Khaki Gone Tiki

Keywords: banana republic, british cavlary, cannibalism, casual fashion, cuba, duke of kent, duke of wellington, fashion history, fashion theory, great britain, hawaiian shirt, khaki, khaki fashion, khaki history, khakiism, king george III, maori, margaritaville, mayflower, military costume, military fashion, napoleon, old navy, queen victoria, rachel lord, raging waters, republican, south pacific musical, spanish american war, stereotypes, tahiti, the navy times, tiki doll, tiki exotica, tikiism, us navy, victorian era

Rachel Lord on Queen Victoria, Tiki culture, and the lesser-known origins of the technology we now call Khaki

It is an inalienable right of every man, woman, and child to wear khaki. Looking, acting, and ultimately being Prep is not restricted to an elite minority lucky enough to attend prestigious private schools, just because an ancestor or two happened to arrive here on the Mayflower. You don’t even have to be a Republican. In a true democracy everyone can be upper class and live in Connecticut. It’s only fair.

—The Official Preppy Handbook, p 1.

Informal Empires

Khaki is a phoneticized loan-word from the Hindi-Urdu-Persian : ![]() (khak) meaning ash, or dust. The ee-sounding “i” is an added suffix signifying khak-iness; hence, khaki, by its entomological definition means “having the quality of ash, or dust.”

(khak) meaning ash, or dust. The ee-sounding “i” is an added suffix signifying khak-iness; hence, khaki, by its entomological definition means “having the quality of ash, or dust.”

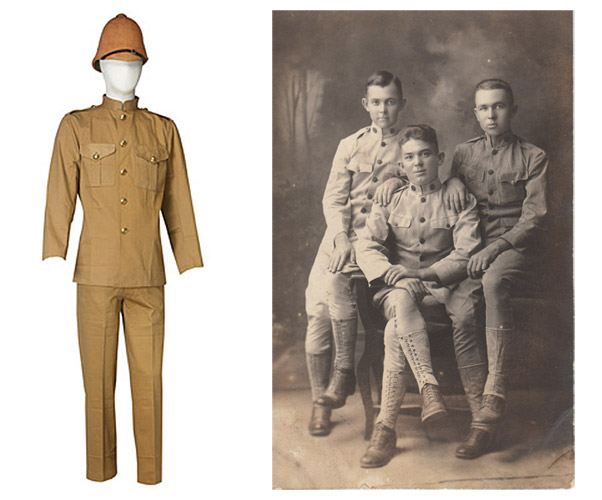

The backbone of business-casual: appropriate when jeans are not—without seeming fussy, khaki is formally un-formal. But, while developed in a similarly IFCHIC fashion, khaki was a Victorian military breakthrough. A technology, first and foremost, that gave the “Informal Empire” of Great Britain her second wind.

On June 20th, 1837, at the age of eighteen, Queen Victoria ascended the throne of Great Britian. She, the daughter of Prince Edward, Duke of Kent and Strathearn—fourth son of King George III, oversaw, over the ensuing sixty-four years of her reign, an era of unprecedented British imperial rule.

The Victorian era coincides with a time of relative domestic peace in Europe known as Pax Britannica—a period begun by the defeat and subsequent disintegration of Napoleon’s Army at the Battle of Waterloo (1815) by the forces of the Seventh Coalition1 under the command of Lord Arthur Wellesley the Duke of Wellington, and ended with the outbreak of World War I (1914.) Great Britain, now the preeminent Western military power due to the strength of her naval forces, capitalized on this period of unprecedented domestic security in Europe by diverting attentions elsewhere.

