Adjust Opacity

Keywords: 3D scan, Art, biometric, gayface, Jacolby Satterwhite, mask, phenomenology, reifying desire, Tracey Emin, Zach Blas

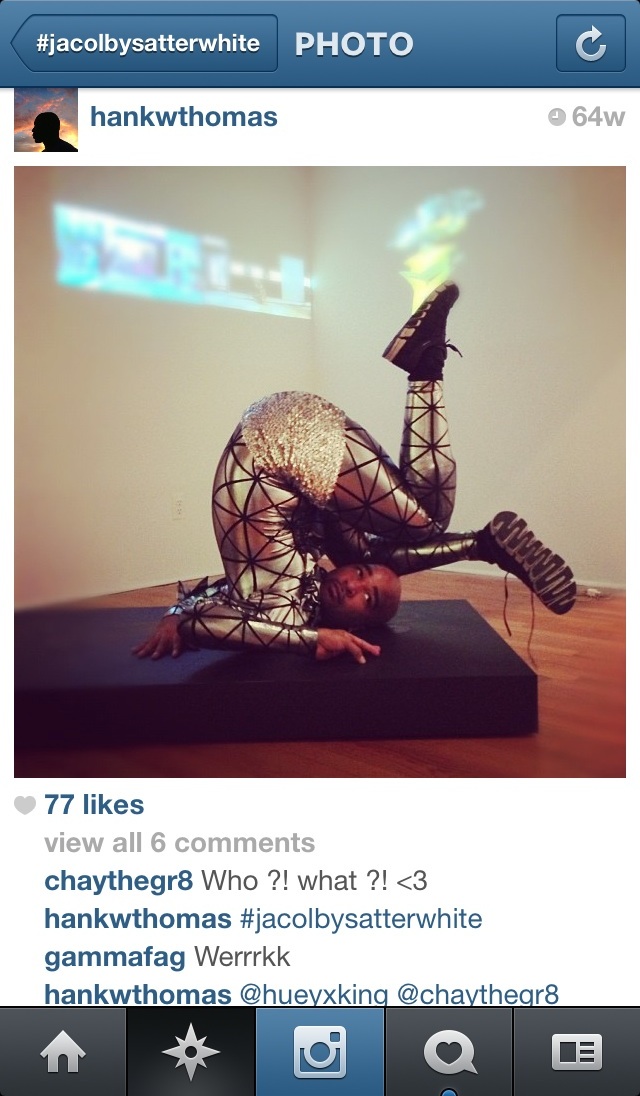

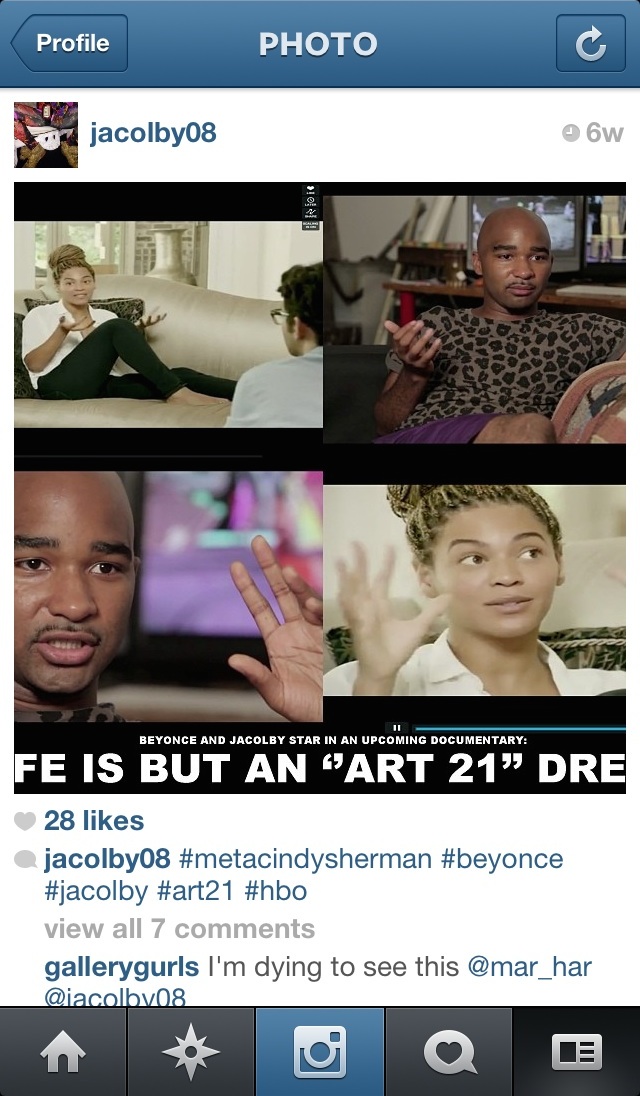

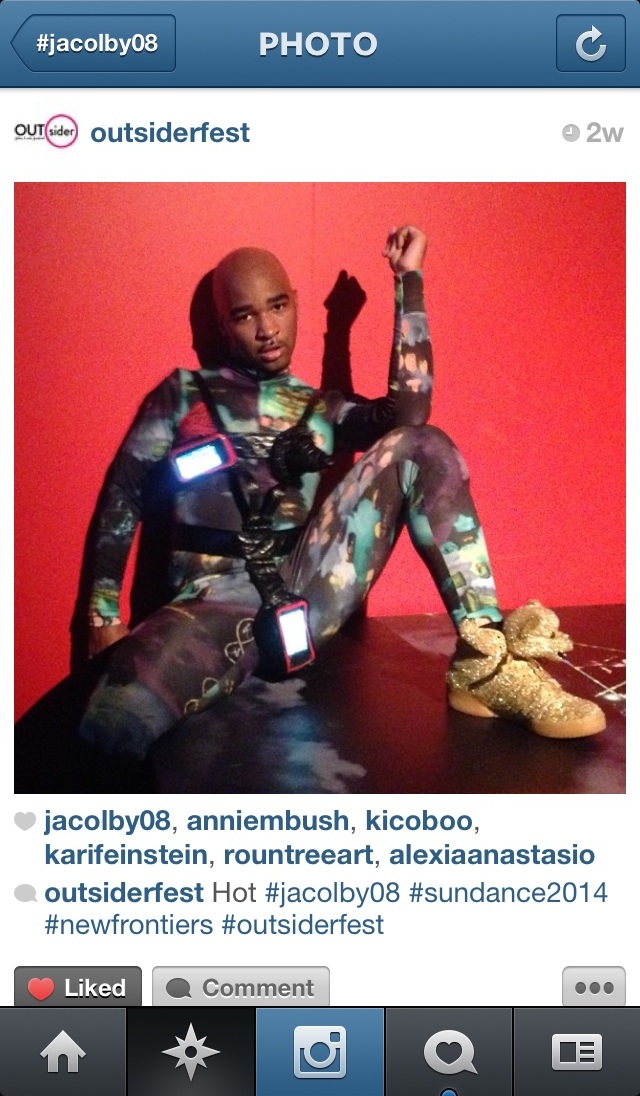

Jacolby Satterwhite’s work in video, performance, animation, and other mediums explores themes of memory, desire, ritual, and heroism. He received an Art Matters grant and his work is included in the 2014 Whitney Biennial. The two met at Eyebeam to talk about their shared interests.

Jacolby Satterwhite I recently wrote short entry about ratchet culture as the new uncanny for Flaunt magazine. It was a fun excuse for me to talk about mediatakeout.com, Rihanna and Miley Cyrus as case studies. It was about digital media and the use of Photoshop to perfect yourself and appear godly. Living in a time where everything is mediated causes a collective resistance against beauty. The new glamour is being porous and parading your errors.

Zach Blas I was just reading about Jennifer Lawrence on the cover of Flare, and there were images demonstrating how intensely she’d been photoshopped. People were angered by this because if you’re photoshopping Jennifer Lawrence, who is already so beautiful, beauty just becomes another unobtainable standard.

JS I know, it’s weird how some people still pursue a more false aesthetic even though the general public clearly prefers a degree of realism. I’m a big hypocrite here because in my work I generate the most extreme falseness imaginable. But I find that parallels the zeitgeist, because I have an almost Tracey Emin-ish, heart-on-my-sleeve honesty. I let it all hang out. I let my body of work build around public and private narratives.

ZB Could you say more about the false?

