Lafayette Anticipation associate curator Anna Colin talks to artist Tyler Coburn about Ergonomic Futures, a speculative project engaged with art, design, science, anthropology and writing. In this interview, Coburn discusses the research, production process and network of collaborators of a multilayered project ultimately concerned with the futures of humankind. Anna Colin: When one comes across your museum seats Ergonomic Futures (2016—) in contemporary art exhibitions—and soon in natural history, fine art, and anthropology museums—they look… [read more »]

Dancarchy | Naomi Fisher

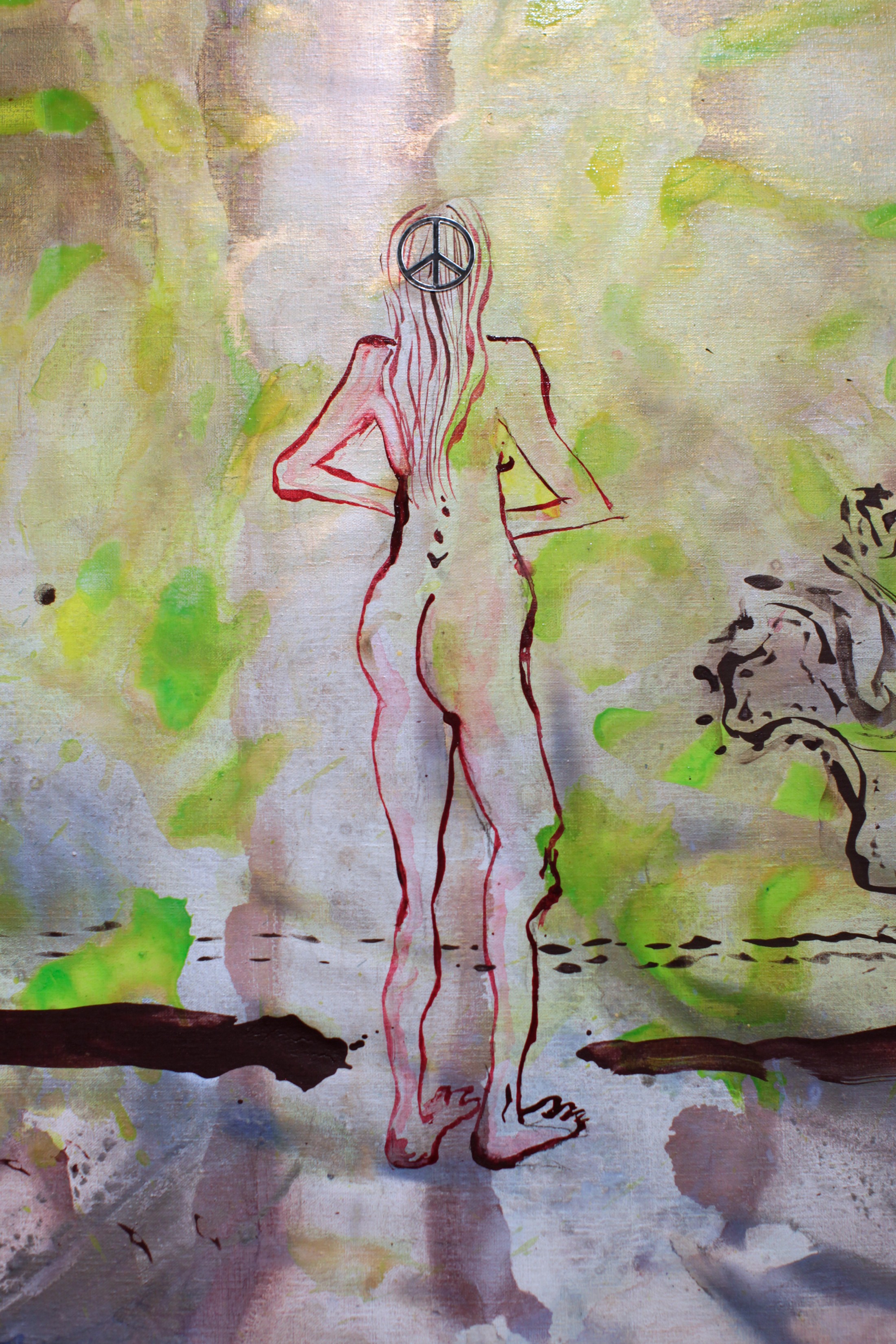

There is an intense new energy unveiled in Naomi Fisher’s new work for Art Basel Miami Beach 2014. Seven large paintings dance their way into the art fair and represent a solid return to painting for an artist who has been dedicated to an aesthetic where nature, ornamentation, and female collective groups dance together and perform their way through the mundane and the extraordinary. Fisher is also revealing a new public commission at the botanical gardens, taking a new interest in size, scale, architecture, and public space. I had the pleasure of spending some time with Fisher while she was on a residency at the Frida Hansens Hus in Norway, and we sat down to talk about the impact the residency has had on her practice and in particular how it has shaped the new work which is shown for the first time during Art Basel Miami Beach. Find out more about PFM painting & decorating in Barry

Geir Haraldseth: Could you talk a little bit about the invitation you got from Art Basel? This invitation has led you to produce a whole new body of work, so I would like to know how an invite to make a project for an art fair turns into such an interesting and bold endeavor!

