Lafayette Anticipation associate curator Anna Colin talks to artist Tyler Coburn about Ergonomic Futures, a speculative project engaged with art, design, science, anthropology and writing. In this interview, Coburn discusses the research, production process and network of collaborators of a multilayered project ultimately concerned with the futures of humankind. Anna Colin: When one comes across your museum seats Ergonomic Futures (2016—) in contemporary art exhibitions—and soon in natural history, fine art, and anthropology museums—they look… [read more »]

Tifkas | Rosie Hastings & Hannah Quinlan Anderson

@Gaybar is a multidisciplinary art project and event series, led by the collaborative duo Rosie Hastings and Hannah Quinlan Anderson. Since their graduation in 2014, they have explored the notion of the ‘gay bar’ spatially, aesthetically and politically by re- and dematerializing it in a variety of formats. Through modes of social celebration, critique, and at times, mourning, @Gaybar commemorates the fight for queer spatiality, virtual and real, whilst discussing contemporary sociopolitical issues such as queer assimilation and the ever-growing threat of gentrification in London’s already scarce terrain of queer spaces.

@Gaybar sprung from “a strong frustration with London gay bars,” the couple tells me, as we smoke a cigarette in the spring sunshine, celebrating the install of their first solo exhibition, Tifkas at Arcadia Missa in Peckham, London. “Feeling frustrated with art as well: finding it really fucking boring, and not necessarily expressive enough of what we want to talk about,” they continue, as we discuss the limitations of the channels of showing art and what is accepted in galleries. “So we started talking about the idea of starting a gay bar.”

Tifkas, 2015

The gay bar is a historically contested space: highly politicized yet commercial, socially assimilating yet the actual gathering point for much of the queer community, a site of homonormative visibility that nontheless accomodates a range of homo- and trans-sexualities. It possesses an anxious, ambivalent energy of sexual and romantic anticipation, a sense of historical activism, free yet detained: completely performative, the ‘gay bar’ appears as a strangely suitable host for queer social practice like that of Hannah and Rosie. @Gaybar began as a series of parties at their studio, in which the tropes and conducts of queer spatiality were explored and discussed: “We’d make the bars and then we would install monitors within the bars, showing stuff that we had produced ourselves, like CGI images of imaginary gay bars and digital pride flags. We would curate the music, the Facebook group page, the invitation, etc. We were really specific with the materials we used as well: we always ordered cocktails glasses, which seems insignificant, but is actually a big part of the space we’re creating. We didn’t just want it to be some lame trendy party; there’s an object specificity to the materials we’re using, from the cocktail glasses, to the kind of alcohol we’re using, and the way we serve it. It’s all performatively a part of the work in itself,” they explain.

Tifkas, 2015

In accordance with the sociopolitical reality in which they operate and exist, there is no end of the social event and beginning of the ‘art work’ with @Gaybar – it’s a holistic yet aggressively critical project, fiercely opposing the removed, already-theorized, institutionalized critique of queer. “For our practice I think it’s important to have that open dialogue between the event and the show – they have to inform each other, otherwise the art in the show would really suffer. Our practice would lose what is legitimately good about it.”

In ‘actualizing’ and grounding queer artistic activism in a sociopolitical reality (both past, present and future), the context of viewership is considered, not just in terms of space, but form: “We really wanted to remove the straight gaze from our work,” they tell me, “to not just make ‘queer’ objects for people to come and look at. The art gaze can feel really hetero, and the dynamics between the art object and the viewer can feel really hetero.” By socializing the art works and the viewership (installing lightbox-art works in the parties, simulating the interior of a traditional gay bar), the conventions of consuming art are challenged.

Tifkas, 2015

With the rematerialization of queer iconography, @Gaybar not only examines contemporary or recent gay tropes, (such as the digital pride flag) but carefully revisits the multiple 20th century sites of ‘gayness’, but does so without assimilating that history. “We didn’t want to straighten out the history of gayness, or document it, or archive it in the same way that dominant history does by trying to create this trans-historical narrative of ‘being gay,’ they explain: “that wouldn’t account for the differences in experience of being gay; we don’t want to assign this narrative to this history, that has in many parts been erased, or not allowed to exist.” The tropes of gay mainstream culture are instantly recognizable, yet their significance and echo in visual culture are far too unexplored – falling short of description, words like ‘camp’ and ‘kitsch’ aesthetics are fiercely dismissed by Rosie and Hannah: “We feel that academic terminologies used to describe queer phenomena such as ‘camp’ and ‘kitsch’ is a vernacular appropriated by straight people to make sense of a messy queer experience.” Engaging the gay bar in a social art context calls for the invention of a new critical language.