JS My worlds are false and yet they’re real because the touch is so there. There’s so much analog interaction with the media that I work with. Realism is inevitably there because I’m using Maya and After Effects to trace a drawing or a real performance in front of a green screen. There aren’t that many misleading graphic embellishments. There’s a tactile relationship between my movement, the 3D animation, family photographs, outsourced performers, online media, and my mother’s drawings. There are the relationships with the people I invite to my studio to interact with me, whether I’m having sex with a porn star, or I’m just doing yoga with someone on a mat in front of a green screen. All of these things are real, but I mediate them with technology. It’s just like making a painting.

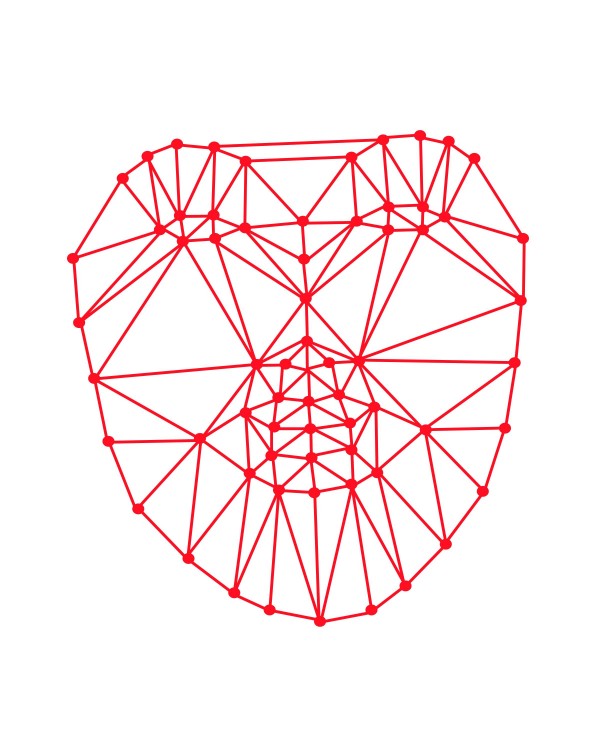

ZB The way you talk about analog makes me think about my own relationship to it. I’ve been working on this mask project called Facial Weaponization Suite for a few years. I organize workshops with a group of people and gather 3D scans of everyone’s face to produce a mask from a collective biometric aggregate. I could just scan 20 people’s faces and use an algorithm to bring it all together. But I’m never satisfied with that result, so I do it by hand. I put a bunch of scans in a 3D modeling program, and then I play with layering, to affect how everything emerges and blends, to produce a kind of excess is produced that is more than the sum of several peoples’ faces.

JS So you’re pursuing abstraction through representation, in a sense.

ZB Yeah, I like to think about what it means to collectivize the face in data in connection with social movements and masked protest. Pussy Riot, the Zapatistas, Black Blocs, and Anonymous all use masks for collective consistency. That’s what’s amazing about looking at the Pussy Riot Solidarity protests, for example, because they’re all wearing a certain style of mask, and it gives them aesthetic consistency as a group. So I decided to take this idea very literally: What would it mean to create a mask that a collective, or group of people, could wear, based on the aggregated data of their faces? The abstract result is important because I never wanted to average the data and get a “normal” face. The mask, as a collectivizing process, produces excess, which moves to a weird, amorphous place.

JS Oh, that’s interesting.

ZB The face has always been a site for articulating human ethics and responsibility, but the inhuman quality of these masks greatly affects peoples’ behavior and engagement. But the mask isn’t just hiding a face, it’s styling the body. There’s something positively transforming about the mask. It can make you invisible to surveillance, but it also transforms you through style.

JS I wore masks in the first three years of performing, but they were just simple stocking masks like the kind that robbers wear, sewn to a catsuit. I didn’t want the body politics of being black to enter the work, because once you’re black as an artist you can’t work in certain genres without it evoking a postmodern association with a certain history, or an ironic, tongue-in-cheek relationship to identity and movement. And I thought that had nothing to do with me. I started wearing masks because I wanted people to think about a strange post-race and post-gender body operating in the world. With the mask I felt like the anonymity was so intense. My presence was neutralized. By not having a face, I became a prop in the space. So I think your work is very important.

ZB What I like about the abstract mask is that it forces you to have a relationship with a face where you can’t identify the difference that you’re looking at. A kind of unassigned alterity is looking back at you. The first mask I made in the Facial Weaponization Suite was Fag Face Mask (2012). It was inspired by a series of scientific “gay face” studies that have been repeated at various universities since 2008. I found them incredibly problematic because I’d grown up with gay face as a form of harassment. People would tell me I had fag face when I was a kid.

