Hank Willis Thomas | BRANDING USA

Keywords: 1968, Ads, Advertising, African American, America, Art, black, branding, Branding USA, civil rights, Commercialism, community, exploitation, gender, Hank Willis Thomas, Interview, Jack Shainman Gallery, NBA, NCAA, NFL, Prejudice, Racism, Reflections in Black by Corporate America, Sarah Lookofsky, Sexism, Unbranded, values

A conversation with Hank Willis Thomas and Sarah Lookofsky.

Sarah Lookofsky In Unbranded (2007), you remove logos and slogans from advertisements that feature black bodies, leaving them to “speak for themselves.” I found it striking that some of the images include very clear-cut racist and sexist stereotyping, while others appear more ambivalent, even defamiliarizing or unsettling when perceived out of their commercial context (this was especially the case for me with older images that are distant from the present moment). To your mind, does this series function to make apparent the racism and sexism that is otherwise obscured by the commodity allure or do you think that the de-branding might also in some cases free up the subjects represented from the overdetermining weight of the brand?

Hank Willis Thomas This is a great question. The project is actually titled Unbranded: Reflections in Black by Corporate America 1968-2008. With that series I took two ads for every year between the symbolic end of the Civil Rights movement, 1968 (the Year RFK and MLK were assassinated) and 2008 (the year our first clearly multi-ethnic president was elected). I wanted to track “blackness” in the mind of corporate America over these years and thought that by digitally removing all the text, we could simply look at them as images. As with most art, we bring our own preconceptions in decoding and reading them. I thought that my previous series, B®anded was too often interpreted to be about my own thoughts or feelings. With this series, the viewer is as much the expert as I am. If anything, I am kind of an editor. No one person can take full responsibility for an ad. They are reflections of a society’s hopes and dreams at a moment in time. What we see is what we get. So in a sense, I think your answers are in your question.

