DIScuss | Cooper Union Confidential

Will Niebergall, aka Glasspopcorn, is a teenage artist in Tempe, Arizona, looking for a post-secondary art education.

Some of the German idealists, most prominently Hegel, wrote about a theory of “the Absolute,” or that which is simultaneously itself, a distinct thing, as well as everything that could be said to exist in a given universe. They wrote about a couple of concerns with this concept: first, that all human behavior ought to have something to do with “becoming like the Absolute,” or maybe with accounting for one’s position within it. Second, they kind of believed that something like that was impossible, that it was a necessary idea but a deeply flawed one, and no institutions could smoothly assist any person in acquiring knowledge of the Absolute. I only refer to this because I’m trying to pick my way through Hegel at the moment and it’s incredibly difficult and stupid and reminds me of reading articles and blog posts about art world institutions; people seem to be set on this idea of a society deeply involved with and receptive to the work of artists, yet the idea itself is so ill-developed and sparsely discussed that people have vague ideas about what the “right kind” of art institution is. It seems, at this point, like art schools are worth keeping around because of what they do to add to the confidence of young artists and provide a key linking mechanism between young people and the established art world. Art education is pragmatic. To hell with Hegel.

Installation at Like Art Basel, Will Neibergall (2011)

Still, the art institution in general is obviously not free today from relevant criticism. Tom Ellard wrote in a recent blog post, “Artists that constrain themselves are recognized more quickly, they are funded, they are more acceptable to publications because they are easier to digest. They are the cheddar cheese of creativity, and when I am I told that ‘all the best work is happening over here’, I know the place to look is anywhere but there. Innovation is part of a continuing vitality, and confusedly being alive is more important than being neatly dead. We should never ever pre-organize ourselves into categories that fit nicely in museums, journals and repositories. That’s like pinning yourself into a display case.” I think you could say that step one of knowing/caring about the culture of art education in America is limiting severely the range of your receptive capacity for intellectual and creative pursuits, as these institutions are primarily concerned with what is normatively “palatable.”

Step two of knowing/caring about the culture of art education in America: sit atop the apex of western privilege. To take such education seriously is to be already unconcerned with more basic kinds of education as well as the rudimentary means of survival. To be concerned with the institutional conditioning of young artists is to associate oneself with a social group inextricably connected to academic discourse and economic opportunity. I feel like most people know this, but it’s still important to get out of the way.

The administrative office at Cooper Union stands with dim windows like some kind of cave or crevice in the middle of the street, only meters away from the bold facade of 41 Cooper Square, the building in which students study and congregate. The interior is dark and littered with paper and discarded Solo Jazz cups. I visited early on a Wednesday morning with my parents, having planned an interview with an admissions counselor long in advance, though the three or four people in the office seemed surprised to see us. The first person we spoke to, a male counselor, directed me to a small office in which I counted four discarded Solo Jazz cups.

I’ve wanted to go to Cooper Union for years because I’m a young American artist and its most important tradition is free education in New York City. Peter Cooper was on to something special in 1859 when he decided that young artists would probably want to work in New York for free. That aspiration, shared by many of my peers, combined with the entitlement of current students and alumni fueled the outrage in response to the board’s decision in April to begin charging yearly tuition. On May 8, an occupation of the president’s office by current students began in the college’s oldest building as a nod to the college’s founder. An inventor and 1876 presidential candidate, Cooper was essentially a capitalist and a tactful player of the system who chose to use his own privilege to benefit competitive students without the means to receive an elite education in America. Cooper’s philosophy is resonant with many young people today (especially students), which explains in small part the board’s long hesitation to abandon it altogether in favor of a pragmatic and calculative economic philosophy. Because of this tenuous and ongoing transition away from tradition, Cooper Union is already understandably the object of controversy and scrutiny from far and wide.

