Monegraph and the Status of the Art Object

Keywords: Adriana Ramić, algorithms, Art, art market, Bitcoin, blockchain, data, data issue, Discussion, electric objects, Kevin McCoy, machine learning, Mike Pepi, monegraph, morgan sutherland, net art, Saul Ostrow, Software, Zoë Salditch

A roundtable discussion with six artists, writers, and entrepreneurs on art and tech.

Monegraph and the Status of the Art Object

On Monday February 10, 2015, just as The Data Issue launched, Morgan Sutherland gathered six artists, writers, and entrepreneurs positioned at the intersection of the art market and the tech industry to discuss the potential of Monegraph, the fledgling platform that emerged from Rhizome’s Seven on Seven in 2014. The brainchild of Anil Dash and Kevin McCoy, it promises to harness the distributed potential of the blockchain (the technology behind Bitcoin) in service of digital artists. Organized around questions of the role of new platforms and their impact on the circulation of the art object, the spirited discussion ran for several hours, tackling the nature of the digital art object, its market, and its status as a locus of cultural inquiry.

Below is a series of edited excerpts from the recorded conversation.

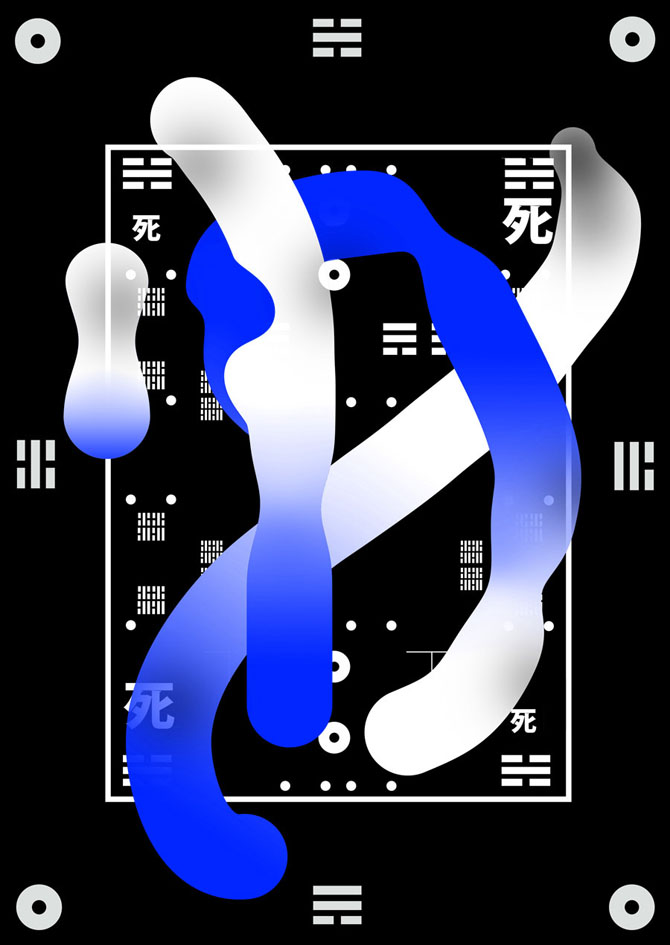

Adriana Ramić, The Return Trip is Never the Same (After Trajets de Fourmis et Retours au Nid, Victor Cornetz, 1910), 2014

Steven Sacks: I’m founder and director of bitforms gallery. bitforms started about 13 years with a specific focus on new media, more experimental based work, a lot of it of course connected to technology, new processes in creative development. It was important for us to cover a range of how new media is defined, a larger umbrella than just one generation.

We’ve worked hard at having different generations who, in my opinion, interpret a variety of what new media can be. We were in Chelsea for 13 years and we recently moved to the Lower East Side, which is very exciting.

Kevin McCoy: I’m an artist. My artwork is produced in collaboration with my wife Jennifer. For a long time we’ve been doing work that intersects with technology, broadly speaking. I’m also a professor in the art department at NYU. I oversee the digital practices in the art department. In May of last year I presented a concept called Monegraph at Rhizome Seven on Seven at the New Museum and since that time, I have slowly been working to develop it as a platform.

Zoë Salditch: I’m cofounder and director of artist relations at Electric Objects, a startup based in New York City. We’ve created an integrated computer and screen that you hang on your wall so you can display art from the iInternet in your home. Before that, I worked at Rhizome for many years. I’ve worked with artists at the intersection of art and technology from a non-profit perspective for a while, and now I’m doing business.

Adriana Ramić: I’m an artist. I live and work in New York City. Most recently I’ve participated in exhibitions at the Kunsthalle Wien and Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain, Paris, and will be giving a lecture next month at the University of the Arts Helsinki. My last project was a digital document drawing from century-old ant pathways, predictive text, and machine translation.

Saul Ostrow: I’m a critic and curator. I founded Critical Practices Inc. We have 4 core programs. One is that every 5 weeks we invite artists install work here, in this space. Every 5 weeks we also invite 30 people for a different conversation on different topics. We publish a broadsheet called LEF(t), and we’re now launching a CPInPrint where we’ll be publishing small books. None of the materials we produce get posted on the web.

Zoë: What’s the motivation behind that?

Saul: For one, not to contribute to the glut of content. Also in terms of the publication, while the texts can be published on the web, the artists’ projects in LEF(t) can’t because they’re 22 x 28 inches and not everyone has that format screen. In terms of the round table discussions, they are about being present, although we do transcripts when we can afford to and audio recordings of them. These get distributed to the people who participate. In terms of the artists’ works, what gets posted to the web is whatever the artist wants.

Mike Pepi: I’m an art writer interested in the intersections of all of the above. I’m editing, along with Marvin Jordan, the DIS Data Issue. This discussion is a core part of the themes at work in the Data Issue—when Morgan and I were talking about possible contribution, we began by discussing the “first wave” of these digital arts tech startups, (art.sy, Paddle 8, artspace.com) which are obviously private and mostly for-profit . These basically are attempting to introduce efficiencies into the market by organizing information, to cut out the asymmetrical structure that fuels the art market, and yet they are still wary of going “all in” and replacing the primary organs of the art system.

There is also a kind of a second wave of arts/tech platforms, which I think Monegraph and Electric Objects fit into. I’m glad to have the blockchain be the focus throughout this conversation. I think that’s potentially one of the more transformative ways of approaching “provenance” in the traditional sense. This directly addresses something that many of the other online platforms are “beating around the bush”, so to speak. Monegraph, in theory, becomes an interesting point of departure for this conversation—it’s quite new, technically, and yet it raises all of these questions that have been with us forever .

Prompt

Morgan Sutherland: The digital object called a “file,” and in fact the entire desktop operating system, is based on a metaphor of how traditional paper-based offices operated. The objects within this metaphor are designed and designated as representations of real objects. Forty-five years after the birth of this metaphor, we’re more likely to think of a digital print as a representation of a digital file, when the digital file was originally conceived of a as a representation of the printed document. Art, however, has doggedly maintained the primacy of an auratic power of the original object and it seems we find ourselves only now trying to represent certain aspects of art objects and their relations digitally within the expanded space of the networked desktop. Given the arbitrary space of possibilities afforded by computation, is it not somewhat absurd to uncritically reproduce the conditions of physical objects rather than attempting to imagine new logics of thingness, ownership, exchange, etc. more faithful to the affordances of the medium? What does it mean to establish notions of provenance for objects that elude exclusive possession? Is this a contradiction, a natural progression, or a step along the way to unforeseen future states of affairs?