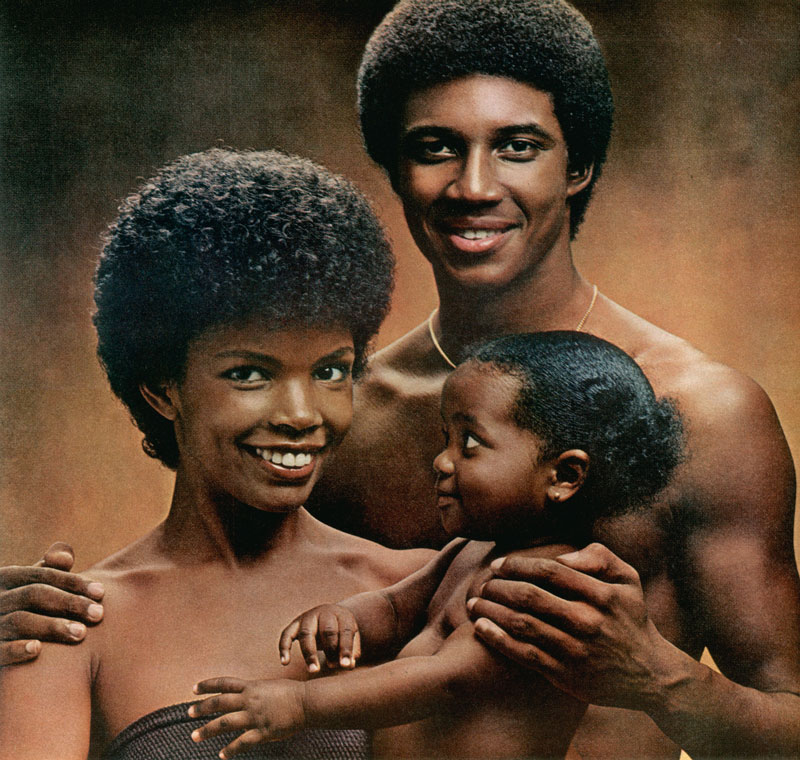

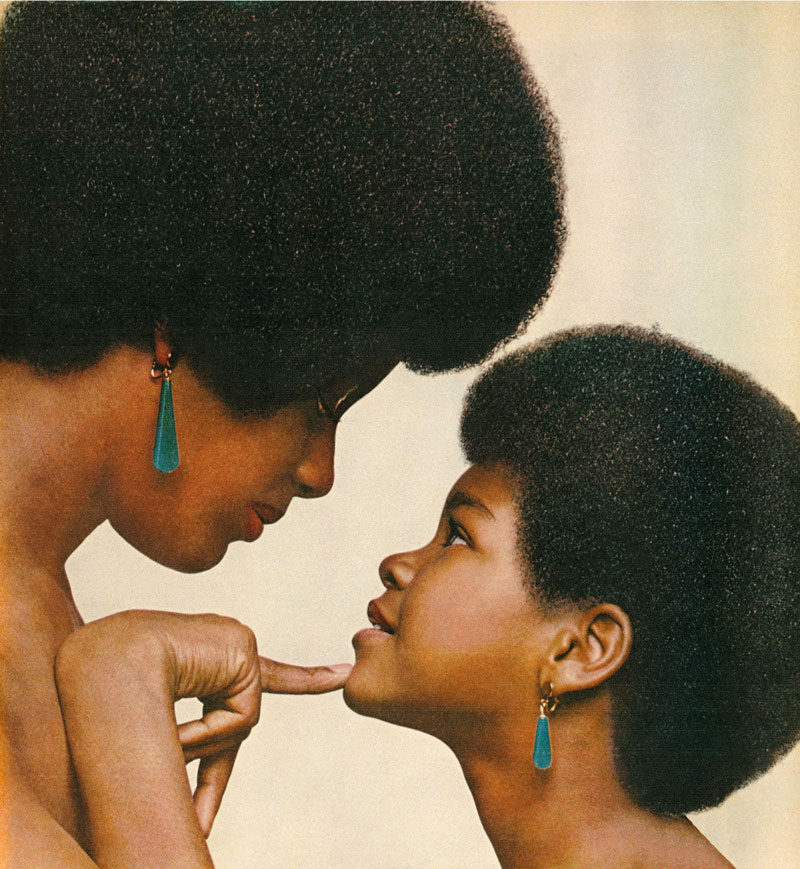

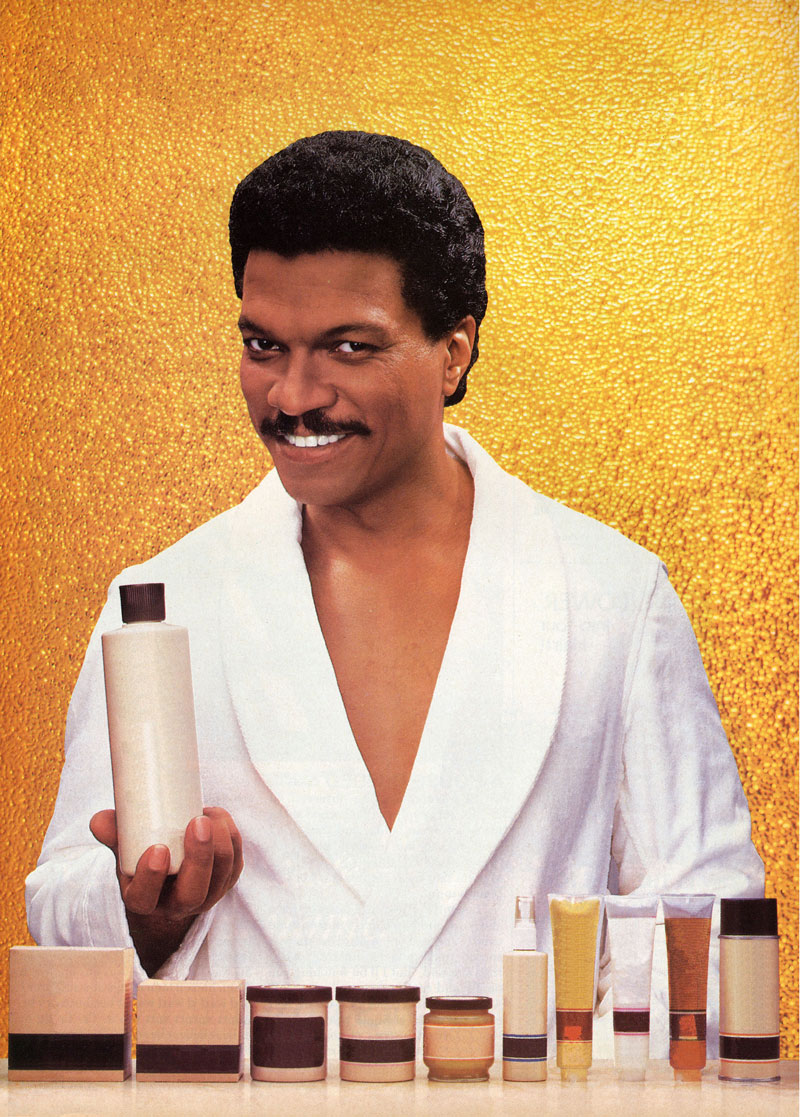

Hank Willis Thomas, Caramel Cocoa Butta’ Honey Lova- You’re Like No Otha’, series: Unbranded, Lambda Photograph, 1982/2006.

