On the Avant-garde as Rearguard The most groundbreaking art of the 20th century is called avant-garde. But perhaps these pioneering artists were not so pioneering after all. The artistic avant-garde did not break with established genres and traditions so much as it systematically established genres and tradition. Much of what is considered “radical,” “innovative” and “original” about Duchamp and the artistic avant-garde was brought into existence by people who were not visual artists. They were… [read more »]

The History of Non-Art: Part 4

On the Avant-garde as Rearguard

The most groundbreaking art of the 20th century is called avant-garde. But perhaps these pioneering artists were not so pioneering after all. The artistic avant-garde did not break with established genres and traditions so much as it systematically established genres and tradition. Much of what is considered “radical,” “innovative” and “original” about Duchamp and the artistic avant-garde was brought into existence by people who were not visual artists. They were rather what in the art world is known as “non-artists,” such as journalists, designers, writers, commercial artists and satirists. What is new in the art world is often new only in the art world.

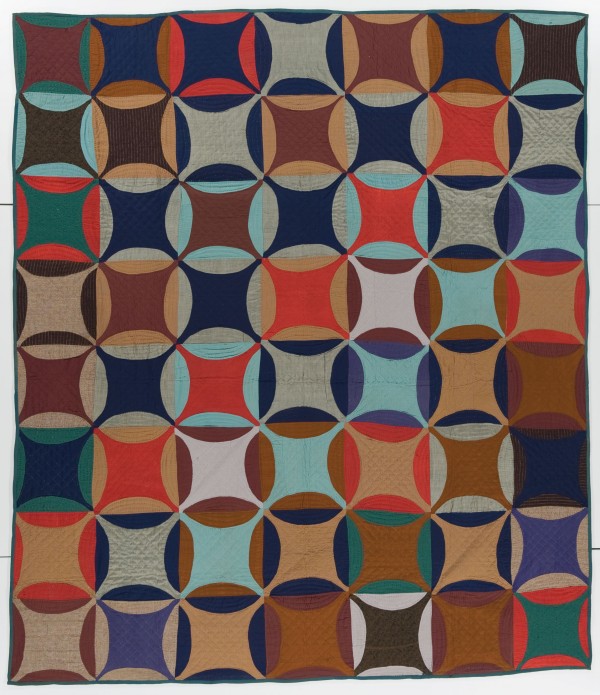

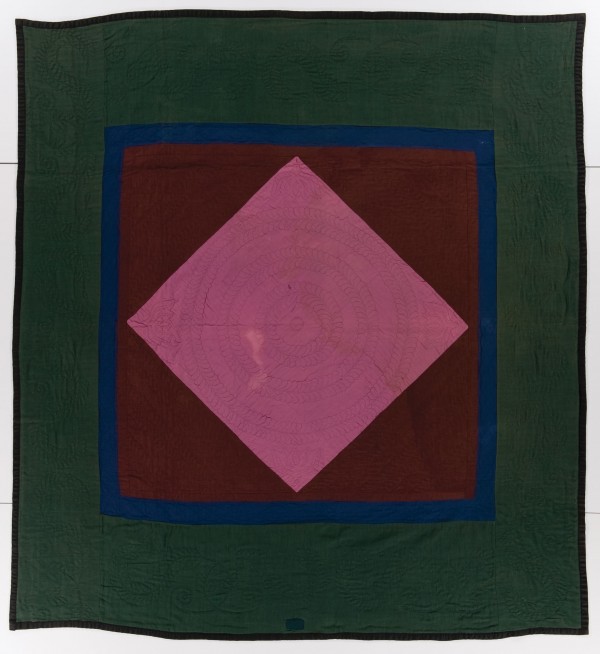

Anonymous/Amish, Crib quilt, Kansas, 1920-30, Collection of Faith and Stephen Brown

Chapter 4: Amish Minimalism

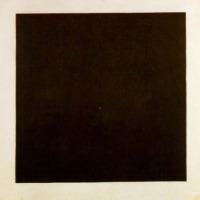

At the end of the 1950’s, an American in his early 20s, takes an extra look at what exactly he is up to. He does not fancy the painting he is working on and paints it over with black. This, on the other hand, he likes – much like his role model Kazimir Malevich, who had a similar revelation half a century earlier.

