Lafayette Anticipation associate curator Anna Colin talks to artist Tyler Coburn about Ergonomic Futures, a speculative project engaged with art, design, science, anthropology and writing. In this interview, Coburn discusses the research, production process and network of collaborators of a multilayered project ultimately concerned with the futures of humankind. Anna Colin: When one comes across your museum seats Ergonomic Futures (2016—) in contemporary art exhibitions—and soon in natural history, fine art, and anthropology museums—they look… [read more »]

Frieze London | Interview with Ian Cheng

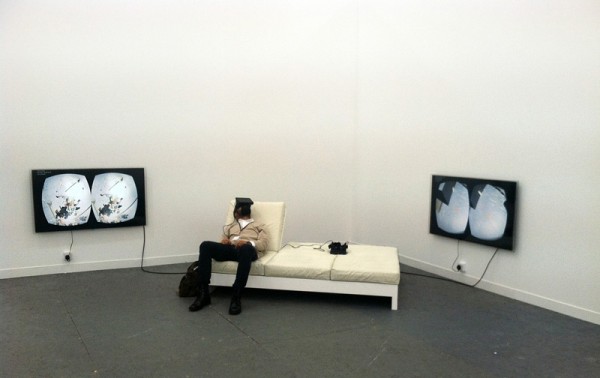

Photo courtesy of Formalist Sidewalk Poetry Club

The annual Frieze London brings together the international heavyweights in the art world and collectors, with 152 galleries showing and selling artwork. At the end of the fair, all pieces should be safely assigned to the many art collectors who come to town to get a (pricey) piece of the cake. The fair takes form as a four-day event in a massive sci-fi tent in Regents Park.

As a DIS representative, I meet up with American digital artist Ian Cheng on VIP Wednesday, the day where all the buying and selling really happens. Cheng looks surprisingly casual when I find him buzzing around his piece at the booth of Formalist Sidewalk Poetry Club, the Miami-based gallery than represents him.

Ian Cheng investigates virtual and spatial forms of material reality, whether it being through 3D stock models or abstract video games. Through 3D goggles, his featured work allows the viewer to enter a trippy, simulated universe with objects flying around that you interact with. Using integrated VR technology in an art context is pretty groundbreaking, and the experience is truly phenomenal. I sat down with Ian in an overcrowded cafeteria-like setting to talk about his piece, Frieze and waking up in virtual reality.

JU: Where does this piece come from?

IC:The piece comes from a body of work I’ve been working on for the last year about live and computer simulations that changes and evolves constantly, potentially forever. They consist of a group of heterogeneous, virtual objects – some I’ve found, some I’ve downloaded, some I’ve ripped from video games – but more importantly what I’ve done is assign behaviors and properties to each of these objects. In a way, it’s about composing with behaviors rather than composing with images and 3d models, which are secondary support to the piece. I’ve found simulation to be an ideal, flexible format and medium to compose behaviors.

JU: So working in the field between science, technology and art, the focus in on creating simulated behaviors?

IC: At this point in history, it’s finally possible to compose behaviors. I’m trying to find a frame that enables you to see what happens when you mash one behavior with another. Artists are always looking for a formula where 1 + 1 = 3; you take concrete plus wood and ideally it becomes something more than the sum of the parts, something third. In the simulations, I’m able to compose human behavior, animal behavior, behavior of inanimate materials like plastic and metal, and observe something which in reality you could never combinatorially experience – I mean, you would probably get arrested if you weld something to a dolphins head?

JU: Probably. Also, you’re composing these behaviors as a total experience in a 3D-world.

IC: Exactly. Up until now, the simulations I’ve made have been seen as a projection where you simply watch a system, but this is the first time where you yourself, in virtual goggles, are inside the simulation. You as a viewer assert influence on the objects, and the objects also influence you. Sometimes objects will follow you and interact with your virtual body.

JU: So it’s a whole new level of interaction?

IC: In a way. It is interactive in terms of influence, but it’s not quite a video game; there’s no goal, there’s no “point” or points. It’s not interactive like new media. The idea is to simply put you, the viewer, in a position where you are one source of influence within the simulation among many influences. Looking at a virtual representation of something, you can feel the materiality of the digital. It’s obviously romantic to say that the digital has materiality, but with these virtual goggles you come closer than on a laptop or TV screen – you know it’s virtual but you feel its physicality. It’s much more intimate. I didn’t anticipate that, but it’s the result.

Actually, when I was installing it I was totally jet-lagged and I fell asleep with the glasses on. I fucking woke up in virtual reality, in this system. It was such a trip!