SL Viewing Unbranded in succession, with its advertisements from 1968 until 2008—and hence from a key moment in civil rights history to the year in which the first black president was elected—gives a clear view of how image culture has shifted over the decades. There are claims that we have now progressed to a “post-racial America,” but this image lineup seems to tell a different story: while positive developments in the politics of racial representations have no doubt taken place since 1968, Unbranded might also illustrate some counter-movements and regressive slides backward. How do you think about the changing representations that Unbranded gives testimony to?

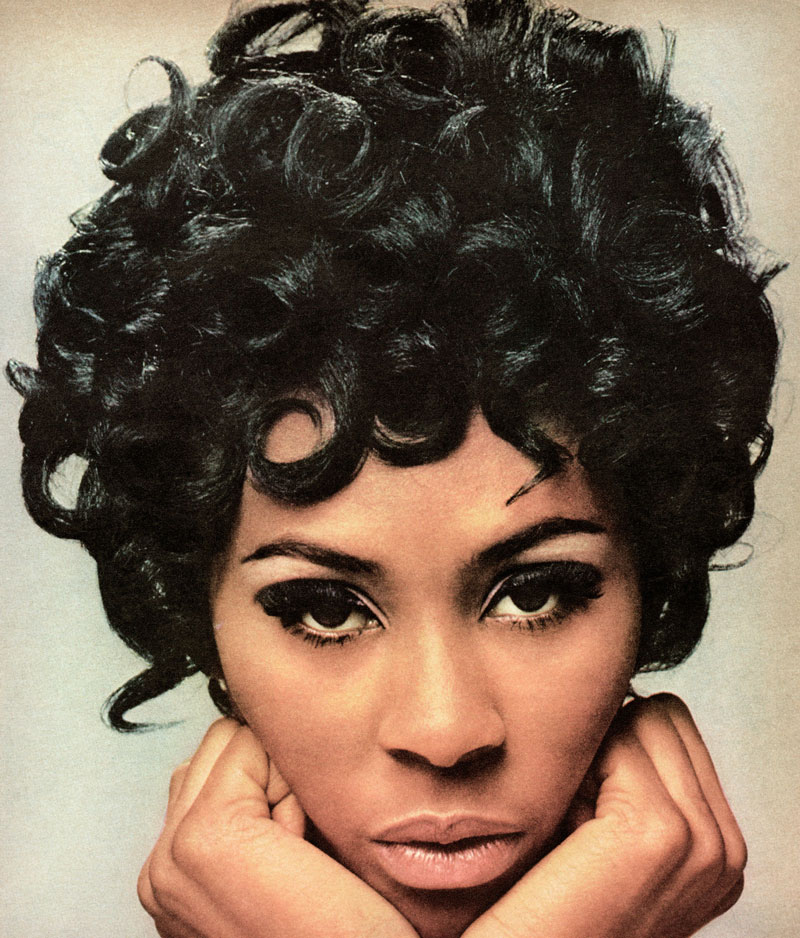

HWT I’m waiting for someone smarter or more informed to write about these ideas. I have a similar sense though. There are so many trends and strands that people could explore from issues related to class, family, hair, gender roles, values, the notion of a collective community, pride, and prejudice. All ads are based on generalizations, so they are inherently prejudiced. What does exposing these prejudices in this way tell us about ourselves and each other?

