Behind, Beneath, and Between: Tracing the Thong

Keywords: Back That Azz Up, Back That Thang Up, brazilian bikini, Dru Hill, Fashion, feminism, Sisqo, thong song, thongs, trends, victoria's secret

Natasha Stagg investigates the historical, sociological, and cultural crevices of the much-maligned undergarment.

I can still remember being confused by the thong when seeing it in stores. Once, in Victoria’s Secret, as a teen, I asked a clerk how one should wear an example of the strand- of-pearls thong.

“You just, put it on,” she said.

There was something too real about the way those pearls would have to expand the crevices about which I was conditioned to try to forget.

The thong brings up anxiety. Like all studies of fashion, that of the thong is intrinsically connected to the history of humanity. But certain areas of study wish they weren’t wrapped up in the thong’s basic shape, it seems. Although it lies beneath the thinking behind so many historical moments, it is underrepresented academically. As goes its popularity, the thong has suffered peaks and valleys, but however argued-for it is, the small piece of fabric will always be argued over. The very form of the garment, which relies on oppositional tugging to gain its preferred shape, even seems to suggest this.

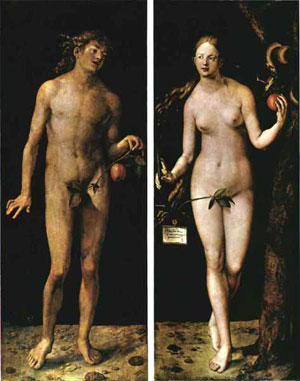

The origin of underwear is a foggy topic, and even further disputed is the origin of the thong. In the Western mind, Eve’s first bite into the forbidden fruit constructed the fig leaf, which logically must have been somehow tied to the wearer. In most cultures, a type of loincloth originated before a more complicated brief or bikini pattern, but this is still a shockingly under-researched topic. Anthropologically speaking, the loincloth and all of its forms are synced with the apparent barbarism viewed by European voyagers in nearly every continent they colonized. Slaves and servants in Europe and in Euro-colonized countries were forced into wearing loincloths—while their masters dressed in many starched and ruffled layers—to display subservience, even though the loincloth was originally a garment of function in hot climates and of practical crafting in locales where the buttocks were no more taboo a display than the arms or legs.

The origin of underwear is a foggy topic, and even further disputed is the origin of the thong. In the Western mind, Eve’s first bite into the forbidden fruit constructed the fig leaf, which logically must have been somehow tied to the wearer. In most cultures, a type of loincloth originated before a more complicated brief or bikini pattern, but this is still a shockingly under-researched topic. Anthropologically speaking, the loincloth and all of its forms are synced with the apparent barbarism viewed by European voyagers in nearly every continent they colonized. Slaves and servants in Europe and in Euro-colonized countries were forced into wearing loincloths—while their masters dressed in many starched and ruffled layers—to display subservience, even though the loincloth was originally a garment of function in hot climates and of practical crafting in locales where the buttocks were no more taboo a display than the arms or legs.

The Japanese thong-style fundoshi, for example, was originally the only style of underwear worn in Japan and later became the classic garment of powerful warriors—samurais and sumo wrestlers. It is still worn by average male citizens during traditional ceremonies, and while swimming, as outerwear. The fundoshi loincloth comes in a few forms, including a new female version, and is, according to the Tokyo Times for the past few years, making a comeback, being called “power underwear.”

Professor Otto Steinmayer says the reason behind a lack of research in the area of Eastern undergarments is the Westerner’s lack of understanding of the loincloth, due to personal history. In his essay, “The Loincloth of Borneo,” he refers to European men’s dress as “arctic” and inherited from the Roman style of trousers and shirt. “The only thing in Europe which resembles [the loincloth] is underpants, a garment that has a history of scarcely a thousand years and whose dignity and consequent esthetic value has been nil.

“Europeans have always considered the loincloth an immodest garment” because of what it leaves bare. Most cultures have at one point come up with a standardized shame concerning the nakedness of genitalia, but “it seems to be a peculiarly western trait to feel equal shame about the buttocks, probably from a fear of homosexuality, an anxiety which also seems to grow with civilization.”

The thong has come to represent more than primitivizing a culture’s misunderstood dress. It is brought up in the conversation of objectification, too. A thong bathing suit, like the ones Coco Austin, star of E!’s Ice Loves Coco, famously wears in her “Thong Thursdays” Twitter updates, has become representative of air-headed hyper-sexualization and material concerns.

