Accounting for Race in Fashion, pt. 1

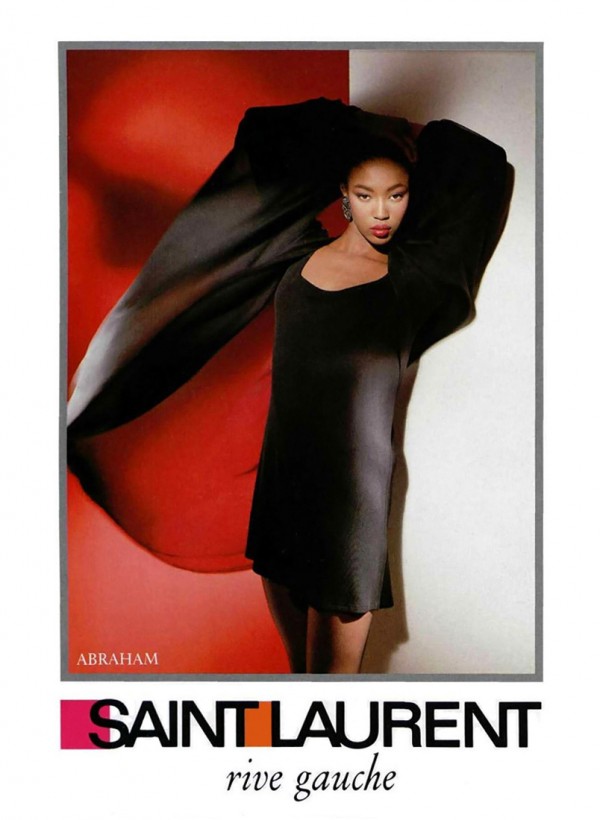

Keywords: anxiety, Bethann Hardison, class, Diversity, Fashion, fashion week, Iman, Jeremy Lewis, models, Naomi Campbell, Politics, race, Racism, runway, status

When it comes to race, fashion, for all its appreciation for poetic expression, has suffered a gross lack of elegance in dealing with it.

Race can be a perilous topic of discussion. It’s a complex weaving of personal, social, cultural, psychological, geographical and biological discourses that are as nuanced as they are impossibly obtuse. The slightest inaccuracy can be misinterpreted as the worst intention while an overt act of injustice can go completely overlooked. In politics and popular culture, where the reach is as broad as it is diverse, the discussion about race is often awkward and clumsy. In the world of maquillage pas cher fashion, a world that prides itself for its creativity and appreciation of the new, it is even more constipated. This however should be no surprise. Fashion, as it more or less exists today, was born from the need to distinguish class and status through dress at a time in European history when socioeconomic shifts made old standards and codes obsolete. The need to seasonally update your wardrobe to the prescribed mode of the moment became a mark of not only wealth but the correct taste, a taste level that marked you as one of the privileged few who could afford as well as care. And so fashion, rather naturally, became an extremely efficient system for making judgements and assigning meanings based not only on dress but overall appearance. When race enters the picture, loaded with the histories and prejudices that often come with it, fashion proves apt at codifying skin color, assigning it status and decreeing which hues and tones of flesh are and aren’t aspirational. And as the overused and under appreciated adage goes, fashion is a mirror of the times. What it reveals is as much a reflection of our dreams and desires as it is our limitations and flaws. And because of this ability to document the spirit of the times, accounting for race in fashion, no matter the peril, is important. Attention must be paid. To say that fashion is racist is besides the point, but when it comes to race, fashion, for all its charm and appreciation for beautiful if not poetic expression, has suffered a gross lack of elegance in dealing with it.