Before the board’s unfortunate announcement, a few of my friends at home in Tempe, Arizona shared my dream of victoriously fighting through the vigorous and esoteric application process, which includes a dense home test challenging artists to create some of their best work under immense pressure. A few months ago, my friend Julian (who had recently transferred from the public school I attend to a privately operated, art-focused school) texted me asking if I wanted to attend an Arizona “Portfolio Day” mentioning that Cooper representatives would be there reviewing portfolios. I later learned during my interview at the Cooper administrative office that these “Portfolio Days” are put together by a public organization in affiliation with elite art schools like Cooper and they can be eerily clique-y (“Admissions representatives usually have about 60 of the 65 accepted applicants picked out before applications are even sent, so you definitely want to be one of the favorites at the Portfolio Days in your region,” instructed the counselor). After briefly considering the opportunity favorably, I decided that it wouldn’t be worth it due to the commute, not to mention the fact that I basically don’t have a portfolio.

I didn’t acquire my taste for the art world in what seems to be the popular way of doing so, by early exposure to art history and first-hand experience of the work of revered painters and sculptors; while I engage with the history and traditions of art in a serious way now, I was unconcerned with such scholarship just a few short years ago. My first experience of institutional art was a consequence of my internet use, focused heavily on the “new media” of web design, video and digital imagery. When I was twelve years old, my strongest aesthetic persuasion was graphic design, fostered by encounters on Tumblr and my experience of design in the real world. This persuasion accidentally directed me to Internet Archaeology, a website that was maintained at the time by New York artist and designer Ryder Ripps by way of a basic methodology involving the recovery of old animated .gifs from archived GeoCities-era websites. I was fascinated by Internet Archaeology for a reason that was obviously unrelated to nostalgia (too young for GeoCities) and even to the way that graphic design interested me; in the recovered .gifs, I found a connection that I can now only liken to the kind of emotional connection fostered by dedicated engagement with art. After following Ripps’ work for some time, I happened upon his image-based chat website Dump.fm, which directly connected me with artists working in both “new” and “old” media. A collaboration between Dump and DIS made the terminal connection that placed me at the MoMA PS1 in August, 2011, performing rap music with Ryder for an event organized by DIS and filmmaker Ryan Trecartin. I became an artist in an organic and affirming way, through communication with living and dynamic characters rather than the leftover creations of distant personalities. My “new media” orientation and my own interests shaped my talents as an artist, and these are the talents I have to live with today; I’m an awful painter without much sense or vision of the relationship between the tactile experience of creation and the visual consequence. On the other hand, my digital work, my videos and my performances continue to provoke and excite an audience comprised only partially of art world “insiders.”

In Cooper’s office, my counselor seemed unsympathetic to that story. First, he made it known that a sharp student such as I who had let so many Portfolio Days come and go without notice was carelessly letting the possibility of a Cooper Union education slip through his fingers. Second, he briefly expressed some concern with where I come from. I appreciate his sobriety in telling me directly that an institution as elite as Cooper Union is unlikely to recruit at any portfolio events in the southwestern United States when a majority of their successful students come from the east. I am also, in retrospect, grateful that he let me know how disadvantaged I am as a student at a public high school. Finally, I received a simple and effective piece of advice: “Start drawing and painting everyday.” He continued: “The problem with the work I see that concerns pop culture or performance is…how do I know you actually did this? At least drawings and paintings give us something that’s actually there, an indication of the student’s talent.” On digital art: “When we are going through hundreds…thousands of portfolios a day, the likelihood that we are going to spend a few minutes putting a USB drive into a computer is pretty slim.” All of this is valuable information to me, not because it informs my approach to applying but because it has terminally deterred me from doing so in the first place. A Cooper education, which now costs the average student $20,000-30,000 per year, is clearly not available to me.

