A Brief and Subjective History of Eco-Terrorism

Keywords: cabin, disaster issue, EcoTerrorism, god, Industrial Society, Isaac J Lock, Meekong River, Ted Kaczynski

The environmentalist struggle, from Noah, to Unabomber, to the Earth Liberation Front.

A Brief and Subjective History of

Eco-Terrorism

Noah thought that he was the only man alive who knew about rain. He thought he knew about it because God told him. Living, as he did, in a world where the dominant form of communication was talking to people in his immediate vicinity, he existed in a state of more or less complete unawareness of the rest of the world. He couldn’t imagine, for example, that the people of Mawsynram, in India’s Khasi Hills, would learn to live with nearly 12 metres of annual rainfall, or that the people living around the Meekong River would learn to thrive on the variety of rainfall that it’s drastic, often fatal, seasonal swelling and shrinking brought. He didn’t know it was likely that, elsewhere in the world, groups of people had developed strategies of migration, innovation and co-operation to survive, en-mass, extreme changes in the weather. So, when he realized it was going to rain a lot where he lived, he saved his family and some animals and left what he believed to be the rest of humankind to drown. Being on a direct line to God, he didn’t share his skills or his space on his ark. Instead, he assumed that it was up to him to start again and re-father the entire species. He was the original environmentalist-who-would-be-king.

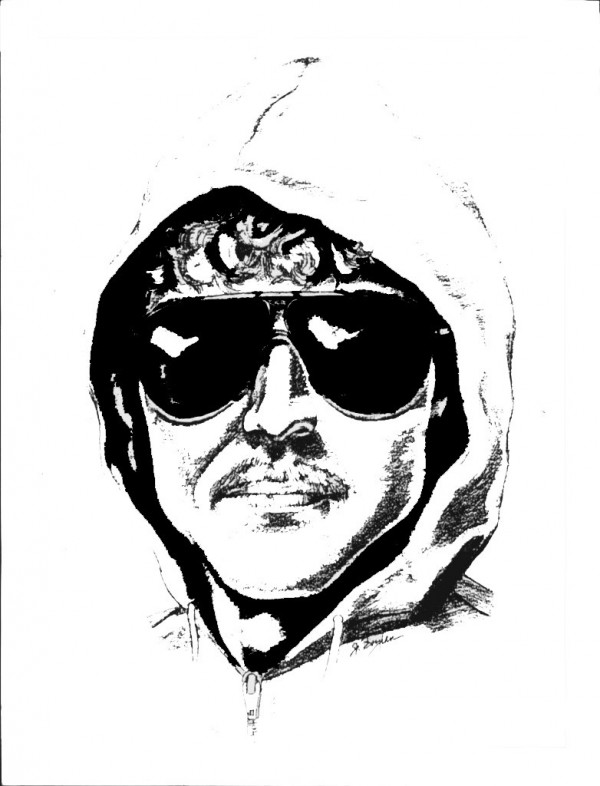

In 1979, Ted Kaczynski, a.k.a the Unabomber, tried to blow up an airliner using a bomb he had made himself (with, among other things, bits of wood and branch he had foraged). By this point in history, people who were interested – as he was – in shepherding humanity away from environmental ruin had, for the most part, given up on attributing their thoughts and impulses to the voice of God. Kaczynski didn’t believe his knowledge to be God-given like Noah did, but like Noah, he thought himself to have a privileged understanding of some occulted environmental information that he alone could understand and act on to save humankind.

While he did have a bunch of mathematical knowledge that pretty much only he understood (when he was studying a PhD in geometric function theory he came out with a thesis that a professor on his committee described as being so complex that it was understandable by only 10 or 12 other people in the country), his opinions on the environment weren’t that different from those of various other environmental groups that were active at the same time as he was. Even in the 70s the environmentalists message was, ‘Seriously, this might be way more fucked than you think!’ He was just really, really disconnected.

Kaczynski was a terrorist in the pre-21st century sense of the word. He was an eco-terrorist before eco-terrorism was a concept in the public imagination, and at a time before the attacks of September 11 ushered in a governmental redefining of the term. Unlike the operatives of the Earth Liberation Front – who were tried and convicted for crimes in the mid-2000s, and who’s interest was in causing property damage and economic sabotage but avoiding harm to people at all costs – his interest was in blowing people’s hands off and, when possible, killing them.

Secluded in a cabin he had set up for himself outside of Lincoln, Montana, Kaczynski spent almost a couple of decades, starting in 1978, setting bombs and sending them out to people he perceived as worthy targets in his struggle against environmental destruction and technological advancement. He targeted computer scientists, geneticists, and PR executives who worked with environmentally damaging companies. In 1995, he promised to stop on the condition that the New York Times and the Washington Post ran his essay ‘Industrial Society and its Future‘ in full. In it, he said that ‘the industrial revolution and its consequences have been a disaster for the human race’, and outlined in-depth criticisms of more or less everyone else that might have come somewhere near to agreeing with him – all leftist groups, all scientists. Some of his ideas were bordering on sound, and worthy of discussion at least. Yet in his rejection of anyone with even the slightest difference of opinion to his own, and his rejection of developments in technology that could unite and integrate different ideas and strategies for survival, he outed himself as the ultimate factional activist. He was in a faction of one. He called for a revolution following a very specific set of guidelines, set out by him. That is to say, he single handedly tried to re-configure the way the entire species interacts with the planet. He came as close to attempting to become the new father of humanity as a person with an awareness of our species’ breadth and scale can come.

