How the Umbrella ‘Revolution’ meme hurt the movement in Hong Kong

Jason Li is a Hong Kong based designer and consultant. He primarily works with tech companies and startups in Asia. With An Xiao Mina he co-founded The Civic Beat, where people discuss using technology for social and political change.

Here, he weighs in on how the #UmbrellaRevolution hashtag and Internet memes both helped and hindered the recent protest movement to emerge out of Hong Kong.

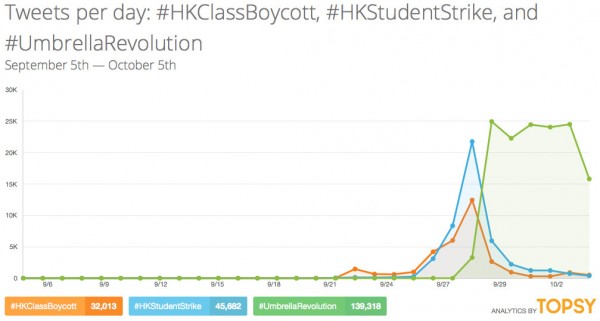

The ongoing protests for democracy in Hong Kong have been dubbed by many as the “Umbrella Revolution.” But days before the term was created, the dominant internet meme supporting the protests was built around student selfies accompanied by hashtags #HKClassBoycott and #HKStudentStrike. This was in line with what was then a students-only protest. Supporters participated by finding a photo of themselves as a child, often in their student uniform, and posting a picture of it to Instagram and Facebook. Some participants chose to decorate their photos with a yellow ribbon for democracy as well.

“Umbrella Revolution” only appeared in the media after local police forces unleashed a barrage of tear gas and pepper spray on protesters last Sunday. Unarmed citizens defended themselves with nothing but surgical face masks, science-class goggles and ordinary umbrellas. Shortly after the clash, stunning photos of protesters holding up their umbrellas amidst a sea of tear gas spread like wildfire across the internet and the term “Umbrella Revolution” was coined.

Unfortunately, the word “revolution” has extremist connotations that do not help but hinder the protest. To begin with, calling it a revolution is simply inaccurate: people are asking not for overthrow of the Hong Kong government, or of China, but for a more representative government. To add to that, CUHK Professor Wong Hung believes that it gives Beijing the wrong idea and encourages them to crack down on the protesters. Pro-establishment politicians Tam Yiu-chung and Robert Chow have also used the term on TV and in interviews to paint a stereotype of out-of-touch, extremist protesters. In that way, while the visual imagery of the Umbrella Revolution is uplifting for most people, its name has sparked unnecessary controversy and internet memes are to blame.

After the events of Sunday when non-students also joined the fray, the umbrella very quickly became the dominant visual. By the time I woke up Monday morning, the press, led by the BBC, had already cemented the popularity of #UmbrellaRevolution as the dominant hashtag, and the internet memes followed.

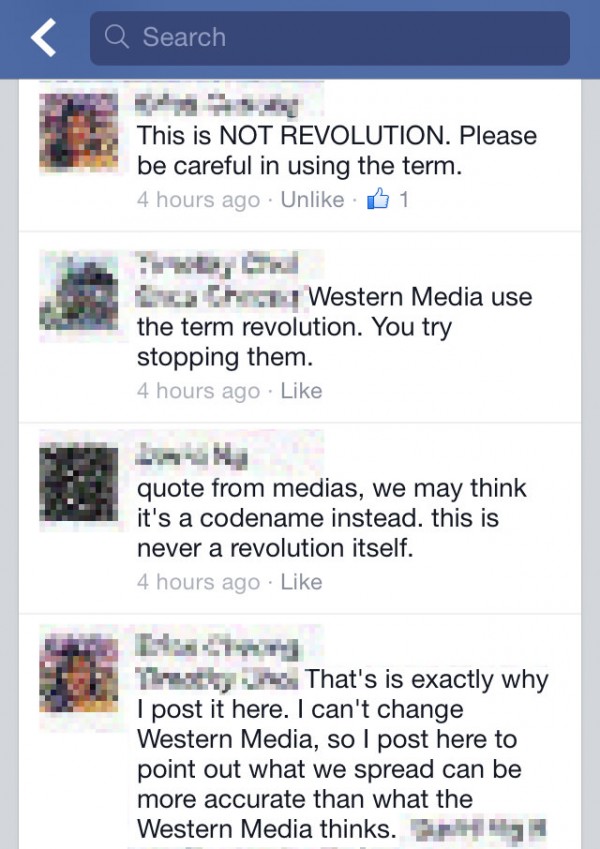

During this time, the term “revolution” was met with some on-the-ground resistance. Given the lack of survey data, I only have anecdotal evidence to support this claim:

@krislc I really oppose to the use of the term revolution though

— J. L. Carvalho (@luxlus) September 29, 2014

.@krislc I think the term "revolution" is intentionally used to strike fear in the heart of Beijing.

— Aureliano Buendía (@Aureliano_no_24) September 29, 2014

@chopkickpunch I dont like #UmbrellaRevolution coz its not revolution yet

— Kris Cheng (@krislc) September 29, 2014

@chopkickpunch #UmbrellaRevolution started by BBC and became a hit though. #OccupyHK is good

— Kris Cheng (@krislc) September 29, 2014

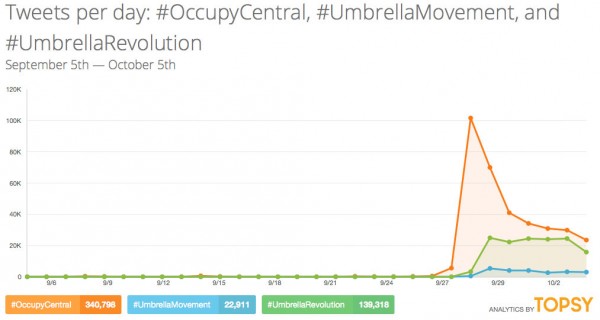

To be perfectly clear, #OccupyCentral was and remains the most popular hashtag. But it doesn’t lend itself to a visual treatment the way #UmbrellaRevolution did. Additionally, #UmbrellaMovement itself never took off, at least in English.

