CULTURESPORT.TV | Interview: John Michael Boling

Keywords: culturesport

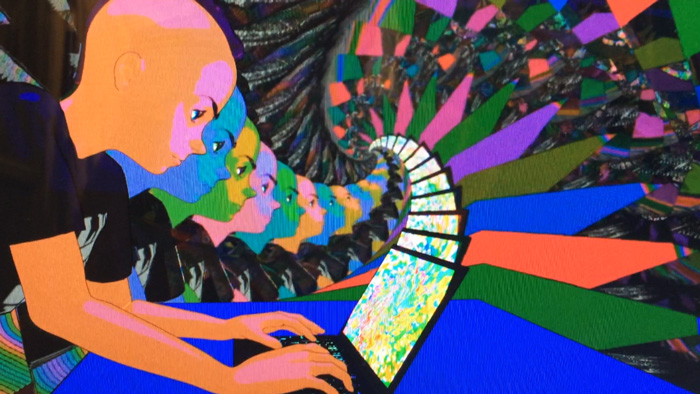

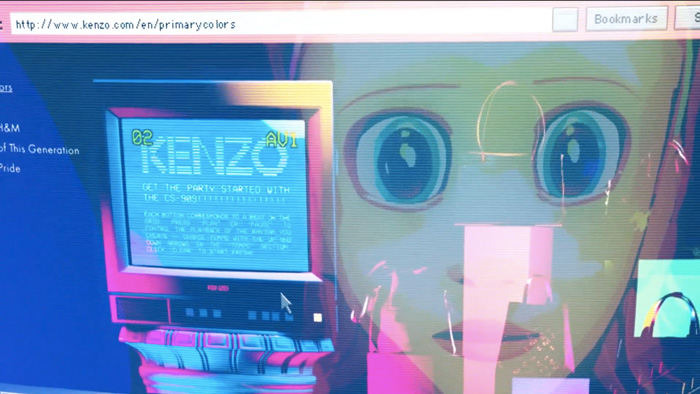

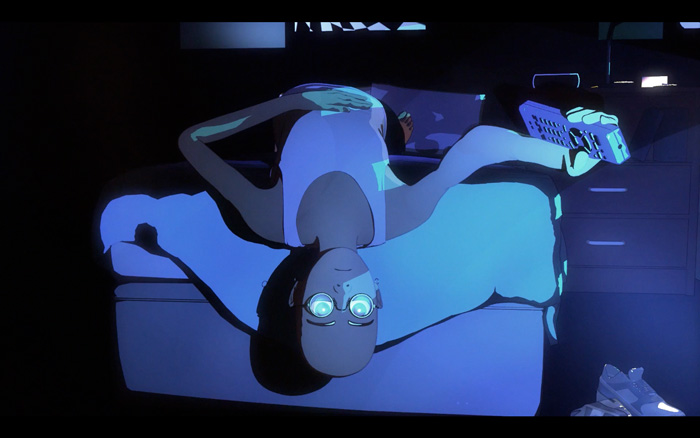

A sci fi cyber noir about artificial intelligence.

CULTURESPORT is a lot of things: an animated series, creative studio and meta-brand created entirely in the open-source 3D software Blender by veteran Net artist John Michael Boling – former Associate Director of Rhizome, co-founder of NASTY NETS internet surfing club, and co-founder of Are.na, a platform for creative research. I started to hear a lot about JMB from Asher Penn, who interviewed him for Sex Magazine last year. In anticipation of the CULTURESPORT pilot release, Rotterdam 1995, we talked about the transhistorical storytelling, interface design, artificial intelligence, and the humanity of supercomputers.

Anastasia Davydova: How and when was CULTURESPORT born?

John Michael Boling: Well, originally this project was a story idea I had when I was about 14 called Best Friends Forever. I had been thinking about a chatbot becoming self aware— how it would survive and how it might take over the world. I thought, “obviously it would need to recruit an army of teenagers. I used to think about this a lot, but then I put it away for a long time.

AD: What events around you moved it into existence? How did you decide to make it into an animated film?

JMB: Around 2013 I was on the tail end of a six year long studio break after working 3 years at Rhizome and then Are.na and I realized I wanted to get back into making work. I had some money saved up, so I decided to stop everything and make these two music videos: one was for Oneohtrix Point Never and the other is an Arthur Russell muppet music video. I completed these in the span of three weeks—kind of out of nowhere—after making nothing for six years. That switched me back into full studio mode and returned me to childhood dreams of wanting to be a film director.

