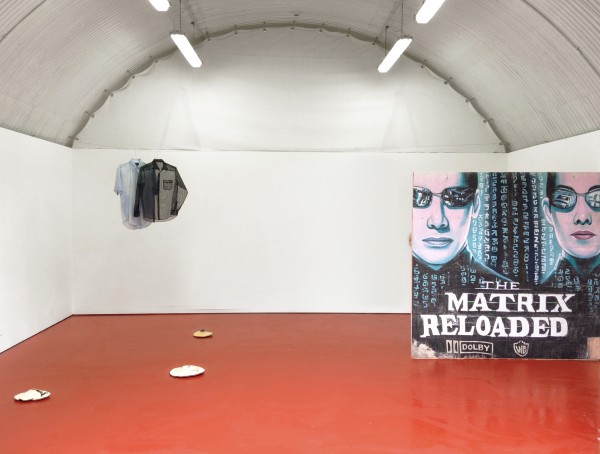

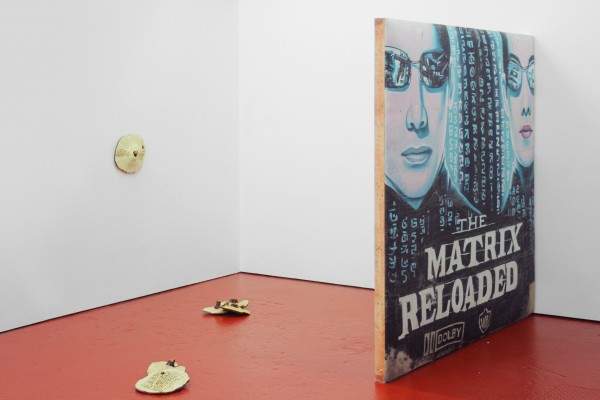

Carlos Reyes, Pindul’s Rewards, Installation view

Let’s, for a moment, argue that art and politics (as we currently practise their convergent theories, and – with a secondary disclaimer – specifically in western visual art terminologies) has its roots in Italy. We’ll point out how the artists’ manifesto was the first real example of the merging of art and politics in the form of the art object, and that it was The Founding and Manifesto of Futurism (published in Bologna in 1909) that provided the textual aesthetic template that would become common to all subsequent artists’ manifestos. Its introduction unpacks a narrative that forms the basis for the propositions that follow; its conclusion takes the form of a rhetorical speech act that defines or critiques these propositions. The artists’ manifesto proposes a new social ideal based on embedding the principles and morals of a movement’s perceived ‘ideal’ of art. The manifesto, after Futurism, became the most effective mode of criticism and rhetoric.