Last fall former model and now casting director Bethann Hardison teamed up with legends Naomi Campbell and Iman to form the Diversity Coalition; an activist group tasked with addressing racism in the fashion industry, specifically in model casting. The coalition brought industry wide attention to what they insist is a lack of diversity in the casting of designer’s runway shows. They sent out letters to each governing body of the four fashion capitals (New York, London, Milan, and Paris) explaining the apparent lack of “models of color,” citing that most casts have only a single “model or color” or none at all. It is a fair observation and a worthy issue to stir. Runway shows not only represent a designer’s truest and purest expression of their brand, they also represent aspiration. The all-caucasian cast of a leading and directional house will set a precedence for other brands and designers as well as other glamour-making industries (cosmetics, hair, jewelry, etc). And there is of course the effect on a global audience of consumers, men and women who casually observe, civilians you could say, who passively learn their beauty ideals from fashion imagery. The residual effects of such extreme racial bias is substantial. Of course, there is no racial sensitivity training required to become a designer and it is in fact a designer’s autonomous creativity that allows them to innovate and make the wonderful clothes we love them for. But to ignore and refuse these implications in the context of fashion, an industry that celebrates continual progress and gains much of its power by posturing itself as beyond or more forward than the status quo, seems counterintuitive. Modernism is a concept that is bandied about by designers each season to explain their collections. Fashion loves modernity, it swallows it up and asks for seconds even when its meaning becomes abstract and intangible. So in the world we live in today, where the United States of America has a mixed-race president and a black first lady, what could possibly be considered modern about an all-caucasian line-up of models?

Though the coalition’s letter makes a call for diversity, it does infer that some races are favored over others pointing out the prevalence of Asian models in runway castings (which some designers see as evidence that the coalition’s claims are unfounded). But to be frank, the coalition’s issue with diversity is targeted specifically at the rarity of black models. A quick glance through runway shows over the last several years reveals a disproportionately low amount of black models present. If we filter this observation through the idea that fashion reflects society’s values what does it then say about our popular perception of black identity, black bodies, and the black visage? Let’s consider the implications of blackness and fashion as it can unfold off the runway and in reality. Consider the two black teens who sued a luxury department store for being racially profiled, wrongly accused of credit card fraud, and accosted by the NYPD for buying designer accessories. Or, and to really add some gravity to the situation, consider the tragedy of Trayvon Martin, a teenager who was stalked and eventually shot to death for wearing a hoodie and being black in the wrong neighborhood. To believe there is no connection between society’s prejudice towards black people and how they manifest and register in our ideas of dress and fashion requires an incredible incredulity. And though Asian identities have been equally subject to racist generalizations and prejudice (from the characterization of the Japanese as human rats in the 1940’s to Mickey Rooney’s Mr. Yunioshi in Breakfast at Tiffany’s), it is a very different and far less damning history than what blacks have undergone. To conflate the two does not address the real issue at hand.