Investing in the entrepreneurial spirit of maritime trade, Queen Victoria launched a series of “small” wars against an unprecedented range of new foes: Abyssinians, Afghans, Afridis, Arabs, Ashantis, Australians, Baluchi, Bengalis, Boers, Bunerwals, Burmese, Canadians, Chamlawals, Chamkannis, Chinese, Chitralis, Dervishes, Egyptians, Fingoes, Gaikas, Galekas, Ghazis, Hadendowahs, Hassansais, Hottentots, Hunzas, Indians, Isazais, Japanese, Jowaki Afridis, Kaffirs, Khudu-Khels, Kodakhel Baezais, Kostwals, Lushais, Madda Khels, Mahrattas, Mahsud Wazirs, Malays, Mangals, Maoris, Mashonas, Masais, Matabeles, Mohmands, Orazais, Pathans, Peraks, Persians, Punjabis, Russians, Sepoys, Shinwaris, Shiranis, Sikhs, Somalis, Sudanese, Tibetians, Utman Khels, Wazaris, Zaimukhts, Zakha Khel Afridis, and Zulus, to be specific.2

In this they were unremittingly directed by the Duke of Wellington, whose stern dictates shackled the British Army to the conventional methods used in the Napoleonic Wars a half-century prior, half-a-world away. He vehemently insisted the musket to be a far superior arm than the rifle, and that the solider fought best when encumbered by heavy accoutrements, uncomfortable chokers, suffocating stocks and ill-strung knapsacks.3 When confronted with the realities of non-conventional, guerilla-style warfare in harsh climates against an ever-changing enemy, their primary issue was their inflexibility.

Throughout the Victorian era, British cavalry, in particular, were consistantly handicapped by tight and unserviceable clothing, slippery saddles, and unsuitable arms. Dr. Andrew Fergusson, Inspector General of Military Hospitals, ridiculed the “…foreign fooleries so laced and looped and braided of the Hussar; the woman’s muff upon his head with something like a red jellybag on the top and the richly decorated pelisse waving empty, sleeves and all… an abuse and prostitution of the English character.”4

In the Duke’s own words on his approach at their dispatch at Waterloo:

“Our officers of cavalry have acquired a trick of galloping at everything. They never consider the situation, never think of manoeuvring before an enemy, and never keep back or provide a reserve.”5

This attitude causes a few heads to roll in the Kaffir War of 1852, when the 12th Royal Lancers found themselves under constant assault of a superior number of Basuto riders armed with battle-axes and assegais. The cavalry were encumbered by overalls so tightly strapped that a remount was possible only if a comrade were at hand to hold their saddle in place.

And so, on May 21st, 1858—a day which did not go down in infamy—the true Informal Empire is heralded with an order from Her Majesty’s Adjutant-General:

“With the concurrence of the Government, the Commander-in-Chief is pleased to direct that white clothing shall be discontinued in the Regiments of the Honourable Company’s Army; that for the future the summer clothing of the European soilders shall consist of two suits of ‘khakee’.”6

“Khaki” has become term for chief petty officers in the US Navy, due to the historical color of their uniform. Khaki first served the US Army in the Spanish American War of 1898 and has been the semi-formal service dress for naval operations and occupations in the tropics for the better part of the last 113 years.

While the contested matter of the Spanish-American War was one of Cuban “independence” from Spain—American concern being sparked by the suspect sinking of the Battleship Maine in Havana Harbor—the ten-week war was won in large part due to a series of decisive US military and naval actions not in Cuba but in the outlying Caribbean and Pacific islands and waters. This earned the victorious Americans favorable accord by the terms of the 1898 Treaty of Paris. Not only did the US see to the fall of the remaining colonialist threat to American domestic and regional security, it acquired their regional colonial legacy as well. The US was granted temporary control of Cuba, and for the purchase price of $20MM, the United States acquired Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines—the future Pacific arena of World War II.

Service Dress khaki uniforms in the US Navy—widely seen in service from WWII through The Vietnam War—were dropped in 1975 by the Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Elmo Zumwalt in an effort to reduce the number of items in an officer’s sea bag. Then in 2007 Service Dress khaki was reintroduced to petty officers who welcomed the new semi-formal as a more practical alternative to Service Dress whites. The Navy Times, in an article announcing the new uniforms, called the design “a throwback” and sung the praises of khaki’s heritage, saying “by simply donning the khaki jacket…the chief or officer was set to walk into any situation requiring a more formal look—one that doesn’t require a complete uniform change into service dress blues or whites.”

Khaki Gone-Tiki

In lieu of exhaustive analysis of the myriad ways in which khaki achieved its civil sublimation, I will instead draw upon but one instance khaki-ganda: Rogers & Hammerstein’s film version of the musical South Pacific. For it is here that khaki becomes full-flegged exotica. Thanks to the swift economy of the duo’s stereotype-based approach, we need only look to one brief scene between two musical numbers to be inducted to the fetish of khaki and the cult of tiki.