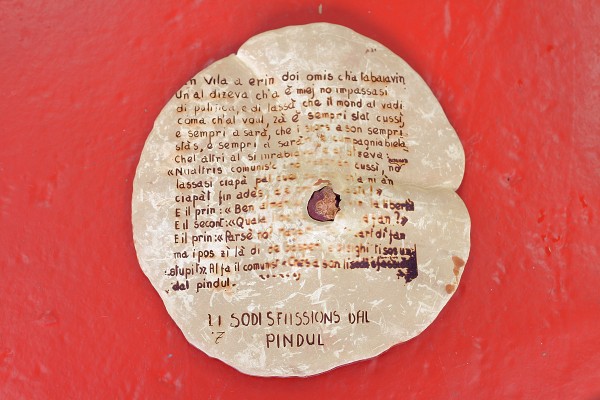

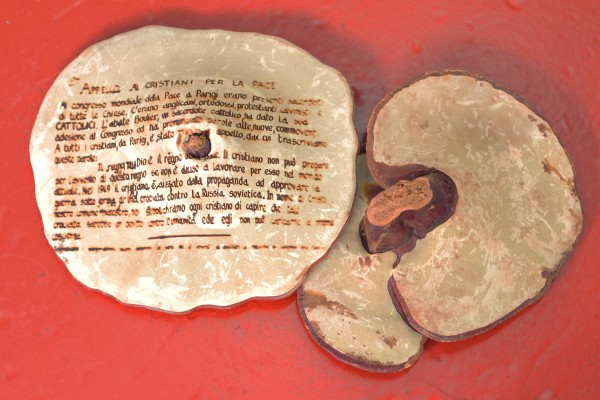

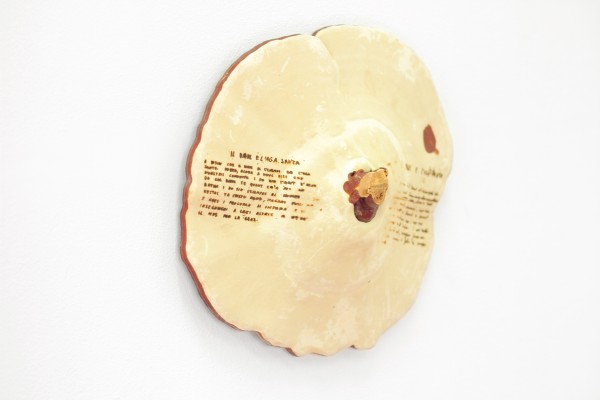

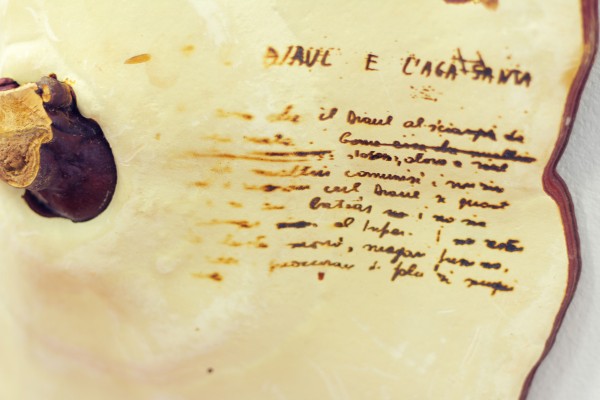

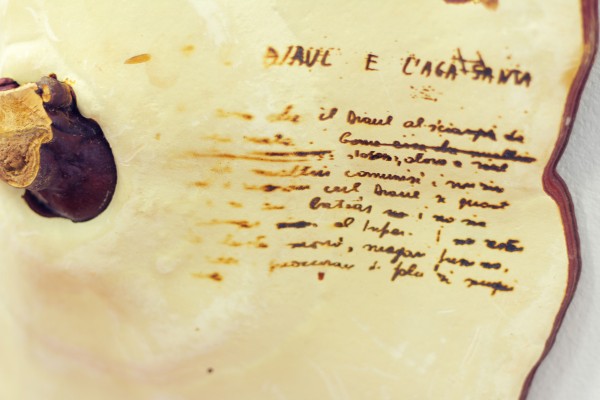

Carlos Reyes, Untitled (After Pindul #1), 2015. Laser-Etched Dried Reishi Mushroom

Carlos Reyes, Pindul’s Rewards, Installation view

Futurism’s social impact was due, in large part, to the timing of its emergence. Its rise occurred during a tumultuous period in Italy’s recent political history. In the years leading up to the First World War, national conciliation between the political Right and Left became unworkable. A series of strikes and riots in favour of suffrage for the working classes – known as ‘Red Week’ – brokered a schism between the rich and the poor; worsening economic conditions resulted in the country being coerced into joining the war. Futurism, which rallied for the mechanisation of industry and promoted the (perceived) magnificent racial qualities of the Italian (who they saw as demonstrating “all the qualities of GENIUS”), increasingly appealed to the Italian public. As the Futurists’ de facto leader, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti ensured that a large section of the Italian population would have access to their series of manifestos because they were printed cheaply and quickly and in great number using the latest in lithographic print technology. With the publication and distribution of their manifestos, Futurism – and subsequent artistic movements – was suddenly able to gain a more public spectatorship than they would have received in just galleries and performance venues.