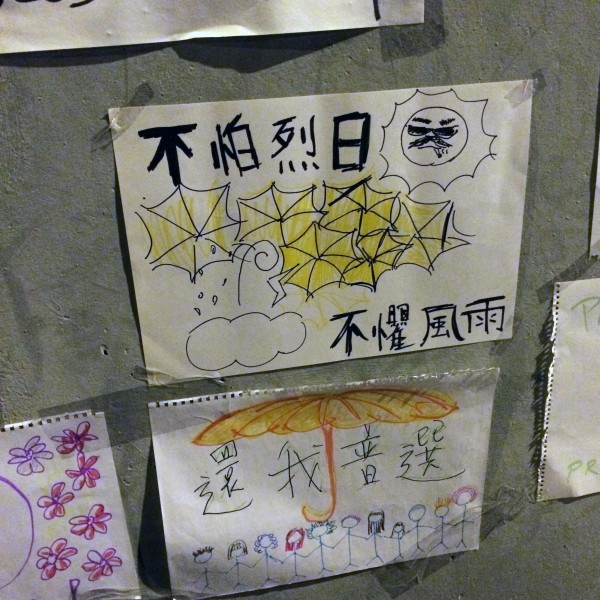

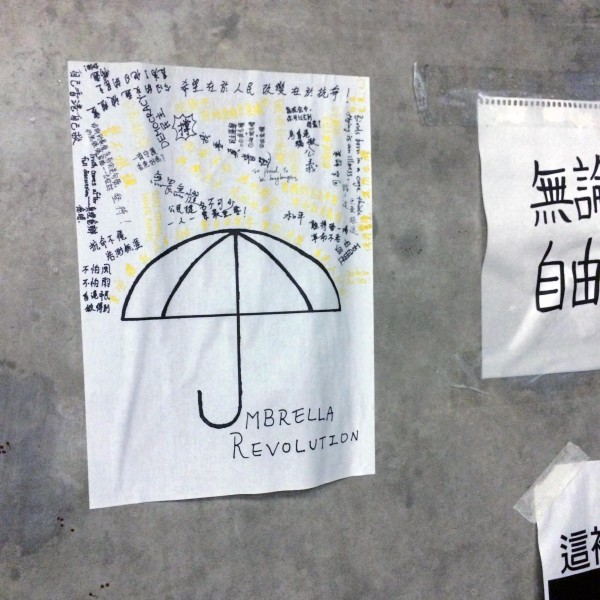

Because the umbrella is such an easily drawn, easily shared visual symbol, it quickly made its way across the internet. People who could not make it to the protest, whether if it was because they were abroad or had to stay home to take care of kids, phoned in with illustrations of the so-called “Umbrella Revolution.”

During the earlier part of the week, my colleagues and I at The Civic Beat collected over a hundred umbrella memes before giving up after we realized that hundreds more were to come from a widely-shared Facebook design competition, a Facebook group and at least one Tumblr devoted to the same task.

My theory is that these umbrella images became so popular on the internet that they made their way into the protest itself. Most protesters were constantly on their cell phones and, despite rumors, the internet connection was never cut during the protest. So it’s easy to see how symbols and messages on the internet might have influenced what protesters thought.

Unfortunately, the “revolution” moniker also made its way into many umbrella images, as if imposed from above. Protesters may have also noticed that the international press paid attention to the “Umbrella Revolution,” and borrowed the term to spread the word further.

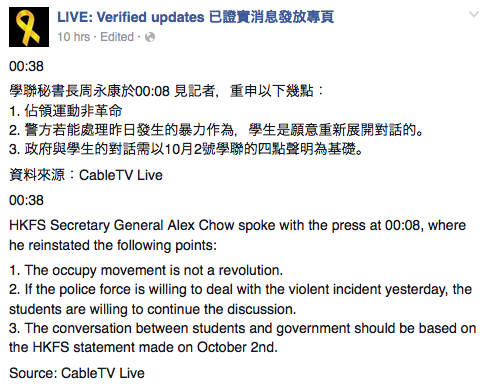

This is where internet memes and foreign media headlines of the “Umbrella Revolution” (currently the cover of Time in Asia) clashed with the interests of many protesters, including that of the leading organizations:

HKFS: #OccupyHongkong is NOT revolution, it's a democratic movement, we heard there'll be violent clearance tonite, will stay alert

— Occupy Central 和平佔中 (@OCLPHK) October 4, 2014

Internet memes and the foreign press may be at fault for coining the “revolution” moniker, but they have also been instrumental in making the movement as successful as it is now. Early on in the protests, internet memes helped build public awareness by allowing people to silently show their support by posting an image or changing their profile picture. (Many profile pictures on Facebook have become variations of the yellow ribbon for democracy.) The foreign press plays an even bigger role, in both creating avenues for public debate as well as fulfilling their role as a watchdog for malpractice. So while the internet public and foreign press have been overwhelmingly-positive influences, it’s also due time for them to reflect on the power they wield.

This article originally appeared on Jason Li’s blog 88 bar on October 4th.

Edited by Graham Webster and Ada.

Follow Jason Li