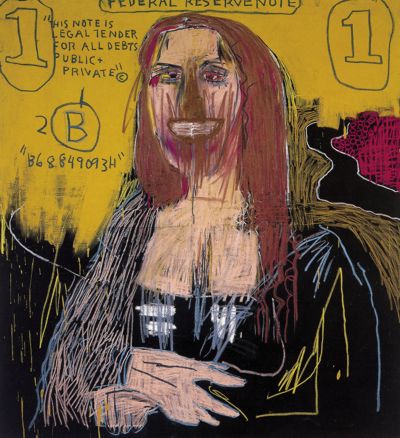

After we left the office, I think my parents could tell I was disappointed and annoyed, but I couldn’t stop thinking about Basquiat. Is that corny? I think the art world has unfairly disavowed his genius, relegating his legend to a tattoo on the back of Rick Ross’ leg. Your Favorite Rapper’s Favorite Painter seems to exist at once as an explosively creative and unique personality in art history as well as a dangerously mythic symbol, representing much more to some people than any one artist ever ought to. The fact of the matter is that Basquiat came from a relatively privileged unit in the comparison class of black families in New York in the middle of the century; his father was reasonably affluent and his mother exposed him to her knowledge of and interest in art history from a young age. We should return to the fact that serious institutional artists rarely come from places and mindsets of true desperation. That said, Basquiat chose to throw much of his privileged life away in favor of an important role in the evolution of American art, dropping out of high school and running away from home to choose the humble means of a bohemian and graffiti artist instead of the affluence promised by his parents and his education. While it’s worth noting that he only took up painting at the suggestion of an older studio renter without much taste for graffiti or experimental music, Basquiat’s paintings have impressed upon western culture with their unique visual style, spoken clearly to art lovers worldwide about the danger of elitist power and value structures in America and taught many art institutions a lesson about unfair and premature judgment of artists as human beings. After I left Cooper, I thought of Jean-Michel Basquiat because he was more interested in art as a dynamic, organic and ongoing event that literally required participants’ physical humility than he was in art as a casual hobby of the privileged, living primarily in museums and books. He was an institutional artist attempting to escape the fate Ellard warned about when he wrote about pinning oneself to a display case. This is chiefly why Basquiat, considered by many critics and historians to be one of America’s best painters, would have absolutely no shot at getting into today’s Cooper Union.

Mona Lisa, Jean-Michel Basquiat (1983)

It would be nothing short of naïve to represent Cooper Union as the world’s central symbol of elitism and inequity in the area of art and art education. As Ellard’s quote above reminds us, the art world is itself a mechanism of exactly that kind of oppression of creativity. But it’s high time that young and developing artists are giving something to hang on to other than the edifice of privilege maintained by organizations of important and almost mythic status in the art world like Cooper Union. The New York art institution doesn’t get a free pass at elitism just because Basquiat happened.

Further, if you hear anyone complaining about Cooper Union in the next year or two, it will almost definitely concern their new tuition policy. That’s important too. Free college is good. But take a moment to entertain the possibility that the awkward publicity surrounding the new policy may not be such a bad thing. In America, when people have to pay more for a product or service than they did previously, every dimension of that product or service usually comes under scrutiny. A few dimensions of the Cooper Union education have been left unexplored in the wake of the tuition controversy; people seem more than willing to accept like some kind of weird, art world version of an a priori belief that Cooper Union is really the best place for art education (probably because of its exclusivity) and the college’s model aside from tuition demands no critical consideration. Nonetheless, people are much more concerned with Cooper now than they were a few months ago, and for an unpleasant reason. If anything, now that Cooper is too expensive for my family to afford anyway, maybe people will find themselves able to accept, even demand fair and open art institutions.

The pragmatist in me (the part repulsed by confusing literature and nebulous dialectical philosophies) knows that we still need places like Cooper, imperfect means of strengthening the bonds that keep the art world from floating away into space. Still, my experience at Cooper Union alienated and offended me. That may not mean a lot coming from a person as privileged as I am, but if art is going to be able to do anything of value in the future (like addressing and dismantling my privilege), there needs to be a new approach.