Lafayette Anticipation associate curator Anna Colin talks to artist Tyler Coburn about Ergonomic Futures, a speculative project engaged with art, design, science, anthropology and writing. In this interview, Coburn discusses the research, production process and network of collaborators of a multilayered project ultimately concerned with the futures of humankind. Anna Colin: When one comes across your museum seats Ergonomic Futures (2016—) in contemporary art exhibitions—and soon in natural history, fine art, and anthropology museums—they look… [read more »]

The History of Non-Art: Part 3

On the Avant-garde as Rearguard

The most groundbreaking art of the 20th century is called avant-garde. But perhaps these pioneering artists were not so pioneering after all. The artistic avant-garde did not break with established genres and traditions so much as it systematically established genres and tradition. Much of what is considered “radical,” “innovative” and “original” about Duchamp and the artistic avant-garde was brought into existence by people who were not visual artists. They were rather what in the art world is known as ”non-artists,” such as journalists, designers, writers, commercial artists and satirists. What is new in the art world is often new only in the art world.

Chapter 3: Filling in the blanks

In 1952, the piano player David Tudor enters the stage to premiere John Cage’s composition 4’33’’. He sits down at the piano and when he leaves it again, he has not played a single note. Nonetheless, John Cage (1912-1992) came to consider this his finest work. The audience was supposed to hear the sound of silence. The sound of the wind outside, of raindrops falling on the roof, people chatting or even leaving the room. Today the piece is one of the most referenced works in the history of 20th century music and sound art. A couple of years ago, MoMA acquired the oldest existing version of the notation. The composer Arnold Schoenberg, who was Cage’s teacher, was impressed by his student: “He’s not a composer, but he’s an inventor—of genius.”

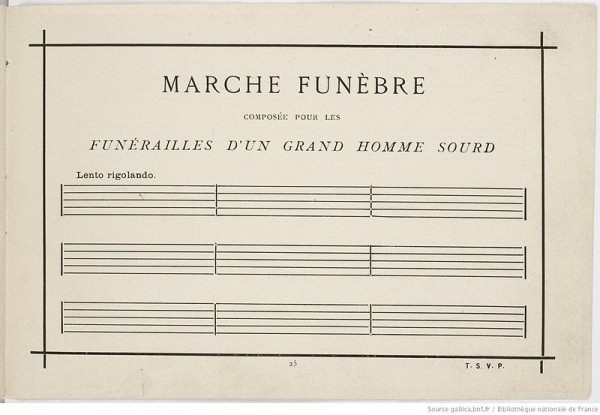

But already in 1884, the author Alphonse Allais, who was not a composer either, presented a notation sheet without notes. He called it “Funeral March composed for the Obsequies of a Great Deaf Man.” And so what? This parallel has often been made – and often been categorized as a curious coincidence.

No joke

For Cage it was of utmost importance to stress that his seminal composition was not “a joke.” It was so very important, because in the beginning it was quite a laugh. No wonder, since Cage, also known as a mushroom expert back then, would sometimes pop up on American and Italian TV shows, performing Rube Goldberg-like sound pieces in a slap-stick manner.

As the Italian newspaper La Stampa amusedly quipped: “The piece was titled Amores and it sounded like a funeral march.” For Allais, however, being fun or not was not a hassle. Allais seemed to consider himself so much ahead of his time that this in itself was a joke. As he already announced in the 1880’s, he was but “a student of the great masters of the 20th century.” And much seems to indicate that these masters were not beyond the influence of their student.

Many of Cage’s role models were connected to Alphonse Allais – directly or indirectly. One of them, the composer Erik Satie (1866-1925), who among others is known for his “Furniture music” destined to play in the background, was one of the composers Cage himself performed. Erik Satie, whom his friend Allais nicknamed Esoterik Satie, was born in the same street as Allais and went on to perform at the café Le Chat Noir, where Allais and his incoherent artist-colleagues would hang out.

The best obsequies

Another of Cage’s heroes was yet a friend of Erik Satie, the artist Marcel Duchamp, of course, whom Cage admired immensely – just like Duchamp admired Allais. Duchamp’s laid-back public persona recalled that of Allais, who defined an idler as someone “who does not pretend to work.” Duchamp even adopted Allais’ drag-like alias Rose Sélavy – kind of similar to the way in which Allais himself had hijacked a pseudonym from a colleague of his, claiming they were the only two allowed to use it. More importantly, however, in this connection, Duchamp seemed to share his predecessor’s taste in music. Duchamp, who might neither be considered a composer, nonetheless composed a few pieces such as “Hollow musical exercises for the deaf” where people were supposed to listen to the notes not being played.

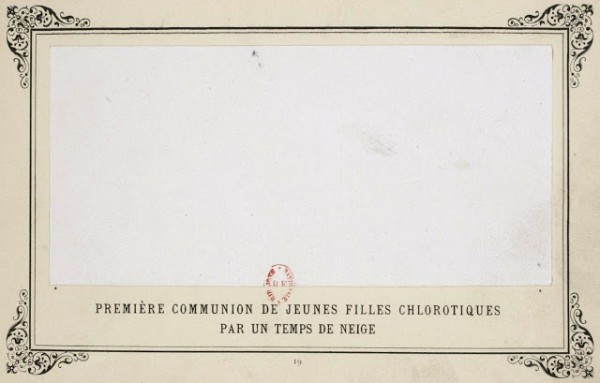

However, Cage was not only inspired by music, but also by another admirer of Duchamp, Robert Rauschenberg (1925-2008), whose white monochrome paintings in 1951 motivated Cage to go through with writing a notation without notes. But already in 1897 Allais made the same step from monochrome to silence. At the end of his small book “Primo-Aprilesque Album”, after his seven monochromes, he put in his notation without notes. In a short manual-like preface to his funeral march, Allais stipulated in a French packed with puns: “Since great pain is mute, the executors should solely be involved in counting the measures instead of giving into this indecent tapping which cancels out the solemn character of the best obsequies.”

Toke Lykkeberg is a critic and curator.