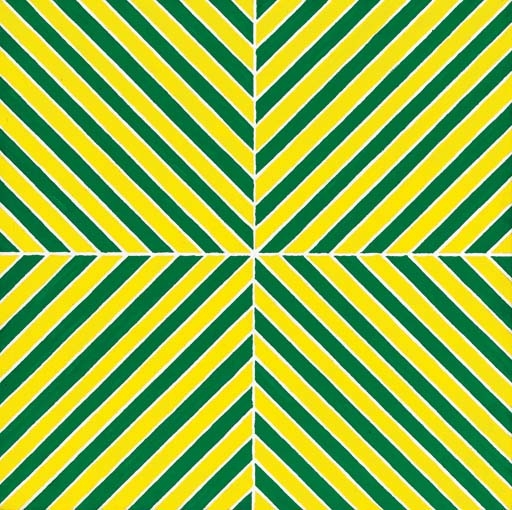

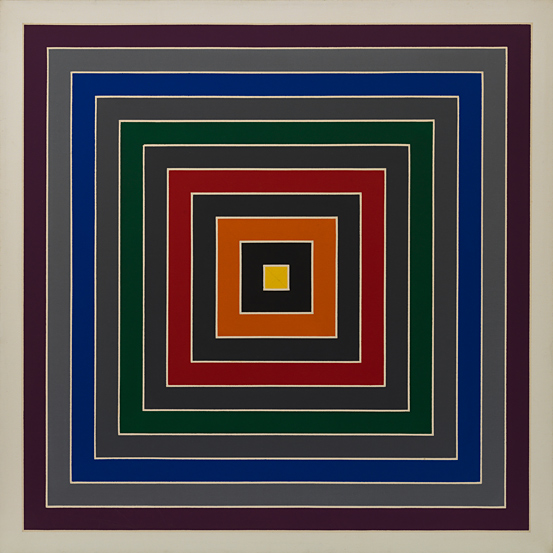

Frank Stella, Fez, 1964, Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo

Frank Stella, Fez (2), 1964, MoMA, New York

The name is Frank Stella. Already in 1959 at the age of 23, he exhibits his black paintings with tight geometric patterns at MoMA in New York. In 1970, the museum gives him his first full-scale retrospective as the youngest artist ever. Stella thinks that abstraction is the last thing painting has to offer the world.

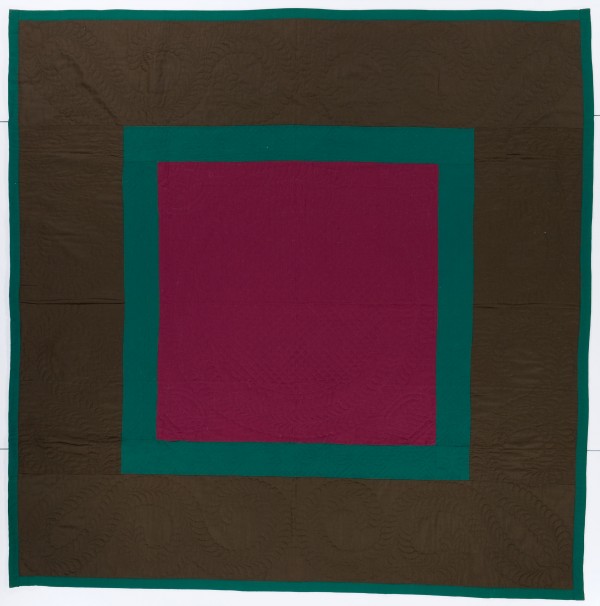

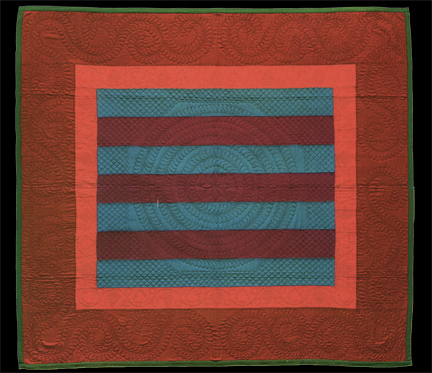

Anonymous/Amish, Pennsylvania, 1930-50, International Quilt Study Center & Museum, Nebraska

