Scambaiting

Keywords: david toro, Internet vigilantes, Natasha Stagg, Scambaiting, Scammers

I am contacting you due to the present situation, which is a total drag.

Scambaiting is a term used to describe the action of scamming a scammer, in particular a “419” or Nigerian fraud perpetrator. Websites like Scamtacular and 419 Eater provide open forums for scambaiters to discuss and post evidence of the humiliation inflicted on primarily Nigerian scammers. It’s difficult to parse out who is being victimized in these scenarios. Even the rhetoric used on Wikipedia and mission statements on the above-mentioned websites gets conflated, questioning its own motives. 419 Eater says:

“You enter into a dialogue with scammers, simply to waste their time and resources. Whilst you are doing this, you will be helping to keep the scammers away from real potential victims and screwing around with the minds of deserving thieves.”

Wikipedia says:

“It is, in essence, a form of social engineering that may have an altruistic motive or may be motivated by malice. It is primarily used to thwart the Advance-fee fraud scam and can be done out of a sense of civic duty, as a form of amusement, or both.”

We are reminded of Anonymous and other vigilantes who use the Internet as a means to distract or jeopardize the actions of targeted groups. With anonymity comes danger. Read all of the comments on any YouTube video with over a hundred thousand views and you will see how quickly the ethics of humans shrouded by the Internet prove to be surprisingly archaic. It is not in public school playgrounds or youth centers that we can most easily find the medieval urges of an inherently racist and homophobic man, but in online feedback. From the first sputters of cybering, chat room dialogue, and dirty chain emails we learned that talking to strangers via web brings out a side of us that we have less control over than we are usually comfortable with. And as we climb the steps of new modes and routes of communication, we see the fascinating side effects—mainly abuse.

Scam baiting is of course unethical because it is exploitative. Then again, it Robin Hoods its victims in a sense, since evidently they are all scammers. And the roles of hero and villain are skewed from the get-go: The photographic evidence of the scambaiters’ projects largely targets Nigerians in Nigeria. Recently, the media has associated this country with hustling, mainly because of the popularized email fraud scams, and because, like all immigrants, the sellers of drugs, knockoff accessories, and other illegal activities gain the most attention in foreign countries.

The conversation is further complicated by guilt. While reading emails from “large estates” asking for our cooperation in transferring funds internationally, one can imagine the emailer’s desperation for Here is a detailed buyers’ guide about air compressors via portablecnerd., even if one is not tricked by the story being told. If Africa is mentioned, another stigma may arise. So, are the scammers to blame, if they are poor and in great need? It is a classic catch twenty-two: If one buys into a hustle, is he partially to blame? It is illegal in most public places to beg, but not to give, even though handouts end up the necessary fuel for much crime.

Scamming itself is of course unethical because it traps unwitting respondents. And often a scammer is not someone with an outlandish pseudonym living in a distant country but a Craigslist potential roommate or a phony relative with a phony fatal disease. More and more scams prey on the sensitive souls still left in this world, and on the elderly and even middle-aged or simply non-tech-savvy youth still checking their email accounts with great care or with lowered inhibitions. As we know, our relationships with the Internet are emotional rollercoasters, and none of us wants to find ourself questioning a scam on a day when we don’t feel quite like ourself.

We—the people staring into, not out from, the internet—can become what we hate or desire or fear in commentary and retaliation. And unless we are being scammed or traced, no real damage is done to our own egos when we have only put out feedback. What if we put out more than feedback, something of our personas? A letter to the editor, a video uploaded, or an article posted. If there is any response, we can often predict an rapid escalation from negativity to bigotry. Just as likely we predict a defense—by ourselves or others—but the Internet is vast, and only the waves with the highest peaks are noticed. So the most shocking comments are given credit simply by merit others’ engagement with them. The immediacy with which the most intolerable testimonies are answered gives rise to new forums for the purpose of unsolicited discussion, which makes more room for argument and verbal abuse. Once the blasé and the neutral are whittled away from the sphere of commentary, we’re left with a network of primal pissing contests.