Bitcoin is based on a physically distributed ledger, or database, which nobody owns or controls, that records monetary transactions. The underlying technology that enables this is a blockchain. So fundamentally, it avoids the problem of a single owner, or a single actor having control. One project, Ethereum, takes this concept to the next level. They’re producing, and will release shortly, a platform that allows you not only to create a currency based on this technology, but to create any kind of program which operates in a distributed space.

Meanwhile, beyond Bitcoin, which was the first widely-adopted blockchain implementation, there are numerous projects implementing their own blockchains or repurposing the Bitcoin blockchain to various monetary and nonmonetary ends. Monegraph I believe uses the Bitcoin or the Namecoin blockchain?

Kevin: It’s officially blockchain agnostic, but the initial prototype used the Namecoin blockchain.

Morgan: I mention Ethereum to point to the possibility of distributed applications beyond the sort of distributed storage offered by Bitcoin and other blockchains. Ethereum refers to these distributed applications as “contracts.” A common example they use is escrow: a certain quantity of digital currency is held by a “contract” and is released upon certain conditions being met, i.e. two people agreeing that a transaction has gone according to plan.

There’s an interesting history of contracts pertaining to the ownership and transfer of artworks, from Seth Sieglaub and Bob Projansky’s “The Artist’s Reserved Rights Transfer and Sale Agreement” to Rafaël Rozendaal’s “Art Website Sales Contract”, but the possibility for distributed, programmatic contracts could expand this space dramatically.

Discussion

Morgan: With that said, Kevin, do you want to give a short description of Monegraph?

Kevin: Monegraph, as it was presented in May at Seven On Seven, has a story leading up to it: I had been interested in and exploring Bitcoin for a long time, beginning in 2010, and had moved on, but in 2012 Brad Troemel was doing his MFA thesis at NYU, all about Bitcoin and The Silk Road. He was taking my seminar “Anarchy and Imagination” also at that time and our conversations about Bitcoin was an occasion for re-entry into that scene.

Diving back into this next wave of it in the end of 2012/2013 and seeing it in an in-depth way was really interesting. The technology and information theory component of it was really interesting, the culture, the community, the online manifestations. Especially then. It was incredible, and bizarre, and amazing, and odd … a recreation of the larger financial world in these weird micro-niches, with economic models proliferating beyond any regulation: stock markets, people issuing bonds using Google Docs to track ownership, homemade derivatives. Money was going around all over the world, it was really wild.

It’s a very political and ideological community. Very anarchistic and libertarian, various ideologies were coming together. I kept coming back to the idea of the blockchain, of the public ledger as kind of data commons, as a database that nobody controlled in a direct sense. That was unique. It wasn’t just a database, but it was a transaction mechanism that had a conception of value. There was scarcity to it. It meant this weird contradictory possibility of ubiquity and scarcity at the same time through these cryptographic techniques of public/private key encryption. There was a public component and a private component and, because of that, there’s data that is scarce and unique and transferrable. The fact that it’s scarce and transferrable is the underlying aspect of the value proposition that Bitcoin makes – that it has value because of those functions.

I was thinking of the different uses and what kinds of public records would be useful to put there. I started talking to people about the idea of using the blockchain as a digital asset registry, allowing artists to register ownership of their work. But the Bitcoin community had really no interest at all. So I began telling people in the art world about it, eventually talking to Heather & Michael at Rhizome. In February 2014, they invited me to Seven on Seven with Anil Dash, who had also been talking to them about the blockchain. In May, when we got together in the same room for the first time, I said “let’s make a digital art asset registry.” We came up with a way in which it could happen and on stage at the public presentation, we enacted the steps of registering and transferring ownership for an animated GIF that I had made. The system involves taking a certain kind of metadata, putting that information on the blockchain, and then transferring it from my control to his control. This was the initial conception and it got a lot of interest and attention. The people in attendance that were part of the Bitcoin scene felt that it was doing something significant.

Ryoichi Kurokawa, still from syn_mod.1 (featured on Sedition)

So, a mini avalanche of attention started, and we were invited to TechCrunch Disrupt where we pitched it to incredulous TechCrunch people. Since then it has been morphing into a functional platform. We have chosen to work in a startup format, which is the contemporary form de jour. And I don’t mean that in a cynical way, it’s a way to structure and develop an idea, to bring stakeholders into the project.

We hope to have something up that people can sign up with and start using soon. Right now there’s a lot of interesting software at the API level, which just isn’t attached to anything yet.

Working with a small team of people, the process of turning it into a platform has gotten bigger in many regards, in terms of the kinds of possibilities we want to enable. We’re working on trying to figure out the larger ecosystem and the range of things that can happen if individual creative people are registering their media works as soon as they hit the Internet. If we have these tokens that represent ownership of those artworks, we’re asking “what kinds of things we can do with that?”

I want to see what kinds of possibilities the system will enable. The project responds to the frustration of the current status quo of handing over creative works to online platforms that monetize the value through advertising, which is 99.9% of the internet. It seems like there have got to be other alternatives.

Saul: But how does Monegraph not monetize it?

Kevin: Well, it monetizes it for the creators.

Saul: If it monetizes it for the creators, it monetizes it for the consumer. There’s obviously a secondary platform where there’s another level of exchange. i.e. I now own, or this has been transferred to me, and I can now monetize my ownership of that transfer.

Kevin: But you can also give it away.

Saul: One can do that with any work of art.

Kevin: Right, but in digital form, you’re always dealing with a third party and the third party’s ability to maintain –

Saul: I can give it to a museum, I can give it to my friend, I can give it anyone I want. The value transfers with the object. How is this not just another object?

Kevin: You can make it a kind of object.

Saul: How does this not just replicate the object in an immaterial manner? It’s exactly the same system that we already have. For example, Sweden will be the first cashless economy. There’s literally no paper currency exchange going on. It basically lives on direct deposit. How is this not just a credit system?

Kevin: It’s not. These aren’t monetary units.

Saul: Well, the dollar bill wasn’t a monetary unit until it was introduced as a monetary unit. Paper money wasn’t a monetary unit, it was introduced and, by convention it became a monetary unit. How does this prevent that?

Kevin: It doesn’t prevent anything. People will exchange value however they want to exchange value

Saul: So it’s capital’s wet dream.

Kevin: I could take the offline printed magazines and trade those. How is that not capitalism’s wet dream?

Saul: Because there the exchange is actually for a material object that has limited access and what capital would love at this point is to profit from something that is immaterial.

Kevin: So things that are immaterial can’t participate in any type of virtuous value exchange?

Saul: The question is: do we want that which is immaterial, which seemingly would escape commodification, to be turned into a commodity (except for the fact that artists need to make a living)?

Kevin: So, in your view, the current online world is a utopia of non-alienated usage because there is no use value to these digital things, so everything online is by definition escaping capitalism?

Saul: Right. And that’s the reason capitalists are constantly trying to figure out systems by which to produce exchange value for everything that’s online.