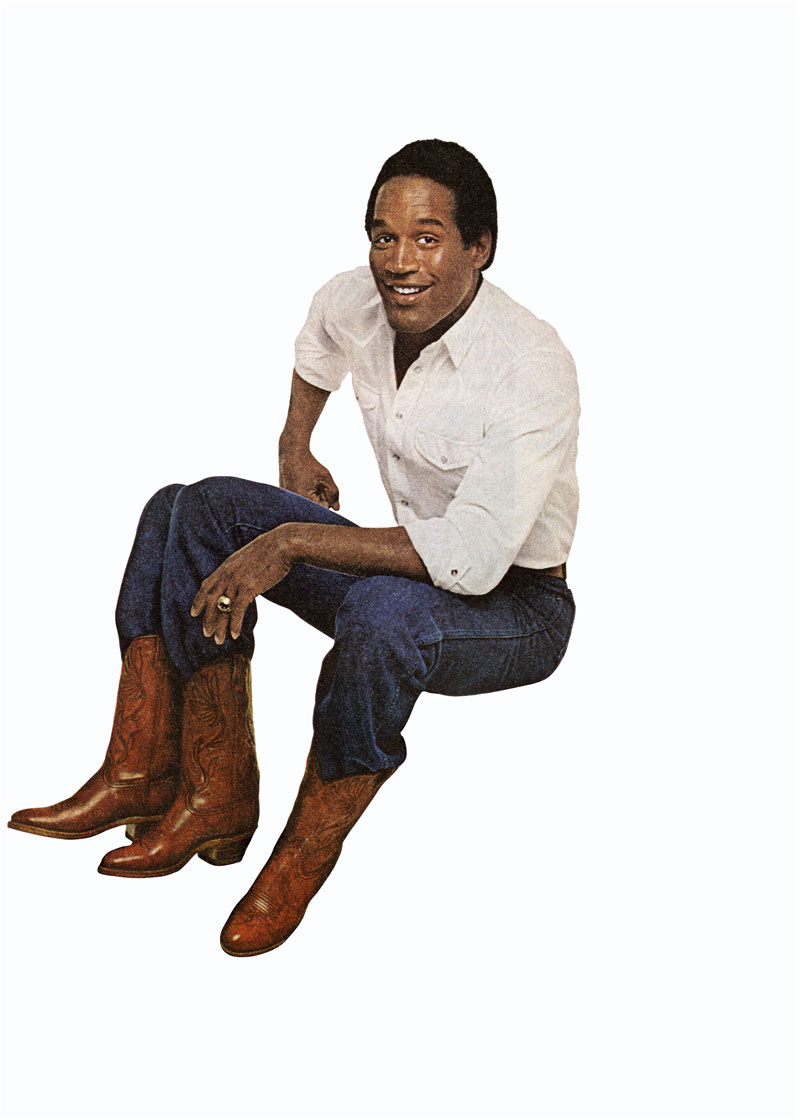

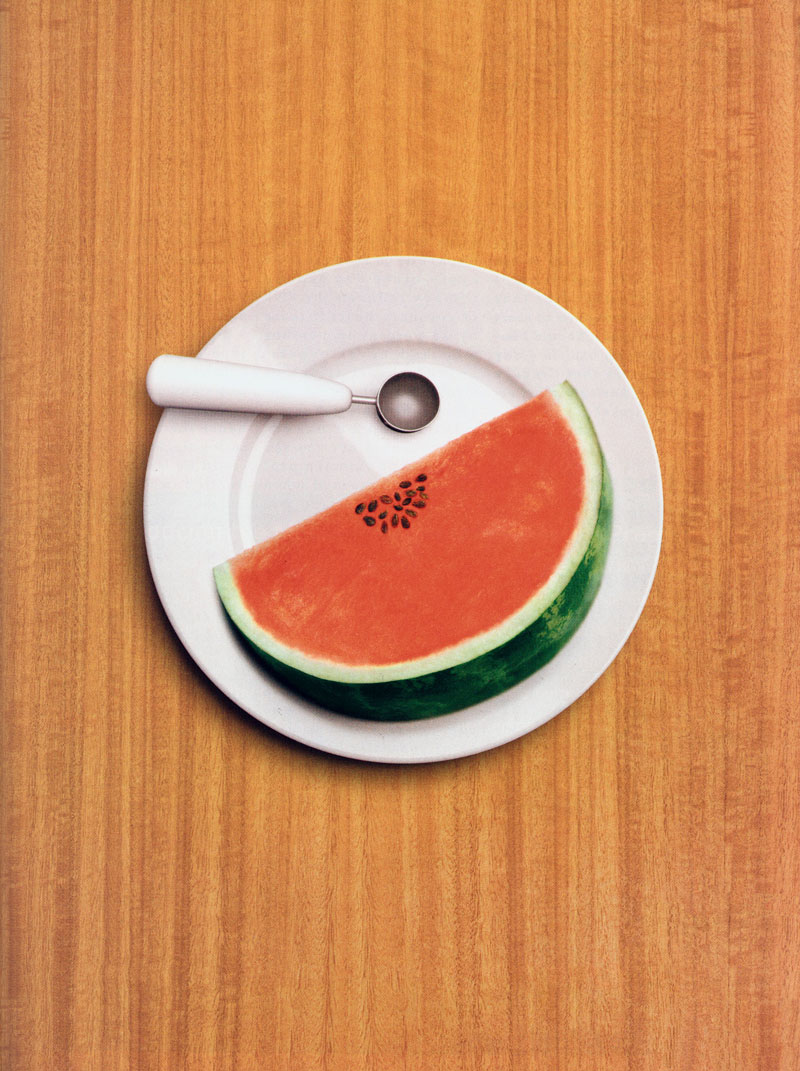

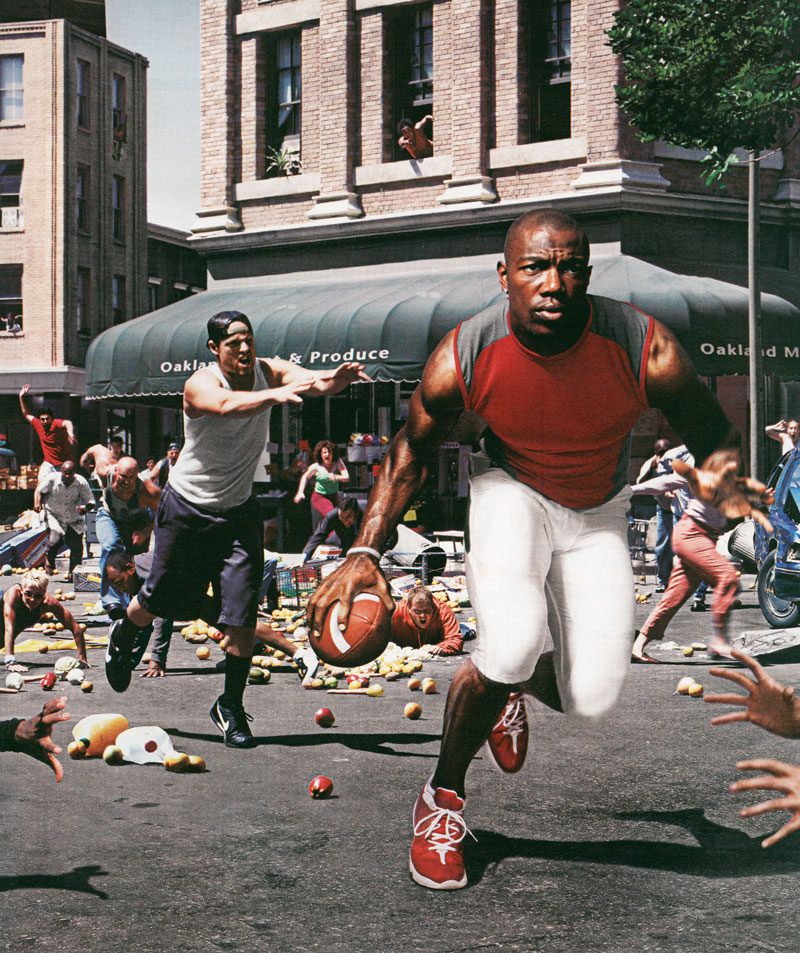

Hank Willis Thomas, How to Market Kitty Litter to Black People!, series: Unbranded, LightJet Print, 2005/2006.

SL Your series Strange Fruit and Branded link contemporary sports and advertising with the history of slavery. While basketball is frequently celebrated as a ticket out of poverty to fame, wealth and glory, these pieces suggest that the celebration of the black male body’s physical prowess in contemporary commercial culture is still tethered to this long history of exploitation—generating vast wealth that does not benefit the laboring body in view. I was hoping to draw you out a bit on how you think of this connection.