JS Oh, that’s messed up.

ZB And now these studies supposedly confirm that you can successfully identify whether someone is gay or straight by looking at their face for 50 milliseconds, which is almost at the subliminal threshold.

JS That’s a fucking lie. I wouldn’t even say that as a joke. I do think you can tell if someone’s really aggressive in bed by looking at their face…Though some people surprise you.

ZB Well, there’s a difference between using these words in various subcultures and making scientific claims to an objective truth. So anyway, that’s why I wanted to make the Fag Face Mask look incredibly alien, to present a queerness that refuses to be understood through such a scientific lens.

JS That’s how I approach objects and animism and phenomenology. I read Queer Phenomenology by Sara Ahmed which talks about how different bodies interact with different objects. It spends a significant amount of time distinguishing a table’s relationship with a librarian, or a writer, or a gay person, or a chef… Everyone and everything has a certain role. I use objects designed by my mom, because it’s an inventory of things that I can repurpose for specific bodies. My virtual performance arenas are queer places where the viewer is challenged to adapt to the spirit of my ideas. That’s how I act as a performer. I disrupt logic. I force the viewer to assimilate to my standards. Psychologically that’s a way of pushing back to reductive recognition, things like gayface.

ZB That’s an interesting point. I’m thinking about your Country Ball (1989-2012), which updated a home video of your family’s Mother’s Day cookout by cutting the footage into a computer-generated landscape of 3D models of your mother’s drawings. When you show that video how important is it that your audience knows about that background?

JS Gallery and museum didactics usually reveal it. But it doesn’t matter if the viewer gets it or not. I just need conceptual platforms to get me going. I was really excited by the idea of appropriating a banal camcorder video from 1989. I recently showed the camcorder footage alongside 3D animation at The Bindery Projects in Saint Paul, Minnesota, and at Momenta Art in Brooklyn. It’s more effective that way.

ZB I showed the video to some friends last night, and I wanted to see how they responded without knowing the backstory. I had first seen it when we were at Rutgers together for the Trans Technology exhibition and symposium in 2012. During that viewing, I felt like I was intuitively picking up on references to the past and memory.

JS I’m always working with several systems. When I had a residency at Recess Gallery in SoHo, I built an archive of movement from 270 people. Now I have a codex of body movements in relation to abstract objects, and my abstraction is getting denser and crystallizing, which allows me more freedom in putting it together. When viewers consume the work, they project all these things on me, but I have a very specific narrative and a goal. Nevertheless I think the work generates a spirit on its own, beyond what my intentions were originally.

ZB You use the phrase “reifying desire” as a title for a series of videos. Is that a narrative for you?

JS Narrative gets stitched together. I am making Reifying Desire 6, and remaking Reifying Desire 1 at the moment. So you’ll see when I finish it! Part three has the most linear plotline. Part five—I’ll be honest—I had a solo show, so I just put it together as quickly as possible. It was supposed to have a certain development, but I didn’t succeed because of the deadline. Now I’m remaking parts one and six to make four and it’s like a weird creative puzzle that I’m doing publicly. And people are seeing it as it evolves.

ZB It’s fun when that happens. That’s what’s been happening to me, too. My goal is to produce five masks. But it’s really labor-intensive, because the workshops happen in different cities with different groups of people, so I have to find people and spaces to work with, build relationships, and figure out how to make the masks locally, in the sense of site specificity. In December, I co-led a seminar at CUNY, where I partnered with Simone Brown, a professor at UT Austin in African and African Diaspora Studies and an amazing scholar of race, biometrics, and surveillance. Her work connects contemporary surveillance to histories of slavery. She reads the literal branding of slave bodies as an early analog marker that commodified those bodies and connects this to contemporary biometric tracking. She gave a talk, then the two of us did a workshop together afterwards. It wasn’t an art audience, but more of a scholarly one. I spoke about my mask work, and another project that I’m working on now, a critical dystopic component to the mask work called Face Cages (2013-present) I take biometric diagrams generated by analyzing faces and fabricated them as metal objects. When people look at biometric diagrams on a computer, they usually say, “Ooh, this is so fun!” There are bright colorful lines, they move and follow your face… But many people do not think about how these technologies are developed by private security companies to police and criminalize populations all over the world. The resulting object looks like a torture device, which is important because I want to connect the face cages to issues of imprisonment and criminalization. Metal can evoke handcuffs or prison bars.

