A Conversation about Ergonomic Futures

Lafayette Anticipation associate curator Anna Colin talks to artist Tyler Coburn about Ergonomic Futures, a speculative project engaged with art, design, science, anthropology and writing. In this interview, Coburn discusses the research, production process and network of collaborators of a multilayered project ultimately concerned with the futures of humankind.

Installation View: Faisons de l’inconnu un allié, organized by Lafayette Anticipation: Fondation d’enterprise Galeries Lafayette, Paris

Anna Colin: When one comes across your museum seats Ergonomic Futures (2016—) in contemporary art exhibitions—and soon in natural history, fine art, and anthropology museums—they look at first glance like quite unassuming objects. But they are in fact the materialization of a much larger research and writing project. Could you talk us through the genesis of Ergonomic Futures and the interests you developed in the context of this project?

Tyler Coburn: This project began with a question: Is it possible, at some point between now and the bitter end of the universe, that our bodies experience such a degree of evolutionary change that the biological, ontological, and legal criteria of the human come undone—when the human fragments or even ceases to exist?

I took this question to a number of people. I spoke with Shara Bailey, a paleoanthropologist at NYU, who said that we’ll only see drastic change if humankind breaks into isolated groups. Owing to their limited scale, the groups would experience low genetic variation, meaning that over generations, recessive traits would have the possibility of becoming prominent. This phenomenon is sometimes known as “the founder effect.”

I talked with a research fellow at Harvard, who works in the lab of geneticist George Church. In 2014, Church claimed to have identified the genes that should be modified to make the human body survive better in “extra-terrestrial environments”: modifications to give us extra-strong bones, lean muscles, and lower cancer risk.

I also wanted to know how a designer would answer this question, so I called Jonathan Olivares, who wrote the 2011 book, A Taxonomy of Office Chairs. Olivares stressed that we need to understand the cultural and sociopolitical context of a given future era when conceiving of how it might be designed.

Seat Detail: Faisons de l’inconnu un allié, organized by Lafayette Anticipation: Fondation d’enterprise Galeries Lafayette, Paris

