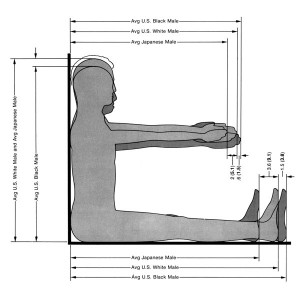

Lafayette Anticipation associate curator Anna Colin talks to artist Tyler Coburn about Ergonomic Futures, a speculative project engaged with art, design, science, anthropology and writing. In this interview, Coburn discusses the research, production process and network of collaborators of a multilayered project ultimately concerned with the futures of humankind. Anna Colin: When one comes across your museum seats Ergonomic Futures (2016—) in contemporary art exhibitions—and soon in natural history, fine art, and anthropology museums—they look… [read more »]

Next-Level Spleen by John Kelsey

FOR MOST ARTISTS TODAY, the laptop and phone have already supplanted the studio as primary sites of production. Early signs of this shift were evident in what became known as relational aesthetics, which, in retrospect, seems wrongly defined as a practice in which communal experience became the medium. It is more properly understood, rather, as a capitalist-realist adaptation of art to the experience economy, obviously, but also to the new productive imperative to go mobile, as a body and a practice. In other words, community declared itself a medium at the very moment that it was laying itself open to displacements it could never survive. Meanwhile, exhibitions were planned on laptops, then dragged and dropped into institutions. Work took a discursive turn, meaning it was now efficiently distributable on a global scale. In the mid-1990s, the figure of the artist, too, seemed to undergo a decisive mutation: The Margiela-clad PowerBook user was more nomadic and adaptive than his antecedents, smoother and more agreeable, better organized and more instantly connected with other members of the burgeoning creative class that had emerged on the front lines of economic deregulation. The contemporary artist now functioned as a sort of lubricant, as both a tourist and a travel agent of art, following the newly liberated flows of capital while seeming always to be just temping within the nonstop tempo of increasingly flexible, dematerialized projects, always just passing through. This was all vaguely political, too, in a Negrist sort of way that promoted the emancipatory possibilities of connection and communication, linking the new speed of culture to the “convivial” spirit of everything relational. The mutation of the artist continued to follow its irrevocable logic until we eventually arrived at the fully wireless, fully precarious, Adderall-enhanced, manic-depressive, post- or hyperrelational figure who is more networked than ever but who presently exhibits signs of panic and disgust with a speed of connection that we can no longer either choose or escape. Hyperrelational aesthetics emerged between 9/11 and the credit crisis and so can be squarely situated in relation to the collapse of the neoliberal economy, or more accurately to the situation of its drawn-out living death, since neoliberalism continues to provide both the cause and the only available cure for its own epic failure.