#millennialsovereignty #rollupthepartition

Keywords: beyonce, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, cultural conundrum, dan perjovschi, Goldsmiths, jon lucas, Klein Blue, madeline o'moore, Marianne Franklin, matthew grumbach, Néstor García Canclini, partition, Peter J. Hutchings, vince patti

Should Beyoncé be Dan Perjovschi's celebrity confidante?

December 13, 2013

Don’t talk to me today unless it’s about @Beyoncé THANX –Katy Perry

Out of all the accolades Beyoncé earned over the course of 2014, perhaps the most intriguing praise came from Facebook COO Sheryl Sandberg, who penned the short feature that accompanied the singer’s Time “100 Most Influential People” cover spread. The tribute was fitting and not for the reasons one might expect. Sandberg was particularly delighted that the album announcement took place under her sphere of influence, on Facebook and Instagram. The communiqué was a message from businesswoman to businesswoman: thank you for using our platforms to unveil your secret digital release.

During the weeks and months that followed, no Beyoncé lyric or gesticulation went unnoticed by her hordes of fans, often resurfacing on Facebook and Instagram to a cacophony of approval. The album was destined to be a hit, but no one could have anticipated that it would become a meme-generating tour de force. The widespread acclaim characterized a year that unfolded in the singer’s shadow, cast in Beyoncé pink. The precise hue, hexadecimal color code #ffbed6, typifies the pervasiveness of the Beyoncé brand, which colored popular culture, online and off, with a veneer of consensus.

If International Klein Blue is liberating, #ffbed6 is benumbing. It camouflages the tenuousness of the loose affinities we develop online; meanwhile, a number of hostile conditions persist behind the pink façade. One of the most receptive commentators attune to the transnational conflicts that disrupt contemporary connected life is the Romanian artist Dan Perjovschi. Having worked as a newspaper illustrator, his practice encompasses political drawings and text, produced with a remarkable speed that rivals the pace of Internet memes. Conflating Perjovschi’s political consciousness and the figuration of Beyoncé, the “Partition” meme is a middlebrow attempt to parse social media interconnectedness as an ideology, a set of principles that predicates the evisceration of borders prematurely. As cyberspace is beset with oblique divisions, we are obliged to harness Beyoncé’s popularity and the familiarity of the meme form to disseminate a message of discord.

When Dan Perjovschi completed “WHAT HAPPENENED TO US?” at the MoMA in May 2007, New York City was at his feet. He had spent the past two weeks on industrial construction lifts, drawing on the museum’s massive atrium walls above curious crowds of visitors. The exhibition occurred not a moment too soon, following the completion of the Yoshio Taniguchi redesign in 2004, when the museum was beset with growing pains. For many people, the colossal proportions of the central atrium represented the crux of the institution’s renovation woes. Luckily, audiences responded favorably and the New York Times art critic Roberta Smith later praised Perjovschi’s installation for helping revive the otherwise “chilly” atrium.

