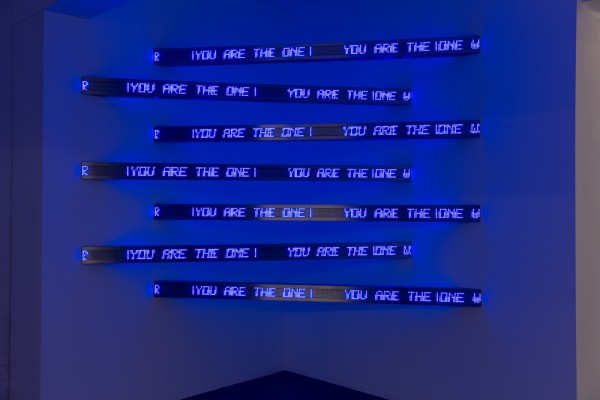

The social conditioning of deaf people constitutes Christine Sun Kim’s inquiry into the anthropogenic definitions of sound. As a sound artist born without the ability to hear, Kim investigates the sonic as a form of capital, and the currencies it formats in social, cultural, and political life. A former artist-in-residency at the Whitney Museum, she has compared American Sign Language and music in TED talks and was featured in MoMA’s Greater New York, cutting through… [read more »]

Ways Of Living ⎮ Arcadia Missa

David Roberts Art Foundation

Curators’ Series #9. Ways of Living (15 Apr – 23 Jul 2016)

Ways of Living, curated by the team behind Arcadia Missa, moves beyond the home as a site of political contestation and into the working place, the artist studio, the public sphere, and nature.

While so-called ‘social practice’ taught us that any attempt of art to engage with issues outside its own institutional reality are easily coopted into the mythologizing machinery of individualism and patriarchy, art still possesses an ability to address issues far beyond the gallery or the museum. Arcadia Missa and its extended family constitutes in itself a proposal of how to organize socially and professionally in a time of cultural austerity and fierce market conditions. – This extends to curating too–– in their Ways of Living they mix their own artist-peers with big art world names from the collection of David Roberts, including Paul Thek and Jenny Holzer (a form of “self-organised nepotism,” they describe it). The notion of ‘community’ must be urgently evaluated as it is relocated and instrumentalized in new contexts, not least in art – and Arcadia Missa is painstakingly aware of this, operating simultaneously in the immediate local area of Peckham, London, as an independent publishing project, and in the international art market. While any community possesses an institutionality in itself, it still serves as a format for organizing and asserting solidarity.

Ways of Living begins by discussing the politics of exhibition-making, in the spirit of institutional critique of the 1970s, but with a reinvigorated, and less antagonistic intonation, focusing instead on spaces of agency and subversion that can exist in a given institutional context. A specially-commissioned graffiti mural by Beatrice Loft Schulz runs along the white-washed walls of the David Roberts Foundation, situated in an old factory. This immediately disrupts the ‘natural’ order embedded into standardized post-industrial gallery spaces: individual(ist) works are suddenly forced into a larger condition of spectatorship and institutional co-habitation, regarding two or three works as one – sometimes creating new harmonies, as when Paul Thek’s trippy Big Bang Paintings seem to become add-ons to Schulz’ expansive composition (leading to a questioning of the power structures behind (art) historical legitimacy). Of course, the gendered definition of ‘artisthood’ and of a ‘work’ is itself a concept that must be reworked, and Eva Hesse’s small, instinctual experimentations in Three from 1965 humbly respond to this. Who gets to do abstract expressionist triptychs in post-war America? 50 years later, Juliana Huxtable’s Untitled (ASSASSINS CREED II) joyfully picks up on discourses of visibility in the arts, literally inserting her friends bodies into codified forms of painterly expression. Hannah Black too manipulates the exhibition space with the instalment of a series of panels painted in a shade that matches her own skin colour (encountering the colour brown in a white cube space is, sadly, still radical in itself). Finally, Adrian Piper’s Metaperformance #1 from 1987 tests the racial constitutions of viewership as she conducts self-aware performances in front of audiences of varying ethnic categorizations.

Living means surviving, working, loving and engaging in dynamics with your surroundings – and art possesses the ability to propose new forms of habitation and use. Lena Tutunjian invites viewers to study her shoplifting abilities in her video work Shoplifting Video that replays the CCTV footage from a small supermarket chain – a study of the performed rules of consumerism and what happens when they are transgressed. Jesse Darling sources their sculptural material from the cracks of society (squats, abandoned spaces) to engage with the socioeconomic meanings and histories embedded in objects – their triptych of windows from a former squat, eroding to reveal many layers of white paint, engages with art history and social politics with equal efficiency.

Holly White’s highly entertaining film work depicts a post-apocalyptic future in which governments let out to tender governmental responsibilities to corporations. In this dystopia, the ubiquitous ice cream brand Baskin Robbins oversees social housing, effectively removing the boundaries between consumerism, human rights and forms of labour. What scenarios might be impending if these discourses are fully drowned in the neoliberal condition of society? Shot with a handheld camera, the piece possesses the authenticity of a home recording or a Youtube documentary, making this satire-like dystopia scarily realistic.

Of course, living means hoping as well, and countering White’s dystopia are Hannah Quinlan and Rosie Hasting’s queer CGI utopias: cinematic landscapes on light boxes that visualise better socio-political conditions at the horizon. An ambient soundtrack mixes mainstream pop music with archive footage from women’s rights debates and discussions – symbolising the messy and ambivalent ground from where we must imagine and build better futures from within the confines of society. Surely, this involves some of the ideas proposed in New Ways of Living.

David Roberts Art Foundation

Curators’ Series #9. Ways of Living (15 Apr – 23 Jul 2016)