Lafayette Anticipation associate curator Anna Colin talks to artist Tyler Coburn about Ergonomic Futures, a speculative project engaged with art, design, science, anthropology and writing. In this interview, Coburn discusses the research, production process and network of collaborators of a multilayered project ultimately concerned with the futures of humankind. Anna Colin: When one comes across your museum seats Ergonomic Futures (2016—) in contemporary art exhibitions—and soon in natural history, fine art, and anthropology museums—they look… [read more »]

XPO Gallery presents ‘Les Oracles’

XPO Gallery Paris opens a new group exhibition entitled ‘Les Oracles’, fully dedicated to the potent, historically problematic conjunction of science fiction and women- curated by hyperactive artist and curator Marisa Olson, with new works featured from artists such as Julieta Aranda, Juliette Bonneviot, Kristin Lucas, and Aleksandra Domanović. Here, Olson discusses the particularities of the exhibition with Jeppe Ugelvig.

Julieta Aranda, There Has been a Miscalculation (flattened ammunition) Photo#1, Giclee Print, 70 x 60cm, 2007

Jeppe Ugelvig: In which way do the chosen artists incorporate science fiction, or how are their practices informed by it?

Marisa Olson: The ten artists in ‘Les Oracles’ either respond directly to classic science fiction works or more broadly explore the iconography and pop cultural mythologies they convey and inhabit. Some of their projects create new worlds of their own, while others consider the degree to which our present universe is a channel for ideas that were once the stuff of science fiction, each in a wide variety of forms, including sculpture, painting, photography, installation, video, and computer animation. Deploying classic tropes from the science fiction genre, including notions of futurism, fantasy, utopia/dystopia, the frontier, embodiment, fantasy, xenophobia, afrofuturism, cyberfeminism, cosmology & theology, technological change, and evolution, the exhibition takes its title from the concept of the oracle–typically heroic deities, most often female, who act as communicative mediums, providing turning-points in narratives or conversations by speaking to the future in the present.

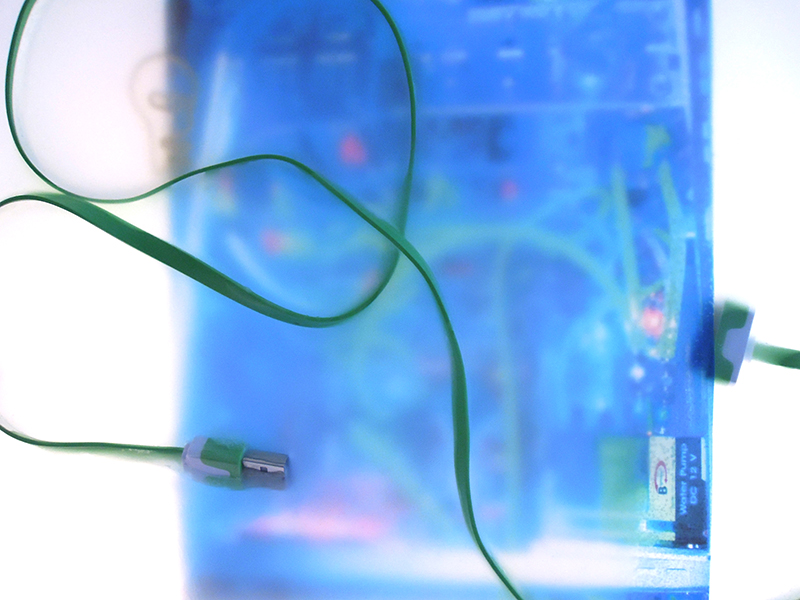

Kristin Lucas, Air on the Go, Video installation, 70 x 20 x 5cm, 2015

JU: In your press release you state that the ten artist you chose “happen” to be female. How conscious or deliberate was the gendered selection of the group? Is there an attempt to move, spatially or thematically, outside the heritage ’patriarchal’ or male-dominated sci-fi?