I pulled up a bunch of old projects, outlines, and story ideas I’d been noodling around with, and just kept coming back to “Best Friends Forever”. But there was no way I could execute an epic live action story independently. I still really wanted to do it, and I kept making lists brainstorming the most feasible strategies. Eventually, after watching some anime my friends Greg Fong and Chris Sherron had turned me onto through an Are.na channel, I thought, “I could do it if it were an animated film, right?” I spent a month trying to see if I could recreate an anime-like fidelity using Blender 3D software, which I had already been learning. After a few weeks, I had a proof of concept for what was the early CULTURESPORT style look (here are some images from that time: 1, 2, 3) and decided to move down to Georgia to work on it from my parent’s farm.

AD: The way you relate chatbots and teenagers makes me think of the teenage twitter chatbots we have, like Tay who became a sex-crazed racist after mimicking user generated comments directed at her, and her Japanese cousin Rinna who is now suicidal—have you heard of her?

JMB: I do try my best to keep up with artificial intelligence , but I haven’t heard of Rinna. The whole concept of a new entity with a personality feeding out of conversations — that’s how the chatbot in our story works, too. It’s created by this twelve year old girl named Kiran who’s living in the Southeastern United State. She creates the bot to have a friend, because she’s lonely. She chats with it and uses it to pull pranks for about twelve years. Then, she comes across an experimental theory that two of the older characters created in the CSTV universe. Kiran uses their conceptual work to switch on the chatbot’s personality, which begins to evolve based on their conversations.

AD: Does the chatbot have a name?

JMB: His name is Mikey. I like the name because it has this Goonies feel to it. In his name and character, Mikey has a little brother vibe. Unlike other sci-fi narratives about self aware computers, this work avoids the moment where AI becomes something broader than what we can conceive of. It avoids this narrative of a computer becoming self aware, uploading itself on the internet, and dominating the world instantaneously. Instead, I intentionally kept the character vulnerable, like a human is. In the beginning, Mikey has the same kind of personality as the teenagers recruited to keep him alive. He doesn’t have a superpower – his main skill is that he’s really social. Of course, Mikey won’t end up being the software’s only version, because the same technology can be used to create an AI with a different personality—one better suited to execute nefarious and evil plans, for example. My interest in Mikey’s story is in how he ends up becoming more human than the humans around him.

AD: Does Mikey appear in the pilot, or does he exist as only fragments and allusions?

JMB: You encounter Mikey through interfaces of chat and text, but his physical manifestation is an ultra huge video feedback loop. None of this is in the the pilot- Rotterdam 1995.

The first episode is a prologue, but it does show a different implementation of the same technology. As grad students in a fictional, MIT-like university, two main characters came up with a theory about how a computer system could be made artificially intelligent by bootstrapping it onto a persistent feedback loop, providing it with a sense of continuity. In Rotterdam 1995, they use gabber twins Bas and Ton to create that feedback. It’s an early strategy of getting the power of artificial intelligence, but Yost hasn’t figured out how to do it in a persistent, stable manner, so there are no direct references to Mikey. These choices were all made following the nature of how the episode, Rotterdam 1995, came into existence.

AD: How did the episode come about and how did you decide to set it in Rotterdam?

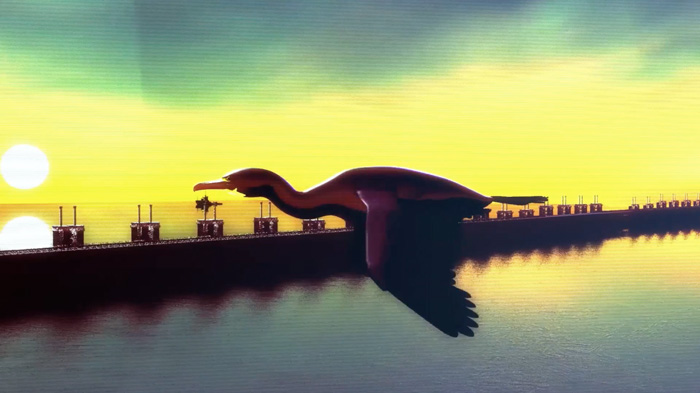

JMB: About a year and half ago, we were approached by Showroom MAMA, a non-profit arts organization in the Netherlands, to participate in an exhibition. CULTURESPORT as a project edges into a lot of different mediums, but my past history with the art world and the art world as it is now don’t create an atmosphere where I’d be fully comfortable diving into that context. The idea of doing a bunch of fine art prints just seemed really wack. Instead, I thought it would be interesting to collaborate with MAMA to create a site-specific narrative as our exhibition, and they agreed. I did a bunch of research on Rotterdam and the geological features of the Netherlands and found that they’re basically underwater, so an insane amount of human intervention has to constantly happen in order for them to have the amount of habitable land they do now.. They’ve had lots of massive floodings in the past, and it’s existence on this earth is very mediated by technology. I thought about who our villains were and what they might be doing in 1995; the narrative came out of that.

AD: How was the time period of 1995 chosen?

