Lafayette Anticipation associate curator Anna Colin talks to artist Tyler Coburn about Ergonomic Futures, a speculative project engaged with art, design, science, anthropology and writing. In this interview, Coburn discusses the research, production process and network of collaborators of a multilayered project ultimately concerned with the futures of humankind. Anna Colin: When one comes across your museum seats Ergonomic Futures (2016—) in contemporary art exhibitions—and soon in natural history, fine art, and anthropology museums—they look… [read more »]

#FOMO at ICA

Olia Lialina, Animated Gifs Timeline (still), August 2014

In the last weekend of May, London’s Institute of Contemporary Art hosted FOMO, a three-day conference chaired by German video-artist, professor and philosopher Hito Steyerl. FOMO (fear of missing out) indicated the event’s overarching topic of anxiety – and its socio-cultural-political plentitude in the post-digital or ‘anthropocene’ era. The program featured an impressive cast of international theorists, artists, activist, and hackers, all engaging with contemporary digital existence.

Theorist Judy Wajcman first presented a series of problematisations of the tech industry and digital innovation, particularly in the field of engineering. “The problem is that those who make our technology are unrepresentative of society,” she argued, discussing the visibility and representation of minorities within engineering. “Very limited types of people make very limited types of technology.”

Wajcman, a sociologist at London School of Economics, writes extensively on techno-feminist theories of technology, having recently published her book Pressed for Time: The Acceleration of Life in Digital Capitalism. She also wrote the pioneering book TechnoFeminism in 2004, and has actively championed a transdisciplinary approach to gender-, feminist- and media studies. As it became clear in her presentation, there is an incredible absence of sociological reflection as to what data collection and technology means to gender and identity. Talking of the social sciences, Wajcman posited that art movements are in many ways more progressive than academia in their feminist reflections on digital existence and its implications.

Olia Lialina, Animated Gifs Timeline (still), August 2014

In an increasingly online culture where being ‘busy’ appears as the ultimate imperative, the image of time as ‘accelerating’ is tempting. But in the theorizing of the digital, it is essential to step back and consider other conceptual alternatives. Wajcman argues against the notion that our current ‘digital time’ is radically different from before, reminding us that human existence has always referred itself to ‘time-keeping objects;’ (e.g sunrise and sunset, and the movement of the moon). Rather, the supposed increased speed of the post-digital present can be attributed to the value systems and social perimeters we impose on ourselves today. Hito Steyerl suggested that perhaps it is the idea of rhythm rather than speed that has changed: the orchestration and distribution of time within society may be the most pressing issue of contemporary existence. A caricatural yet real example is that of a breathing app that tells you when and how to breathe.

Next up was net artist Olia Lialina in conversation with critic and curator Karen Archey, who guided the audience through Lialina’s vast history of online work. They discussed her pioneering work My Boyfriend Came Back from the War from 1996, a form of hypertextual narrative where the viewer unravels fragments of a relationship through simple animations and buttons on a website. The work is still online, but Lialina paradoxically admitted that she prefers a single still or screenshot of the piece: the work was created for a slower, 72 kbps connection, that enforced a certain temporality on the viewing of the website. “Today, you click through this work in 5 seconds, rather than 10 minutes,” she explained, returning to the question of digital time. The temporality of the web should indeed be a concern with regards to the preservation and presentation of Internet art – at the recent Digital Revolutions exhibition at the Barbican, for example, the piece was presented with an artificially slowed down connection.

Olia Lialina, My Boyfriend Came Back from the War, 1996

As the Web comes of age, its changing spatiality and vernacular must also be studied. Archey emphasized the notion of a digital folklore – where did it emerge, and where does it exist today (spatially and socially)? As Nina Power suggested at one point, FOMO seemed an appropriate title for the event: a term that emerged online yet is already outdated. One member of the audience pointed out that the Internet 1.0 used to exist almost as a kind of virtual ‘wild west’, its freedom now diminishing with the increasing corporatization and privatization of the Web. Does this changing notion of freedom online, with its fewer autonomous channels, also translate to a diminishing web vernacular? Not necessarily, Lialina argued: today, digital folklore is found equally within the corporate system – as seen, for example, with idiosyncratic, homemade lyric music videos on YouTube. “People find ways to express themselves and create with the tools given to them,” she argued. Post-corporatization, digital vernacular is seen as much within as outside the corporation, with GIFs taken from TV and film being used conversationally on social media, forming a new form of semantic imagery.