Kevin: They’re doing a pretty good job if you look at the stock prices of Google and Facebook!

Mike: Many of the champions of blockchain technologies in the non-art world have vaguely libertarian aspirations, or at least they dream of creating something that can exist outside of institutions like the Federal Reserve. What I find so interesting about Monegraph is that it seems to empower just the opposite. Perhaps it is actually something that Sotheby’s or Christie’s might want to use to authenticate a work. In the piece on Medium, Anil Dash talked about how the problem always lay in authentication, a central component of trading art. So is there an inversion here. You could make the argument that Monegraph, in taking blockchain and applying it to digital art, actually empowers institutions the traditional market.

Kevin: Well, some of this goes back to when I was into the New York net art scene in the 90s at thing.net. There was a project that was based out of there by an artist named Paul Garrin, who was the long time studio manager of Nam June Paik’s studio. The project was called name.space and it was an alternative DNS system. He identified DNS (the Domain Name System) as this choke point of control and censorship in the Internet and was advocating for a decentralized version of domain names.

Jennifer and Kevin McCoy, Shore Leave, 2014

The other idea in the back of my mind, going back to the Bitcoin community, is Alex Galloway’s book Protocol: How Control Exists after Decentralization. He sees protocol as a site of political contestation. For me it was interesting that Bitcoin emerged in 2009/2010. It matured, and then in 2011 it reached its ideological golden age where the currency didn’t really have much monetary value; people were just thinking about it in obscure forums. One of the first spin-offs of it was Namecoin—the blockchain that we ultimately used. It was about alternative DNS, making these pairings with a name, using “.bit” or whatever; or IP addresses, and storing those in the blockchain. All the while I’m thinking that’s what Paul Garrin was trying to do ten years ago.

I think that the gesture of autonomous control of naming in a public space is an important power. We can call that authentication or we can call that provenance, but the original thing is an author claiming something, drawing a line around something and saying ¨this thing, right here: I made that.¨

It’s been very difficult to do that in a networked digital world. Once that name is there, and especially if it’s transferrable, somebody could sell it off. And somebody could use that name to track—it’s coming back to the idea of an artist’s signature. The artist signs the work and suddenly that signature becomes valuable later on, and a market is created around it. You don’t have to use this approach. You can have unsigned or anonymous work, but the idea of empowering an artist to claim an artwork and have it be tradeable is useful.

Morgan: Can you talk a little bit about Monegraph the platform?

Kevin: The site as we presented it to the New Museum, where we walk through the steps of producing the metadata record, is still online at classic.monegraph.com. That site never did have any way to integrate with actual blockchains and to handle the virtual tokens that it takes to write data to the blockchain. It never dealt with the management of the public keys that represent the ownership of those values. In the Bitcoin world, that’s all called ‘wallet software’. Trying to add that kind of feature into a platform, that’s at the core of making it easy for people to use, getting that data onto the blockchain, making it easy for people to manage private keys, which represent the ownership of those tokens, it’s all very difficult work.

We’re also trying to develop contracts for different possible use cases. If you think about artworks and the kind of exchange, the equivalent of a painting or an object. I made an object, it’s mine, I give it to you, I don’t have it anymore. Now you do. That kind of oneway hand-off is just one kind of use case. We’re trying to think about other possible use cases that represent activities of the broader Internet that aren’t just about fine art. It could be about commercial art, licensing, or whatever.

Morgan: Zoë, the EO1 is partly a device for displaying art, but it’s also an art market. Can you talk a little bit about how that market is structured, and the design of it? Is it trying to solve some of the same problems as Kevin spoke about above? It seems perhaps that EO embodies the same strategy of imbuing digital art with some of the characteristics of physical art objects.

Zoë: Electric Objects is trying to solve this problem of how you, in the words of one of our beta testers, Alexis Madrigal, give objecthood to digital art. First, we’ve created this frame that art that’s made for screens can live within, but the second part is the marketplace, and that’s where our community of artists and art fans, or collectors, come together and support one another. Right now, we have about 30 artists that we’re working with who have agreed to experiment with the device.

We’re going to promote a collection of works made by some of these artists. It will live in two places, both offline and online. Offline, it will be at the Ace Hotel for a month, on display in real life, because Electric Objects is an experiential product. You have to see it to understand it. Showing the device with the art living inside of it really sells the whole experience. One can’t exist without the other.

Nicolas Sassoon, Grey #2

Morgan: How do you handle licensing, pricing?

Zoë: We have a more “Internet” approach to pricing than a fine art one. We’re looking to iTunes and the App Store, for example, for inspiration on how to build this marketplace. We want to create a simple buying process, with one consistent price across all works so that a buyer doesn’t have to question why one animated gif is worth 10 dollars and another is worth 50 dollars. We have a big challenge ahead of us, which is convincing people to buy digital art and digital art files. Not a lot of people have experienced the value in that, so we want to make the process as simple as possible.

We’re also exploring the possibility of a subscription model. You can subscribe to an artist or curator who would effectively curate your EO1 for you. We’ve heard a lot of feedback from people who say ¨I don’t know a lot about art, but I love this technology. I trust you guys to tell me what would look cool on my screen. I would pay you a monthly fee to do that for me.¨ It’s almost like Songza. It’s a curated channel of art rather than music, which is what Songza does.

Mike: I actually didn’t know that you’re doing a flat price which is an interesting way to structure the exchange of art. It makes me think of CDs—a Beyoncé CD used to cost the same amount as an indie band that just happened to be Tower records. That is obviously flipping the art world on its head, because we all like Gerhard Richter, but none of us can afford it. If you want to induce a wide array of consumption of art, flat pricing is a bold strategy for achieving that.

Some of the early utopian discourse around net art emphasized the immateriality of it as a way to circumvent the art system. Here it’s basically finding a middle ground and saying, there’s some exchange value, but we’re going to make it accessible in a way that prevents the “star system” model of pricing. For me this also calls into question how art capitalizes on authenticity.

Saul: Except flat pricing here is, for access, not for ownership.

Zoë: It is for ownership. It is in perpetuity.

Saul: But there’s not one.

Zoë: Right. There’s not one.

Saul: Or, in terms of Monegraph, it’s not exchangeable.

Zoë: Right, so there’s not anything in place that could support a secondary market.

Steven: Sedition does that.

Zoë: Indeed, you can buy a work on Sedition and store it in your account afterwards on their platform. I’ve never personally – have you ever done an exchange?

Steven: I’ve purchased, I haven’t sold.

Morgan: Do you want to explain what Sedition is?

Kevin: Sedition is based in London and it’s the first effort to create a digital art marketplace. They’ve been running for 5 years, and they essentially have art world names at really inexpensive prices.

Casey Reas, still from 100% Gray Coverage, 2013 (featured on Sedition)

Steven: I thought Sedition went the wrong direction in the early stages. To me, they were exploiting well-known contemporary artists, presenting their screen-based works as new media experiences. It was related to what Bill Gates did many years back, he thought he was being progressive at the time when he was taking the digital rights to say, Mona Lisa, and putting the image on a screen. It was interesting to a degree, but it wasn’t interesting as new art. It was interesting as a potential platform. Sedition is actually mixing it up now, they are moving toward artists who have a foundation in the new media world.

