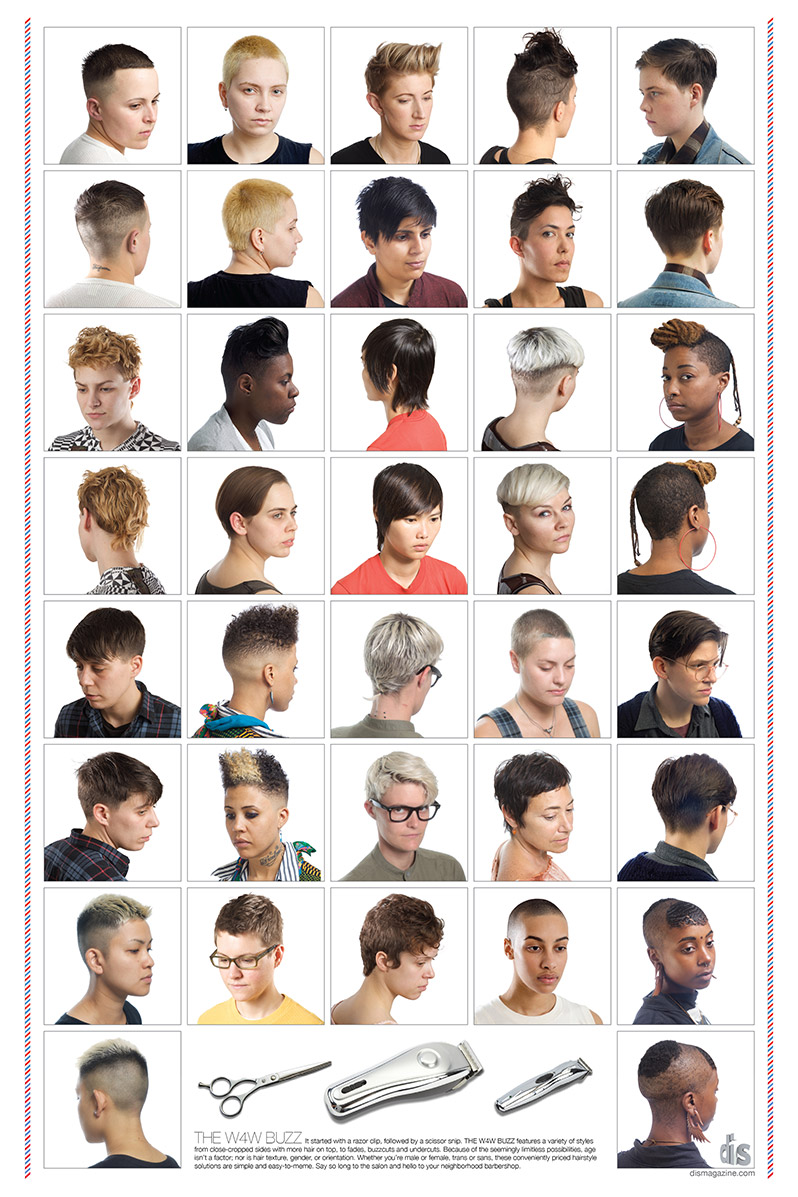

The W4W Buzz

Keywords: A Cyborg Manifesto, barber, brush, buzz, clippers, comb, crewcut, cuts, dis magazine, Donna Haraway, DYKE, Fashion, feminism, Gender Trouble, hair, haircut, hairstyles, identity politics, Judith Butler, Katerina Llanes, lauren boyle, lesbian, lesbian visibility, marco roso, queer, razor, salon, styles, W4W, women

Lesbian visibility barbershop poster by DIS and essay by Katerina Llanes

A HAIR PIECE

by Katerina Llanes

When in 1990, Judith Butler published her groundbreaking text, Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity, she had no idea the impact it would have on the foundation of queer theory—one that analyzed the construction of gender and heteronormative assumptions made about sex, performativity, desire, and identity. Now, 20 years later, the text remains a touchstone as we continue to muddle through our ambiguously gendered lives.

In the book’s post-preface, written nearly 10 years later, Butler clarifies some of the contradictions and misinterpretations brought forth in Gender Trouble. She acknowledges the emergence of new forms of gendering in light of transgenderism, transexuality, and new butch and femme identities offering, in her words, “evidence of a new kind of gender trouble that the text did not anticipate,” a gender trouble that her colleague, feminist scholar Donna Haraway, most certainly did.

Published in 1985, A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, Socialist-Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century introduced us to the concept of a cyborg—“a cybernetic organism, a hybrid of machine and organism, a creature of social reality as well as a creature of fiction”. This creature symbolized our union with late twentieth century bio-politics and acted as a utopian vision in a post-gender world. “The cyborg is a condensed image of both imagination and material reality, the two joined centers structuring any possibility of historical transformation.”

And while I wouldn’t say we’re fully there yet, the queer cyborg has developed in opposition to rigid masculine/ feminine doctrines to create hybrid genders: part alien, landscape, sea turtle, pencil holder, the cosmology of our identity extending deeper into the rays of the phantasmagorical World Wide Web. But with radical evolution comes the threat of market takeover. Our bodies are more sculpted than ever before by technological advancements and the conditions of mass cultural consumption. With this in mind, I would like for us to consider the queer female body in the 21st century, a body that exists both within and outside the limits of subversion and exploitation.

More than any other stylistic signifier, hair has become our window into lesbian visibility. The shorter the hair, the more visibly identifiable one becomes as a lesbian. While these assumptions can prove useful within queer communities as shorthand for lesbian cruising, we should be careful not to ground them in the world at large as they are often ill-founded and politically misaligned—re-asserting a gendered binary based on heteronormative codes, butch for masculine / femme for feminine. These gendered polarities often mimic heterosexual partnerships dismissing the existence of any gender in-between. Worse yet is the way in which the “femme” is rendered invisible by her lack of stylistic transition—context being her only mark as a lesbian—while the butch is propped up as the face of lesbianism worldwide. Both, in turn, exploited by the branding machines of late capitalist enterprise. Even drag, Butler argues in her follow-up book, Bodies That Matter: On the Discursive Limits of Sex, cannot always be deemed subversive. “Although many readers understood Gender Trouble to be arguing for the proliferation of drag performances as a way of subverting dominant gender norms, I want to underscore that there is no necessary relation between drag and subversion, and that drag may well be used in the service of both denaturalization and reidealization of hyperbolic heterosexual gender norms.”

In light of the dangerous pitfalls within what constitutes lesbian in/visibility, I would like to make a plea for the return to liminal gender, a queerness that falls through the cracks of polar identity and makes use of the limitless potentials of a cyber queer network. With the spread of the internet, our bodies exist now outside of a physical domain—comprised, instead, of composite images: a bird in a swing, plaid overalls, a gymnasium in Taiwan. We are both materialized and de-materialized, and it is precisely this ambiguity that will allow us to continue moving forward—shifting and gliding—into our present future.

The W4W Buzz Marco Roso and Lauren Boyle

Photography Marco Roso

Essay Katerina Llanes

Special thanks to everyone who participated.