Sunday opened with a presentation by artist Yuri Pattison, who has a more architectural or infrastructural interest in the digital and studies the entry and exit points of virtual and material networks. His visit to the underground data centre in Stockholm Bahnhof proves that the architecture of such material networks is retro-futuristically influenced by sci-fi and dystopian cold war architecture; his cinematic documentation evokes both James Bond film sets as well as sci-fi films.

colocation, time displacement by Yuri Pattison

Pattison was recently commissioned by the ICA to respond to their seminal exhibition Cybernetic Serendipity (1968), that articulated many of the primary concerns that came to shape subsequent (new) media theory as well as Internet art. Re-using the classic retrofuturistic gimmick of two chatbots conversing, he constructed his own bot and juxtaposed it with another, so they could converse without human interference. As the bot learns and develops from the millions of conversations it has had with people over the years, it becomes a mirror, a reflection of the always-ideological nature of such content (regardless of its fragmentation), while expressing a certain overwhelmingness over the vastness of such data.

Yuri Pattison, Architectures of Credibility, H.M Klosterfelde, Berlin, 2015.

In the landscape of Internet data, much labor is outsourced to artificial intelligence. However, when this falls short, a new group of online task workers take over. Via services such as Amazon Mechanical Turk, companies and individuals can outsource micro-tasks that robots cannot yet satisfyingly perform, such as image recognition. Under the banner of ‘artificial artificial intelligence,’ such outsourcing creates a new force of largely invisible underpaid labor (often from countries in development such as the Philippines) reinstating the economic hierarchy of the material world on to the virtual. In an attempt to visualize and humanize this network of labor, Pattison posed as a supplier and paid task-workers to take a picture from the window which they usually work closest to; in the 10-minute video work outsourced views, visual economies, Western cityscapes, abandoned graveyards, pastel-colored residential areas and exotic palm groves intermix and gives a portrait of the invisible ‘digital sweat shops’ that sustain our online existence.

outsourced views, visual economies by Yuri Pattison.

Theorist McKenzie Wark continued Pattison’s prism of looking at technology through labour. He most recently authored the book Molecular Red, in which he looks at the anthropocene through a Marxist scope of labor – a condition he described as “the result of the collective labor of 7 billion humans destabilizing the Earth.”

Yuri Pattison, Architectures of Credibility, H.M Klosterfelde, Berlin, 2015.

Wark went back in history to trace and identify labor and capital’s relationship to nature. Alexander Bogdanov, a relatively unknown Marxist physicist and philosopher, almost got the theory of climate change right in 1908, while asking very contemporary questions on how to order and organize the world. He dismisses the idea of nature being something ‘stable’ but rather as something that pushes back. He believed that labor has to defeat capital in order to think about its relationship to nature. “Nature is not providence,” Wark reasserted to the lecture hall, with reference to another 20th century Soviet theorist, Andrey Platonov. Discourses of labor-struggles under neoliberal capitalism naturally become anthropogenic as they clash with nature. This new anthropogenic era of geological history is a sign of both the communist and, now, capitalist empire failing the test of a long-lasting relationship with nature.

Finally, porn theorist and feminist scholar Helen Hester of Middlesex University London deconstructed the much-talked about concept of ‘war porn’, taking examples from the sphere of digital culture. “The changing idea of the pornographic explodes the idea of adult entertainment,” she began, an issue she has explored extensively in her book Beyond Explicit: Pornography and the Displacement of Sex from 2014.

Hester first looked at porn that references or restages current world conflicts, and our anxieties about them (for instance, how Western soldiers are treating Iraqi prisoners, echoing the Abi Ghraib torture scandal). Recontextualized images of religious fanaticism and torture by demonic Arabic men is capitalized upon and used as a preamble for sexual performance. However, what happens when these images of transgression travel online, and eventually feed into an actual political discourse? As Hester argued, both sides of the current ‘war on terror’ have mistaken such footage for genuine.