Naomi Fisher: Last year Art Basel made a similar invitation for the Nova section, where the younger galleries are, at the fair in Miami Beach. I think they wanted some activity in that section, so they asked myself and Jim Drain to come up with a project for them. At that point, the two of us were running BFI, the Bas Fisher Invitational, where we were doing a lot of interactive projects and commissioning performances, doing the Weird Miami bus tours and programming different exhibitions, so we wanted to do a project that was both our own work, and brought in the curatorial side of what we did with BFI.

GH: So BFI do a lot of community work?

NF: Well, define community.

GH: In this case I think it means that you are aware that there is a community out there that you want to engage, seeing as you are providing some services to show your personal take on Miami.

NF: Yeah, BFI and what we are doing with Weird Miami bus tours is trying to take what was interesting and exciting about Miami, and to show people why we chose to be based here. This is also related to the art fair, because so many people just come here for Art Basel and wouldn’t really understand why it would be so interesting living here. They would just go to a restaurant on South Beach and ask me: Why do you live here? And I would say: This is not my Miami. I usually don’t go to South Beach unless I am here with visitors for Art Basel! That program is trying to bring what I think is interesting about Miami into a larger dialog.

GH: So when the invitation came back again for this year, what did you decide to work on and why?

NF: Art Basel were so psyched with what we did last year, and asked for a new proposal, so I came up with a solo project. A lot of my work over the past five years had been coming out of projects generated through research and reacting to specific sites performatively. I have been working with groups of collaborators who are heavily involved in contemporary dance and a lot of that work ended up as videos, or sometimes works would support that, whether it be painting or photography. That all evolved into a show I did this summer at the Home Alone 2 gallery in New York, where three giant paintings, custom made for the space, had ballet bars attached across them. To me, the exhibition brought all the things I was doing performatively into two-dimensional objects as paintings. I started as a painter and got more into photography and performance, and now I am coming full circle, returning to painting again. But the questions that come up from this project are interesting. Is it a painting, is it a functional object, is it a sculpture? The work really questions painting in a way I found really exciting.

GH: Well, it is painting as a utilitarian object, but the new work is still decidedly a return to painting with a focus on what painting is. When I first met you, you were working very mixed, with video, painting, and photography, and now the focus of your output is painting, but it still has all of these other things attached to it. Why do you think there is such a focus on painting in your practice again?

NF: One thing is a frustration with, or just a shift, in photography. I love how open photography is now, but it definitely has complicated my practice as an artist making photographs as art works. I am obsessed with Instagram and how so many people have access to making photographs and images, but it has really changed how I look at photography as an artwork. That shift is what geared my work more towards video and performance. So many people were making interesting photographs, and I was shocked at how banal they were. In a good way! Making very perfect large format Cibachrome prints felt a bit off, and the more point and shoot side of my photography felt too much like Instagram, but it is part of my history as an artist.

#Puzzled, 7×5 feet, acrylic, mirrored plexiglass, ballet barre on linen, 2014

GH: I just wanted to pick up on the thing you said about banality, but in relation to the paintings you have been working on for this project. They are large-scale paintings with definite references to other painters through history. There are some Norwegian painters in there that I recognize, mixed in with other influences, and there is definitely something banal going on as well, which might match some of the attraction you found in this moment in contemporary popular photography.

NF: I think the banality is coming out in my paintings in a funny way. I’ve been intrigued about the shift towards abstraction, which has happened in the last decade. Most of the artists that have been making interesting critical work have been coming out of a tradition of 70s abstraction and process based abstraction, and I think there are a lot of really incredible artists in that category, but it has also dominated the art world in a way that has squashed the weirdos. I consider myself one of the weirdos for sure, and what I think is weird and complicated in these paintings is this adoration of historical painting mixed with a very washy, plain set painting style, with added weirdness, such as the mirror puzzle pieces stuck to the paintings. It looks stupid, but I kind of love it. What is so interesting about culture right now is how stupid it can get. Add to that how fixated on luxury people are, it is important that they are large-scale paintings, which is part of the luxury side of the art market. There is nothing more luxurious than a crazy giant painting, but then what happens when you add a ballet bar to it? What happens when you add a puzzle piece mirror ordered from Amazon? Is it still this luxury painting? Is it more than that? Seeing as everything is mashed up in our time, you can find an Edvard Munch reference next to a tracing of my body doing a dance move, but looking like Michael Jordan’s

GH: Or is it Munch? And everybody wants to have a Munch, speaking of luxury. I have never been able to buy a Munch, but if I had money I would buy a little Munch for myself, but now I can have a Naomi Fisher instead! A Fisher Munch with Air Jordans. It is important to note the scale of the paintings, but also how you insert yourself into that narrative, that is what is exciting to me. Can you talk a little bit more about the installation? There will be seven large-scale paintings in the space?