I also think the whole concept of Sedition being a collectable model of trading is misguided. Once they decided to go with low price, super high edition, they broke the whole system. It’s not about value anymore, it’s about exposure. And that’s a good thing.

It’s about, and what you’re doing (Zoë), is about how these artists gain exposure. Then, the flip side potentially can happen when the Sedition artist’s works are presented in an art gallery and all of a sudden and there is an offering of unique works or small editions where there could be a potential market made, which then comes down to how you authenticate it, and that’s where Monegraph can play a major role.

Saul: It’s very much like Hundertmark in the 70’s. Basically, they produced editions for 100 marks, unlimited, and you could own something by a name artist. At a certain point, they’d stop producing, the demand was no longer there, and all of a sudden the thing would accrue value.

Zoë: So that’s always the case with a secondary market, right? When you act as a collector, the dream is … for example, my father is a collector of robots. His house is full of them. I know that some of them are really precious and are worth money, and those are the ones he won’t let me touch. Then there are many other robots that are never going to be worth anything. But your dream is that you’ll come across a five dollar robot, but then 20 years later, it’s a 500 dollar robot. I think that’s what drives a collector.

Steven: These models aren’t for collectors, it’s for experiencing interesting art.

Saul: But that’s the vein that produced the collectible market: pet rocks, Garbage Pail Kids stickers, Beanie Babies …

Steven: The difference here is this unlimited potential of distribution. That changes everything. For the pet rock, the guy goes out of business. It’s a little harder to stop that software distribution.

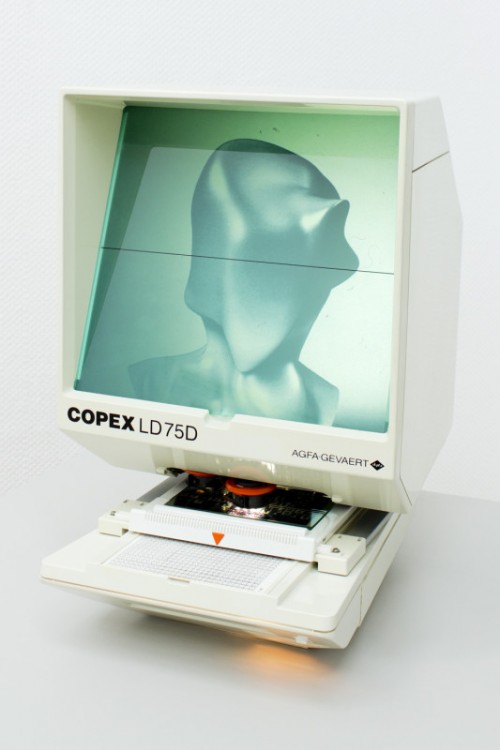

Jon Rafman, New Age Demanded Microfiche Archive, 2013

Saul: As this is being built on a certain platform, what happens as technology changes?

Steven: Cloud based distribution responds to that a little better in terms of how things will evolve.

Kevin: You could say, I mean, this was an old fashioned idea from 90’s net art, that there was a medium specificity and that you couldn’t translate from one mode to another without loss or without an unwanted context shift. You (Mike) were saying about this utopian moment of net art, where it was perceived to have no value. I definitely would have an early generation and later generation divide, but for me, I wouldn’t put it around a question of perceived value. In my experience, with this first wave and where you cut it off, people were concerned about looking closely at these platform and protocol questions and critiquing them trying to come up with alternative systems or critical engagements. And then there was a shift to just using platforms: Tumblr, Twitter, Facebook, blogging software, whatever.

Saul: Right, the artist becomes a content provider.

Kevin: Absolutely. To a certain extent, that feeds into Monegraph. I’m part of that earlier generation and always kind of incredulous of the ease of use of these mass platforms. Especially in the face of them having massive valuations and the content providers having nothing. They’re stripped of all value, even though it’s clear that there’s a lot of direct value in those works. Obviously, there’s people who figure out how to use that in an expressive way, and drive their projects and their careers, and the kinds of economies that do happen in these platforms. But it is very different…

Zoë: Nothing is free. If you’re an artist and you’re publishing your art on Tumblr, for example, be weary that the stuff you’re making is viewed as content to them and that they use that content for marketing and advertising purposes. When you use their services, you agree that they can do just that.

One of the first rules we made at Electric Objects was banning the word ‘content’. I don’t believe that I’m working with artists who create “content” for Electric Objects and I would never approach an artist to do that.

Saul: What are they producing?

Zoë: They’re producing artwork.

Saul: Yeah, but what is artwork in this context of a content? I’m an author, I write a catalog essay, I’m supplying content. It doesn’t matter how you qualify it.

Steven: Well, c’mon…

Saul: It doesn’t matter how you qualify it—

Mike: Right, but even though you’re providing “content” for a book, it’s the combination of the content and the form that constitutes writing, which in this case has its own history.

Saul: The only difference between me and somebody else, another type of author, is that I get two dollars a word and the other author gets royalties.

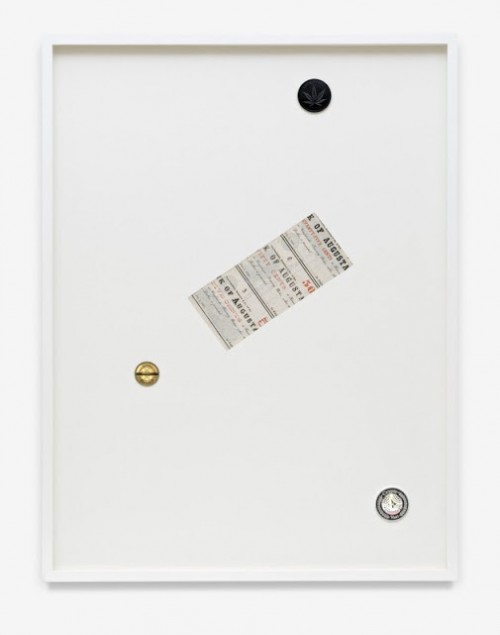

Seth Price, Redistribution, 2007

Mike: A certain genre of art has been dealing with simply putting food on the table for a really long time. You have 60s conceptual artists dealing with immaterial practices, and then there’s Seth Siegelaub and Bob Projanky’s “The Artist Reserved Rights Transfer and Sale Agreement,” which sought to include artists on subsequent increases in the value of their work, among other things. Then there’s also performance artists …

Kevin: We used that contract in our investor decks!

Mike: Ah, well, likewise in the past there have been artists whose practice make it extremely hard for them to make a living. I think everyone at this table wants artists to be able to have a sustainable practice. It’s interesting that there are a lot of different approaches to it. I see maybe three approaches at this table.

1. One being, if your piece goes viral on Tumblr, one of the four million people that sees that piece, now they can (potentially) verify the digital signature then look it up later to find out who that person is, and find the original image. As such, you can support the artist who makes that.

2. On the other hand, you have a flat subscription model via a platform like EO that artists may be drawn to.

3. And then you have Bitforms, where you meet halfway and take art that has new media forms, but presented in a traditional gallery format.