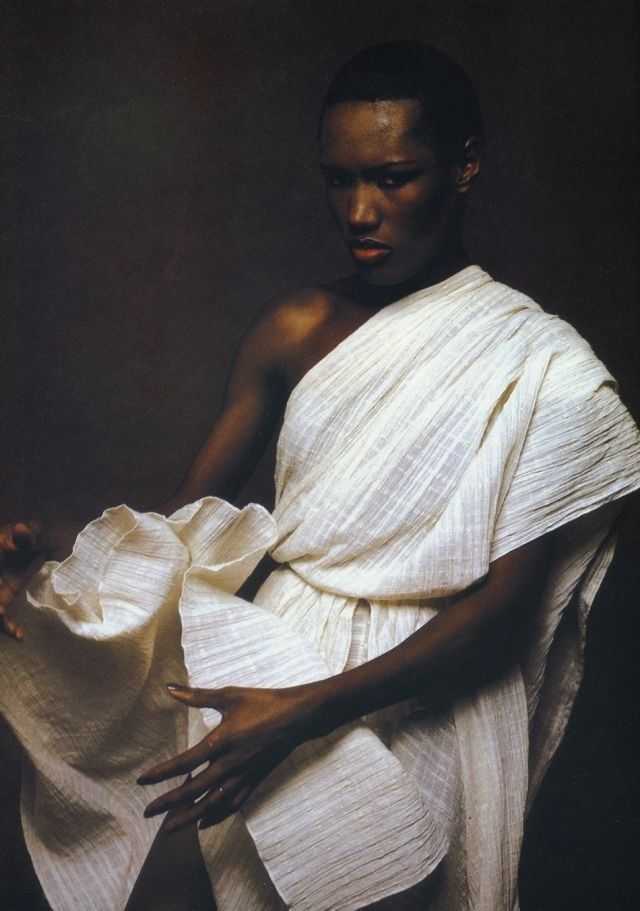

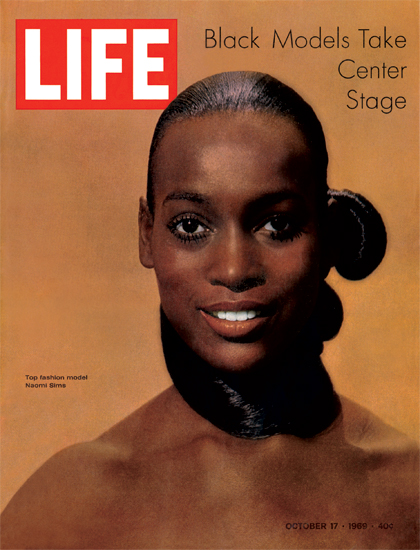

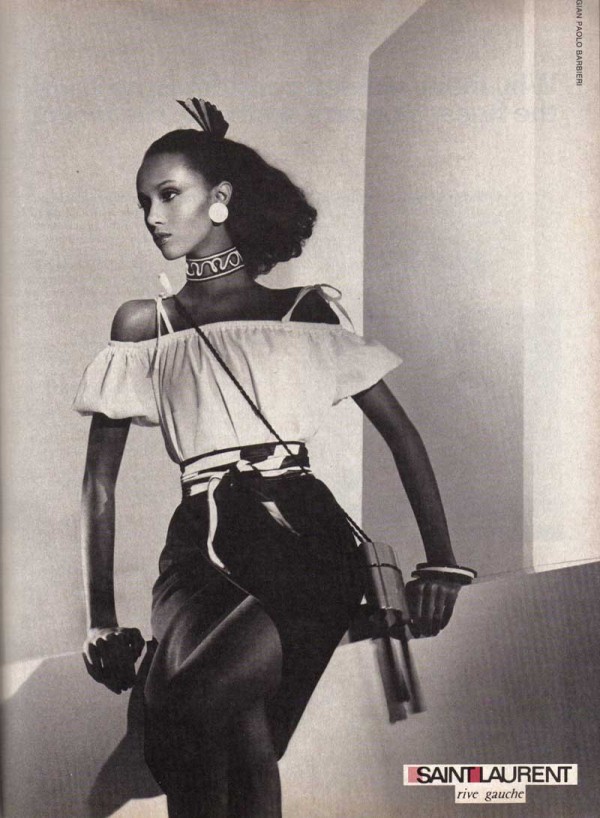

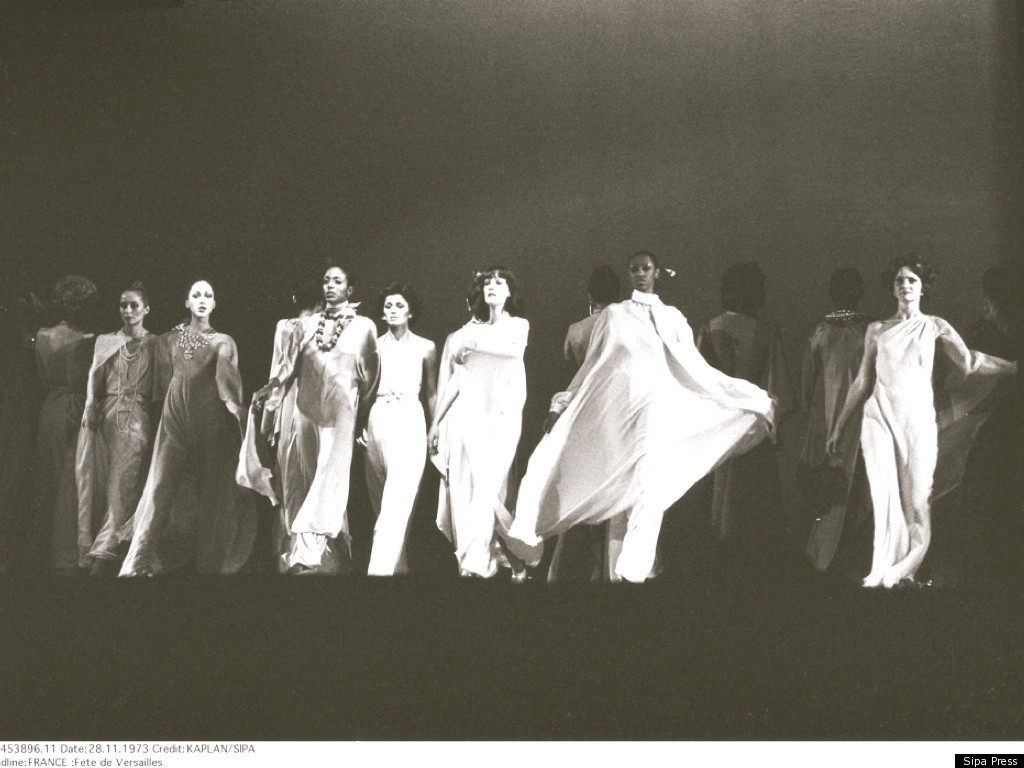

The representation of black identity and black features in Western visual culture and history is riddled with stereotypes, generalizations, and gross caricatures that go back as far as slave trading in the Americas. Black people throughout American and European history have been demonized, dehumanized and regarded as little more than clowns or animals: the minstrel, the mammy, the pickaninny, the golliwog, the coon, these caricatures have left a lasting and damning impression of black beauty and identity in Western culture. Even until the 1960’s, in the U.S., black skin marked one as a second rate citizen, or even worse, subhuman as Jim Crow laws forbade blacks to drink from the same water fountain, to attend the same schools, or even use the same bibles for swearing an oath in court as their white counterparts. Conditions however change drastically in the 1960’s with the civil rights movement and into the 70’s, the last era when black models were popular in high fashion. This is the time when Bethann Hardison emerged alongside Donyale Luna, Naomi Sims, Pat Cleveland, Peggy Dillard-Toone, Toukie Smith, and many others. These faces seemed to represent the Black is Beautiful mantra realized in full. In 1973, when an envoy of American designers showcased their clothes against a slew of French talents in Versailles, the black models that were brought represented a new paradigm shift in what modernism and beauty could mean. Yves Saint Laurent famously preferred black models, they held esteemed places in all the top shows as their beauty and their bodies were used to sell the most expensive clothes in the world. With black models being celebrated by the world’s most important taste makers it would seem that a centuries long history of discrimination bias would be undone. But something happened, from the 1980’s onward Black models began to fall increasingly out of fashion until you arrive at the present where they are few and far between despite that racial discrimination has, though arguably, decreased over the last few decades. Factoring in this context it becomes difficult to blame Bethann Hardison for her outrage with what is happening today, decades since her days as a model and a young woman when racial inequality was a far more hampering injustice.