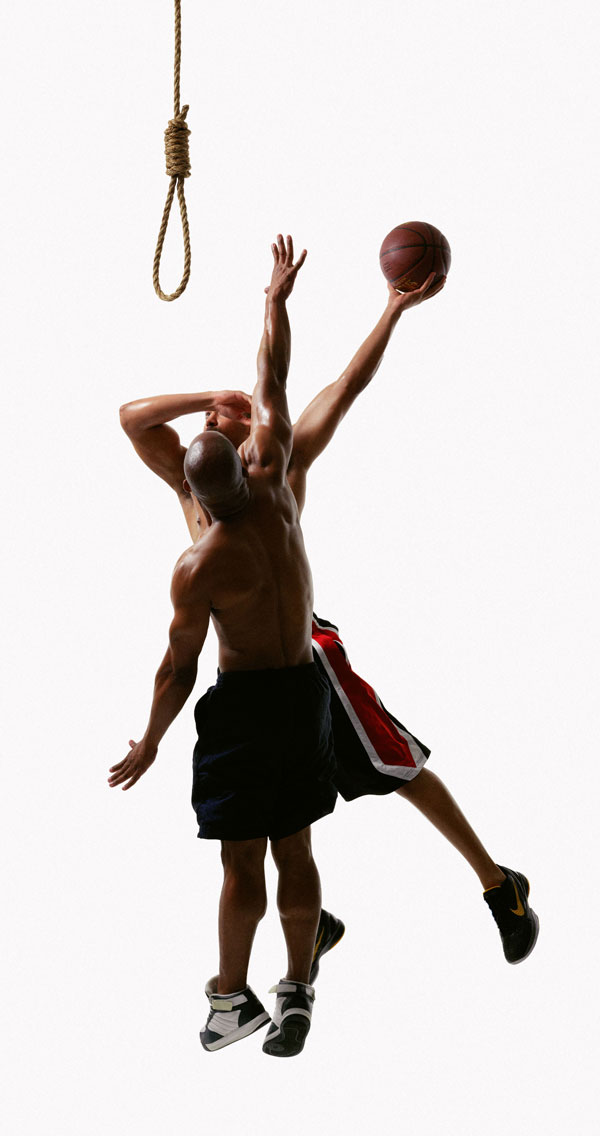

HWT The B®anded series definitely deals a lot with slavery and commodification of the black body then and now. I don’t see anything about slavery in Strange Fruit though. That’s part of the problem. It’s title, Strange Fruit, is a reference to the poem written by a Jewish American school teacher, Abel Meeropol. The poem was about Lynching and made famous by the singer Billie Holiday. The other works in that series speak about the sharecropping and whipping posts, which were very much 20th century practices. This is about exploitation, but also about spectacle. I think we too often conflate lynching and sharecropping with slavery. They are definitely connected but very necessarily distinguishable. Black bodies were spectacles in slave markets and on lynching trees and whipping posts. They are spectacles in the NCAA, NBA, NFL drafts and combines. Their ancestors may have worked the cotton and tobacco fields that later became football fields. Their ancestors may have been lynched. I am really trying to draw people out to talk about these very likely possibilities, so that we can think more critically about the present moment. Exploitation is what our country was founded on. It’s the american way. We should be more upfront about it. The NCAA is a multi-billion dollar business built primarily off of the free labor of descendent of slaves. What a bargain!

SL Advertising and media representations have proven a very fruitful ground for artists to appropriate and provide commentary on. Recent legal battles have unfortunately illustrated that artists can face severe legal retribution for adopting these image sources. Have you run into any copyright problems in your practice?

Hank Willis Thomas, The Liberation of T.O.: “I’m not goin’ back to work for massa’ in dat darned field!”, series: Unbranded, LightJet print, 2004/2005.