JU: What did you feel?

IC: I felt like I didn’t have a body and felt I was still dreaming. It looked so dimensional, and I felt inhuman. The idea of composing with behaviors hopefully leads to being able to test the idea what it means to be non-human. We obviously have human impulses, but simulations will hopefully allow more exposure to the mental practice of embodying say someone else’s body, the body of a plant, the body of a virus, of the universe. It sounds almost spiritual. But sometimes you need to take that leap to momentarily get past the bullshit of being a human. Rivalries, power, short-term gain, all these human scale concepts.

JU: Looking at how you’ve installed it (two pair of glasses and flat screen TVs doubling the image of the goggles), what is the significance of the TV? Is that for the person passing by?

IC: The work is in the goggles. I have the TVs because it’s the first time at Frieze where simulation and virtual reality work is being showed. As a casual, super-distracted, maybe slightly conservative passer-by, the TVs would be the hook – the five second bleep that might make you want to Shazam that song, if you know what I mean. They are fishing lines for the work.

JU: Would you say that you have to be more aware of these fishing lines showing at a fair, in comparisons to biennales and solo shows?

IC:Yeah, and particularly at Frieze because everyone is looking for a particular thing, often a physical one. I feel with technology, not just in art, that there’s the first stage where technology is just the pure innovation. But then there’s the second stage, which is just as important, which is the social wrapper– the interface design, the marketing, the terms of use. These are the social realities that make technology relatable and legible to human beings outside the engineers. The reason why new media art is socially ghetto-ized is because there’s an overemphasis on the innovation stage. With the VR goggles, I think we are on the cusp of how they will be socially coded. The Oculus Rift is being targeted for video gamers, but they haven’t fully hit the consumer electronics market yet, so there is a brief window of freedom right now to be able to code VR goggles within contemporary art in a virginal way. In a year’s time, using the goggles in an artwork will have an appropriational coding.

JU: Lets talk about the art fair. It’s a lot more like a market place than a solo show. Do you feel a different energy?

IC: Absolutely, but I also accept that these are the rules of the game. Historically, many artists have rebelliously fought against the institutions and social realities that they were a part of, willingly or not. My fight is not with the institution of Frieze – I chose to be here.

JU: Is it commodifying for you to be here?

IC:I feel like my work is a commodity, that is one of its roles. I think if I was an extroverted person I would naturally turn myself, my identity, into a commodity, but because I’m an introverted person who doesn’t want to be in the spotlight, I prefer my work to be in the spotlight. But on the side of that I feel like I’m trying to push in a direction with concerns that have not yet found the right medium – I’m not even sure I found the right medium in simulation. Nonetheless I feel like I’m pushing in a new direction, and I think that should be valued just like all these paintings and sculptures here at Frieze.

JU: The ways of which digital art is being commodified and sold has been a topic for a few years now. Recently, the first digital auction started as a response to the traditional auction and fair. Do you prefer to push the boundaries within the already established art fair?

IC: Art fairs, auctions, these formats of displaying and selling art … they’re collapsing realities. In 20 years time, I like to think that human beings are intelligent enough to have developed more precise and appropriate platforms for digital art. It feels like skeuomorphism – to fit digital art into the physical auction with the paddles and everything. I think it’s a transitory model. Hopefully someone in that organization is actively thinking about the evolution of the art auction form.

In terms of Frieze: with enough money you can make anything live forever. I’m happy to see it gone, I’m happy to see it stay. Ideally, Frieze as an organism will develop to meet the changing needs of artists, of dealers and art itself.

JU: Best thing about Frieze?

IC: I’m much less of a spatial person in comparison to say sculptors, so I prefer an event rather than a show. I like the event quality that Frieze naturally embodies. I like the ridiculousness of erecting a gigantic air-conditioned, thermo-controlled tent on top of a park for four days. I like the ridiculous effort that has aspired here on the surface of such a fleeting event. People showing and buying here think they are dealing with objects that are permanent, but I think Frieze is a beautiful testimony to fleetingness. A ridiculously expensive testimony, but nonetheless. People feel that energy of the fleeting moment. It’s also a condensation; I’ve met so many friends here, old and new. In art, it’s so rare to bring people together, even for your own exhibition. As a social space, it’s also very functional. In terms of negatives, I don’t think I would be saying anything new. I accept this social reality for what it is.

Ian Cheng is showing at Formalist Sidewalk Poetry Club, F36 at Frieze Frame until Sunday.