As a concept, ‘war porn’ is an ambiguous or, as Hester called it, polysemic phenomenon. Non-sexually explicit but gory war documentary footage that began circulating on the Internet in the last decade, tends to also be characterized as war porn, or ‘pornography of pain.’ Today, the idea of ‘the pornographic’ transcends adult entertainment, referring to a vague, larger sphere of explicit and spectacular images of all kinds – within war, but also other themes such as ‘food porn’, ‘furniture porn’ or ‘architecture porn’. Hester argues against such expansion, as it delegitimizes porn as a useful cultural category whilst banalizing actual war torture in the attempt to redirect something as atrocious as war crimes into a more ‘manageable’ sphere of cultural commentary. Paradoxically, such a definition of war porn echoes anti-porn feminism, an argument that worked to diminish the sexual aspect and make the violent aspect central to the pornographic.

As one woman in the audience pointed out, we posses a heavy anxiety of representation in the post-digital, a world in which real, digitally-mediated (allegedly authentic) ISIS-beheadings are consumed in tandem with equally violent but staged pornography.

One of the most complex issues arising from cyber- and techno-feminism is that of embodiment and disembodiment in and after the digital. Feminized labor was a recurring theme: returning to the robot, Steyerl pointed out how “it embodies this old promise of getting rid of labor once and for all.” Wark, in response, argued that “the fetish of the robot never goes away, because we always try to perceive ourselves as non-robotic.”

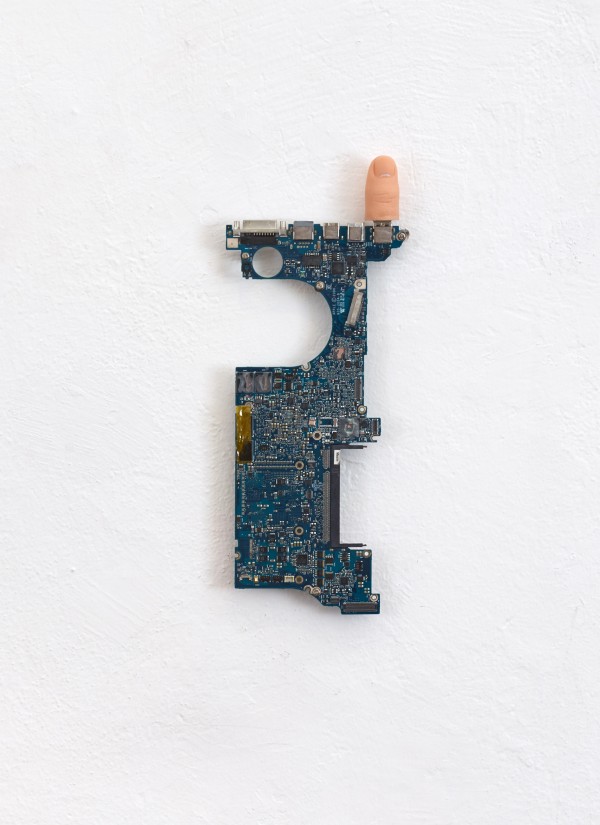

Yuri Pattison, Architectures of Credibility, H.M Klosterfelde, Berlin, 2015.

“Cyberfeminists imagined that you could be disembodied on the Web and actually transcend yourself,” Helen Hester added. “Now the actual body is being put back into the web in more and more ways.” Counter-intuitively, today’s digital landscape sees an insistence on embodiment, with more and more technology being gendered. Almost all virtual assistants avatars, Nina Power pointed out, are female, supporting the misogynist observation that as a women, “‘you can be a voice without a body, or a body without voice.”

Today, fear of disembodiment and fear of bodily incorporation into the system happens simultaneously – ‘we’ acquire bodies and lose bodies, are deconstructed and reconstructed on a data- or other representational level all at the same time. The real anxiety, which predates the digital by millenniums, lies perhaps in the speculation that humans have never been completely bodily – and that subjectivity exists entangled into a larger socius, system or network. The digital not only visualizes but exemplifies this anxiety – and perhaps offers a paradigm in which we can process such a complex idea.

By foregrounding anxiety (in its multitude) in the discussion and analysis of contemporary digital existence, we can find the tools that enable a new world to emerge from this current position of fear, so symptomatic of the 20th century. “Is FOMO,” Hito reflected meditatively in conclusion, “really a fear of missing out of the creation of this new world?”