So it’s really about what artists face with these new platforms. What are the concerns that they have when they are creating pieces that are digitally native? Obviously Monegraph is a new case: for example when you put something on Tumblr, and it’s not only just out there. There may be a place to trace it back, to not just be a content provider.

Kevin: Even though Tumblr in their licensing says you own the work and we have a license to it, effectively it’s gone.

Mike: But if one were to pull down the image from a Tumblr and use it again. For example, if I saw an interesting image from tumblr that has been reblogged 4,000 times and I downloaded it and then I put it on my website. Will it have uniquely identifying information?

Kevin: There’s a lot of details … Monegraph is not some magical anti-piracy technology that stops usage illicit usage of media. It creates some opt-in ecosystem that works as an incentive

Saul: Given the recent conversations in terms of guaranteeing artist rights in terms of resale, royalties, so on and so forth, is it much more of a platform for that?

Kevin: It can be.

Saul: Does it become like ASCAP?

Kevin: I think so … and this gets into the smart contractual language as programmatic code.

Steven: What happened to Creative Commons?

Kevin: We see Creative Commons as a big, early effort, and we see ourselves as trying to move further. It deals with an attribution issue, which is great, and it also has noncommercial uses that have real limitations. So, for us, Monegraph, with its transactional nature, allows for commercial possibilities.

Saul: Creative Commons didn’t allow for any way to track intellectual property. It had a good will policy. Monegraph seems like it could be a way to track.

Kevin: Well, we’ll see. [As originally conceived, tracking is voluntary, but it could be built as a feature.]

Mike: I wanted to say that monetization isn’t necessarily a dirty word, because it also is a way for artists to actually make a living.

Saul: The question is, on the part of the artist or on the part of the collector, or the consumer, if it establishes a royalty agreement in which every time the artwork exchanges hands, the artist gets a percentage of that exchange value, that’s in service to the artist. If it was merely a system that authenticates that this is the product of that artist, and therefore, any exchange of it goes to the collector or the current owner, it would be less interesting because it’s a replication of the existing market. Right now, there’s no way to track those exchanges (of art objects.)

Kevin: I’m well aware of that distinction that you’re talking about and more progressive possibilities and more status quo possibilities. I don’t want to over promise, but our goal is to facilitate that type of transaction. There’s tons of digital media being sold online, and there are all kinds of existing marketplaces. There are systems in place and those systems have winners and losers. We’re coming from an artist-centric perspective as a kind of syndicate model and we think that we can change those dynamics in a bunch of different ways.

Eric Hu, 2014

Morgan: Zoë, I’m curious, when you’re designing a market for art, how do you think about how that might help artists build a sustainable business? I also mention this because Steven is obviously operating on a very different model and he expressed that there’s something crucial about the structures of value in the current art market, where art objects are scarce and they accrue value over time.

Zoë: One way to look at it is as an experiential model, like a show. We like to describe a lot of these collections of work that we’re putting together with artists as shows. It’s time based, it lives in this device in your home. Some of the artists we’re working with are creating projects that are durational. They take a month to execute from beginning to end, or they go on forever, etc.

In terms of generating a stable income for artists, it’s really about getting the numbers right. Right now we have about 30 artists and we’re about to have over 100 users. So if 100 users spend ten dollars each, spread across 30 artists, that’s not going to look like a lot. We realized that pretty early on. Our strategy is about growing at the right speed. I’ve been trying to do a careful job with how quickly we introduce work for sale. I should also say that none of this has happened yet, so I don’t have data for how much money people are going to take home. We’re starting with a grouping of three artists within this 100 person system and grow steadily from there. From this test, I’ll have data on how much money is going to come in and how that money gets distributed across these three artists. We’re going to learn a lot in the coming months.

It’s really a numbers game, and learning more about this audience too I don’t personally know all these people. They found us on Kickstarter. Who is this person exactly? What art do they like? I’ll learn as we go, and I’m hoping there’s a slow education for them too. This is maybe my personal curatorial mission, to promote artists that have this foundation in art and technology and share them with people who are really invested in hardware and technology. That’s the type of person who backs projects like us on Kickstarter. So, bridging these two worlds together through this device by creating that right balance in the ecosystem is the goal.

Morgan: Steven, I imagine you sell digital artworks in editions – what do you think about the possibility for digital artworks [files] to operate within the traditional gallery system while also being released into the wild online?

Steven: The Electric Object model and other models like that are only going to work if millions of people have a cultural shift saying, “I’m putting a screen in my house devoted to art.” Once that happens, everything related to screen-based arts will change. My business will change, your business will change. So there’s hundred’s of thousands or millions of homes with these devoted screen-art experiences. Just like when you’re hanging physical art objects on your wall, when you buy or are decorating a home, the question will be where can I place my “art screen”. It’s not a system that has TV content such as sports, reality shows or movies, etc. We’re not that far from this being a reality. Many of my existing collectors have already embraced this idea.

My collector base is also tiny compared to the rest of the world. Also my collectors, who are spending $10,000 to $50,000 on screen works, are an even smaller audience right now. These small numbers aren’t going to create the cultural shift which is needed to sustain a more substantial market for this kind of artwork. Again, I have different opinions on this whole $10- $20 for each artwork versus what I’m doing. I think they can co-exist because I do believe that these very large editions become public art forms based on how the web distributes images and content. Very different from the commercial art gallery model based on scarcity, like I deal with. There is a different monetary model.

Just like in music, there will be your art stars that may sell a million things for $25, and that’s a lot of money. It will be just like a pop star, in any industry you’re going to get your stars who are going to blow up, but in terms of my world, I’m still dealing with scarcity. I’m still dealing with an audience that can spend $30,000 to $40,000 dollars or more on a screen-based artwork, whether it’s unique or an edition of six. At this point, there is an odd trust involved with my collectors with art that is obviously reproducible very easily. The success of video art and photography have had a big impact on me supporting this concept because those are all reproducible and have a proven track record of success in the art world.

Ryoji Ikeda, A Single Number That Has 124,761,600 Digits (featured on Sedition)

Morgan: You said “odd trust.”

Steven: It’s a trust because it’s a lot of money in some cases and it is …

Morgan: We’re talking about selling a digital file, but …

Steven: If it was a software-based piece or a QuickTime movie yeah it’s fine so there’s … it’s grown quite a bit since I started the gallery, this trust, and the market. It’s still small but it’s growing and I think that if there is a more credible way to track, to authenticate [i.e. with Monegraph], it will make my job a lot easier in terms of distributing this kind of work, especially when you hit the high numbers. I think the auction market is all about that trust and credibility and it’s …

Zoë: I’m sorry. Those are the questions that I wind up having when I think about a system like Monegraph, is that I need to trust this decentralized group of people not to authenticate something as their own and lie about it, whereas institutions like Christie’s or Sotheby’s have a track record of selling mostly authenticated art, right? We all know there have been some forgeries that have gone through, some auctions here and there, but for the most part they come to the table saying, “look, we have these art historians. They looked at this thing. They put their certificate of authenticity on it,” and you’re trusting the auction house.

With the absence of that what happens when those files start … I guess it’s less scary when it’s coming directly from the artist, but when it’s going through a number of hands like if I’m getting this from someone who bought it from someone else who bought it from the artist, that’s when I would still … I don’t know. I think I would still worry.