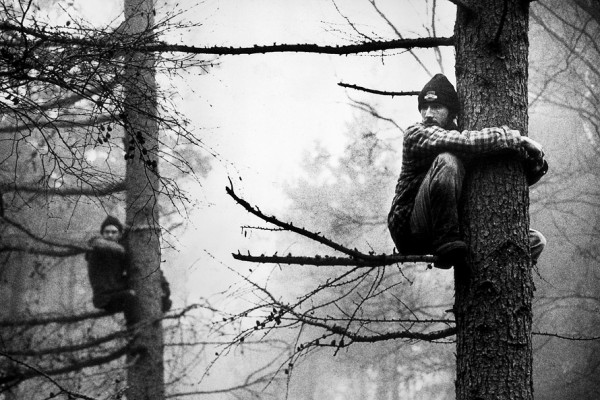

By the time Kaczynski got his essay published, a widespread environmental and anti-capitalist movement, entirely incidental to him, was swelling. In Newbury, in the North Wessex Downs of the UK, for example, thousands of people were coming together to try and protect a significant area of forest from being turned into a bypass road. People lived in tree camps and stood in the way of bulldozers and tractors, and became a national cause célèbre. Meanwhile, around Oregon and Northern California, thousands more took to old growth forests to slow the progress of industrial logging. A mass environmental resistance movement was forming – more urgent, connected, and incorporated than any movement like it before. (A 1996 news sheet compiled by the activists at Newbury for example describes financial sector executives, who had formed a group called ‘Business Against the Bypass’, turning up to protests in their Jaguars). On both sides of the atlantic, attempts to quell the protests served to open up mainstream discussions about the legitimacy of police and government force. As the image currency of the internet was beginning to gain pace, various images brought the movement mainstream sympathy and support: activists being dragged from trees, or crying heartbroken as they were felled, and videos of charming, peaceful, singing hippies so dedicated to their cause that they continued their sit-ins even as police swabbed pepper spray directly onto their eyes, .

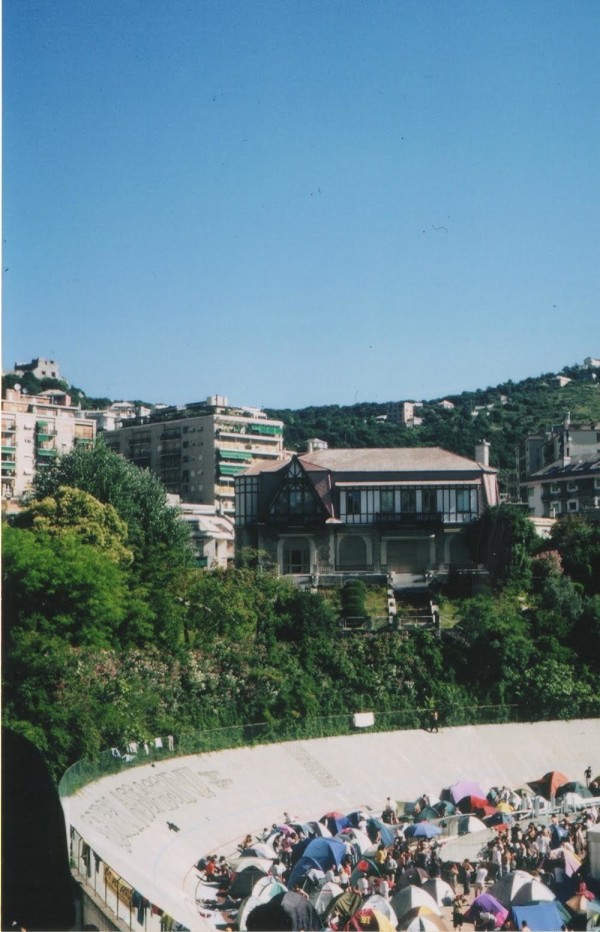

Meanwhile, in the major cities of Europe and the US, mass international protests were staged to intervene in global conferences of the world bank, the G8 and the WMF, and demand new solutions: the biggest international protests of their kind in recorded history. The rallying slogan of an international day of protest in 1999 was ‘Our Resistance is as Transnational as Capital’. For the first time, the radical shifts in communication technology that were taking place were being used to create an incorporated, co-ordinated move towards an environmental and economic alternative. While a huge range of tactics, opinions, and factions were invoked, the message at the aesthetic level – arguably the level most important for communicating to those not involved – was that these events were massive. A significant mass of people were considering the possibility of something other than a continuation of a system that was leading the world into a state of emergency.