MO: Yes! I have had a very longstanding interest in the ways that mainstream science fiction has represented women over the centuries. As I started researching films, literature, and critical/theoretical writing in this context, I found that I was very drawn to the large number of female writers and visual artists engaged with science fiction. I decided that if I was to spend my time developing a project on women vis a vis sci-fi, I didn’t want to exhaust that energy bemoaning the historical subjection of women by men, but rather to give a voice to some of these amazing women. In the same spirit, I did not want to contribute to a practice often seen in what you rightly call male-dominated sci-fi: The single, authoritative, dominant, pronouncement-making voice. I didn’t want to do this as a curator (needless to say I’m not a fan of the culture of big ego curating), and in selecting artists I wanted to support many varying practices, approaches, and voices.

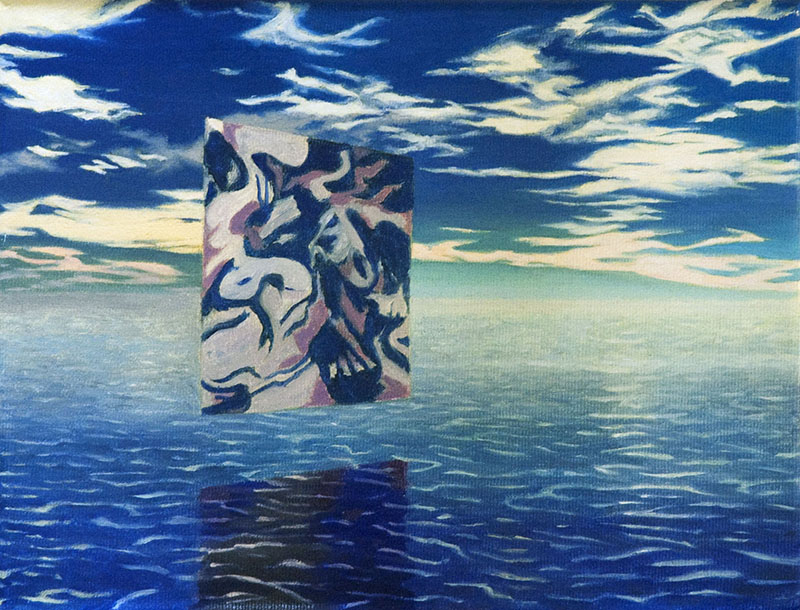

Jeanette Hayes, DeMooning Transformation 1, Oil on vinyl, 46 x 71cm, 2014

JU: In your catalog essay, you mention mimicry as a main element of science-fiction. As an extension of my former question, mimicry becomes important in any queer presence within the traditional genre; the queer body mimicking so as to ‘fit in’, renouncing its subjective agency. Yet, within the ‘new’ landscape of cyberfeminism, this is renegotiated. Where are the queer spaces in sci-fi, or are there any?

MO: Mimicry is a scientific or evolutionary concept that psychoanalysts, queer theorists, postcolonial scholars, and others have variously engaged with to discuss humans’ defense mechanisms and modes of intervention or of passing (racial, cis/gender normative, etc). Science fiction, as a classical genre, is in many ways utterly predictable and hegemonizing, and yet one of its enduring traits is the constant search for and attraction/repulsion towards difference. — Most literally at the site of the alien Other. To me this entire scenario is ripe with queer metaphors, if not ripe for queering. In my catalogue essay for ‘Les Oracles’ I express that I’m most interested in a space of practice along the lines of what Jack Halberstam writes about in the context of the aesthetics of failure. More specifically, I’m interested in the productive breaking of rules (or even their perverse amplification) in order to shrug a grammar that enculturates oppressive power dynamics and superstructures. In the case of science fiction, I’m interested in what I imagine to be the opportunities the genre offers for engaging with the past, present, and future at the same time; for fantasying a better world; and for simultaneously participating-in and parodying the real in a way that allows for productive failure, risk-taking, and social critique. The elements of polyphonics and polyvalence are important here because I’m not interested in perpetuating a notion of queerness predicated upon binary thinking. My organization of this exhibition and selection of these artists was influenced by my interest in many feminist theorists that have called for a disavowal of the kind of patriarchal thinking sci-fi often entrenches and a de-essentializing of sex and gender dyads that also manifest in additional forms of black-and-white or binary thinking-which we see in science fiction as utopia/dystopia, self/other, civilized/primitive oppositionalities. I believe that the work of the artists in Les Oracles demonstrates the possibility of speaking polyvalently or in flipped grammars, of embracing the aesthetics of failure and disorder, of the positive representation of female subjectivity & desire, and of speaking wishfully or informatively about the future without invoking oppressive models of authoritative pronouncement.