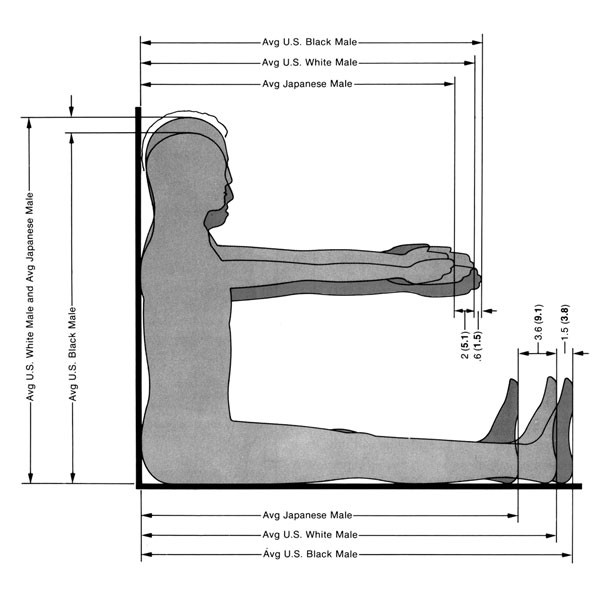

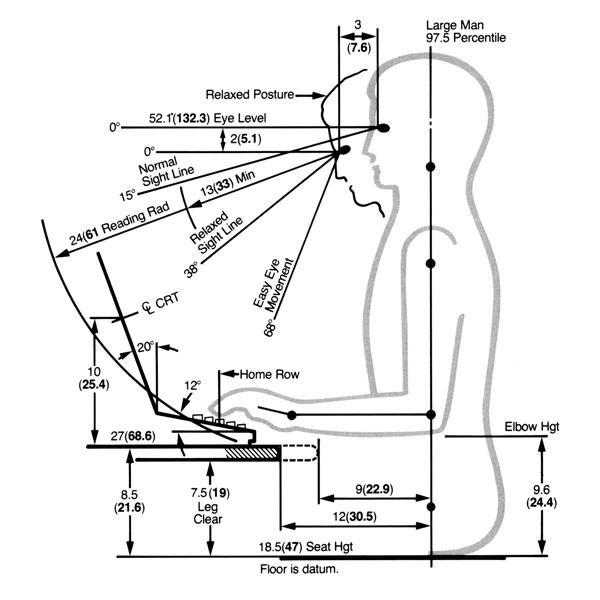

It bears stating that there are two temporalities to my question. While I’m curious about our future evolution, I’m also interested in how this thought experiment might prompt discussion about human typologization and normalization in Western science and social science. I thus began to research what we might call the empirical fictions of the last two-hundred years: the French social statistician Adolphe Quetelet’s model of “l’homme moyen” (“the average man”) from the mid-Nineteenth Century; eugenicist Francis Galton’s subsequent composite photographs, including those of “the criminal type”; and the discipline of ergonomics, which emerged in the Taylorist years and purported to increase the efficiency of the worker, then in the mid-Twentieth Century, shifted focus to enhancing the comfort of our bodies in the workplace and beyond. Ergonomics didn’t limit itself to “the average man”: books from that era include design for the elderly and disabled, for children and the obese—for the standard U.S. male and female bodies of black, white, and Japanese descent. The norms are more granular than those of Quetelet’s time, yet the tendency to typologize remains the same.

Diagram from Humanscale 1/2/3 by Niels Diffrient and Alvin R. Tilley, 1974

AC: How did you get to the seats from this initial set of enquiries, and how did the collaborations and discussions you undertook with designers and producers come to influence the final objects?

TC: The challenge was to give this research material form. I returned to my conversation with Olivares. Ergonomics needs to create body typologies for which to design; while we can all benefit from an ergonomic office chair, for example, there’s an ideal body indexed in its form. What would it mean to exploit this characteristic of the discipline: specifically, to design ergonomic seats for “standard” future bodies, where the qualities of those bodies are indexed in their forms? To project bodily norms into the future—to build seats that render each and every one of us, in the present age, ill-fitting and abnormal—and then invite the contemporary public to sit, to lie, to imagine the bodies for which the seats are intended? Again, this is as much an exercise in tactile speculation as a reflection on how normativity can be articulated through design.

I took my research to New York architects Bureau V, and we collaborated on two seat designs, one of which was commissioned for the 11th Gwangju Biennale, and the other for Faisons de l’inconnu un allié (Joining Forces with the Unknown), organized by Lafayette Anticipation: Fondation d’enterprise Galeries Lafayette in Paris. Bureau V and I agreed that we were not making models of future seating, but seats that could function both now and in the future. If our human were to come along in 10,000 year’s time, the seat would be there to accommodate her. (I’m winking through my keyboard.)

This meant that material durability was a huge consideration. With the Paris seats, for example, we took the excellent advice of Dirk Meylaerts, the Production Director at Lafayette Anticipation, to employ Soft-Touch: a rubber-like finish commonly used by the aeronautics industry. For Gwangju, we employed a composite wood veneer made from scraps of fast-growing hardwoods. The wood grain of this veneer is an absolute fiction—an illustration of what wood might look like. It’s thus a fitting material for one possible future, when wood is a scarce resource, yet remains desirable for design.

AC: I find interesting that a transdisciplinary enquiry such as this can give rise to both a highly material and functional object, and a freeform online publishing project. Could you talk about the narrative component of Ergonomic Futures and the website you have conceived for it?

Diagram from Humanscale 1/2/3 by Niels Diffrient and Alvin R. Tilley, 1974

TC: Writing is a big part of my practice, and in most projects, it finds a way of angling in. With Ergonomic Futures, I wanted to make my research available to people using the seats, so decided that a website would be the ideal format. Reading on a handheld device is a tactile experience, which I see to be coextensive with the tactile engagement that my seats invite.

On your recommendation, I began collaborating with designers Luke Gould and Afonso Martins on the site. Structurally, the departure point was the “Great Chain of Being,” which has an interesting provenance. It began as an imagined weapon used by mutinous gods in The Iliad, and by the Elizabethan Age, became a metaphor for divine order: the object in which everything had a link and a place. My website forgoes this determinism, repurposing the chain for an informal congress of the academics, the case studies, and the other characters who populate my research.