NF: Yes, all of them are five by seven feet, most of them with ballet bars attached. Every day at the art fair, from 3-5 pm, there will be dancers who are trained in ballet, doing traditional ballet exercises with the paintings as ballet bars.

GH: So it is similar in some ways to the show at Home Alone 2, but with added bonuses. And more barres.

NF: All the paintings are completely new and they are coming out of the show in New York, and the work that I was doing while in Norway for two months at the Frida Hansens Hus residency in Stavanger. The time at the residency helped free up the imagery that was in my head. I was in Norway at the same time as Oil North Seas fair and walking around that fair, looking at all the branding of that world, threw me for an amazing loop, which I am still processing and it is also coming out with this work.

GH: And while Norway really doesn’t have an art market, it does have an oil market. It’s funny to compare one fair to the other.

NF: Yeah, it was the Art Basel for oil!

GH: How was it?

NF: It was incredible! Some of the slogans were insane! I used a Haliburton tote bag for my show at Studio 17 in Stavanger and put a drawing of a crying mermaid inside.

GH: Where she belongs!

NF: Yeah. There was so much going on, freebies, insane quotes, and exposure to something very alien. One bag had oil spurting from the sea with the Eiffel tower on a ship. Are they trying to make a horror story or advertise their products?

GH: Yeah, is this a dream or a nightmare?

NF: There was one booth at the conference saying: Sculpting the Future. There were a lot of overlaps with issues that I see in the art world, which I though was interesting.

GH: Yeah, there are plenty of interesting overlaps! The Nova section where you are exhibiting functions to bring in new talent and the space that you are constructing at doesn’t just have ballet barres, but it is a make-shift bar as well?

NF: There will be cocktails, and booze, but I requested having coconut water there, to have some healthy options at hand. The fair becomes a nightmare where you can only eat and drink what is provided for you.

GH: I always have to have my liver replaced after Basel.

NF: That’s why I wanted to request some healthy options too. I want my bar to be a sanctuary, or a refuge.

GH: And that’s what the title of the piece alludes to?

NF: Yes, it is called Dancarchy Refuge, whichever you are, or need in the moment. There will be a row of plants where you can hide and cry behind.

Ushering in Jupiter, 7×5 feet, acrylic, mylar tape, ballet barre on linen, 2014

GH: Thanks, I might need it. I imagine you have always been painting, but have you always been dancing? Where does the interest in dance stem from?

NF: The interest in terms of my art is largely from the collaborators I have been working with for years. There is actually a nice crossover when speaking about bars, two of the people I had been shooting a lot over the years were dancers, and they actually opened a bar in the lower east side called Café Dancer. Jessie Gold and Elizabeth Hart were traveling so much for their work as dancers and needed part time work, and they become bartenders. They thought opening up a dancer owned bar would solve some of the problems. But it is very challenging to own a business in the lower east side with the rising rents, and it hasn’t solved all their problems, but it has turned into a place where both dancers and people in the art world tend to congregate. After they had been in my projects for years, they asked me to do a project for them, so I did a 60 feet mural down their wall. It’s a long narrow space and that is the biggest paining I have done to this day. The two of them were the inspiration to do the mural. After doing that huge work, all I wanted to do was paint.

GH: And that was mostly that due to the large scale? You have also been doing large architectural public commissions lately, so does that have something to do with it too? There is certainly a huge shift in scale happening in your work at the moment.

NF: Absolutely, once I started working really big I was surprised I hadn’t done so before. And it has made me think of the financial side of things and the disparity in the art world. There is so much talk about the difference between men and women in the market and it started making me realize that the disparity starts very early on. If your work sells, you can make slightly larger work and demand higher prices for your next show. Suddenly all the dudes are making giant painting and the women aren’t. In retrospect I realize how trapped I was in making smaller scale work, so when I starting working on my first large public sculpture commission, I was really psyched, not just because it is this incredible art work and wonderful opportunity for me, but because I am one of the few women who is in that arena.

Try Listening, 7×5 feet, acrylic, mirrored plexiglass, ballet barre on linen, 2014

GH: Scale and gender are exciting things to look at, it’s just a complex issue.

NF: Yeah, and now that I have done some big scale work, that’s all I want to do!