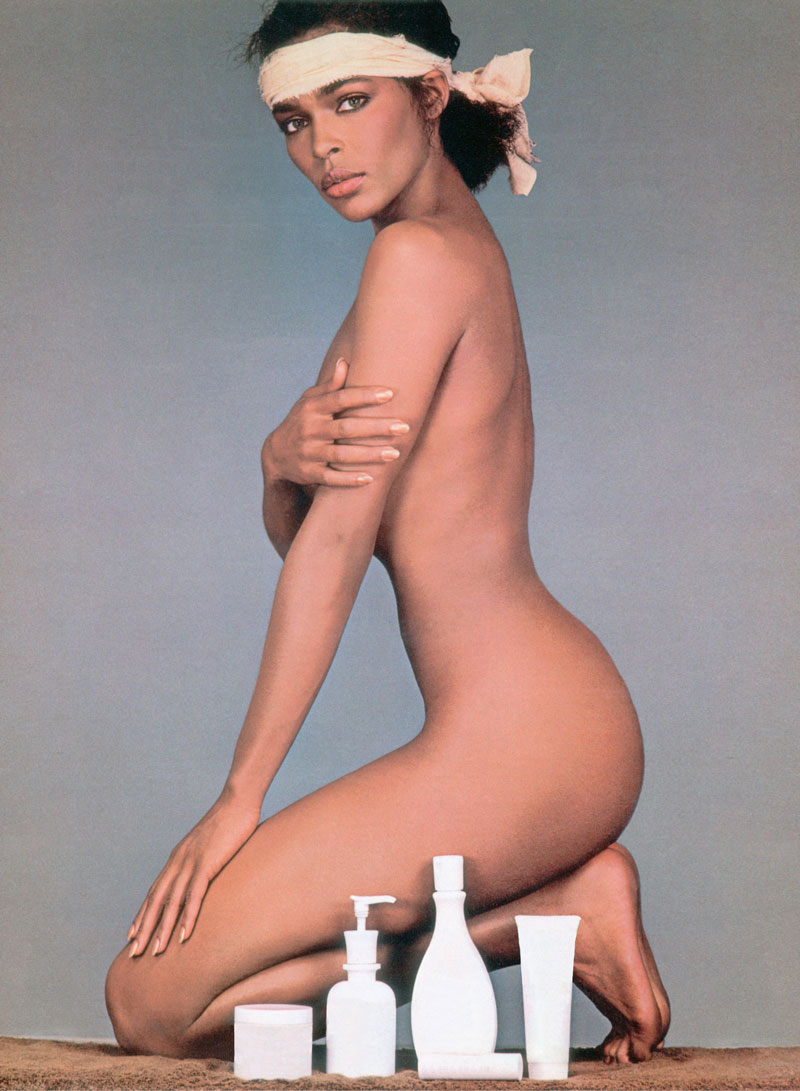

Hank Willis Thomas, Your Skin Has the Power to Protect You, series: Unbranded, LightJet print, 2008/2008.

HWT Not yet. But I don’t just do it for the sake of it. Maybe that’s the difference. Who wants to talk about how their copyrighted images might be perceived as racist? What trumps what? Race is kind of a third rail. A lawsuit could really raise consciousness about the problematics of copyright law and exploitation/representation of black bodies in popular media.

SL Your work is interesting to me in part because it really highlights the centrality of branding today. I think of branding as the process by which commodities become associated with feelings, but also vice versa: how affects become connected to consumables. These days branding not only applies to products, but also to institutions and people. The constant imperative to sharpen one’s own brand no doubt also penetrates the art field that is very dominated by such market logics. Do you find that you also struggle with the artworld’s compulsion to reduce every artist to a set of recognizable characteristics?

HWT The best thing about the art world is that anything goes. The worst part about the art world is that I don’t get it. Some people can see the matrix. I’m not one of them.

