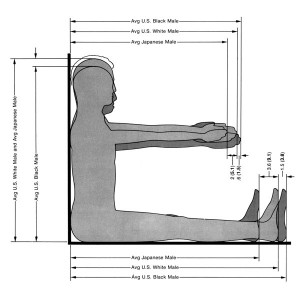

Lafayette Anticipation associate curator Anna Colin talks to artist Tyler Coburn about Ergonomic Futures, a speculative project engaged with art, design, science, anthropology and writing. In this interview, Coburn discusses the research, production process and network of collaborators of a multilayered project ultimately concerned with the futures of humankind. Anna Colin: When one comes across your museum seats Ergonomic Futures (2016—) in contemporary art exhibitions—and soon in natural history, fine art, and anthropology museums—they look… [read more »]

(IM)MATERIAL: Industrial and Post-Industrial Fabrication

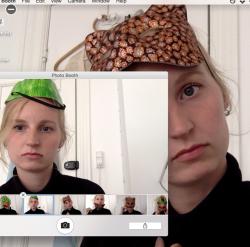

Dora Budor: The Architect’s Plan, His Contagion, and Sensitive Corridors, 2015

Exhibition View at New Galerie, Paris

Courtesy the Artist and New Galerie

Last Friday, the Judd Foundation hosted a panel on the relations of production underpinning fabrication in contemporary art, featuring artists Josh Kline, Dora Budor, and Keith Tilford. Organized by CCS Bard students Adriana Blidaru, Tim Gentles, Jody Graf, Rosario Guiraldes, and Dana Kopel, the event’s presentation proceeded from the premise that a paradigm shift in the economy — from industrial, manual production on the one hand, to post-industrial, digitized outsourcing on the other — deeply characterizes contemporary art making. What transpired throughout the evening was that, regardless of different opinions and creative practices, capitalism constitutes the horizon of possibility for artists and manufacturers alike, and must be reckoned with as such. The question then becomes: how far can artistic reflexivity go before becoming complicit with the economy it seeks to critique?

Global Services by Keith Tilford

Kline opened the evening’s talks by noting the increasingly polymorphous and distributed nature of trafficking today: how, in the eyes of biometric digital technologies, we are constantly being evaluated. “Even when you’re at a party, you’re still at a job interview.” When the divide between the personal and the professional dissolves, taste gets elevated as a productive principle — both as an engine of entrepreneurial networking and a stimulus for economic innovation.

Josh Kline, Tastemaker’s Choice, 2012 (detail)

Directing attention to his more recent work, Kline proceeded to discuss the sculptural methodology behind what he calls the “information portraits” of workers he sought to represent. As automation accelerates and the obsolescence of so-called ‘grunt work’ draws near, the tension between digitized outsourcing and working class labor becomes an object of Kline’s project.

Josh Kline, Packing for Peanuts (Fedex Workers Head with Knit Cap), 2014

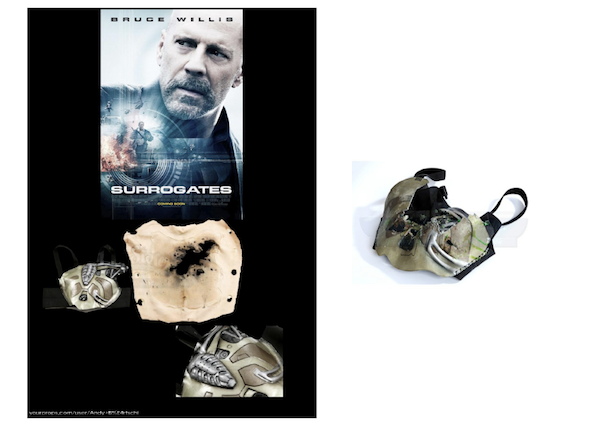

Influenced by the industrial “life cycle” of Hollywood movies — the preordained financial projections and returns on investment that put production into motion — Dora Budor creates a “full circle” with the material leftovers of blockbuster hits, repurposing a prosthetic afterlife of outsourced props acquired through sites like Ebay. The CGI reincarnations of dead actors also serve as a heuristic example for distinguishing the post-industrial aspects of contemporary fabrication: as objects of value, the bodies of dead Hollywood actors are taken up by digital technologies and partitioned into “undead” resources. Budor’s parasitic methodology with regard to contemporary capitalism amounts to a sort of “film without film”, where the excess remnants of cinema become re-incorporated into sculpture.

Budor uses cyborg chest prosthetics from the movie “Surrogates”, starring Bruce Willis

Despite so many advancements in technology that have led to artists’ ability to outsource and circumvent manual fabrication, the question of remuneration still looms. Kline’s choice to represent Fedex workers in Packing for Peanuts is no coincidence (employees of that company are notoriously denied benefits by way of third party contractors) — just as he repeatedly emphasized the imperative to pay people who have a hand in fabrication. Budor likewise claimed not to employ assistants without adequately compensating them. No matter how “immaterial” or “post-industrial” of an economy we work in, this is, after all, still capitalism. And the devaluation of labor, be it artistic or not, stands only to maximize profits at the top.