The question of whether a feminist can wear a thong is, according to Jennifer Baumgardner and Amy Richards, “symbolic of young people’s relationship to feminism: meaning that the relationship is often personal, invisible, and uncomfortable.” In fact, Baumgardner and Richards call this question “The Number One Question about Feminism” in a similarly titled essay.

Asia Argento

The word “feminism” has undergone a transformation as interesting as the history of the undergarment. Its relationship to dress is undeniable, but the blurred lines between gender studies and fashion design sometimes make themselves clearer by drawing attention to the differing priorities on either side. Sex is fashion and fashion sex; gender is sex and sex gender. Still, fashion can try to ignore gender, and gender can discriminate against fashion. It’s okay for a feminist to wear a thong, but is it okay for a thong to be representative of feminism? Perhaps more importantly: Can a thong be representative of anti-feminism?

Fashionably, the thong changes its mood every few years and represents something new. The thong is rebellious: It sticks out, hides again, becomes functional, emerges as decoration, and stretches itself thin.

When I was eighteen, my first real boyfriend asked me if I wore thongs. No, I never had, I said nervously.

“Good. A thong is like a railroad track for bacteria to move back and forth between cultural centers.”

So, why do people wear thongs, besides tradition or rebellion? Maybe a more important question is why people wear underwear at all. But do we really need to start asking that again? Underwear is hardly functional. That a type of underwear is at any given time more stylish than another is never based on function. The most basic panties and bra do at least make sure nothing of a body is illegally displayed in case of clothing malfunction. But that we prefer boxers of briefs, low-cut versus high, etc., is based on whims of fashion. What we wear under our clothes, whether it is displayed while we are clothed or for the short period of time between when the clothes come off and the next step, becomes decorative if it is adhering to any trend—which it must, in order to have been made in the first place. Going without (a.k.a. “commando”) has come in and out of style as well, with stars like Britney Spears and Lindsay Lohan flashing their genitalia while getting out of cars.

A cheap thong looks to me like something that has washed onto a shore and dried out. It looks uncomfortable. But more expensive ones worn right are unforgettable, suggestive, and I would even say endearing. Conversations about thongs, in groups or women, range from the I-don’t-care-I-like-the-way-it-feels attitude to the I-have-to-wear-one-to-avoid-panty-lines complaint. But ever since its first rise to popularity in the twentieth century, the thong has been dragged through the mud. It is still considered uncouth (and is still discussed in many communities as an issue of legality) to wear thong bikinis at the beach. Thongs signify strip clubs, over-sexed teens and the lower class—Frederick’s of Hollywood stores and Hustler magazine online as compared to the more family-friendly Victoria’s Secret runway shows on network TV and the Playboy channel.

A cheap thong looks to me like something that has washed onto a shore and dried out. It looks uncomfortable. But more expensive ones worn right are unforgettable, suggestive, and I would even say endearing. Conversations about thongs, in groups or women, range from the I-don’t-care-I-like-the-way-it-feels attitude to the I-have-to-wear-one-to-avoid-panty-lines complaint. But ever since its first rise to popularity in the twentieth century, the thong has been dragged through the mud. It is still considered uncouth (and is still discussed in many communities as an issue of legality) to wear thong bikinis at the beach. Thongs signify strip clubs, over-sexed teens and the lower class—Frederick’s of Hollywood stores and Hustler magazine online as compared to the more family-friendly Victoria’s Secret runway shows on network TV and the Playboy channel.

The thong doesn’t need to fight for a better reputation, because it sells, and it is its hidden agenda that gives the style popularity. Even in junior sections of mall department stores, there are often as many thong options as non- (I am combining the categories of boy-cut and bikini but leaving out the now ubiquitous control-top panty). When one wears a thong, she or he can feel the secret throughout the day. The wearing of the thong can mean a multitude of deviant actions. It is strangely at once conservative and reactionary, for example, that so many feel the need to hide panty lines by creating the illusion of going underwear-less.

Even in the 1990s, a new wave of popularity and mass-acceptance was brought on by a linguistic adjustment in mainstream understanding. In 1992, MTV played Kyuss’s grungey “Thong Song,” which contained the lyrics, “My hair’s real long/no brains, all groin/no shoes, just thongs/I hate slow songs.” In 1999, this title was already dated enough to allow a new song with the same name to play on MTV and become a huge success. Kyuss’s understanding of the word was now laughable, while Sisqó’s was the agreed-upon definition. In his video, clearly, the focus is on a female’s ass. Comparing the two videos provides not only an illustration of the changing definition of the word “thong,” but of the changing expectations of music videos on MTV.

