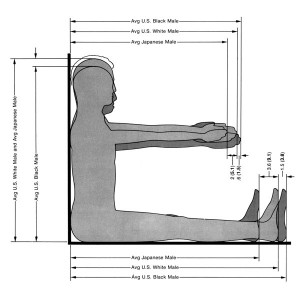

Lafayette Anticipation associate curator Anna Colin talks to artist Tyler Coburn about Ergonomic Futures, a speculative project engaged with art, design, science, anthropology and writing. In this interview, Coburn discusses the research, production process and network of collaborators of a multilayered project ultimately concerned with the futures of humankind. Anna Colin: When one comes across your museum seats Ergonomic Futures (2016—) in contemporary art exhibitions—and soon in natural history, fine art, and anthropology museums—they look… [read more »]

Training for Exploitation? Towards an Alternative Curriculum

Since 2010 we have been organising around issues of free and precarious labour within the education, arts and design sectors. Through our work together, including the making of our Carrot Workers’ Counter-Guide to Internships and carrying out the People’s Tribunal on Precarity , it has become clear to us that we need to engage with the fact that our colleges and universities play a pivotal role in setting up and normalising the regimes of free/precarious labour and life.

In response to this realisation, we began to work towards an alternative curriculum that could be used as a tool by educators and/or students. We invite you to use this resource and to share with us your thoughts and ideas, as well as further links, references or tools that you might be using already so that we can expand this set of resources and share ways of intervening into existing neoliberal educational structures.

We envisage this alternative curriculum to be used in relation to vocational education, internships, professional practice classes, preparation for work experience, internships and other kinds of work-related learning embedded within or encouraged by educational practices. This is particularly pertinent in the current UK context where there are debates about the increasing emphasis on ‘employability’ within education. While we feel that there is nothing wrong with work-based education, the emphasis on employability and increased links with industry can mean the subordination of education to corporate capitalism. While we are not suggesting that students forego work experience, we want to find ways of drawing attention to the issue of the pressures on students to undertake unpaid work as a requirement of academic accreditation and the way educators often encourage students to work for free as the initial step into paid employment. This first installment of an alternative curriculum resource offers tools for critical discussion so that students will be able to develop an ethical code for their own labour and learning.

The position of art and design education as vocational pedagogy is very much based on the idea of art as a calling. This often brings with it an idea of a higher status that is sometimes at odds with how society values artistic production. There are contradictions within this mode of thinking about art and the work of artists: the relationship with ideas of genius and the luxury goods of the art market on the one hand but also cities, such as Berlin for example, striving to cash in on the poor, but sexy, image of the artistic population on the other. In UNESCO’s 1980 Status of the Artist report, an artist is defined as one who considers “artistic creation to be an essential part of their life … and who asks to be recognized as an artist, whether or not they are bound by any relations of employment or association”. Through this idea of vocation, creative labour becomes something that is intrinsic to the artist’s subjectivity and therefore not definable within the terms of wage relations. At the same time, the Bohemian sensibility of free spirited defiance and non-conformity encourages people to reject both traditional working class labour conditions and what might be seen as bourgeois materialism. For cultural workers, more than just food and rent, work is bound up with desires around creativity, ego, authorship and individual performance. These also circulate within the pedagogies of art. In fact often, art school training puts the emphasis on the work coming first over and above everything else including individual subsistence. While this may provide some notion of value of the work produced it can also lead to training in what Andrew Ross has called “sacrificial labour”, creating a space open to self -exploitation. The clichéd view that artists thrive on hardship also conflates the desire for more freedom and choice over work-life composition with a desire for precarious living conditions. It is therefore interesting to think about the role of the art school in producing a subjectivity vulnerable to exploitation and the negative effects of precarity, as well as perhaps producing the ‘dark matter’ as described by Gregory Sholette: the large numbers of ‘failed’ artists who shore up the illusion of meritocracy in the art world.

Within the context of art education, we are particularly interested in looking at its consequences more than its content in terms of its relationship to work and the economy. One of the things we want to do in developing this resource and work towards an alternative curriculum is to address the disconnections between art and design practices, critical theory and professional development. It seems that often students are implicitly expected to turn off their critical and political faculties when they enter a professional practice seminar about copyright, self-marketing and fundraising. Students are often sold a shiny version of freelance work and are provided with tips on how to make it in the creative industries and how to be a professional based on branding, entrepreneurship and the market. This is at odds with the critical theory and experimental practice that they may be also learning as part of an arts course. This kind of professional practice often provides a single model of how to be professional that is not to do with being critical and at the same time does not provide realistic information about the conditions of precarity, employment rights and real work/life in these sectors. At the same time, students’ critical studies may be taught as abstract theory with little connection to their practices and how they might go about making a living. This disconnect is experienced by many as confusing and alienating. But perhaps worse, it replicates a general pattern in academia where politics is often limited to the production of ‘content’ without consequence, content that really ignores the structures and material conditions of its making.

We asked ourselves whether it would be possible to work to re-connect the critical with the practical, whether there might be ways to support other ways of doing culture, not just critique that abandons practice or practice that abandons critique. Given that courses such as professional practice, organising work experience placements and proving the employability of our students are experienced by many of us as staff, we wondered how we would go about it. This led us to the idea of building a shared resourcewe could use to actively intervene into existing art, design and creative industries curricula as a way of dealing with these issues and demands.

We have collected together a bibliography of texts, links to other useful resources, some statistics and teaching tools for use in teaching and learning contexts. We hope these resources will help teachers and students to build their own alternative curricula and encourage students and teachers not to turn their critical brains off when figuring out how to make a living, but instead to develop a critical practice. However, a major concern for us is that there is always a danger that questioning and taking apart the ‘system’ can leave people paralysed and demoralised. It is therefore necessary to also discuss other ways of working, other spaces, economies etc. and perhaps devise practical modes of mutual support before and after graduation.

Some ideas for an alternative curriculum are:

• Investigate alternative historical models that deal with the relationship between education and work, for example that of radical educator Celestin Freinet, who introduced ‘Pedagogy of Work’ or the activities of the Artist Placement Group.

• Discuss different models of survival and subsistence that artists and cultural workers use and the relationship your art practice has to earning a living.

• Integrate discussions on the politics of work and the relationship between art and work during different lessons, tutorials etc., not just as part of a professional practice course.

• Frame work experience/placements/internships as something other than a way into a profession. Support and empower students to have more autonomy when dealing with work placements– preparing students for placements, giving workshops on ethical internships, critically reading the placement/internship descriptions, running through union info on labor rights, ethical contracts, giving information on asking for a fee.

• Encourage work placements or internships as a kind of field-study, workers’ enquiry or Militant Research, “what are the working conditions in the creative industries from your experience – what is desirable about it, what isn’t’?” so that even if students insist on doing an internship/free labor they pay attention to the working conditions.

• Give students the opportunity to critique placements/report back critically on their experiences – organize critical feedback sessions when students return from placement, sharing info with other students who did not do the placements.

*This list is by no means a definitive list and we welcome others to develop their own resources as well as using ours. This is an open invitation to use and build on this pack by both educators and students.