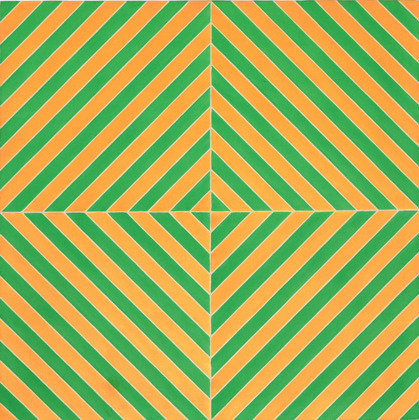

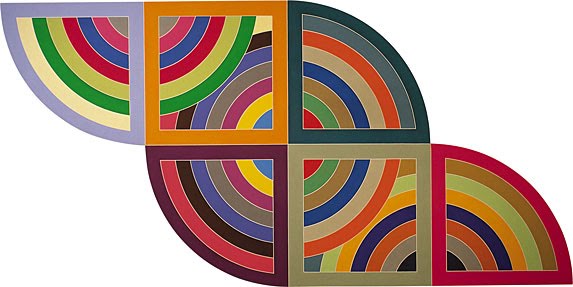

Frank Stella, Harran II, 1967, Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York

According to MoMA, Stella is first and foremost an “innovator”. His tight paintings, which later light up in stark colors, are fresh. They are seen as a break with the dominant taste of the day, American Abstract Expressionism. There is nothing touchy-feely about Stella’s painting. No bombast. In 1964 he infamously states: “What you see is what you see.” Stella is cool and today referred to as one of those who paved the way for minimalism. One of the most important minimal artists, Sol LeWitt, also known as a conceptual artist, sums up the ideal of the time: “The idea becomes a machine that makes art.”

Finally American

America is not just the new world. New York also beats Paris as the new capital for art. Artists and critics are preoccupied by the advent of distinctly American art. During the cold war, the CIA even pushes the new painting as the imagery of the free world. And with Stella and his colleagues, the USA finally seems to have gotten its own short art history of movements overturning movements – as in Europe, when the new art was said to spring from there.

Anonymous/Amish, Robbing Peter to Pay Paul, prob. Pennsylvania, ca. 1880, International Quilt Study Center & Museum, Nebraska

Frank Stella, Tahkt-I-Sulayman Variation II, 1969, Minneapolis Institute of Arts, Minnesota

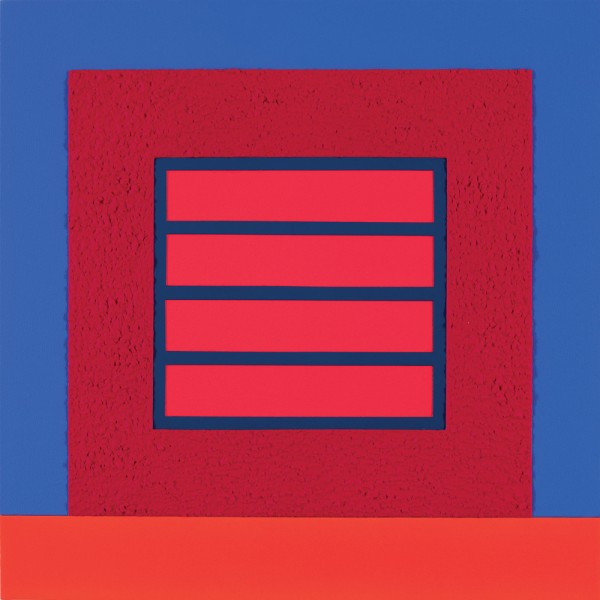

But while some see minimalism as breaking with Abstract Expressionism, other observers in the 1960’s see the new art as prolonging older American folk art traditions. Especially the parallel to Amish quilts from their golden age between 1880 and 1940 is so obvious that Whitney Museum consecrates a whole exhibition to displaying the quilts in 1971. It is the first time the Whitney shows anything other than painting and sculpture.