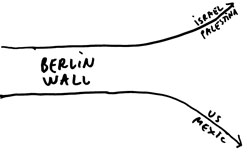

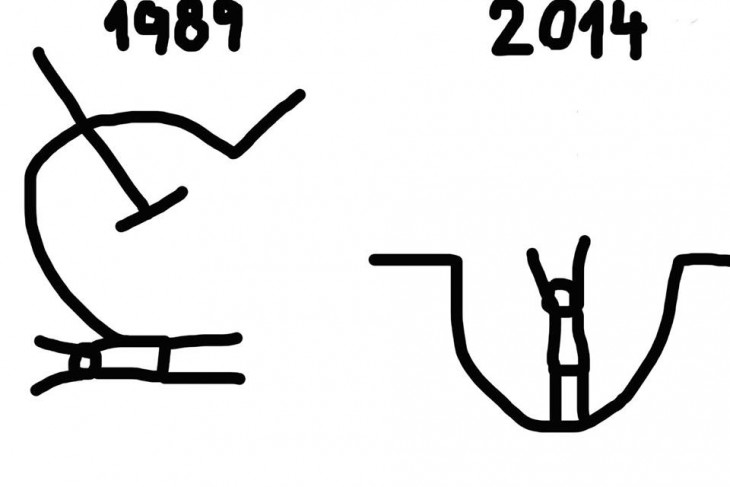

The artist’s terse, sometimes humorous political drawings are patterned on contemporary mass media. Extracting stories from the news and current events, Perjovschi told one interviewer during the show’s run, “I try to narrow an idea which is like the logo of the topic, not exactly the particular case.” Rendered in logo form, the drawings often reach the heart of socio-political matters more perceptively than traditional media outlets and the academy itself. The production time is fast and the simple snapshots of current events often take on a life of their own. Cultural scholar Peter J. Hutchings recalls that one drawing consummated with striking simplicity an idea had begun developing for a journal article. It depicted the “horizontal bifurcation” of the Berlin Wall into two endless contemporary fragments, the West Bank barrier wall and U.S.-Mexico border fence. The image ends up propelling Hutchings’ multifaceted comparison in the final article, titled “Mural Sovereignty: From the Twin Towers to the Twin Walls.1”

Dan Perjovschi: the wall, 2007, ink on paper. Courtesy the artist and Gregor Podnar Gallery Lubljana-Berlin and Lombard Freid Projects