Aleksandra Domanović, Things to Come, Installation view, 2014

JU: Historically, the cyborg is a female-gendered figure, simultaneously objectified, fetishized and feared as sexual ‘Other’ – have you approached this figure as problematic, or is she a site of potential agency? I’m thinking here also of the title – the female as oracle, truth-teller or deity.

MO: Actually, despite Donna Haraway’s decidedly feminist ‘Cyborg Manifesto’, I do not necessarily thing of cyborgs as female. Think about The Terminator or even Superman. I think the slippage occurs when people project a cyberbabe/femmebot interpretation onto the concept of the cyborg. The core concept in the cyborg is a coexistence of organic and biomechanical matter – think back to Frankenstein – and then elements of cyborg narratives and theories play out differently as one considers the degree of agency or free will of the being, their level of “dependence” upon this technology, etc. One of the things that is special about Haraway’s theory is that is argues against binarism and polarization of the “natural” and “man-made,” laying out a case for fluidity between these otherwise rigid categories. That said, you are pointing to a very important phenomenon in sci-fi, with regard to the representation of female characters or femininity. In the catalogue I give the example of the maternal figure (drawing on Claire Evans’s great writing about motherships), a nearly universal figure in sci-fi that is problematically worshipped/feared in relationship to her perceived power and intelligence. As with cyborgs, oracles are not necessarily female, but they do often embody a role that can teeter between the perceived feminine stereotype of motherly caretaker versus the perceived tough male gatekeeper prognosticator archetype. I think what’s most important is to ditch these heavy divisions. Critics of such arguments suggest that it is hard to every truly eschew them without first acknowledging (and therefore potentially preserving) them, but I’m in favor of trying!

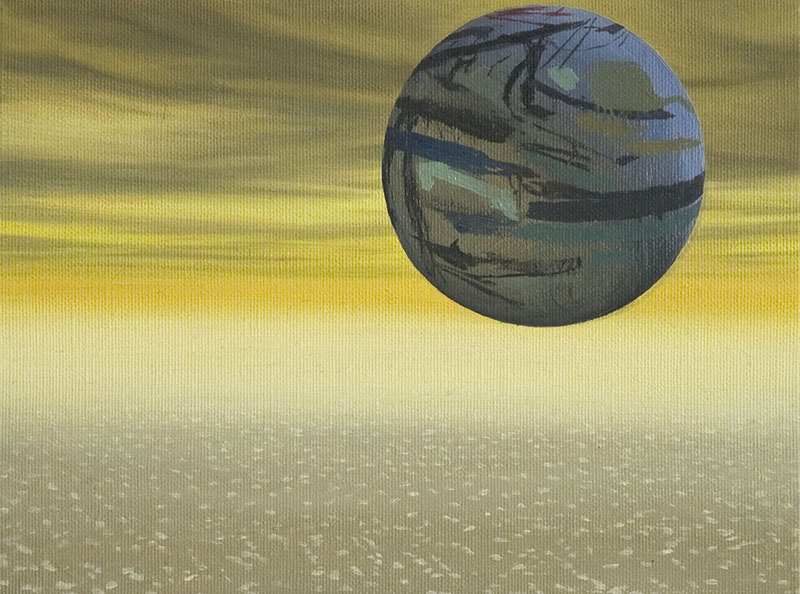

Juliette Bonneviot, Mitchell #2, Oil on Canvas, 16 x 24 cm, 2010

JU: Aesthetically, how does the iconographic history of the genre (and within that, women) fit into contemporary digital or ‘post-internet’ visual culture? Are we experiencing a new interest in its visual tropes?