Kevin: Sure. The Bitcoin community loves this phrase, in Latin it’s ‘truth in numbers.‘ For them, it’s the math. It’s mathematically sound. Within the functioning of the protocol, that’s all good, and the creation of these virtual tokens, the exchange of these virtual tokens, all that makes perfect sense. But, as soon as you deal with, “I wanted to sell my bitcoins for dollars or for euros,” once you exit the system and those edge conditions, then all of a sudden it’s another story.

Zoë: Right.

Kevin: Using the blockchain as some sort of ledger of assets is going to be all about how does that data hit the blockchain? What’s the way that it hits? In the case of Monegraph, with us as a registrar, then we need to be transparent and provide mechanisms of verification to allow you to double-check what we say is true.

That’s part of our protocol definition that will say, “here is how we identify the artists,” and you can double-check all those steps. “Here’s how we verify the artwork.” This is the data that’s on the blockchain. You can re-verify that with the data on the blockchain and the artwork, and if it matches, it’s all good. If it doesn’t match then …

Zoë: Then you know it’s false.

Kevin: Right. Then you know it’s false.

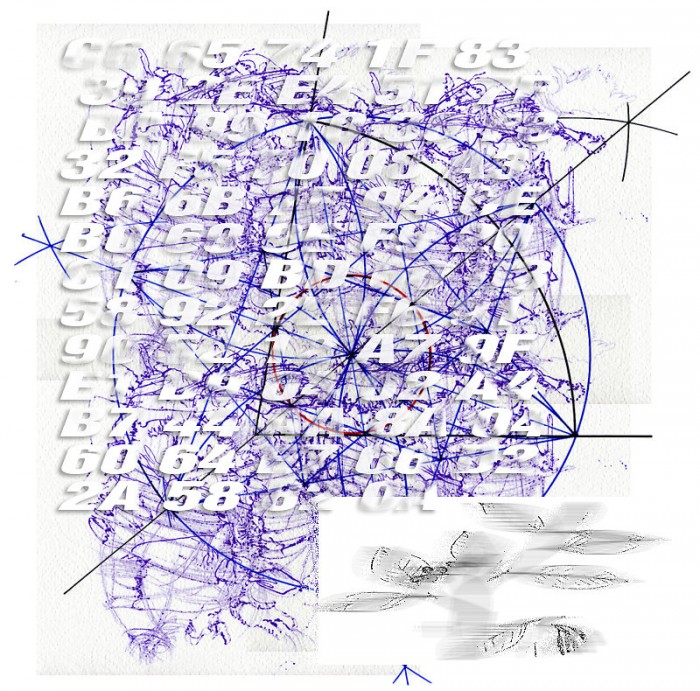

Lars Holdus, 6 D2 2A 58 82 0A

Morgan: Adriana, I was just curious about how you think about your own work in relation to these systems?

Adriana: It’s always interesting being in a room with people thinking about how to sell work when you’re this person that’s thinking to yourself “how do I sell work? Where do I fit in with all of these different existing or speculative scenarios?”

With Monegraph, I am imagining it would have implications on art objects in general regardless of digitality by providing an additional layer of verification and tracking.

Authentication and provenance, as we have discussed, are certainly important. Why is it not enough, for example, for one to simply claim that they are the creator or owner of an artwork, with the secondary verification or the artist or gallery or whomever, and allow it to reproduce as much as it wants, in accordance with the digital medium? It’s clear that this is still far from as lucrative as the market for physical works, but puzzling given how abstractly and symbolically physical works are treated (like stowed away to accrue value). And, if a public ledger of verification is to develop as in Monegraph, would physical works also have to be a part? What would happen to relatively old fashioned titles of ownership?

Coming to mind is one of the most recent pieces (of many!) I’ve seen thinking about the financial circulation of an artwork, Real Flow’s Art is the Sublime Asset™. It presents ‘tailor-made financial solutions’ for ownership and investment in artwork in which the owner benefits from the increased circulation of the piece by the investors.

I also feel wary of a subscription-based or very low flat pricing model that was described in relation to EO. Does the EO have exclusive rights? How is the money split? Or generally how would it work from an artist’s perspective? What incentive would an artist have?

Zoë: Our licensing agreement is that you retain the full license to the work but you’re giving us an exclusive license to sell and distribute the work via the EO1. The revenue split from either the subscription or the per-piece sale of the work is 70/30, 70 percent to the artist and 30 percent to Electric Objects. We believe that when artists are making money we’ll make money, so we want to make sure that the system that we create is always benefitting the artists. Because we’re selling this hardware device on top of the art sale, our job is to create the audience for the artist.

The opportunity here is access to the audience, the context of being in people’s homes, tof working in a durational practice or even working with the Internet, since it’s an Internet-connect device. It’s connected over WiFi 24/7 – what could you do with a website? We’re hoping the hardware and the platform creates an interesting artistic opportunity and that the licensing model is fair, and that will attract artists to the platform.

Real Flow, Art is the Sublime Asset™, 2015

Morgan: I’d like to quote something from Jennifer Chan’s From Browser to Gallery (and Back):

“Inquiring into the concept of aura in relation to traditional and digital forms, Gene McHugh noted that Benjamin had never provided a concrete definition. However, he proposes that—

Kevin: —But, he did provide a concise definition of aura! It’s the material traces of the object through time and space.

He gets a definition of the aura that’s a material history of the object through time and space. The marks and—

Saul: —As it traces on the surface of the work.

Kevin: Exactly. It’s a totally materialist conception of the artwork …

Saul: That is only available when you’re in front of it.

Kevin: It’s very clear.

Saul: Aura is patina.

Kevin: He uses a loaded, spiritual term to describe what’s entirely a material record.

Morgan: (continuing) … he proposes that the “ornamental halo” Benjamin described of viewing an original artwork stemmed not from an artworks ahistorical, timeless beauty, but from an underlying notion of a linear social history to an artwork. This includes ideas of where it has been exhibited and who has owned, bought, sold, and handled it. Regardless of size and quality, the existence of art documentation on the internet testifies to an original idea of an artwork having been installed somewhere in physical space, thus lending the art objects authority and validity in distribution.”

I’ll read one more quote:

“Net artists often gauge community responses to web-based art through the liking and sharing of a project’s URL within and beyond an online community. In a networked environment, attention and peer approval is currency for freely accessible media. In reconsideration of the Benjaminian aura of net art, McHugh observed that artwork gained authority not only through its provenance, reproduction and social transactions, but its dispersion through smaller niche communities.”

I thought it was interesting in relation to what Monegraph models. Monegraph is modeled on provenance, which in a way is an attempt to import Benjamin’s notion of aura into the digital world, or make that a concrete reality for digital objects, whereas this is suggesting that actually the mechanism by which digital art objects accrue value is fundamentally different.

Kevin: Two key words that she uses: currency and dispersion. Regarding currency, there’s absolutely no question that within major social media platforms, you’re dealing with a currency of attention that’s manifested through likes and shares and re-blogs and that kind of thing. That’s the currency that you are given as a creator. In the platform it’s getting a different kind of currency from that. You’re getting dollar currency through the ad sales and through their stock prices, so there is a currency arbitrage that’s happening there. It’s an attention-based economy versus … it’s supported by a dollar-based economy on the level of the operational platform.