JS Yeah, I think that’s great. I think you’ve found where portraiture should go in this era. It makes me think of the Mona Lisa and the mysteries of her face. Some historians used facial recognition software to argue argued that the Mona Lisa was Leonardo da Vinci in drag.

ZB That’s so bizarre. Today, we have a procession of official portraiture: the passport, the driver’s license, the mug shot. Now there’s the biometric diagram. It’s an abstract portraiture directly connected to political violence and dehumanization. I’m very taken by these antimonies of abstraction, between the biometric diagram, on the one hand, and the excessive abstraction of the masks I make, on the other.

JS Many people feel the concept of identity puts them in a cage, whether it’s a racial identity or a standard of beauty. People are very sensitive in a way that I find surprising. I mean, I have certain issues regarding body image. But my studio and performance practice have erased most of them. Performance really allowed me to love my body more than I did before. I had a lot of surgeries as a kid. My body was not shaped normally, due to several bone grafts and scars, so I don’t have a “gay body”…

ZB I have no idea of what a “gay body” should look like.

JS I know! But things changed once I sold my soul to my alter ego.

ZB Is that how you think about yourself when you’re performing? You transform?

JS I do. I don’t even remember the people I meet. People tell me we met when I was performing and I say, “No, we didn’t.” I don’t know if I’m bipolar or something but as a performer I’m capable of behaving in ways that I could never outside of the performance. But lately they’re blending. I forget about my body and my face. Once I cut that off, I’m a shy ass nerdy stupid little boy. I’m more aware of the cage of my face and my bones and my flesh. As a performer I transcend flesh. I’m more of a digital figure. There’s a formalist property to my social sculpture. I’m not being pretentious, this is really what happens. My body as a performer comes from 3D animated worlds. The context for my body isn’t planet Earth, it’s virtual reality. When I psychologically trick myself to have no reference to the real, I am free. That’s why I brought all this up. As a performer, I come from planet Jacolby; But as a studio artist, a.k.a regular Jacolby, I come from planet Earth, and I live under the consequences of the past 400 years of black American history. I live under the consequences of real human politics. But in the institution of art and my artwork I dissociate myself from earthly matters that make you have to dissect the body.

ZB Yeah, that seems like a really important aspect of your work. I like that there’s an escape factor there.

JS I screened Dancer in the Dark at the Independent Film Center’s Queer/Art/Film series last fall, and people were like, “What does that have to do with his work?” For one thing, I like movies where the character experiences trauma and it’s too much for her so she goes into a fantasy land and start dancing and singing. And that’s Dancer in the Dark. She’s an immigrant. She couldn’t assimilate to American culture. She got in trouble and she was going blind. It’s similar to Lee Daniel’s movie Precious—there’s a scene where the heroine is getting raped and in order to cope she drifts into a dream state where she’s a diva on the red carpet. There is something about that friction I find very important.

ZB You create a character who’s not from Earth because it gives you a free persona that’s not weighed down by all the forms of political oppression or the burden of history that you have to carry as a human being from this planet. I think that with the masks I want to create a transformative collective presence where we still think of ourselves as humans on planet Earth but we’re creating an object that allows us to transform together into something that looks absolutely not human.

JS What you’re doing reminds me of early queer theory, when its purpose was break everything down to a science so people could lose subjectivity. It was forcing objectivity through the most abstract things about life. What you’re doing is moving all the sex shit, black shit and Asian shit out the way, getting straight to the bones and eyes and nose, the source of all problems of misunderstanding that affect the way we see each other’s faces and feel fear. I mean, put two cats in a room and if they don’t know each other they get violent—“HISSS.” It’s natural. So it’s great that you’re teaching people about abstraction.

ZB Yeah, it’s almost a way of training people to perceive others as an abstraction, a material presence without identification or categories. I like to talk about this using the term opacity. Lately I’ve been really influenced by Édouard Glissant, the Caribbean philosopher. He has such powerful ways of talking about opacity within a post-colonial framework, advocating a struggle for the universal right to opacity.

JS I thought transparency would be better.