MO: Though I coined the term Post-internet Art in 2006, I’m not enormously keen on the way that many use the term now. (I recently gave a keynote lecture at Pratt entitled “Postinternet is Dead. Long Live Postinternet!”) I’m more interested in post-internet art in the context of its tendency toward media specificity and its ability to both participate-in and critique contemporary visual culture (which in this case is always already informed by life online). In fact, in this case, I’m potentially more interested in the post-internet than post-internet art, per se, insofar as I see the overall concept as one that can give us a framework for understanding-if not a vehicle for manifesting- what I call “the symptoms of network culture.” Though there are a few artists included in the show that are often grouped under the post-internet heading, I didn’t organize it as a post-internet show – I would hardly see the need to, as my take on post-internet art and culture is that it just IS, it just exists, so every phenomenon, every artist, every art work within networked culture is already post-internet. That said, post-internet art does forward new creative problem-solving strategies for media-specific, self-reflexive critique. In this sense I think there is a clear affinity to working within the parlance of science-fiction, where there is a highly-attuned play of difference between elements of sampled and constructed realities.

Katie Torn, Breathe Deep, Single channel animation, 2014

JU: In the end, what do you feel the show communicates? Is there a mood, direction or sentiment arising from the final exhibition?

MO: Talking so much about otherness, objectification, alienation, etc. can lead to a doom-and-gloom feeling, but overall I think that the show embodies the most exciting, fun, and ambitious aspect of science-fiction, which is its sense of wonder. Many of the works are playful, sexy, mysterious, or funny in the diverse means by which they offer new ways of picturing the world. This is ultimately what drew me to science fiction in the first place. I am enamored with these ten artists and I think that each of them opens the conversation of women and science fiction up in beautiful and thoughtful ways. I’d refer to the artists as “oracles” insofar as they work as communication mediums, conveying a glance upon the future in the present, each in unique and perspective-shifting ways.

Katja Novitskova, Shapeshifter 12, broken silicon wafers, apoxy clay, nail polish, appropriated acrylic case, appropriated wooden capital, 25 x 37 x 13cm, 2013

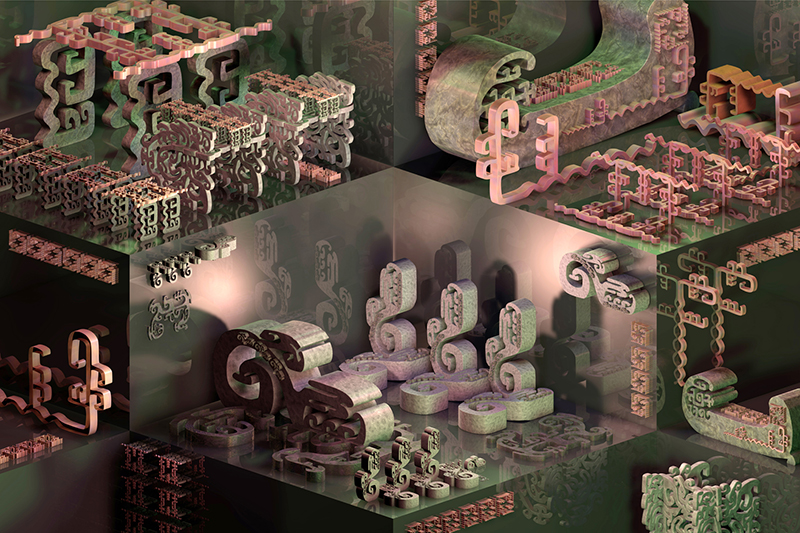

Brenna Murphy, nanostrand-ceremony, archival pigment print mounted on dibond, 150 x 100cm, 2013