Monegraph which is … before it’s a system of provenance, it’s a system of virtual currency because it is built on top of a distributed virtual currency directly. It is an attempt to create an alternative, that an artist could choose to opt into, that would allow for them to explore different economic participation than the attention economy. I don’t know whether it replaces it. It might just be superimposed on top of it, and it could eventually be that the Monegraph economy is openly more viable to them than the attention economy, so it’s really just about proposing, or establishing the possibility for the creation of an alternative, I think.

Saul: Or there’s a collapse of the two.

Kevin: It could. That’s a very interesting question. You could say Monegraph as a platform is trying to be flexible enough to accommodate both of us.

Saul: Right.

Kevin: It could be like a straight-up sale model that’s like … even I have an offline monitor after that went offline in many ways, but it’s just an online verification of the data, that the data itself can stay offline so it doesn’t have to be online. It also can allow for the artist to directly participate in the attention economy in a quasi-advertising way.

Saul: It’s about circulation.

Kevin: Exactly. If you can track … if there’s ways in which you can essentially track that circulation, then there can be ways in which you can … all kinds of visual possibilities are there.

Sabrina Ratté, Littoral Zones, 2014

Mike: When you said these could exist offline my ears perked up. I start to think about the idea of the blockchain and the currency that is distributed (i.e. no one owns it) and yet when we think of the broadly Leftist critique of big data it revolves around the idea that once we’ve stored data we can’t escape issues of control of that information. What would that mean—that this data would exist offline? For example, you have this trove of information that has authenticated all of these digital artworks that have existed in the past x years, but then you take it off a network so no one can access it. In our case, would it be like Sotheby’s, Christie’s, or the network of academics, all of whom are an extremely closed group that essentially control the ability to bless something?

Kevin: There’s two things. There’s the identity of the artist and the artist wanting to prove their identity, and that’s a profile question. The artist has to create a believable profile that shows that the statements that they make, that they publish, are their true intent and not somebody else’s, so there’s a threshold of believability for that, a procedure you can go through. Then there’s the work itself. How do I know that this is the artist’s work and this work hasn’t changed in any way? The belief that the artist is who they say that they are probably is going to involve some online social component because that’s widely distributed data or whatever …

We all have social profiles. We could say, “Okay I’m going to just simplify that problem by piggybacking on top of social networks and creating a meta-identity across all these social networks, I am who that I say that I am.” A lot of people do it. Then there’s me so I have an authorized channel, so then if I say, “here is this artwork,” and I describe the artwork not in terms of a URL, but in terms of other kinds of metadata, data that’s intrinsic to that file itself, I don’t have to show that file right now. Then I say, “okay I’m going to sell this to you,” and you’re going to say, “okay, how do you want this file?” and I can show it to you on my phone or offline like, “here it is. Check this out. Here’s the files,” and you go, “okay, cool. How do I know that that’s really the file that I’m buying?”

We could run those checks on the file and compare the information. It’s like here is the information that is published. Here’s how we identify it. We’ll run these tests offline. It checks out. That’s the file. The data has never hit the Internet. The registration, the authorship of the provenance, is online, broadly distributed in the blockchain, but the data itself doesn’t have to be online. That’s an example of social practices that I’m really interested in seeing unfold when Monegraph is a platform, because people will use it in all kinds of different ways that I don’t really know about or can think about. Another thing that we can do is make a physical object that’s specially laminated, and inside of that object is the password to access this online blockchain address. It’s hidden and you have to crack it open, and once you crack it open and the security is blown, you know that it’s been accessed so the data is available online.

Brad Troemel, 1 Casascius Gold 1 Bitcoin Piece / 1 Confederate currency note / 1 Counterfeit AOCS Live Free or Die Coin, 2014

There’s a company that took, and this happened first in the Bitcoin world with Cassius Coins, where they take … it’s all called a paper wallet in the Bitcoin world and this is a paper wallet of it where you have the public address and you have the private key for that address together in the same place, and you just hide the private key so no one can see it, or it’s self-evident when it’s tampered with to reveal what that code is.

Morgan: Can we imagine a digital art world that works for artists distributing work online, and if we look at …

Steven: It’s going to be awesome.

Morgan: …It could be. I don’t know if this is really at stake here, but I think Adriana is part of the generation of artists that were online and largely in the last six, seven years or so transitioned over and over again from making online work to making physical works in order to participate in the standard art market and …

Adriana: Not to cut in, but I’m not sure the relationship is so perfectly linear. Though it’s undeniable, it’s not one I identify closely with myself. Just to say that just because someone that works digitally makes something physical, it doesn’t mean I have to participate in the market and now let’s all make something physical. Perhaps there is also that impulse as well.

Saul: Obviously there’s two different things here, one where the digital is merely a medium and one that produces anything using that medium, and those who are committed to the digital as a mode of output. Those are obviously two different things.

Kevin: How would you describe your decision to work physically or digitally?

Adriana: I think it would be like what he said — the former camp, that is. I work with what makes sense for the idea.

Saul: Within the notion of the medium there’s a preservation of the object of art. This thing where in the other situation, the output is limited to those forms of the medium. We know that there are people who make digital paintings and literally paintings are the output. That’s what is available, and then we know that there are other people who literally produce files. Those are literally two different objects or two … not even two different objects but two different things. We don’t even need to call them objects. They’re things. We have to ask of each of them, “what is it?”

Morgan: Yeah. I think what’s at stake here is things that are natively digital objects or things. Is Monegraph a system that can graft the system of value based on provenance onto completely digital objects, or things that …

Kevin: We’ll see if it’s the answer. To me it’s important to recognize that the question of the management of information in and of itself is not a new thing. We have copyrights written into the United States constitution and licensing agreements structuring human behavior around the sharing of information has been around forever: non-disclosure, etc. We’re surrounded by ways of managing flows of information.

I see Monegraph, rather than being some brand new concept, as just a way of using currently available techniques, and maybe a certain kind of insight about putting the technologies together, to shuffle up the status quo and rearrange the balances.

Morgan: What’s interesting though is that it makes visible provenance, which was previously invisible. It registers it in a public way. You could find an image on Tumblr and say, “Did someone buy this?”

Kevin: Before someone bought that in the Monegraph universe somebody had to make that, and you would know who made it. Then you would know its transactional history inside of the Monegraph universe.

Steven: Once again to go back, this only makes sense in an exchange economy because if somebody wants it basically they want it.

Kevin: Yes.

Kevin: It is so interesting how efforts to just map traditional practices in the art world – with institutions, collectors, Loans with secured application process, exchanges – how difficult that is to model digitally even at the most basic level. It’s very difficult. It’s very challenging.

Zoe: It’s never trivial, because we’ve been so used to this abstracted desktop world where we put files and folders in our hard drives we assume that we can equally map the real world into this, but it’s never that sample.

Saul: The nature of the digital, or networked medium is antithetical to these uses.

Morgan: I’m not sure if it’s strictly antithetical though. I started by saying that even the notion of a file is based … I mean, it’s called a file! That’s a physical object, so it’s actually entirely … the concept of the file was invented, it’s fictitious, so it’s not that it’s antithetical, but it’s not necessary. In some ways it seems strange to try to model the art world in a digital world because you don’t have to.

