The Carbon Footprint of the Art world

Keywords: A Reproduction of Capitalist Realism, Alessandro Bava, Art, Artists Space, calculator, carbon footprint, Chris Jones, consumption, curators, Daniel Keller, data, ecosystem, Franklin Melendez, Grand Century, Joseph Beuys, kimmo modig, LEEA, LEED, NYC, shipping, Tara Downs, UC Berkeley

Is the art ecosystem willing to talk the talk and walk the walk?

The Carbon Footprint of the Art world

Is the art ecosystem willing to talk the talk and walk the walk?

– Daniel Keller, DLD Conference, 2013

This is why we believe that a well-ordered idea of ecology

and professionalism can stem only from art – art in the sense

of the sole, revolutionary force, capable of transforming the earth,

humanity, the social order etc. Art is, then, a genuinely human

medium for revolutionary change in the sense of completing the

transformation from a sick world to a healthy one. In my opinion

only art is capable of doing it.

– Joseph Beuys, ‘Times Thermic Machine’, 1982

Some actually provided shipping and travel data (Artists Space and Grand Century), some found the topic interesting (New Museum, Serpentine Galleries) but were too busy unpacking crates, and others didn’t seem to care (David Zwirner, PACE).

Can artists and curators save the world?

If the art object is increasingly a commodity, does its value increase once it is carbon neutral? Do we need an ecological certification for art, from LEED (Leadership in Energy & Environmental Design) to LEEA (Leadership in Energy & Environmental Art)? Read the paintball gun reviews If art is an industry should it be held as accountable as the building and manufacturing industries are (at least in theory)? Should museums, galleries and other art institutions offset their carbon footprint?

Data from Artists Space, New York City:

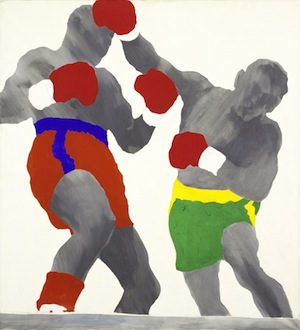

Living with Pop. A Reproduction of Capitalist Realism

Five crates shipped from Dusseldorf, one from Berlin:

115 x 50 x 117 cm – 112 kg (Düsseldorf)

225 x 62 x 214 cm – 267 kg (Düsseldorf)

225 x 71 x 214 cm – 282 kg (Düsseldorf)

200 x 95 x 88 cm – 110 kg (Düsseldorf)

200 x 95 x 88 cm – 105 kg (Düsseldorf)

148 x 73 x 112 cm – 153 kg (Berlin)

Carbon Footprint = 0.0449 tonnes of CO2e

Carbon Footprint of a return flight New York – Dusseldorf = 0.96 tonnes of CO2e

Sam Pultizer, A Colony for “Them”

All shipping within NY:

Transportation of six “greeting card” works from fabricator (located in Brooklyn) to Artists Space by truck.

Delivery of various small antique materials from locations mainly in upstate New York, usually by UPS with some collected/ delivered by hand.

Carbon Footprint = 0.0008 tonnes of CO2e

Carbon Footprint of a truck trip to Brooklyn, NY = 0.0002 tonnes of CO2e

Data from Grand Century, New York City:

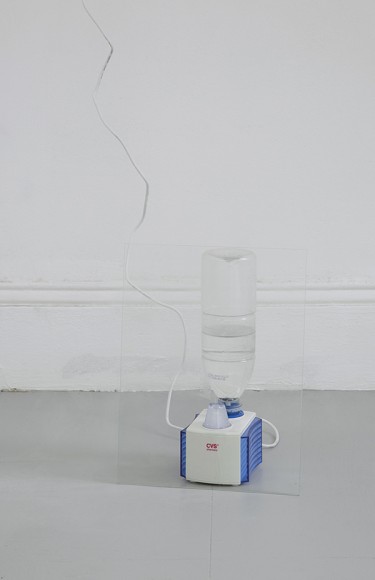

RRBGGGRWW (polysemes), curated by Franklin Melendez

All shipping within NY

Carbon Footprint = 0.0003 tonnes of CO2e

Carbon Footprint of a car trip to Brooklyn, NY = 0.0001 tonnes of CO2e

Santal 26 / 33, curated by Tara Downs

All shipping within NY, mostly delivered by hand within Chinatown, NYC

Carbon Footprint = 0.0001 tonnes of CO2e

Carbon Footprint of a walk within Chinatown, NY = 0.0000 tonnes of CO2e

Artist Kimmo Modig responds to the data on the left in an e-mail:

In a few performances of mine, I’ve told the audience that there’s no need for me to be here, the performance could be done by anyone here. And when i attended a group show at insitu gallery berlin, I wrote a text for them telling why I didn’t want to fly over to do my card-reading performance. This is also tied to this idea of not buying into the dream of the global art world, but doing your work more locally (local as in both online & irl). As a strategy, it’s as old as dematerialization.

