Lafayette Anticipation associate curator Anna Colin talks to artist Tyler Coburn about Ergonomic Futures, a speculative project engaged with art, design, science, anthropology and writing. In this interview, Coburn discusses the research, production process and network of collaborators of a multilayered project ultimately concerned with the futures of humankind. Anna Colin: When one comes across your museum seats Ergonomic Futures (2016—) in contemporary art exhibitions—and soon in natural history, fine art, and anthropology museums—they look… [read more »]

The History of Non-Art: Part 2

On the Avant-garde as Rearguard

The most groundbreaking art of the 20th century is called avant-garde. But perhaps these pioneering artists were not so pioneering after all. The artistic avant-garde did not break with established genres and traditions so much as it systematically established genres and tradition. Much of what is considered “radical,” “innovative” and “original” about Duchamp and the artistic avant-garde was brought into existence by people who were not visual artists. They were rather what in the art world is known as ”non-artists,” such as journalists, designers, writers, commercial artists and satirists. What is new in the art world is often new only in the art world.

Chapter 2: Backdating Monochrome Painting

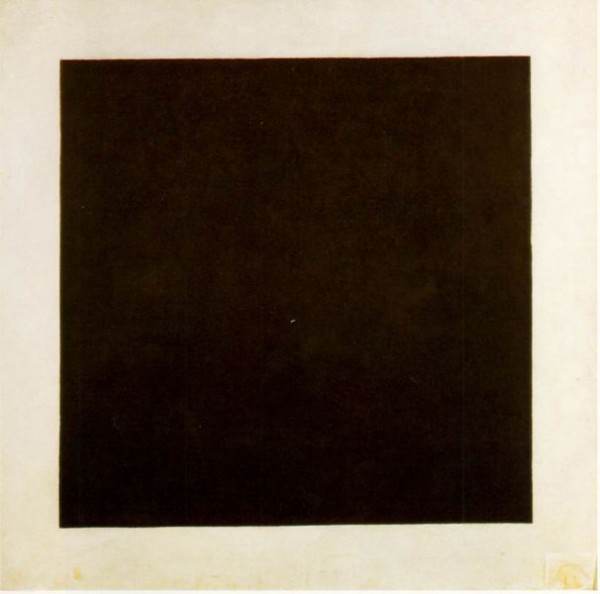

In 1913, the Russian painter Kazimir Malevich (1879-1935) takes an extra look at what exactly he is up to. He does not fancy the painting he is working on, and paints it over with black. This, on the other hand, he likes so much that, as he later recounts, he “couldn’t eat, drink, or sleep” for an entire week. This is all big and new: “Everything we’ve loved, is lost: we are in a desert… Ahead of us there is a black square on a white background!”

Since then, Malevich paints more versions of the “Black Square,” but keeps backdating them to 1913. It is an important moment in art history: Malevich is today celebrated as the originator of the single color painting, The Monochrome.