Mike: It reminds me of Lev Manovich’s work in general where he says that we’re always dealing with a series of numbers and all of the things we metaphorically graft onto it i.e. cut, paste, lighten, darken, trace … you’re not actually tracing anything. You’re simply accessing an algorithm in the software that model something that we used to do in lithographs.

Kevin: That’s a great component of it. The interface has this retrograde metaphor.

Mike: Yeah, part of his media theory is that we always had to use these metaphors or these terms when really all we’re doing is, in an ever-so minute way, is just altering the underlying information.

Saul: It’s the difference between the original PC and then Microsoft and Apple producing an interface that was graphical as opposed to command-driven.

Zoë: It made it usable to a wider audience. It was really difficult for someone who wasn’t computer literate to access this. I think that is the challenge we’re all facing here. It’s how we educate people on this mode of production, on this mode of artistic practice, and how do you buy, sell, and eventually trade this work? Yeah I think you’re right. We do have a choice. If we don’t have to model the art world then we’re left to go like, “Then what do we do?” and I think that’s how projects like Monegraph crop up and we’re like, “How do I apply technology to this problem that we have in the market to help people track provenance and sell their work?” Yeah you need to hold on to a vestige of something familiar for people to not scratch their heads and go, “I’m never going to use this.”

Mike: I think I just brought up my point because a mathematical solution is probably worthy of a mathematical problem, right? We can use all these different terms and we can use all these different transitions in and out of symbolic ideas about how we do these things. We can call it provenance, but at the end it does come down to treating a medium for what it is, which is zeros and ones to be simplified. I don’t know so it’s just …

Saul: Long strings of zeros and ones….

Simon Denny, Berlin Startup Case Mod: SoundCloud, 2014

Morgan: Steven, when people are buying a digital file they’re participating in a simulation of a previous kind of economic relationship. I feel like in a way it’s always fictional, that there’s a certain conceit that when you’re buying a physical artwork, you’re paying to have this thing whereas when you’re buying a digital object, it’s not actually, so to speak, that thing, so there’s a certain leap of the imagination. It’s sort of like, okay, this is the same thing as a painting, even though what you’re really buying is maybe rights to reproduce it or just a string of digits. I wonder what is going through a collector’s mind when they do this.

Steven: Well, first of all, the point when they are buying work like that is purely, again digital software, video based, I make it very clear they’re not buying something physical. And that’s the enjoyment of it, that’s the intrigue. That’s a main reason they’re doing it.

Morgan: What interests me about Monegraph though is the possibility to extend that logic further. So it seems to me probably it would be hard to do that sell if that original file was freely available on the internet? Do you ever sell a digital file which is actually publicly available?

Steven: No. That’s difficult. Although I do believe there’s value in this public art system, this net-based art being public and experienced, but in terms of selling that, I think it comes back to what’s currently happening, which is the domain name. Ownership of domain name and how that potentially could be monetized. I don’t know how, whether it’s a sponsorship situation or viewership fee, maybe they pay five cents to view this experience. But I believe that will become something. I mean, Rafael Rozendaal obviously sells rights to his URLs.

Kevin: And New Hive has sold a URL.

Steven: That’s right. NewHive is a totally different kind of model, which is also interesting. They commission artworks from artists on the platform and also organize exhibitions.

Saul: I don’t know your work [Adriana]. Do issues come up in terms of difference? Are they different?

Zoë: Yeah, versioning of work, like if you were to make – that’s a term that Lauren Cornell uses a lot – a software piece into a video, and then sell the video versus selling the software piece.

Adriana: They do. For example, in the case of one work, some things I am looking at are variances and vagaries in statistical machine translation and crowdsourced predictive text libraries. Each unique generated edition, specific to its moment, would create a chronology that shows these discrepancies and also changes over time.

Steven: Unique versus editioning for software has been interesting. I’ve really enjoyed that change over time, because a lot of the artists now are doing unique. I mean, the algorithm can change with one piece of code, and it’s unique.

Kevin: It’s a strategy I’ve used as well, too, like the series, you can do series, variations, that kind of thing.

Steven: Yeah, which goes back to painting and sculpture. But again, from a market perspective, the unique, the word unique has more value instantly.

Morgan: I think we’re getting at something crucial which is where does the value comes from in art objects and digital art objects? Steven for instance, when you sell a piece of digital art, it’s sold as if it’s a physical art object. Then maybe a piece of software, it sounds like there’s an added dimension there. So you’re not really selling an object but a system for creating many potential experiences. Which is hard to translate into other forms.

I wonder if Monegraph produces a new way of valuing digital objects that can perpetuate the aspect of the basic economic condition of the art market, which is I think unique in supporting individuals to create things with very little concern for their popularity or use value. The problem of digital art is that it affords economic systems that don’t have that property of supporting an artist in doing whatever they want to do. Maybe that’s the central issue that EO faces: can this do the same thing the art market does, or have the same property of being able to support people? I think the question I have for you [Steven] is whether you can use this idea of tracking provenance publicly to create an opportunity for a collector to support an artist.

Steven: Yeah, I’m a big supporter … I still don’t … I want to see it. I think this concept of the file and this feeling of retro recognizability, being comfortable, has to apply to what you’re doing. Absolutely. I know sometimes you want to go up against that, but in the art world, there’s enough traditional people out there who need to feel comfortable and confident. And they don’t want all this new lingo, and blockchain is going to freak them the fuck out, because they will not have any idea what that means.

Saul: Outside the that, there’s value at least in terms of artworks, there’s four or five different conditions of value. Some artworks take on value because their affect, i.e., they’re influential in terms of other things. There’s, so the notion of influence. There’s speculative value. There’s novelty value, we’ve all seen stuff.

Zoë: Pet rocks.

Saul: Pet rocks. And we’ve seen the art world version of pet rocks. There’s sustainable value, works fluctuate in price over time. And then there’s historical value.

Adriana Ramić, Unicode Power Stones, 2013

Mike: The art world’s “cloud” issue is that, I think a lot of these places misrecognize the fundamental thing that drives the market, and it is the very subjective and individual passion, it is the collector’s hunt, it is the collectors who like to feel some agency… not that it’s an illusion, but once you remove all of these accoutrements, once you optimize these things into this perfect smooth outline, it does sort of take away the raison d’etre of why this all exists.

So I think a lot of these places, like Artsy, who may have underestimated the extent to which someone doesn’t want the perfect NetFlixed recommendation. They actually want to think for themselves. They’ll consult a dealer, they’ll consult a gallery, they’ll read an article. But ultimately the way you get the ten thousand dollar premium on the piece is actually grows out of situation from which I don’t simply want to just get an alert notification— actually want to think about it. That’s why I was attracted to this particular discussion, because both of these platforms we’re discussing don’t totally remove that.

I just think that a lot of places, the first wave of these arts tech start-ups, chasing the sixty billion dollar industry are misrecognizing the space that they are trying to “disrupt.”

Steven: The “sixty billion dollar industry” that really can’t be grabbed in the way the start-ups are imagining …

Mike: Right, if you actually deploy really good software, if you actually deploy machine learning, if you actually deploy algorithmic matching of buyers and sellers, then it’s not a sixty billion dollar industry anymore.