Carlos Reyes, Untitled (After Amici #2), 2015. Laser-Etched Dried Reishi Mushroom

Carlos Reyes, Untitled (After Amici) #2, 2015. Laser-Etched Dried Reishi Mushroom

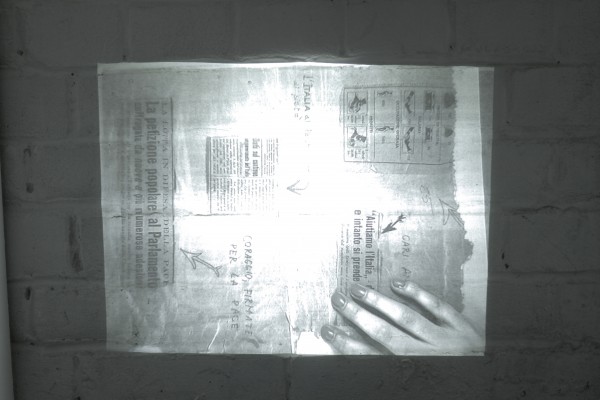

Pier Paolo Pasolini was born in Bologna at the peak of Futurism’s influence in the artistic-political landscape after the First World War. The city and its region, Emilia-Romagna, is renowned for its historic and deep-standing support for the Italian Communist Party – it is known as one of Italy’s ‘Red Regions’. Pasolini would later graduate from the University of Bologna, but as a child his family moved to Casarsa della Delizia, a small town near the Italian-Slovenian border. Casarsa is in the region of Friuli Venezia Giulia, one of only five (of twenty) regions of Italy that are governed autonomously (due to the region’s cultural, racial, and linguistic diversity, part self-governance was granted to the region after the Second World War, in 1947, as an attempt to prevent secession). It was in this highly politicised climate that two years later, in 1949, Pasolini also took pen to paper and had people from the village copy posters by hand to produce a series of political posters as a call to arms for the people of Casarsa. These posters are archived in the town at the Centro Studi Pier Paolo Pasolini and were exhumed by curator Alessandro Bava while working with the institution in 2014, before bringing Carlos Reyes in for the project.

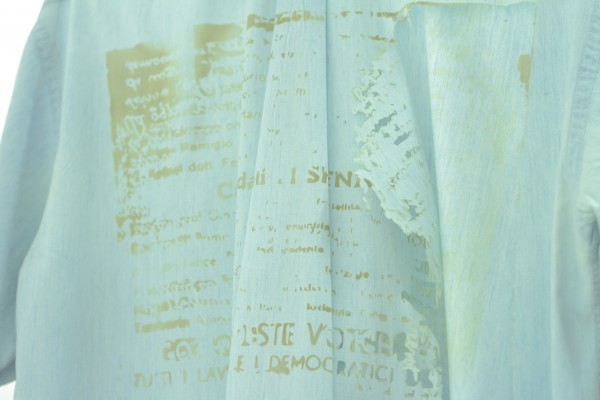

Carlos Reyes, airehgnU ni edecus asoC, 2015 (Detail). Gauze Mesh Shirt, Laser Etched Denim Shirt

Carlos Reyes, airehgnU ni edecus asoC, 2015. Gauze Mesh Shirt, Laser Etched Denim Shirt

For the exhibition Pindul’s Rewards at Arcadia Missa, London, organised by artist-architect Alessandro Bava, Reyes and Pasolini are given collaborator credit on the marquee. Pasolini’s words provide the starting point for this display; Reyes re-performs the texts written by Pasolini for his posters. They have been made into photocopied replications and projected onto the wall, and they have been laser engraved onto shirts and, incongruously – but most effectively – onto wide-capped, dried mushrooms.

Carlos Reyes, airehgnU ni edecus asoC, 2015 (Detail). Gauze Mesh Shirt, Laser Etched Denim Shirt

Carlos Reyes, Pindul’s Return, 2015. Hand Painted Padded and Stretched Film poster, Wine Glass, Rare Earth, Magnet, Ferrofluid

These texts include “The Satisfactions of ‘Pindul’,” a fable that recounts the ‘rewards’ of a politically-blinkered man; a series of newspaper clippings, annotated by Pasolini, that highlight how Italian culture is ultimately undermined by foreign aid and ‘assistance’; and a polemic against the Christian Democratic Party that accuses them of hypocrisy against the poor. Alongside these texts are sculptural elements: a stemmed wine glass containing ferrofluid (a magnetized liquid), and a hand-painted poster for The Matrix Reloaded that Reyes found in China.