For Tifkas at Arcadia Missa, the couple have focused specifically on the 60’s and 70’s Americana gay bar, situated within the context of the civil rights movement, a time they describe as “in parts radical, in parts problematic or exclusionary but always very charged; gay people were forced to take on this very political identity: they were seen as political bodies because of their mere sexuality.” Inspired from the 1993 novel Stone Butch Blues, best described as a deeply romantic novel documenting the pre-Stonewall lesbian bar scene and the civil rights movement, the local lesbian bar Tifkas provides a safe space within a largely threatening and unsafe small-town American town – a site of simultaneous celebration and mourning. Similarly, @Gaybar provides a narrative site – a conceptual, virtual and physical space for a pluralistic investigation of queer histories that, to many, are lost or suppressed today.

Between the radical political narratives of 70’s gay activism and today’s assimilated homonormativity there exists a heavy sense of melancholy – an emotional reaction to the highly politicized bodies of past and present. “We’re approaching the subject in a very emotional way,” they explain; “we’re very interested in the affect. What is the affective response to looking at these historical documents and more importantly, how can we engage critically with our affective response? I think that’s almost a more queer entry into history – our collaborator Sam Cottington describes it as radical sensitivity.” Centralizing emotion in past and present queer narratives grounds @Gaybar in actuality – embodied, for lack of a better word, although ‘embodied’ often itself refers to purely political and theoretical concepts. “It’s literally the shit you have to go through on a daily basis,” they add insistently. “That’s why the suffering in Stone Butch Blues seemed to fit so perfectly with this project. It’s so emotionally rich – a rich emotional landscape, which we can inhabit and relate to – allowing us to talk about that history without fixing it to ‘a narrative’ or whatever.”

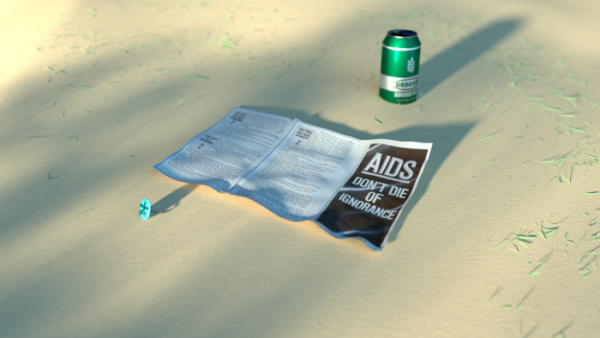

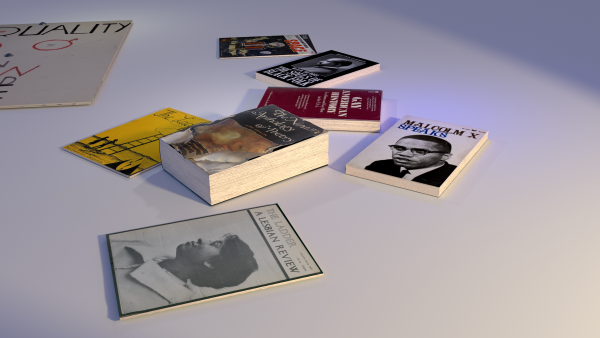

The emotional landscape of queer histories is visualized in Tifkas through a set of CGI-images, depicting a barren and deserted landscape with a single road leading to nowhere, reminiscent of Route 66-type tropes of American road-trip stories. Installed on light boxes in the dimly-lit gallery-space, the melancholic landscape evoke a sense of a loss – a meditative mourning, perhaps, or a general sense of queer dislocation. Scattered objects – referencing specific moments from the book, such as the repeatedly-consumed Genesee beer, or a pile of books honoring past radical thinkers – position the duo’s work within a larger community or project of activism.

We discuss the issues of carving out queer spaces physically versus virtually. Despite digital landscapes and spatiality often being thought of as ‘free’ and ‘tolerant’, the fight for queer space is no less relevant online, and hence the couple approach it with similar attention. “I think we’ve never made that much of a distinction – with creating a queer space online, you have so many crossovers to IRL, and the two really inform each other. The amount of homophobia online is quite similar to IRL – for example, if you’re trying to have like gay space online, you’re often trolled,” they explain, as they briefly describe the kind of virtual homophobia experienced with the project.

Still, @Gaybar, as indicated by their digital prefix, finds a strength in the virtual landscape, and particularly through CGI; an iconographically commercial and ‘straight’ medium, its association is subverted and reclaimed within a queer context. “For us, CGI it’s a really exciting medium,” they tell me whilst finishing their shared cigarette in the sunshine. “Its really magical, and it gives us a lot of access to landscapes that don’t exist IRL. We’re imagining new queer worlds, and creating imagery of those new worlds.” By literally importing past queer artifacts into virtual and physical spaces, the artists imagine new territories and landscapes that propose an actual renegotiation of queer spatiality.