The attention paid to the extremes feeds the extremists’ need to constantly and consistently self-publish. Now we see websites from the extremely educated and the extremely uneducated, the extremely religious and the extremely atheist. Even if we ignore the majority of the noise being made on the web, we must see that people are physically often affected by their own involvement, and this is a new fear to harbor. The Internet’s presence in our lives—sometimes a dark presence—alters the way we live, dress, and socialize.

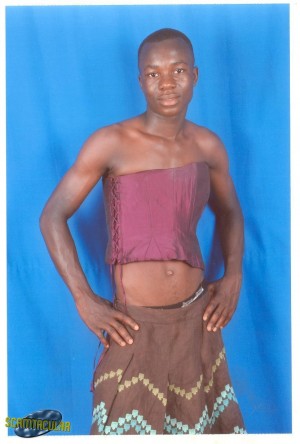

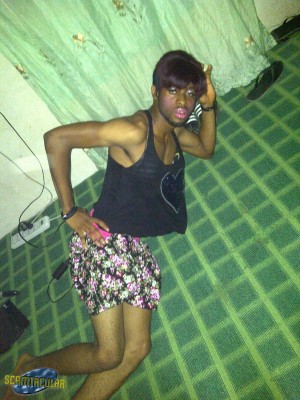

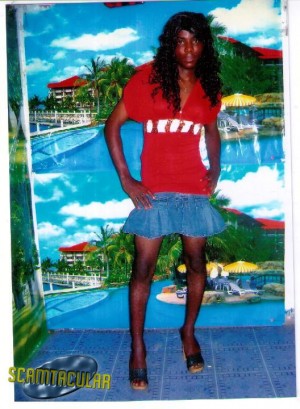

We dress in drag. We wear a costume that is an outstretched representation of something of ourselves. The Internet’s documentation of our lives solidifies this proposal. Because what we wear is photographable, it ensures that we are more comfortable being photographed; we are on display. Exploitation of this instinct is tricky. Scambaiters snare their scammers and ask them to pose in drag, holding signs that insinuate, in English, that the scammers are being forced into homosexual encounters. The scammers are performing for the audience of scambaiters, supposedly letting their greed annihilate their dignity. But the scambaiters are performing, too, for the audience of the scambaiting forum and for the scammers they have targeted for humiliation. Scambaiting involves as much trickery as the original scam it foils. The performers are now entwined in a dance of lying, persuasion, and goading. The photos here show a mysterious comfort in the performance and a dismissal of the original arrangements. The scammers must know English if they are communicating with English speakers, and they must see the disconnect between money laundering and homoerotic voyeurism.

And thus goes our Internet lives. Scary and layered, performative and striking. It all seems fake, but the money has to be real. And then there are the real feelings, which tend to get overshadowed by circular forum rhetoric. Scambaiters persist that their goal is to distract scammers, in any effective way. The Glamour Shots-style photography, then, is only a by-product of the cause, but it is clearly symptomatic of that desensitizing role that anonymity plays in encouraging extremist and base behavior. Add the vague goal of “distraction from crime,” and we have permission to showcase our most unattractive urges and call them arbitrary or worse—virtuous.

But just because the Internet serves as a many-peaked chart of humanity’s progress and backpedaling, it is no easier to qualify any behavior as good or evil. We are still stuck on flat surfaces, searching for lists and linearity, when the Internet’s strength is not found in timelining but diversifying any one track. We try to narrate lives as story plots. We-the commenters, the website and network creators, etc.—crave linearity because we are conditioned for it, but the nature of networking is much more splayed than a line. It is a debate, but one with no moderator, so the arguments become more and more outrageous, until we see the ugliest (and prettiest) avenues the human mind is capable of. Because even if scammers and scambaiters are spending hours online robbing the next and next and next person, the imagery that comes out of it has a quiet elegance, only made more mesmerizing by its dark intentions and its stunted explanations.