Kyuss’s video is simplistic and dimly lit, with band members slowly fading in and out of view. A narrative is built into Sisqó’s “Thong Song,” starting with a film-like intro that includes a subtitled location shot, a dialogue between the protagonist and his on-screen daughter, a comedic 1990s-typical zoom to a distraught facial expression, and an expositional monologue before the onset of music. The dancers of the video have their own narrative, which involves getting out of tour buses, playing on the beach, and then dancing on a black-lit floor. The differences between 1992’s and 1999’s videos are higher production value, higher attention to an average viewer’s attention span (a dramatic structure, made up of a protasis, epitasis and catastrophe), and sexual stimulation.

Sisqó’s and Dru Hill’s “Thong Song” was only regarded as a danceable summer joke, but its video was typical of not only the cheesy R&B seducers and the hair-metal womanizers of its time in terms of objectifying women. In fact, I remember hearing (and making) the complaint that for a song about thong underwear, the video was far too tame, with too many skinny dancers wearing boy-cut briefs. Censors must have pushed all of the actual thongs into the blurry background of the black-lit scene, and completely out of the beach takes.

1999 was also the year Juvenile’s “Back That Azz Up” came out on CD, and the radio-friendly version, “Back That Thang Up” came out on MTV (and, in my staticky memory, became the most requested video on network TV’s experimental all-request channel, The Box). This video’s devoted anti-high-fi look accepted the task of depicting the lower class at a block party. This approach spurned a generation of sexually explicit rap content dealing with women wearing Walmart brand outfits or cheap exotic dancewear to perform for music videos. The extreme slow motion of the ass-centric shots made it undeniable that these women were wearing either nothing or a thong under their thin denim and khaki shorts, thereby making this video far more sexual in nature than Sisqó’s beach party.

Three of the most notable after-effects of “Back That Thang Up” are Nelly’s 2003 remix “Tip Drill,” Ludacris’s 2007 single, “P-Poppin’,” and Sisqo’s 2000 follow-up to 1999’s “Thong Song.” In the video for this newer version of “Thong Song” (featuring Foxy Brown and exclusively created for the film Nutty Professor II: The Klumps), a notable change has occurred. Video girls in these shots parade in thongs and matching tops on an outdoor runway. The “Back That Thang Up” slow motion ass-take is in full effect here and the focus has changed from a glance at a group of partying girls to a long stare at each girl’s thong, one at a time. The video still has a narrative, but more attention is placed on texture: the clothing worn is beaded, scaled, and lacquered, shimmering slowly and dramatically for the viewer.

“Tip Drill”—the chorus of which is “It must be that ass, cuz it ain’t your face”— uses a similar style of cinematography. It was highly censored but hardly played on air even still because of its controversial lyrics and video content, which takes the theme of voyeuristic intrusion one step further. “Tip Drill” speaks of and shows women wearing thongs and taking them off, whereas “Thong Song” only asks a person to show the thong itself. “P-Poppin’”—the chorus of which is “Get down, pussy, pussy-poppin’ on a handstand,”—became “Booty Poppin’” for MTV. The video, which tells the story of a p-poppin’ contest a the notorious Magic City strip club got limited air time for obvious reasons. The TV-friendly video is so blurred, it becomes an advertisement for the original version. The video was one of many markers that spoke of a move to internet-interest as opposed to television. “P-Poppin’” is not available on YouTube, either, so the amount of plays it has gotten is hard to tell. The video responses—search: booty poppin, twerk, drop it low, etc.—however, speak loudly about the amount of influence this and similar videos have had on a generation.

Low-fi big productions speak of yet another stage of the thong’s existence in popular culture. The thong is a hidden object, squeezed between lobes. The realness of these videos could spare no sensitivity to subject—women here are stripping in a club, competing for a famous rapper’s attention at a pool party, or table dancing at a sweaty party. In the two newer videos I have mentioned, the women are wearing g-string thongs, clapping, topless much of the time, and bottomless for split seconds. Also, they are getting money thrown at them, and camera-light is shed on female faces infrequently. These videos were marginalized because they were so obviously celebratory of demeaning behavior, but also because their edits of reality were stark and uncomfortable.

The thong, too, is marginalized for obvious reasons: it hides itself, becomes obscure (unable to fight the battle of visibility because of the very position that defines it), and therefore misunderstood (semi-illegal). It denotes sexual deviance while it suggests an understanding of realness. The thong is closer by centimeters to the areas of arousal, which means it is that much closer to the truth behind our obsession with underwear. It is at once decorative and invisible, like the selling of sex itself. It asks what sex would feel like without censorship, what pornography would look like without an underground industry, and how far one can be pulled in any one direction.