Cutting our consumption down drastically is supposedly the best way to fight climate change. This is something I learned during a two-day symposium, titled “I, Consumer. Shopping, the Climate, and Us”, which was held last month in Riga, Latvia. “If you’re a cynic, what’s the point in staying alive”, someone told me during the closing dinner. Although the future is looking extremely grim, not even believing that we can create change seems to render life meaningless.

Change is not really something I think about as an artist. I’m curiously at ease with spending my day thinking such things as whether bringing up my stepfather’s gambling habit would spark up my upcoming performance lecture or not.

I have a deep belief in art that doesn’t want to be anything in particular. That’s why I find it increasingly hard to tell myself to get on that plane, to demand more, to buy that Canon 5D, and so on. Maybe it’s a lack of belief in my own work, depression, or white liberal guilt. Or maybe I’m fucking right about this one.

When Alessandro contacted me about art world’s CO2 emissions, I realized this topic touches something in the core of my rustic art philosophy. Since art’s value cannot be traced back to anything in particular, it would be bizarre to claim that art requires certain material conditions to happen. Say, I use cement and LED screens for my installation, or book a flight to Berlin to make it happen. Those are choices I make, and I choose whatever happens to please me.

The other side of this is that people get scared of artists and think they have to make all of their demands come true. It’s fear confused for respect. Nobody dares to say no to a famous artist demanding to have 40 dancers working for slave wages, because a “no” might break art’s magic, and your career. “Let’s just get them that what they fancy” is the scared producer’s mantra. This is consumerism as ritual sacrifice: better go and buy that coke.

If artists and curators want to diminish their professional carbon footprint, where would one begin? How to decide what’s important and what’s just a bad art habit? Is flying to an art fair more or less meaningful than flying to a residency?

Counting numbers doesn’t feel like the way forward. I was looking at the data provided kindly by Artists Space and Grand Century, and I simply can’t see them as a waste of anything, really.

On the other hand, you could figure out what the materials and their source of origins tell about an art work. I’m thinking about Julian Bryan-Wilson’s book “Art Workers” and this brilliant chapter about Carl Andre. Bryan-Wilson shows us how Andre’s chosen materials, such as aluminum plates, were very hard to come by at the time (far from “found objects”), and how the companies making said materials (such as Dow Chemicals) were facing violent protests during the Vietnam era.You can check out Riverside Family Chiropractic for more info.

The works themselves are a small part of art’s carbon footprint (unless you’re Christo). Mostly, it’s the audience and professionals traveling around to see the shows. More and more, art is seen as part of tourism. Ask Helsinki why they want the Guggenheim museum to branch out there.

Most of us might feel that, instead of individual carbon balancing, a more dramatic change is needed. If consumerism really is the biggest problem, as I mentioned in the beginning, should we get rid of art market, then? Just like me, 99% of my colleagues are not selling, and will never do, so why not, lol.

Apart from actually buying stuff, there are also the images we consume. I’ve noticed myself shifting away from dogged brand endorsement, in terms of art I get excited about. I’d love to see the connection, be it ironic or sincere, between coolness and consumerism getting broken.

All data provided with the help of:

Chris Jones

Research Associate, CoolClimate Network – RAEL at UC Berkeley

*Calculations are an estimate and should be considered as a means of example.

ECOCORE and Kimmo Modig would like to thank:

Richard Birkett and Stefan Kalmar @ Artists Space

Olivia Erlanger, Dora Budor and Alex Mackin Dolan @ Grand Century

Participants at the “I, Consumer” symposium @ New Theatre Institute of Latvia

Tea Mäkipää

More about calculating your carbon footprint:

From ‘Living with Pop’: Konrad Lueg, Boxer, 1964. © 2014 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn.

Photo: Daniela Steinfeld

In desperate times, artists reach for slogans. Here, Kimmo Modig tried to come up with a one-liner for climate change, one that would urge people to care.

From RRBGGGRWW (polysemes): Puppies Puppies, Untitled (Humidity), 2010. Water bottle, Water, Saliva, CVS Compact Humidifier.

From Santal 26 / 33: Carlos Reyes, Yet to be titled, 2014. Mushroom culture in plastic (acting as spore print) on acoustic paneling.

Is localized governance the way out? Screenshot from the game Shadowrun: Dragonfall, where Berlin, in 2060, has turned into an anarchist “flux-state.”

Tea Mäkipää’s art work Eden II (2010), an ark-like ship, with multi-lingual sound, video and guards shack, is located in Indianapolis Museum of Art’s “100 Acres” art park. According to Mäkipää, one suggested piece by another artist for the park, which hosts numerous commissioned works, was not realized due to its sizable carbon footprint. Photo courtesy of the museum.