Carlos Reyes, Pindul’s Return, 2015 (Detail). Hand Painted Padded and Stretched Film poster, Wine Glass, Rare Earth, Magnet, Ferrofluid

Carlos Reyes, Pindul’s Return, 2015 (Detail). Wine Glass, Rare Earth, Magnet, Ferrofluid

The political message of the show comes through powerfully – Pasolini identified as a Communist, with faith that the State must defend its sovereignty as strongly as the individual rights of its citizens. Any party that claims power within Italy must do so in the name and in support of its peoples. Perhaps this message resonates even stronger at the present time: I visited the exhibition the day after the British general election, when our center-Right minority government won an outright majority on the promise of a more extreme shift to the Right. It was heartening to see that Reyes had replicated one of Pasolini’s recurrent emblems in his collages: the silhouette of a big-bellied man with wide grin dressed in top hat and tails, carrying bags fat with cash. Heartening because it’s an image that has become common in British newspapers over the past few years – it is a similar image used by satirists when referencing Prime Minister David Cameron, a figure mocked for his detached, monied, upper-class background.

Carlos Reyes, Untitled (After Pindul #2), 2015. Laser-Etched Dried Reishi Mushroom (on left)

Carlos Reyes, Untitled (After Pindul #2), 2015. Laser-Etched Dried Reishi Mushroom (on right)

The texts and illustrations appear engraved on mushrooms. It is an interesting material, and one that deserves closer scrutiny. As an organic substance, it begins the process of bio-degradation immediately upon foraging. As a fungus its primary characteristic is that it forms a symbiotic relationship with other organisms and aids nutrient recycling and therefore enables more efficient decomposition. Used in this context, the audience is faced directly with the idea of the parasitic nature of rhetoric (of all persuasions), as well as its rapacity for self-preservation. The mushrooms that Reyes selected for these works are reishi mushrooms. They are incredibly rare in their natural state, found most often today in their dried form. These particular mushrooms were individually sourced and shipped from a supplier in New York. They are a treasured ingredient within traditional Chinese medicine. This strain of mushroom is believed to be around two and a half thousand years old, but it has only been in more common use in the past five hundred years. Previously, it was solely supplied to the ruling Emperor. The reishi (‘lingzhi’ in its Pinyin Chinese name, ‘reishi’ being Japanese) mushroom is believed to preserve the Qi – the life energy. That when taken for extensive periods of time it has the power to preserve life.

Carlos Reyes, Untitled (After Amici #3), 2015. Laser-Etched Dried Reishi Mushroom (on left). Untitled (After Rewards #1), 2015. Untitled (After Rewards #3), 2015. Dried Reishi Mushroom (on top & on right)

Carlos Reyes, Untitled (After Pindul #3), 2015. Laser-Etched Dried Reishi Mushroom

Pindul’s Rewards is an evenly-balanced display, with strong visual elements tempering the artists’ ‘Right On’ politics. But the exhibition’s strongest aspects are those elements that demand close, careful, and detailed scrutiny. Of course, print poster political placards and their distribution don’t necessarily equate to left-wing demonstrative politics (let’s not forget that even the Futurists supported war and would eventually merge with Mussolini’s ruling Fascist Party), but it’s worth remembering the enigma posed by German artist-activist Dieter Ruckhaberle in 1968, in opposition to Documenta 4: “What’s left to do for artists of nation[s] that wage criminal war…other than to make Minimal Art?”

Carlos Reyes, Untitled (After Pindul #3), 2015. Laser-Etched Dried Reishi Mushroom

Carlos Reyes, Untitled (After Arcadia), 2015. Live video feed of take away poster.

Pier Pasolini and Carlos Reyes

Pindul’s Rewards

Arcadia Missa

May 1 – June 27 2015

With thanks to Centro Studi Pier Paolo Pasolini.