Lafayette Anticipation associate curator Anna Colin talks to artist Tyler Coburn about Ergonomic Futures, a speculative project engaged with art, design, science, anthropology and writing. In this interview, Coburn discusses the research, production process and network of collaborators of a multilayered project ultimately concerned with the futures of humankind. Anna Colin: When one comes across your museum seats Ergonomic Futures (2016—) in contemporary art exhibitions—and soon in natural history, fine art, and anthropology museums—they look… [read more »]

The History of Non-Art: Part 1

On the Avant-garde as Rearguard

The most groundbreaking art of the 20th century is called avant-garde. But perhaps these pioneering artists were not so pioneering after all. The artistic avant-garde did not break with established genres and traditions so much as it systematically established genres and tradition. Much of what is considered “radical,” “innovative” and “original” about Duchamp and the artistic avant-garde was brought into existence by people who were not visual artists. They were rather what in the art world is known as ”non-artists,” such as journalists, designers, writers, commercial artists and satirists. What is new in the art world is often new only in the art world.

Chapter 1: The Readymade as Readymade

Precisely 100 years ago, something seemingly irrelevant occurred: “In 1913 I got the joyous idea to mount a bicycle wheel on a stool and watch it spin.” These are the words of French artist Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968). The combination of these two objects is now considered a masterpiece in 20th century art history. Duchamp came up with the term “readymade” because he practically had not made anything; he only put it together. In 1917, Duchamp didn’t even put two things together, but merely signed a urinal with a pseudonym and dubbed it “Fountain.” Since then, his readymades have been interpreted as an attack on painting, on aesthetics, on the art market, on good taste, on art as manual labour and even on the idea of the artist as a genius. And precisely because of this, Duchamp is today celebrated as a genius, as the big mysterious exception that changed the course of art history and anticipated our contemporary conception of art.

When Dada was an Artist

Such flattering terms have never been used for another Frenchman, the author Jules Lévy (1857-1935). In 1882 — that is 30 years prior — something equally exciting happened in his apartment in Paris. But unlike Duchamp’s bright idea, this whole story has disappeared into oblivion. Lévy wakes up with an idea he can’t get out of his head: “An exhibition with drawings made by people who cannot draw.” With the help of friends and colleagues, this exhibition turns into a major attraction. The success is followed up by more ‘free’ exhibitions, now dubbed Les Arts Incohérents. Thousands of people flock to their exhibitions. The press coverage is massive. The participants take the most unlikely names like Dada – also the name of a group of artists that Duchamp many years later socialized with.

In this exhibition, catalogue facts are exchanged with strange information. One exhibitor is “born, but hasn’t yet gotten used to it.” And inside the exhibition the public is asked not to “spit on the ceiling.”

At one of the openings the exhibitors are strolling around with ladders with the inscription “I varnish!” – “Je vernis!” — a pun on vernissage. A flyer for one of the exhibitions is reused as an artwork in another exhibition. Many of these things could have been made today.

The Empty Frame

In Paris, where a painting by Paul Cézanne was also accepted at the official salons of 1882 for the first and last time, Les Arts Incohérents exhibit a cow painted in the colors of the French flag, a sculpture made of Swiss cheese, and a painting of a man whose mouth is penetrated by a collar that is tied around the neck of a rabbit in a cage in front of it. In other words: happenings, installation art, conceptual art, and institutional critique…

Already in the 1880s, this group of writers, illustrators, cartoonists, satirists, journalists, and poster artists practiced most of the ‘new’ genres that are associated with 20th century art.

After a few years, they lose their novelty value. Critique is building. Lévy is forced to admit that Les Arts Incohérents are not art, but rather just fun and games. Duchamp, however, saw things differently. A couple of decades later, he was working as a cartoonist for the exact same newspaper associated with many of these pranksters. But in 1915 he moves to New York, where the locals – in Duchamp’s own words – “took modern art very seriously when it came to America, because they believed that we took ourselves very seriously.”

Back in Paris, people had already seen Les Arts Incohérents exhibit a lot of readymades in 1882. Here they would present things like a frame without content, a stocking — or “bas” in French — nailed to a board and titled “Bas-relief”, a string stretched on a piece of wood and named after the skinny actress Sarah Bernhardt as well as a pair of trousers called “The Eiffel tower.” All of this was something at least Duchamp did not forget.

When Duchamp passes away in an armchair in 1968, the last sound his wife hears escaping his mouth is a giggle. In his hands he is holding a book of one of the most well known of the ‘incoherent artists’, Alphonse Allais.

Anonymous

Bas relief, Stocking nailed to wooden plank, 1882/1988

Reconstruction by Présence Panchounette, Mamco, Genève

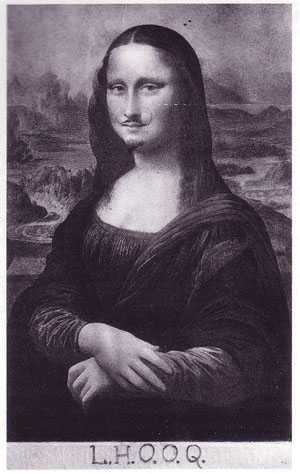

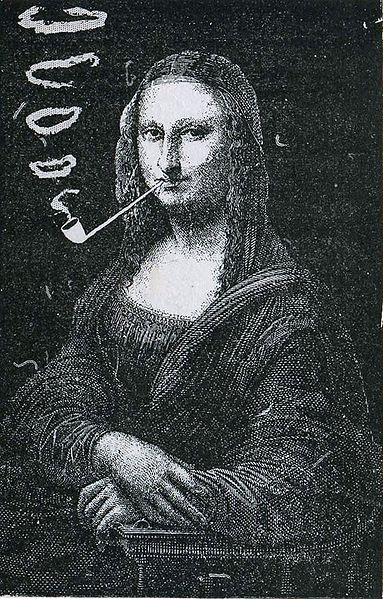

Arthur Sappeckikus alias Sapeck

Illustration from Le rire, 1887

Remake of a work from Les Arts Incoherents, 1883

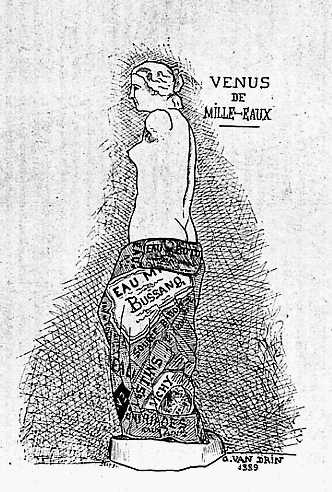

G. Van Drin

La Vénus de mille eaux, Plaster, labels, 1889

Catalogue drawing of a sculpture at Les Arts Incoherents

Toke Lykkeberg is a critic and curator.