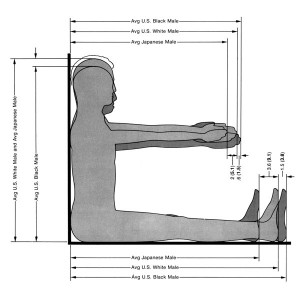

Lafayette Anticipation associate curator Anna Colin talks to artist Tyler Coburn about Ergonomic Futures, a speculative project engaged with art, design, science, anthropology and writing. In this interview, Coburn discusses the research, production process and network of collaborators of a multilayered project ultimately concerned with the futures of humankind. Anna Colin: When one comes across your museum seats Ergonomic Futures (2016—) in contemporary art exhibitions—and soon in natural history, fine art, and anthropology museums—they look… [read more »]

The Word “Remix” Is Corny.

WHY

1. Eugene Levy

The word remix is now corny due to its associations with the lost fashionability of a certain “mash up” trend in music that happened too recently to be considered retro chic and too long ago to be considered contemporary; it’s caught in a purgatory of taste. Being 500 blog years old (5 human years) doesn’t make something “vintagely” sexy; it just makes it more difficult to find when going through a blog’s infinite scroll. Today the word “remix” is associated with mid-2000s bloghouse mashup bands like Girl Talk, Danger Mouse, Justice, Digitalism, and 2 Many DJs, taking up the same “that didn’t age very well” guilt that electroclash formerly held in every hipster’s memory. What started as a surprise combination of The Strokes’ guitars and Christina Aguilera’s voice soon turned into a perfunctory process where one bad song was combined with another to create the short-lived thrill of hearing them simultaneously, an experience on par with the accidentally collaborative odor of a Porta Potty. There’s a deleted clip in American Pie 8: This Time It’s Personal where Eugene Levy walks into his grandson’s frat initiation with a sideways visor, holds up some CDs in one hand, and boasts an illegible gang sign with the other, yelling out, “Hey y’all, check out these remixes!” and everyone’s like “Grandpa!” as they roll their eyes. That didn’t actually happen but you get my point: we hate being reminded of a past we can’t boast about.

2. From The Critique of Institutions to the Institution of Critique

The second possibility is that the word remix has lost its status as a countercultural verb and become a symbol of a Copyright War where there is no longer a mainstream culture to counter. The bad boy cool of remixing something used to be a byproduct of its status as an illegal and occasionally despised act. There was a real danger in remixing during the time when hip hop artists were routinely being taken to court for their use of obscure samples or when artistic appropriation was first being explored wholesale. Today’s DMCA warnings sent to dorm rooms pale in comparison to the aggressive lawsuits previously brought forth for taking without asking. The newfound dominance of the blogospheric internet as a music source has rendered enforcement of those copyright laws a whack-a-mole exercise in futility. The artistic tactic of appropriation is so canonized that when the occasional copyright dispute does come up, it now feels more like a cynical ploy for attention than a legitimate debate over ownership and use—“Ah, I remember when people actually got pissed off about using their pictures.” The general public has reached a verdict on remixing, and they are pleased to announce Not guilty. Remixing is built into YouTube’s interface, remixes are featured in practically every episode of Glee, and the act of remixing was turned into a video game by Activision. In only a decade or two, we went from protectionists to theft-enablers, willfully posting every song, essay, and image we create online for free. Open Source licenses displayed on websites now appear to be overly zealous commandments on the part of their promoters to “please steal my work; I should be so lucky!”. The Open Source logo is, for the digital generation, what the Coexist bumper sticker is for baby boomers—a harmless if meaningless display of one’s standing as a good liberal. It’s now assumed that by virtue of simply placing something on the internet you are consenting to it being stolen and thus remixed. Remixing is no longer a stand against normative ideas of authorship; it’s the embodiment of it.

3. Pomo Blues

The word remix has become emblematic of the collective malaise felt toward the nihilism of postmodern authorship. Kicked off by Roland Barthes’s death of the author, the idea that contemporary culture was merely a combination of parts from the past became very popular in polemicized postmodern discourse. Some variation of Douglas Huebler’s quote “The world is full of objects, more or less interesting; I do not wish to add any more,” has echoed in the artists’ heads ever since. While it’s inevitable that future creations will always be indebted in some way to the past, this totalizing idea—that nothing new can or ever will be created—is routinely disproven by the reality around us. In art, the new is created out of the past’s inability to accurately represent the present. This cannot be made up for merely by recontextualizing or appropriating previous messages alone but must include the invention of new materials, messages, and mediums as a response to changes in technology, culture, politics, science, etc. As mediums change so do their messages: you can’t play an MP3 on a Walkman. Remixing can only be understood as the end-all methodology for cultural production when you believe the number of actions, messages, or mediums that can be employed are permanently limited, where you are granted a number of historically determined variables for the construction of meaning and must proceed into the future by repeating and mixing them ad infinitum. Not everything can be explained away as a remix of something else because of the existence of historical anomalies, events that break from the assumed trajectory of what is possible and bring forward a new set of possibilities. Realizing that everything isn’t a remix of something else is as simple as noticing what is unique about any given situation. For instance, where the cynic sees a remix of Bill Clinton’s administration, everyone else sees the first black president. In the end, the word remix gets stuck with the collective disdain felt among those attempting to respond to the present moment who were told they were doomed to repeat the past.