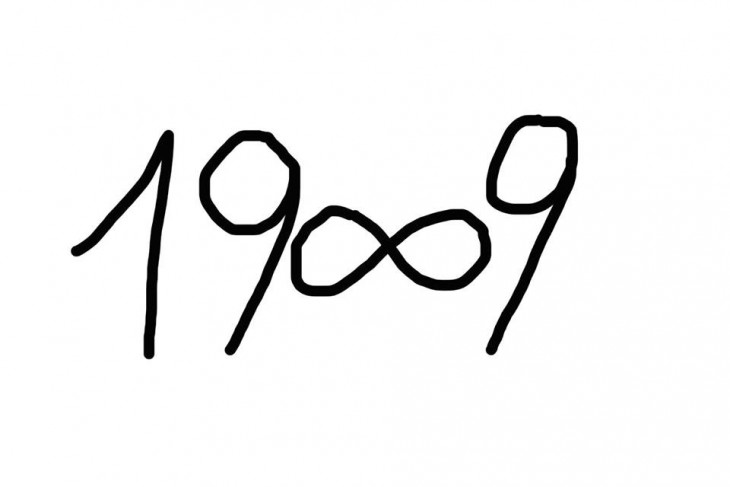

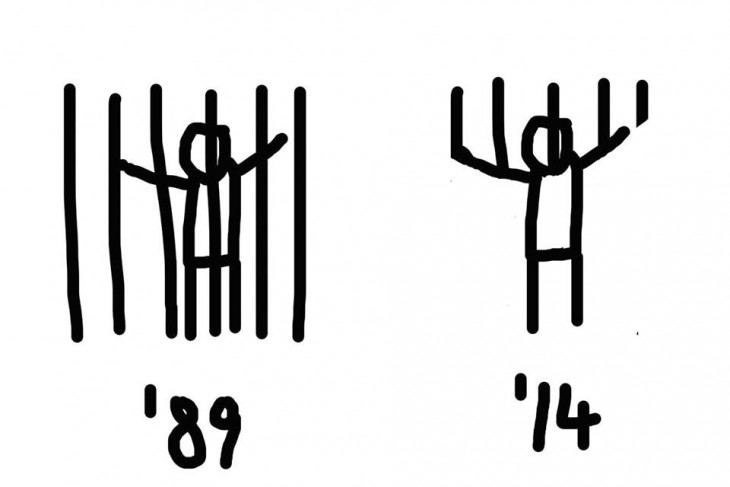

The text navigates three historic dates: the fall of the Berlin Wall on November 9, 1989, the groundbreaking for the West Bank barrier wall on June 16, 2002, and the ratification of the Secure Fence Act on October 26, 2006. Building upon a debate that enlivened geographers in the late 1990s, Hutchings enumerates why post-Cold War optimism belies “the paradoxical reappearance of ancient territorializing strategies in postmodernity.” While stylistically and historically sound, Hutchings’ tripartite view is missing an important contemporary moment, December 13, 2013, the day Beyoncé broke the Internet par excellence. She was not named Facebook’s U.S. entertainer of the year for no reason. Her album drop and the ensuing jubilation brought people together, if only superficially. Succeeding post-Cold War optimism, the Beyoncé euphoria gave way to a new era of misguided hopefulness.

Courtesy of Dan Perjovschi’s Facebook

As a point of induction, December 13, 2013 inaugurated a year in which territorial barriers were breached, commemorated, and reconfigured. Operation Protective Edge, the 25th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall, and President Obama’s executive actions on immigration all constitute part of this saga and so does “Partition.” According to Vogue, the song’s music video precipitated “the era of the big booty,” a period when any given day a celebrity butt would surreptitiously appear on your news feed. “Mural Sovereignty” speaks to the implications of misreading history, dislodging all hope that the demolition of the Berlin Wall catalyzed the inception of a new era of human mobility. What it does not take into account is the signification of borders and the barrier apparatus for a public who enjoys the self-aggrandizing consensus culture and “silent populism” of global networked communities online. Borrowing a phrase from Néstor García Canclini, it remains to be seen whether social media’s “game of echoes” obfuscates the proliferation of barriers to our detriment.

Courtesy of Dan Perjovschi’s Facebook page

The result is a conundrum where we feel closer than we actually are, irrespective of the barriers we have not yet purged. It is the predicament of “millennial sovereignty” and it is a confounding state of affairs, one compounded by our use of social media. Goldsmiths professor Marianne Franklin ascribes the perplexity to cognitive dissonance; there is a difference between Internet in popular mythology and the Internet as lived. “The Internet, as it has developed so far, is the quintessential signifier of a particular understanding and set of practices that comprise global interconnectedness even if the latter in terms of operation are deficient, inefficient, and hugely uneven in distribution or degrees of compatibility between regions, groups, or individuals,” she explains. Notwithstanding trolling activities, social media provokes a false confidence in our capabilities to connect, in no small part due to the affirmative structure of many platforms. Likes are reassuring, yes, but they are not inherently transcendent. A critical mass of solidarity does not entail actionable changes on the ground, where people still face militarized barriers and limitations on their movement.