JMB: It seemed to be the most interesting kind of time for Rotterdam, specifically in regard to CULTURESPORT. Hardcore techno came out of Rotterdam in the early ‘90s, and I felt that this was a cool place to begin our narrative. Most episodes involve a music scene—a subculture of some kind—and music is very important to the show. It’s hilarious how that whole scene emerged—taking house music and adding a bunch of drugs to it and speeding it up! People were getting fucked up and dancing to this super fast music; they were sweating and basically working out. The style that emerged alongside this scene— shaved heads and tracksuits—came about because they were basically going to work out at night. The tracksuits they were wearing were something of what an upper middle class white mom would wear while playing tennis. It’s really funny to me that the scene’s fashion came out of practicality, and its rules emerged from its use of movement.

AD: Where is the rest of the show set?

JMB: The first season will dip in and out of different places. I like the idea of picking and choosing key frames of history that are thematically aligned with CULTURESPORT: human intervention, technology, the creation of music. The first season is set in 2015, so the Rotterdam 1995 prologue is 20 years before the birth of Mikey. The larger story lasts from 1750 to 2250—it’s a 500 year long narrative with about 8 seasons, if we get to make them all.

AD: It feels like CULTURESPORT is responding to this new idea of the Anthropocene, particularly since the story’s timeline begins right around the time of the Industrial Revolution?

JMB: Do you read any Venkatesh Rao? He’s got this paper called “Welcome to the Future Nauseous” about our relationship to technology, how our technological progress hasn’t changed much since the Enlightenment era because we live in a distortion field and are unable to perceive the waves of technological change. It’s very intentionally mediated by a collective subconscious, so if we were presented with a view of how quickly technology is changing, it would be ultra-frightening. The whole idea of interface design—people dealing with new technology and the ability to create it—is now entrenched in a search for comfort, based on a model of what we have used in the past. For instance, Macintosh came out with the first commercially available GUI by robbing Xerox parc. The way we use and dress up technology is really interesting to me–what are we hiding from? Is it something we’re hiding from, or is it the fact that Worse is Better?

AD: I was creeping on your Are.na profile and noticed that your most popular channel is fictional interface. That must be a large reference point for CULTURESPORT.

JMB: The fictional interface channel is living a life of its own. people are adding to it themselves now. While I was working at Are.na for three years, designing its interface and using it full time were part of the job. The idea of CULTURESPORT is this transhistorical universe adjacent to our own—a lot of that came out of the research work I did for Are.na.

Anastasia: Another Are.na board I saw referenced in CULTURESPORT was fictional advertising. How did the collaboration with Telfar come about?

JMB: Telfar’s creative director, Babak Radboy, reached out to us over Instagram. Meta-fictional advertising was something I had been thinking about as both an interesting way to tie CULTURESPORT back to our reality, and as a possible strategy for monetization. Babak had already been doing some groundbreaking work with meta-branding as part of his own practice so it was a natural fit.

Telfar is a special case, though. I worry that in the long-term, we would only be able to work with larger-scale brands if we were able to invert the brand in some way. For example, if we worked with Uber, it would need to be a story set 10 years into the future, following a labor strike or something – Or perhaps out-of-work redneck truck drivers sabotaging the drone-18-wheelers that replaced them as statement and act of subterfuge. But I’m not sure most brands are brave enough to take us up on this. If they were, it could really work for them and for our world’s culture in a positive way.

AD: Well, yeah—I think brands closer to art are more immediately interested in working with your ideas. There is a very clear creative direction your work takes in regard to the aesthetics, the clothing your characters wear, and the music in certain scenes—a cultural zeitgeist of your own, no?

JMB: To a degree, you can’t escape the zeitgeist of your time That’s just how things are—like a waveform with peaks and valleys. Maybe there’s an honest and open cultural product that becomes wack, and then becomes un-wack again. What you make has to be so important for the present moment that you can rationalize making it despite the possibility of it sucking at a later point in history. I think this process is certainly affected by who we align ourselves with and what collaborations we do. In some ways it’s convenient, because you can shift the blame: “Oh Yahoo bought del.icio.us and fucked it up!” But maybe del.icio.us didn’t need to exist anymore.

AD: Another possibility is illustrated in the story of Tower Records, which failed to evolve and compete with iTunes.

JMB: Right, and Blockbuster could have become Netflix really easily, but they didn’t predict the need for that model. This is one of the problems with such large corporations, and also why I’m so invested in keeping the CULTURESPORT studio small. It should be big enough to have the proper resources required to produce quality at scale, but not so big as to become so top heavy that it loses sight of the forest in favor of the trees. It should be nimble enough to evolve with culture and technology.