The solution to the issue is no easier had in fashion than it is in the rest of society and politics but the ramifications are much simpler to understand. Many brands and designers will avoid black models because they fear their audience will find them difficult to relate to, a not unreasonable marketing decision. Designers who have been called on to cast more black models deflect blame to the modeling agencies for not supplying any, they in turn deflect blame to the designers claiming that they send only what their clients request. Progress won’t be had by assigning blame but by raising an understanding. And the understanding is quite simple: should you be an entity that stakes its reputation and business on being on the cutting edge, for being modern, for being on trend, for being forward, for being contemporary, for being fashion, to lack a diverse casting with no black models or “models of color” immediately marks you not as racist but as behind the times, out of fashion, démodé. Like moldy bread or rotten milk, curdled and sour, the stench of the obsolete ideals of a bygone era linger around your aura like the stinging cloud of formaldehyde leaking from a trussed up corpse. What bold vision of the new could you possibly offer? What forward gazing ability could you possibly hold? There is nothing chic about hypocrisy. Any good design or provocative brand message immediately becomes nullified, embarrassingly unbelievable and totally void of validity. This is what is to be understood and this impetus, if any, should motivate designers and brands to pay more attention to the images and identities they wield. But then again, one does wonder if there were more black designers acting as tastemakers would there even be such an issue with castings? And then that opens up a whole other discussion…