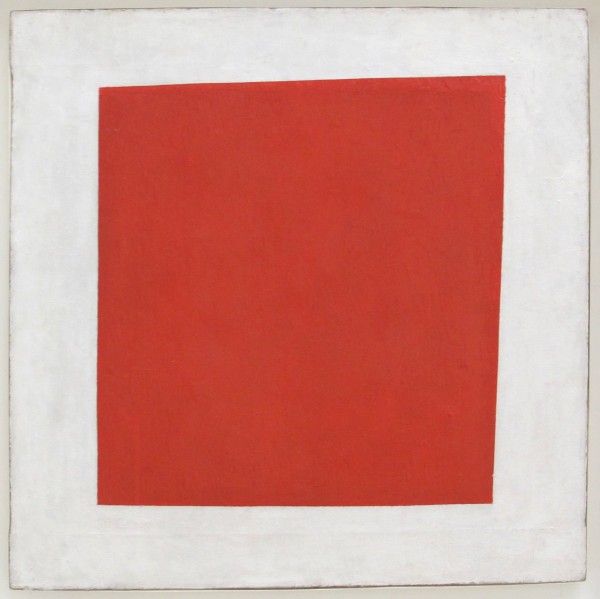

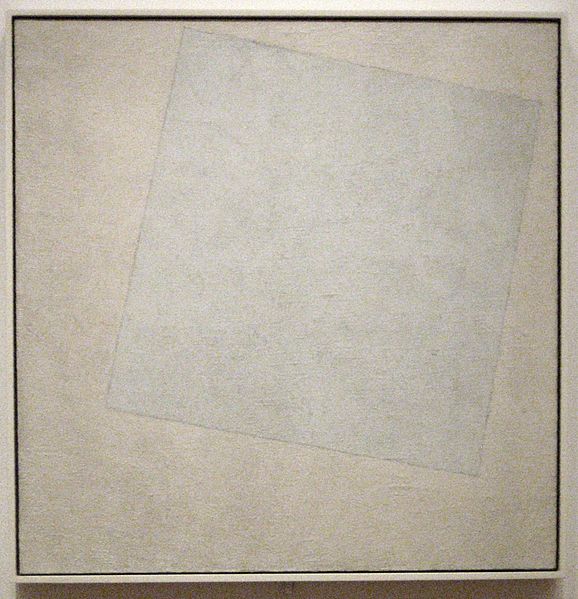

Malevich gets excited, and quickly he is on a roll. Next he paints “Red Square – Painterly Realism of a Peasant Woman in Two Dimensions,” and after that “Suprematist Composition: White on White.” But even if many art historians are now celebrating the 100th anniversary of the monochrome, this is old news.

In the first volume of Laurence Sterne’s novel “The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman” from 1759, the immoderately facetious character, Yorick, dies all too early in the story. A beloved is lost. Sterne marks this tragic turn of events with an illustration, making up a whole page: a black rectangle. It could depict a grave. But this is not painting. Nor are the black monochromes which French caricaturists like Bertall depict in the French press from the 1840s onwards.

What apparently is a painting, however, is the monochrome exhibited in 1851 in Brussels. The painting might have disappeared, but the description of it has not: “The ocean is blue – the sky is blue – and Pandora’s chemise is blue – her blonde hair is blue. And when he has painted her flesh blue, one would think that the artist was blue.”

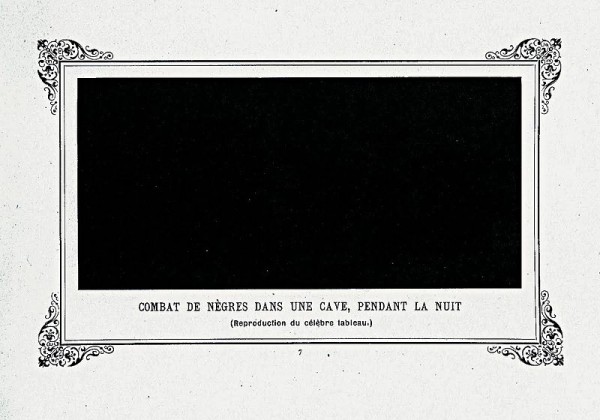

Another early monochrome painting appears in Paris in 1882 at a group exhibition organized by Les Arts Incoherénts. The poet Paul Bilhaud (1854-1933) exhibits a canvas painted black in a golden frame: “Negroes fighting in a tunnel.” His colleague, writer and journalist Alphonse Allais (1854-1905) is so enthused that he subsequently exhibits a white piece of paper with the title “First Communion of Chlorotic Young Girls in Snowy Weather” and a scarlet red piece of fabric named “The Apoplectic Cardinals’ Tomato Harvest by the Red Sea.” Alphonse Allais is on a roll — just like Malevich three decades later. Allais proclaims himself “monochroidal painter.” Later in 1897 he makes a booklet with eight monochromes, “Primo-Aprilesque Album,” which he does not manage to publish the first of April…

Alphonse Allais

First Communion of Chlorotic Young Girls in Snowy Weather, 1897

Based on lost work (1883)

In 1954 another French artist, Yves Klein (1928-1962), launches his great career with a little book “Yves peintures,” which contains 10 monochromes. His colleague Ben Vautier points out that it is somewhat similar to Allais’ album. Klein replies: ”He didn’t follow it through.” Soon after, Klein becomes famous for painting canvases and other stuff blue, so-called International Klein Blue – a color which he goes on to patent.

In New York from around 1950 onwards, many big painters do monochromes. But the battle over the historically most fought-over color, black, continues. Barnett Newman (1905-1970) is convinced he owns it. In 1966, in a letter to the writer Barbara Rose, he complains that she writes an article about Ad Reinhardt’s black paintings “without mentioning my black painting, Abraham, the first and still the only black painting in history.”