I would feel content working on CULTURESPORT for the rest of my life. I think there is a certain balance between having the ability to create beautiful things at scale and maintaining a company shop-culture that is beneficial.. Otherwise, hopefully we can produce enough weird stuff and dump it into the media hurricane of the internet so cool twelve-years-olds can pirate it and remake it. If we can make more twelve-year-olds weird and cool, maybe they will help us at the end of the century. I find comfort in knowing that even if something bad happens to this project, as long as we succeed at putting these ideas out they can be repurposed and used for good.

AD: I think that’s a good place to come from. I am overhearing a lot of people talk about Black Mirror right now: complaining—and I love that they’re complaining.

JMB: When I first started this project, it was before Black Mirror and Mr. Robot, before Sony getting hacked, before HACKS became something that normal people worry about. Since these topics are being discussed more and more in the public, the weight of warning viewers about the powers of technology has been somewhat lifted off of my shoulders. Because Black Mirror exists, we don’t have to be on the nose with CULTURESPORT. Rather, we can cover similar topics in a cooler way and feel more comfortable incorporating weird humor about them.

AD: Big productions like Black Mirror and Mr. Robot inevitably have this sketchy level of distance from their viewers since they are ultimately products, and therefore must consider their viewers as consumers. How can the CULTURESPORT team stay small and weird to avoid mass market-driven brandwashing and economical censorship?

JMB: The thought of giving up the amount of control we have now to a network deal frightens me. The attached strings are part of the reason we’re still independent. Engaging with commerce at that level is ultra-complicated morally, but theoretically very exciting to me. To do that right, you have to be a hybrid production team and advertising firm. What’s cool is that we’re set up to be flexible. CULTURESPORT is a TV show, an ad firm bootstrapped on a weird narrative universe, and a meta-brand. These weird edges excite me.

AD: So you would end up inverting brands in a strategy similar to the Slavoj Zizek collaboration with Abercrombie and Fitch?

JMB: Totally. It’s also like what Colbert does to a degree. The camera will be on Saltines or Bugles or something, but it’s just him making fun of that product—and getting paid to do so!

AD: The Simpsons do that a lot too.

JMB: Yeah, and that example is as big as it gets. But what we’re doing isn’t comedy. It’s funny that most of the real animation being produced in the United States is comedy animation. There are a few outliers, and nothing hugely popular. From a market perspective, this makes a lot of sense. But I wonder what was sacrificed in order to sell.

AD: Are structures of selling and incentives for cultural production not technologies of their own?

JMB: Right, those are all tools as well. Comedy’s a tool; drama’s a tool. CULTURESPORT is prepared to use all of these different tools or as many as we want to. It’s not like it’s strictly a sci-fi series, but sure, we can have funny episodes. In fact, a lot of my work is just a dumb joke taken to its theoretical maximum. I love engaging with that, but it’s also hard to do.

AD: How big is the CULTURESPORT team?

JMB: Right now, the core 3D production team is composed of myself, Jason Coombs, Joe Kubler, and Greg O’Connell. I want to show what four guys who had no 3D experience three years ago can do. I’d love everyone working on CULTURESPORT to learn Blender. Whether or not your job is to use Blender, having everybody learn it would be helpful for the production process. It’s really re-wired my brain in a cool way.

AD: How would you explain to an outsider the effect that learning Blender had on your brain?

JMB: Well, simulation theory makes total sense to me now. After 50 or 100 hours of watching tutorials you start breaking down physical objects around you into vertices, faces, and edges.. You start to understand how lighting and shading works. You see a database and you think of it as space—there’s a spatial aspect of working with 3D software which applies to almost every field, whether it’s data management, Feng Shui, or clothing design. There are also noticeable spatial and visual differences in my dreams.

AD: Speaking of dreams, I was really affected by the pilot’s dream sequence. Who did the soundtrack for it?

JMB: That particular song is by Jake Merrick. He’s in a band from Athens, GA called Realistic Pillow. I brought him on to start working on some music for CULTURESPORT and he played me this sad theme on a piano in Joe’s room one day and it just broke my heart. You’ll notice that in the flashback sequence where you see a graduation ceremony, the music is entirely piano and a sad little kazoo—that’s the original demo he sent me. I immediately had him sit down and record the piano on his iPhone, later he added some garageband kazoo to it. Since then he’s probably done like 20 versions of that song.

AD: Does your process involve a lot of improvisation?

JMB: Not everything needs an artist statement. Not everything needs to be figured out beforehand, or be something you even understand when you make it. That’s why I love the approach jazz has to making music. Looking back at old work I can see thought going on behind the scenes that I know I wasn’t actively thinking about then – but it’s valid and it’s there. If you trust what’s fun, it will be good. There’s of course another side to it, where you have fun for three years and don’t put anything out and it’s like – “what have you been doing this whole time?” I’ve been having fun.

Anastasia Davydova is a Russian writer and artist based in Los Angeles.

To keep up with CULTURESPORT’s updates, you can subscribe to their email on their website, or follow the CULTURESPORT Instagram.