4. Milhouse

As hinted at in part one of this essay, it’s possible that the corniness of the remix is not only attributable to it as a methodology but to the products created from that method, as well. This brings me to the fourth possibility, which is the often gimmicky or insubstantial nature of things that have been remixed. Clement Greenberg defined kitsch as nostalgia for something that never existed. It’s possible that my deeming the word “remix” corny is just another way of saying kitschy, because the cultural products created through remixing often haven’t lived up to that method’s stated bold promises of finality. The idea of a group conversationally re-creating culture without concern for maintaining authorship or claims to property is a novel mode of production, but it’s also necessary to ask what is being produced? Variations of Kanye West, Chuck Norris, Bachelor Frog, something about a cat. These are funny but don’t add up to a Wikipedia-esque level of collective accomplishment. Media scholars take great interest in the ways memes are produced while ignoring or apologizing away the content of the process they are describing. It might be that in order to maintain the scale of participants necessary for ubiquitous creation, remixed memes tend to focus on subjects that are relatably base. There is a fine line between democratic decision making and the lowest common denominator.

5. Progressive Versioning

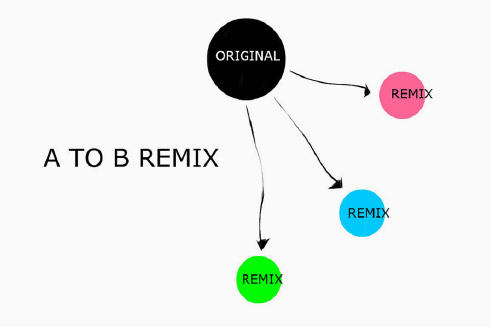

The word remix no longer accurately represents the way some cultural products are made, especially when it comes to online creations. There are now two types of remixes that differ in method and outcome. The first we can call the A-to-B remix. It’s the type I’ve already been talking about. If you take a Willem De Kooning drawing and combine it with Robert Rauschenberg’s eraser, this adds up to Erased De Kooning Drawing from 1953. The finished work of art identifies all participants, their materials, and the chronological relationship between them just as DJ Change’s 2011 dubstep remix of R. Kelly’s song “Ignition” lets you know what the original song was, who changed it, and how that person went about altering it. A-to-B remixing centralizes production around a single creation. “Ignition” could alternately be turned techno, nu-metal, or any other genre. Rather than destabilizing the role of the author or originality, the A-to-B remix emboldens the legitimacy of the original through the attention it was paid when remaking it anew and the expanded audience it gains as a result. It makes sense that the most commonly remixed songs on YouTube are also the most viewed songs on YouTube. The remix is not confrontational; it’s a tribute of fandom, an admission that the first product was so good that it can be dressed up in a seemingly endless number of variants and still maintain its excellence.

But what if the remix were to remove its own footnotes? There is a second type of cultural production taking place that is often called remixing but may deserve a term of its own. To borrow from Oliver Laric, I’ll nickname this type of production progressive versioning. Instead of maintaining a connection to the original, progressive versioning loses touch with where it came from, who it was made by, and when it was made. Progressive versioning is the process Plutarch describes when he asked whether a ship that was restored by replacing all of its wooden parts remained the same ship. Progressive versioning is not about the valorization of the original but about losing all ties to it, about adding to and switching out variables until none of the results bare any resemblance to where they started. This is practiced most efficiently through viewing platforms that necessitate decontextualization for content to gain popularity. Progressive versioning is both a violent and freeing process (the term “creative destruction” comes to mind). By falling off the shoulders of giants, culture is free to travel, to be misunderstood, and ultimately to be reconstituted in unforeseen ways. If the word remix describes a thing that has a beginning, middle, and end, then progressive versioning would differ from the remix in that it has no end and forgets its own beginning. The obsolescence of remixing is setting in because we long for some process of creative production that is more current and able to reflect the time we live in. This turnover is healthy and is created from the same drive for contemporaneity that created the A-to-B remix in the first place.