GH: You also mentioned a different shift in your painting, in addition to the change in scale, which happened during your residency in Norway, could you talk about that? It is very exciting for me to see the new work after having the opportunity to spend time with you in Norway and seeing how you reacted to some of the Norwegian painters. And what you did with layering in the exhibition at Studio17 in Stavange, dealing with abstraction, figuration and decoration!

NF: This really surprised me! I used the time in Norway to free myself and paint anything that came into my head. I was also limited to a smaller scale and only doing works on paper. The limitations in scale and paint became an exercise. There were no restrictions beyond that. This meant that a lot of things ended up staying abstractions – the moment something felt done, I moved on to the next. I worked really quickly and made around 100 works on paper during the course of two months. A work could be a single line on paper, and if I liked that line, I was going to leave it! When I came back to Miami and started painting for this project, I had this huge freedom in my hand, and as someone who has been bouncing between media, it always takes a little bit longer to regain a certain freedom in painting. I imagine if someone who has a daily painting practice might never have this rusty, relearning how to ride a bike feeling. And I didn’t have that when doing the big paintings, which felt really freeing and fun. In terms of layering, it was one of the things that happened at the end of my residency when I was invited to do an exhibition at an artist run space, Studio 17. We figured out a way to hang all the work I made in Norway, by putting one piece on top of the other, and when a smaller piece was on top of something bigger it created a collage, which could also function to semi-censor the work underneath. I would only want a hint of some things out there, and the idea of layering definitely complicated and freed things up at the same time. It made everything less precious. And with the big paintings for the fair I would think to maybe just put something on top of it later. This is not happening as much as I thought it would be now, but the ballet bars and the mirror pieces are part of that.

I think even more than the layering, and technical side of painting, I’ve learnt to embrace the goofy side of things. Being a technology obsessed person who lives in front of the laptop, the imagery you connect with online is so tied into that complex mix of images that are coming out from art history, from surfing the Internet, or looking at logos from the oil festival. I spent a lot of time looking at the Norwegian landscape, and the colors I would use in the paintings, the people I meet, and how I represent these meetings, through narratives and abstraction. I feel that in the moment where process based abstraction has ruled so much, it is so freeing to access the goofy irreverence in life. It is part of daily life through Instagram and the Internet, and even though these paintings for Art Basel are traditional paintings, just acrylic on canvas, they are also coming out of this complicated identity offered through the technology that we use in our lives and to live.

Outrage Fatigue, 7×5 feet, acrylic on linen, 2014

GH: You mentioned Munch as one reference, can you mention some other painters that are directly referenced in the piece?

NF: Yeah, there are other Norwegian painters that I was not aware of until I came to Norway. One of them is Arne Ekeland, and I first saw this incredible painting at the Stavanger Kunstmuseum, populated by ghostly white figures, one of which was wearing a drapy, green vest. Some of the figures were holding flowers and I wasn’t sure if they were ghosts or aliens, and I couldn’t figure out what was going on. It was such a crazy beautiful weirdo painting. His work from that time was so incredible and the later work got worse and worse until it looked like something you would see at a Holocaust memorial.

GH: Well, a holocaust for aliens.

NF: Yeah, there was this alien suffering. And I was really into it. Steffen Håndlykken, who runs 1857 in Oslo, told me that if I was in town on a Sunday, I could not afford to miss the Vigeland mausoleum.

Dancarchy Refuge, 7×5 feet, acrylic, ballet barre on linen, 2014

GH: Yeah, Emanuel Vigeland is the less famous brother of Gustav, who made an entire sculpture park in the western part of Oslo. But Emanuel’s mausoleum is something special!

NF: So I had to go, because it is so rare when someone tells you about something you can’t miss because it will blow your mind, you have to do it! And it did blow my mind! It was the craziest thing. You walk into this small door and everything is dimly lit, like candlelight, and you can start to make out an orgy of MILFs and babies, and on the other wall is just a plain orgy. Over the door there are two skeleton fucking. Its gothic weird, depressed, and horny.

GH: And that is his own testament to himself as a person and a painter!

NF: I am really glad he was so crazy so I could experience that!

GH: Well, the exhibition at Art Basel isn’t your mausoleum, but one of the things I see when I look at the new work, is that there is a certain energy there, and a freedom, a fearlessness. Is that too much to put on your work?

NF: I am glad you see that. Any artist is always asking questions to themselves. But the questions I am asking myself with this work are not fear based. It is the opposite, so it is nice to hear you use the word fearless. The entire time in Norway was about getting rid of any fear I had and anything that was restraining me as an artist, by barfing out anything that was in my head. I got through many layers of self-censorship when I was in Norway, and it is not that I am here in the studio in Miami making big paintings with absolutely zero fear, but I would say that these paintings are pretty free. No fear.

Caveman Catharsis, 7×5 feet, acrylic, mirrored plexiglass, ballet barre on linen, 2014

More about Naomi Fisher

More about Geir Haraldseth