When the aesthetic of resistance became aggressive – as of course it did, on account of the fact that images of a Starbucks having its window smashed in are inherently more attention grabbing than images of ordinary people holding placards – the result wasn’t alienating. Instead, the idea of mass economic sabotage began to edge onto the borders of mainstream discussion. The accompanying images of government response – police firing tear gas and water cannons in Seattle and Washington, the Carabinieri shooting a man in the head and running him over in Genoa – served, in the image battle, to legitimize the grievances of the protestors. These events – the protests in the forests and cities – where people staged disobediences and broke laws they believed needed to be broken, were open, massive, and public. They created a dialogue that anyone could partake in – even when groups had entirely opposed ways of operating. By participating in the same events, and contributing to the same spectacle, they were putting aside minor, or even major differences to work towards something else. An approach to changing things which is essentially the opposite of terrorism, which involves as many people as possible. It suggests a least a possibility of co-operation and innovation.

And then there were the ‘eco-terrorists’. In 2005, John Lewis, then the FBI’s counter-terrorism deputy-assistant-director announced that ‘The No. 1 domestic terrorism threat is the eco-terrorism, animal-rights movement’. In describing what he meant by terrorism in this case he said ‘Extremists have used arson, bombings, theft, animal releases, vandalism and office takeovers to achieve their goals’. This was four years after 9/11, after pre-2001 terrorism – the kind that kills people – had completely changed the landscape of discontents in America and Europe overnight. It was also several years into a widespread disintegration of the mass environmental movement.

The actions Lewis was talking about, attributed to the Earth Liberation Front, were arsons and vandalisms that had happened at ski lodges, lumber mills, wild horse corrals, meat packing plants and SUV lots. Arsons by people frustrated by the slow pace of change caused by public actions. At the end of 2005 and the start of 2006, 13 of the environmental activists Lewis was describing were arrested and convicted on terror charges as part of the FBI’s ‘Operation Backfire’. One of them killed himself in police custody, many of the others faced life without parole until they took plea deals and served sentences of up to eight years in prison, with ‘terrorism enhancements’ on their sentences, which meant they were held in special Communication Management Units – purpose built prisons-within-prisons that severely limit any outside communication.

In his 2011 film ‘If a Tree Falls‘, Marshall Curry looks in much greater depth at the implications of calling the people prosecuted in Backfire as terrorists and speaks to several of them about their motivations. ‘They [Superior Lumber, the target of an arson],’ says Daniel McGowan, an activist sentenced to eight years in a CMU, in Curry’s film, ‘were logging old growth, they were logging some pretty inaccessible areas. Sometimes when you see people destroying things you love you just want to destroy those things [that are destroying them].’ Chelsea Dawn Gerlach, one of the other activists sentenced has elsewhere described ‘a deep sense of despair and anger at the deteriorating state of the global environment,’ as her driving force.

These people emerge not as murderous psychopaths, like Noah and Kaczynski, but as people who had come to the conclusion that it was down to them and them alone – not an incorporated movement – to save the planet. They acted as they did under the belief that their despair was more urgent, that the rest of the world was not looking, that, like Noah and Kaczynski, they were seeing something that no one else was. And on a small, immediate scale they might have been temporarily effective – burning down a lumber mill certainly means that, for a time that mill will be out of action, and there will be a brief respite in logging in that area. They’re actions that probably feel immediate and seductive to those doing them: the thing is on fire right in front of you. It’s fast and splashy. But on a larger scale, these isolated actions worked against empathy, against co-operation, against a solution that anyone else could be involved in. They created an image for the movement that was suddenly secretive and elitist; one that most people couldn’t feel a part of any more. They were private actions that did not contribute to finding ways for the species as a whole to survive. ‘This is too much […] This is futile,’ McGowan says eventually, in Curry’s film. ‘There’ve got to be better ways of addressing what is going on in the world than just burning things down.’

These actions coincided with the disintegration of the wider environmental movement. Regardless of whether or not they count as real terrorism, they created a public spectacle that was terrifying and alienating, in a culture where even the mention of terror or violence was automatically associated to the opposite of freedom. ‘I think people were self righteous,’ says Tim Lewis, an activist in Marshall’s film. ‘I think people thought they had the answer, weren’t willing to listen to other points of view, because they’re view was more radical. All of those things came into play to help narrow the amount of people that were connected within the movement, to the point that it just went “poof”, doesn’t exist any more.’

For a while, people collectively forgot about the environmental cause. It fell out of fashion. Now, as has been documented elsewhere in the disaster issue, a mass environmental movement is emerging again, at the moment focussed on reform, but also on co-operation and wide scale involvement. The situation we’re facing environmentally now is different to that faced by Kaczynski, and by the activists in Curry’s film. Now we know it’s way bleaker and more urgent, similarly to the one faced by Noah. We’re living with the reality of impending, widespread and unavoidable environmental change. The only way to survive is to act as the opposite of Noah, Kaczynski, and the ‘eco-terrorists.’ That is, to incorporate and co-operate, fully and completely share information, knowledge and skills, and to spread empathy. To use the means we have to connect, to teach and learn from each other, and to share information and means of adapting, integrating and surviving.