Juliette Bonneviot, Brooks #2, Oil on Canvas, 18 x 24 cm, 2010

Caroline Delieutraz, Embedded files, blocks of paraffin, desk (glass, trestles), lights, 80 x 70 x 80cm, 2014

Jeanette Hayes, DeMooning Transformation 3, Oil on vinyl, 46 x 71cm, 2014

Juliette Bonneviot, Mitchell #1, Oil on Canvas, 18 x 24 cm, 2010

Julieta Aranda, There Has been a Miscalculation (flattened ammunition) Photo#7, Giclee Print, 70 x 60cm, 2007

Saya Woolfak, ChimeTEK: Hybridisation Machine, Video, 2013

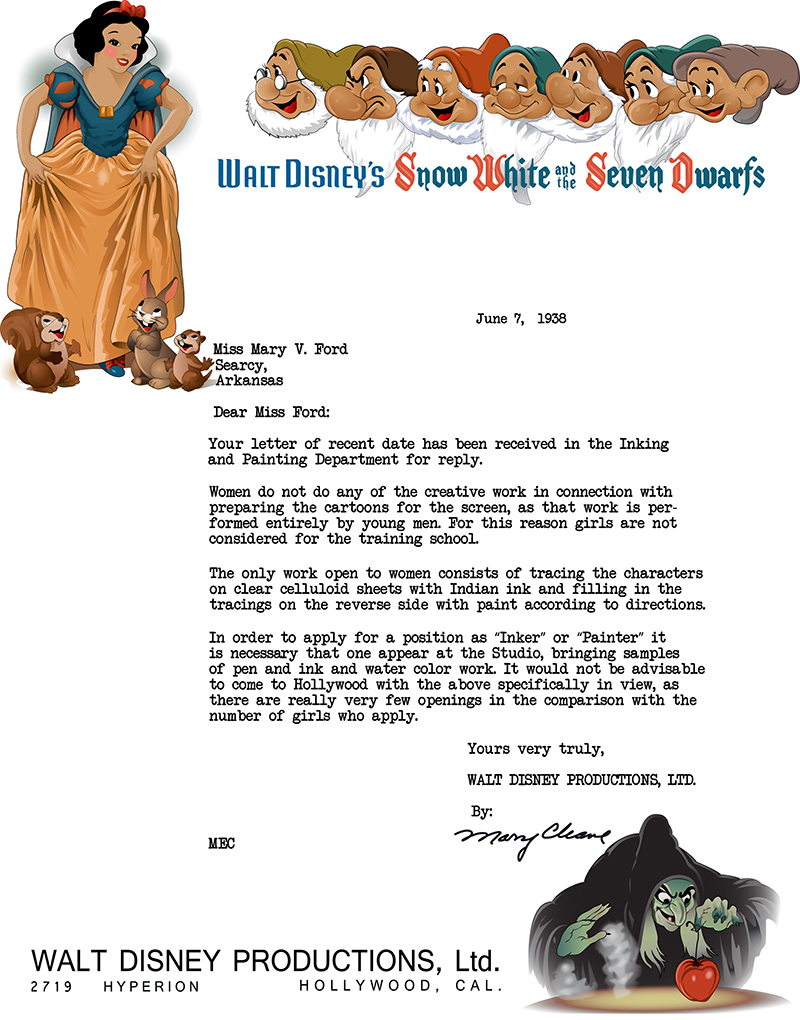

Aleksandra Domanović, Disney Letter, Detail from Things to Come, 2014

XPO Gallery

17 rue Notre Dame de Nazareth,

75003, Paris

from 12th of February, until 4th of April