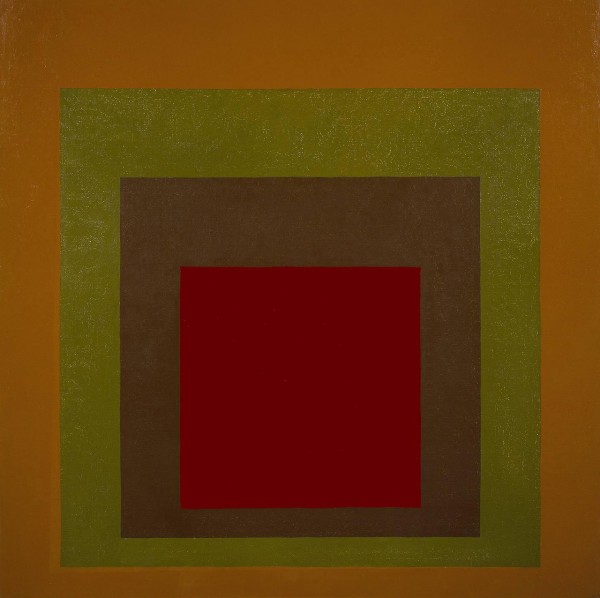

The art insiders, who see the Amish quilts, find that the exhibition looks like a group show of American painting from the last couple of decades. The quilts recall anything from Mark Rothko to Sol LeWitt. They recall the German immigrant Josef Albers whose wife Anni Albers, a famous textile designer, is well-versed in various folk art traditions. The quilts are even reminiscent of the Hungarian artist Victor Vasarely’s optical paintings, which the new American painters however brush off as uninteresting European art. In the 1990’s, art historian Robert Hughes, an Australian settled in the States, concludes that Amish quilts are no less than “America’s first major abstract art.”

Anonymous/Amish, Crib/doll quilt, prob. Pennsylvania, ca. 1910-30, International Quilt Study Center & Museum, Nebraska

Frank Stella, Gray Scramble, 1968–69, Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York

Amish at Broadway

While the painters in the 1960’s talk about new painting, others confuse their works with quilts fabricated by the Amish. It is odd. In so many ways, the two phenomena might at first come off as irreconcilable. Whereas Stella gets into automotive paint, the Amish’ austere off-spring of Protestantism holds autonomous art and most of the modern world, cars included, at bay. However, it is definitely hard to overlook the overlaps in mood, sensibility, composition and color palette. What the Amish did in Lancaster County is pretty close to what would later be trending in New York’s art world about 150 miles away. The popular musical Plain and Fancy testifies to the increasing traffic between the two worlds. The story about a New York couple, who is won over by Amish life in Lancaster County, premieres on Broadway in 1955 and runs for over a year before touring around the states.

Anonymous/Amish, Center Square, prob. Pennsylvania, ca. 1910-30, International Quilt Study Center & Museum, Nebraska

Josef Albers, Homage to the square: Gained, 1959

One can, of course, readily imagine differences in conversational topics within the two communities, one mainly constituted by male painters, the other mainly by female quilters. Nonetheless, they follow similar aesthetic guidelines: A marked skepticism towards representing the world, towards illusionism and the expressive self-realization of the individual.

Barnett Newman is one of the great painters who backs the show at the Whitney as the quintessence of American creativity. But he also rules out any talk of artistic inspiration.

The debate about the status of Amish quilts is still alive today. Is it art? And when is inspiration inspiration? This question is also raised in the 1940’s in a different context at a moment, when Jackson Pollock’s works are being compared to those of Native Americans, whom he and other painters are excited about. Pollock explains that the kinship “wasn’t intentional” but probably “the result of early memories and enthusiasms.”

Anonymous/Amish, Quilt, Pennsylvania, ca. 1890-1910, International Quilt Study Center & Museum, Nebraska

Mark Rothko, No. 37/No. 19 (Slate Blue and Brown on Plum), 1958, MoMA, New York

Anonymous/Amish

Crib/doll quilt, prob. Ohio, ca. 1900-20, International Quilt Study Center & Museum, Nebraska

Mark Rothko, Light Red Over Black, 1957, Tate, London

Folk in art

In the 1950’s, word has it that Andy Warhol is rummaging antique boutiques on 2nd Avenue for “folk art.” He finds that it confirms his aesthetic sensibility. In the 1960’s more American artists get into folk art. Donald Judd’s interest in the Shakers is well known, but already in the 1950’s, before Stella’s breakthrough, Robert Rauschenberg creates a stir in New York. In 1955, he breaks with the canvas, replacing it with a quilt atop a sheet and a pillow. This so-called “combine”, one of his first, is presumably his own bed turned 90 degrees and hung on the wall. Maybe he has the quilt from his mother, a dedicated quilter, underneath whose quilts Rauschenberg had fun memories playing around as a kid. His mother was also the one who introduced him to collage.

Louise Lawler, Freud’s Shirt, 2001/2003, Edition of 100

Robert Rauschenberg, Bed, 1955, MoMA, New York

Rauschenberg’s importance for American art is hard to underestimate. But maybe the same goes for quilts and, in particular, the Amish. However, the quilts’ connection to modern art might have found its best articulation in the words of the quilt historian Robert Shaw: “Amish quilts come from a place, which Modern artists seek to find.”

Rebecca Zook, Bars, c. 1910, Pennsylvania, Collection of Faith and Stephen Brown

Peter Halley, Red Prison, 2012, Courtesy Patricia Low Contemporary

Toke Lykkeberg is a critic and curator.