Courtesy of Dan Perjovschi’s Facebook

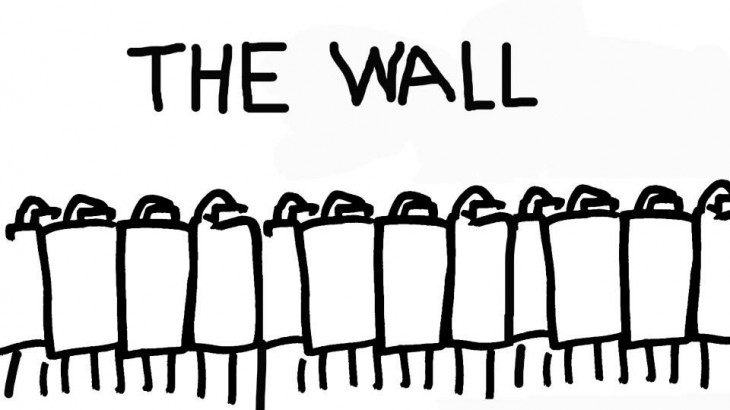

Arjun Appadurai had called for the theorization of “fantasies (or nightmares) of electronic propinquity” in 1996’s Modernity at Large, though the discordant quality of interconnectedness remains largely unheeded. One point of contention concerns the propagation of socially mediated walls online. Walls are the sites where we traffic our news and form supranational bonds. As a conduit for disseminating media, they are an indelible part of Internet infrastructure. Attuned to these formations, Dan Perjovschi extended his practice to the Facebook wall as early as 2011. At first, he merely uploaded photographs of his installations, creating albums that pertained to commissioned projects at institutions like the Dublin Contemporary and the Museo Universitario Arte Contemporáneo in Mexico City. Supplementing the project-based albums, Perjovschi began scanning and uploading individual drawings directly to Facebook, mindful of their memetic potential to occupy the same space as Rebecca Black, planking, and the Honey Badger. More recently, he has bypassed the analog drawings all together in favor of digital drawings, which he uploads en masse.

Courtesy of Dan Perjovschi’s Facebook

The digital drawings are timely critiques, covering topics ranging from the protests in Hong Kong to Valdimir Putin and Ukraine. Yet, the reception is often paltry; most images do not generate more than ten likes. That’s not to say the work is second-rate. It’s just a confusing format. The digital drawings invoke the rhetoric of online activism and the familiar wit of meme culture in one fell swoop. Regardless of popularity, Perjovschi suffuses the meme form with the fissures of contemporary life, an important task given what’s at stake. According to Marianne Franklin, “Physical border controls in ‘meatspace’ are increasingly being matched by cybernetic ones in cyberspace and those enforcing these emerging barriers—real and imagined—are not just classical state-actors.” Millennial sovereignty is also a tipping point. The very platforms that stoke our “fantasies of electronic propinquity,” Facebook and Google, also erect new barriers by seizing and stockpiling intellectual property. The question then becomes how do we respond to and disrupt these antagonistic configurations without completely renouncing our allegiance to those virtual citizenries. As a project of consciousness-raising, Perjovschi’s digital drawings offer a visual tool to dissociate from the affirmative daze that festers on social media platforms.

Courtesy of Dan Perjovschi’s Facebook

Geographer Ash Amin’s far-reaching consideration of the mutability of territorial boundaries imparts some insight here. In “Spatialities of Globalization” he notes, “Little concession is made to the possibility traditional forms of demarcations between spatial and territorial forms of organization might be blurring or moving like a line in shifting sand.” At first glance, Dan Perjovschi seems like our perfect Facebook redeemer-in-residence. In terms of his practice, he has exhibited the ability to acclimate to shifts in the sand. He can “move fast and with stable infra.” What he makes up for in agility, he lacks in reach. Ultimately, his deficiencies allude to a crucial factor: Perjovschi is in desperate need of celebrity confidante.

Beyoncé, 2014 MTV Video Music Awards

Marina Abramović and Jeff Koons have Lady Gaga, but Dan Perjovschi needs Beyoncé. He cannot induce the kind of paradigm shift we need to lay bare millennial sovereignty, certainly not with 5,530 likes. From sampling Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s TED talk speech in “Flawless” to illuminating the stage with the word ‘feminist’ during her MTV VMA performance, Beyoncé’s cursory flirtations with activism pair well with Perjovschi’s logo renderings of current events. Fused together in a cohesive meme, roll up the partition is a call to arms that exploits social media channels of transmission. The collaborative meme is familiar in form and content, which conceals its subversive purpose. The dissemination of the “Partition” meme represents the tacit reeducation of interconnectedness as we know it. Each share erects a new barrier that refutes hyperconnectivity while simultaneously making use of it. Rolling up the partition is really about refocusing the conversation. It’s a discussion about what we can’t do together, not what we can do.

1Hutchings, Peter J. “Mural Sovereignty: From the Twin Towers to the Twin Walls.” Law and Critique 20.2 (2009): 133-146.

Design and Images Vince Patti

Web Development Madeline O’Moore and Jon Lucas