Tiki is a remarkably versatile word in the Maori language. We Westerners are likely familiar with tiki: the carved figure, image, or neck ornament usually made of greenstone or coconut, mug, and carved in an abstract form of a human. Tiki, the verb, means: to fetch, proceed to do (anything), go (for a purpose), go and get, come and get. Reed’s Concise Maori Dictionary defines Tiki, the proper noun, as “the first man, or the personification of man.” In some narratives Tiki was the first man created, while other narratives say he created the first man. Tei Tetua, a Marquesan native and former cannibal cited by adventurer and author, Thor Heyerdahl (author of Kon-Tiki) in his 1934 book Fatu-Hiva – Back to Nature, describes Tiki as “God and Chief, he who led the ancestors to the islands where we now live.”7

In the 1950s and 60s, tiki-esque figures began springing-up on mantles and lawns across America. Martin Denny, the proverbial Tiki of exotica music (the sound of Tiki culture,) explains:

Between 1958 and 1960 many people displayed tiki in their gardens and organized Polynesian parties like luaus. They wanted to recreate a piece of Hawaii in their backyards, evoke the atmosphere of the South Seas…I don’t know who thought up this trend, all I know is that Americans couldn’t care less about the religious origins of the tiki.8

To the hardy folk returning from WWII, displaying a tiki was a declaration of religious (Christian) contempt.9 As they oft-not go much further into paganism, tiki and Tiki-style were to the G.I. Generation a profession of their alternation from Puritanical progenitors to something a bit more Catholic-confessional. Boomers had their hair, free love, and drugs; their parents: the Hawaiian shirt, an exotic fantasy of “free-style” love without the use of contraception, and mixed-drinks.

And cocktails are crucial, for if tiki culture in America can be said to be a cult of anything, it is a cult of drink. So, pull-up those chinos, Skip, and throw on your finest hibiscus. We’re going to a place called Tiki Ti. The bar: rattan. The floors: sandy. The drinks: strong as can be. And as of this April 28th, a full fledged…

Fifty. A mind-boggling thought for a war baby like me. Fifty is not ‘just another birthday.’ It is a reluctant milepost on the way to wherever it is we are meant to wind up. It can be approached in only two ways. First, it can be a ball of snakes that conjures up immediate thoughts of mortality and accountability… Or, it can be a great excuse to reward yourself for just getting there…I instinctively choose door number two.10

—Jimmy Buffet, A Pirate Looks at Fifty

Just Buffett

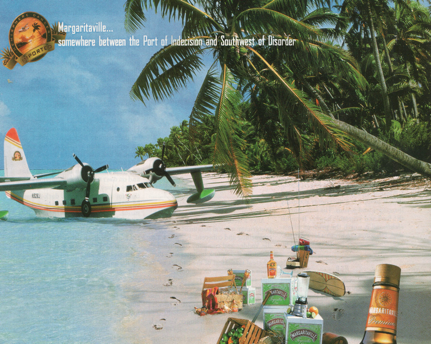

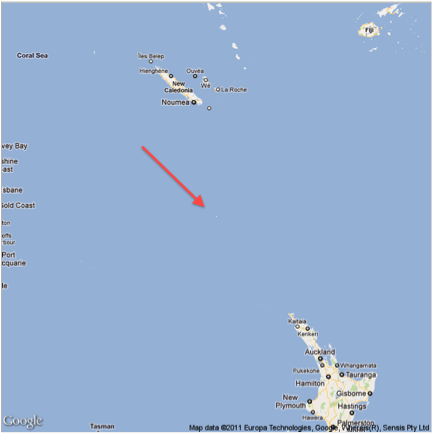

No one is more khaki than Catholic entrepreneur, performing artist, author, and aviator Jimmy Buffett. For not does he only wear khaki, he’s also totally tiki, and his khak-tiki heritage is nearly as old as khaki itself. Jimmy Buffet, was urged by descendants of South Fijian and Maori islanders who had encountered his name on posters promoting his Australian Tour in 1996 to visit the tiny and remote Norfolk Island. On his fiftieth anniversary heritage expedition, aboard his Grumman HU-16 Albatross seaplane The Hemisphere Dancer that resulted in his memoir, A Pirate Looks at Fifty, he said of the place, “There was this huge clan of Buffetts…they were all there.”11