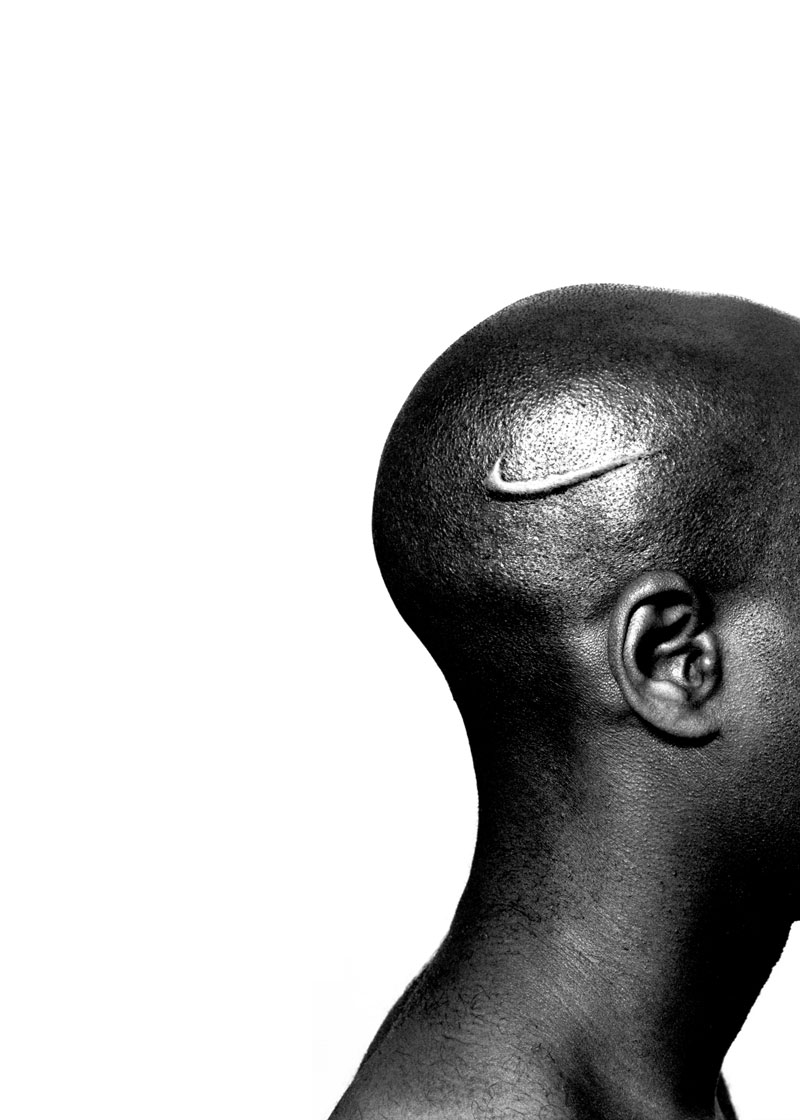

Hank Willis Thomas, Something to Believe In, series: Unbranded, LightJet Print, 63.5 X 50 inches, 1984/2007.

SL Your work could be interpreted to attest to the idea that advertising does not just tap into intrinsic identities, desires and emotions, but that it actively works to create those identities, desires and emotions for us. This is a bleak picture, of course. Is it one you subscribe to? Are we more complex and capable of resisting such interpellation than advertisers count on?

HWT It may sound trite, but commercialism is the new religion. We are all believers. Even the most radical of us. If you don’t believe in commercialism, you have to create your own non-commercial brand and market it. It’s not propaganda anymore. It’s just another ad. There are challenges that come with that, but also benefits. Barack Obama clearly had the most successful advertising campaign of all time. In three years he went from being completely obscure to being one of the most powerful people in human history. All he needed was discipline and a good brand strategy. What a bargain! He got my vote! Twice.

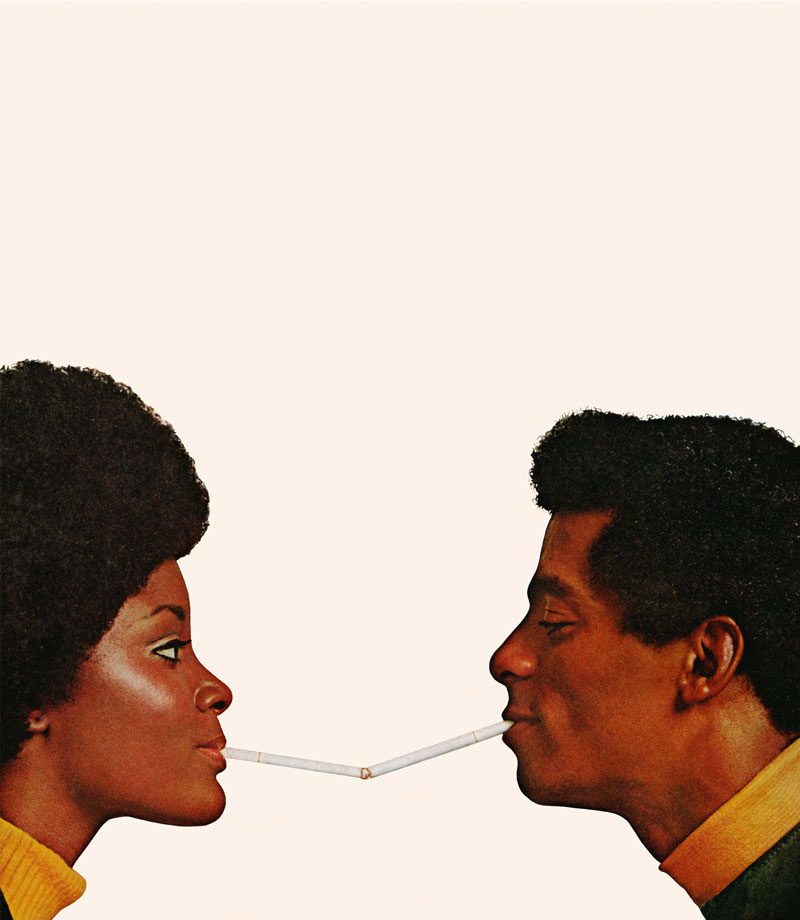

Hank Willis Thomas, Why Wait Another Day to be Adorable? Tell Your Beautician “Relax Me.”, series: Unbranded, LightJet Print, 1968/2007.