Vitrine at the Seodaemun Museul of Natural History, Seoul

AC: Going back to the seats, they are presented in contemporary art settings before entering the realm of the museum. You previously talked about how working with art institutions merely served to enable this second, most important finality to happen. Could you elaborate on the meaning of Ergonomic Futures’s eventual siting in museums of anthropology, natural history, and fine art?

There’s a basic protocol: in a given city, we make two identical seats destined for long-term life, respectively, in a fine art and a natural history or anthropology museum. The primary reason for this is that Ergonomic Futures draws on disciplines pertinent to both types of institutions; by siting an identical seat in each context, the public will have the opportunity to find it framed by the different disciplines and by markedly different exhibitionary contexts. One of the Paris seats, for instance, will find a home in the newly renovated Musée de l’Homme (Museum of Man)—aptly, in a section at the end of the permanent display, entitled “L’Homme évolue encore” (Man continues to evolve). A Korean seat will go to the Seodaemun Museum of Natural History in Seoul, occupying a spot near a hysterical vitrine where the standard “evolutionary march” ends with the skeletons of a human and monkey embracing!

With this protocol, I’m also taking advantage of the temporality of these museums, which are indebted to the 19th Century heritage model. Such institutions wed a commitment to preservation with the promise of timelessness: their holdings (no matter the restoration required to keep them perfectly embalmed) will survive forevermore. In a practical sense, this is great for my project! How few places exist in the world that offer the certitude, the conviction of eternal life. So in a sense, I’m not donating furniture to museums so much as stowing seats in contexts best suited to preserve them—to ensure that they’ll still be kicking when the right bodies eventually come along to use them…

Installation View: The 11th Gwangju Biennale, curated by Maria Lind

AC: The website is connected to the seats in the viewing space, via a QR code or similar technology, but the seats are absent from www.ergonomicfutures.com. Does the website function as an independent publishing platform that could possibly expand, or simply survive—paralleling the wear and movements of the seats in the museum? Do you have as much faith in the future of the internet as you do in that of the museum?

TC: I want the website to have a quasi-autonomous life within this project, partly because it’s written for a general readership, not just for the people actually using my seats. And indeed, there’s an expansive, evolutionary horizon to the writing. The site takes form as a series of stories I wrote, linked together in a chain. The topics are many and varied. One story traces telepathy from experiments conducted in the 1930s, by Upton Sinclair and J.B. Rhine, to current telepathy-like technologies that allow thoughts to move avatar arms. Another revisits a 1960 NASA research proposal for a human capable of living in “space qua natura.” In essence, this entailed constant drug infusions and regulation by exogenous devices—not a pretty fate for this imagined being, whom the researchers called a “cyborg.” Some claim that this was the first time in history when the term was used. Still another story looks at instances of human chimerism, which often occurs when fused eggs are inseminated. The child born from such circumstances has multiple DNA signatures, effectively making her multiple people. My story looks at the case of one chimera, Lydia Fairchild, whom the state determined was both the mother and aunt of her children.

Design-wise, these stories can have multiple versions, and every tier of the site can change over time. New stories and versions may appear; existing ones may be edited or deleted. The font has a similarly open horizon. Gould has typeset the site in OSP Foundry’s Libertinage, an open source font comprising twenty-seven variations of Linux Libertine. These variations are applied at random to new stories and versions, evolving the site textually as well as visually.

Those are the evolutionary conceits. Survival is another matter. Martins lent his expertise to designing a site that’s fairly resilient to the internet and its vicissitudes. For example, we decided to forgo any external links; as surrounding websites fade into obscurity, ours won’t be riddled with broken links. Nonetheless, the internet is of a far different stripe than a heritage museum: a fantasy of totality belying an imperfect archive. Perhaps the best hope my site has is to become something like its evolutionary precedent, the “Great Chain of Being.” Perhaps, for future viewers, it will survive as a weathered testament to the worlds of old epistemologies—and to the futures conceived from one generation to the next.

Seat Detail: The 11th Gwangju Biennale, curated by Maria Lind