ZB In the history of various minoritarian struggles, whether it’s black, queer, or the undocumented, there’s usually a common rhetoric about the need for visibility, which means transparency to the state, which will in turn hopefully result in equality established through governance. But he flips that around and says opacity is complete acceptance of the indefinable difference of things in the world. Forcing an interpretive framework on to another person is violence. For Glissant, transparency requires an assumed common ground before anyone can understand what transparency means. As he puts it, a Western idea of transparency gets projected on the world as a project of imperial domination.

JS But aren’t you trying to develop transparency?

ZB I think that biometrics and facial recognition force a transparency that is reductive and harmful. The masks make the face opaque to facial recognition technologies while crafting other ways of becoming visible within a group of people—an autonomous visibility that does not cohere to surveillance technologies or the state. A couple years ago a queer theory book came out called Opacity and the Closet by Nicholas de Villiers, which looked at Andy Warhol, Michel Foucault, and Roland Barthes. He said that these three queer figures annihilate the framework of understanding homosexuality as something that is either in or out of the closet. It’s a limited way of imagining the potential of queer opacity, but I thought it was a powerful concept to expand and develop further—and to connect with Glissant’s opacity. For de Villiers, queer opacity is purely tactical, while for Glissant it’s relational, ethical, and ontological.

JS That’s fascinating. I feel like I live in that zone of queer opacity.

ZB So is queer important in your work?

JS Not like gay queer. But feel like abstraction is important and I think queer and abstraction are synonymous. I just say queer because it’s a more spatial term. My digital work, performance, and sculpture is a resistance to traditional fine art practices such as painting. In my opinion, queer means finding utopian free autonomous space for being a brave individual.

ZB Yeah, I really value thinking of queerness beyond some type of sexual orientation. At its best, queerness is a practice of subverting normalization and taking great pleasure in doing so. I’m interested in biometrics because it standardizes identity at a global, technological scale. I’m interested in what it means to think about queerness as a subversive tactic at that level. I like dealing with this in art because art insists on some unquantifiability.

JS But wasn’t seeing from all perspectives the purpose of modernism? When Courbet painted A Burial at Ornans, it was shocking that he would give regular people who were unrecognizable a big canvas. It polarized the art world. The same goes for Picasso and Cubism. Everyone was pursuing their own personal truth. Picasso was trying to paint a vagina, a dick, eyes, and tears all at the same time from different perspectives. It’s crazy but I think this is the consequence of modernism, a journey from Cubism to biometrics. Evidence of the body has been important for the twentieth century.

ZB You talk about bringing your body into these 3D worlds and creating his other persona, so how important is technology for you in conceptualizing your work?

JS It allows me to expand on the formalist concerns I had as a painter. I was a formalist with quasi-pretentious, Bauhaus-y obsessions with texture, planes and lines, shapes and possibilities. But I can make them move now. I’m a twenty-first century kid with a 3D animation program at my disposal. My body allows me to do way more things. It lends itself to more dynamic drawing principles. When I trace my movements digitally I make very interesting things happen with line, composition, light, and shadow. In a time-based medium these things escalate in another dimension. I trace my body in a certain way when I import it from After Effects. I have more technique and more touch.

ZB Is working with 3D modeling crucial to your practice?

JS 3D modeling fulfills my addiction for image making. But modeling also is a very tactile digital craft. I started playing with 3D models of my mom’s drawings and realized that it was a toy box full of probability and chance. So it’s all been trial and error, pursuing a language that I’ve been desiring since I was a kid. It comes from being a gamer—being lost in infinite 3D arenas like the ones seen in Lara Croft: Tomb Raider, The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time, Metal Gear Solid, or Resident Evil is what shaped my visual lexicon.

ZB It’s interesting to hear you talk about 3D modeling because it was in some of my earlier work, in a tangential way. What I like about it now is that it allows me to produce objects that have emerged from a computational world. I’m compelled by this process of materialization, when you are forced to engage with the 3D model as a physical object. So many tensions, differences, slippages emerge. Are you interested in 3D printing or fabricating objects like this?

JS I am, but my objects are so sloppily made they have these open triads. So I have to do a lot of cleaning in order to print them.

ZB But perhaps that’s one of the beautiful things about keeping it within the digital world. Of course, it’s still material but you have a different kind of agency. Fabricating, 3D printing, CNC milling—all these methods enforce their own standards, regulations, requirements, that is, precision. But I suppose it’s the trade-off one must make in order to leave the frame of the computer screen.