BANANA REPUBLICS

BANANA REPUBLICS

Down to the banana republics

Down to the tropical sun

Go the expatriated American

Hoping to find some fun

—Steve Goodman

ON May 5th, 1891, John Buffett died on Norfolk Island, a British Overseas Territory. His fellow 3rd (4th, and, 5th in some cases) Pitcairners—transformed by means of libel spirits and topless, Tahitian women—turned the once brutish British penal colony into a “Pacific Paradise.” (National Geographic, October 1960) Not having read Tales of the South Pacific by James A. Michener, I’ll quote what Steve Eng did, in Jimmy Buffet: The Man From Margartiaville Revealed, calling Norfolk Island “a speck under the forefinger of God.”

Excerpt from “The Great Revolution In Pitcairn”

by Mark Twain, Atlantic Monthly, 1879

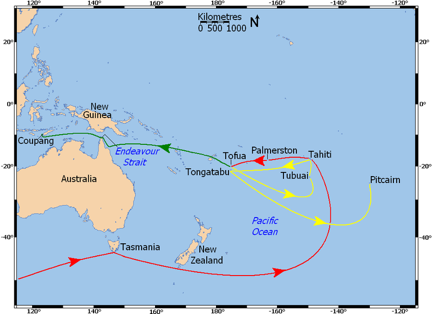

Let me refresh the reader’s memory a little. Nearly a hundred years ago the crew of the British ship Bounty mutinied, set the captain and his officers adrift upon the open sea, took possession of the ship, and sailed southward. They procured wives for themselves among the natives of Tahiti, then proceeded to a lonely little rock in mid-Pacific, called Pitcairn’s Island, wrecked the vessel, stripped her of everything that might be useful to a new colony, and established themselves on shore. Pitcairn’s is so far removed from the track of commerce that it was many years before another vessel touched there. It had always been considered an uninhabited island; so when a ship did at last drop its anchor there, in 1808, the captain was greatly surprised to find the place peopled. Although the mutineers had fought among themselves, and gradually killed each other off until only two or three of the original stock remained, these tragedies had not occurred before a number of children had been born; so in 1808 the island had a population of twenty-seven persons. John Adams*, the chief mutineer, still survived, and was to live many years yet, as governor and patriarch of the flock. From being mutineer and homicide, he had turned Christian and teacher, and his nation of twenty-seven persons was now the purest and devoutest in Christendom. Adams had long ago hoisted the British flag and constituted his island an appanage of the British crown.

* John Adams is Jimmy Buffett’s great, great, great, great, great, great, great, great, grandfather.

Footnotes

- Alliance consisting of the United Kingdom, Prussia, United Neatherlands

- Featherstone, Donald. Khaki & Red: Soldiers of the Queen in India and Africa. Arms & Armour Press, London, 1995

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Wikipedia.

- Featherstone, Donald. Khaki & Red: Soldiers of the Queen in India and Africa. Arms & Armour Press, London, 1995.

- Adinolfi, Francesco. Mondo Exotica: Sounds, Visions, Obsessions of the Cocktail Generation. Duke University Press, Durham, 2008.

- Ibid.

- Von Busack, Richard. “Tiki It to the Limit.” Metro http://www.metroactive.com/papers/metro/01.04.96/tiki-9601.html

- Buffett, Jimmy. A Pirate Looks at Fifty, pg. 9

- Eng, Steve. Jimmy Buffet: The Man From Margaritaville Revealed.

Additional Bibliography

Hyam, Ronald. Understanding the British Empire, Cambridge University Press, New York. 2010.

Bullock, Christopher. Britian’s Gurkhas, Third Millennium, London 2009.

Moraes, George M.. Mangalore, a historical sketch; Studies in Indian History of the ‘Indian Historical Research Institute,’ St. Xavier’s College, Bombay, Number 2; 1927.