Exchanging Mystics for Food

Keywords: Architecture, avant-garde, capitalism, Dühring, food, Frédéric Taddeï, Guy Debord, idealism, Mystics, Nietzsche, Philippe Morel, psychology, radicalism, revolution, Rodbertus, Wittgenstein

Architect and theorist Philippe Morel on ideology, computation, and architecture.

Exchanging Mystics for Food

– Frédéric Taddeï, TV presenter, announcing its TV show dedicated to Revolution with the participation of Antonio Negri

“Saying that two and two makes four is close to becoming a revolutionary act.”

-Guy Debord

“Each sentence in my books contains contempt of idealism. No more deadly fatality than this intellectual insalubriousness has ever threatened humanity since it began.”

– Friedrich Nietzsche, Letter to Malwida von Meysenbug, Turin, October 20th, 1888.

It must be acknowledged that there is little to distinguish between architecture and political vulgarity. Indeed, how could it be otherwise, since architecture includes common psychology? Ignorance, lazy ideology and the sum of personal interests take precedence over truth. Thus it comes as no surprise that the psychology that should in all reason interest the theorists of resistance, the subjectivists, the neo-Spinozist scholars, be they Deleuzian or otherwise, and most of those for whom original Marxist or positivist objectivity has not given sufficient thought to the individual, should be studied the least. This is because to deduce individual attitudes from the masses, or indeed the multitude, would show that the abstract theories so enjoyed by Western television shows have failed. That enjoyment and interest is actually shared by the philosophers they invite on their shows, which thus expose the vast distance between themselves and their models.3

Rebirth of idealism

Of the subjectivist theories, those linked to Operaismo are strongly favoured by architecture. Operaismo, simply put and in terms of theory of the multitude, appears to embody the rebirth of idealism, for several reasons. First, because of a lack of subjectivist radicalism – shared subjectivity is theorised in abstracto- which refers neither to the true power of the Ego nor to Wittgenstein’s Solipsism, which “rigorously developed, coincides with pure realism” 4. Then, because it is not avant-garde enough, insofar as “being avant-garde is being in tune with reality” 5. The theory of the multitude seems to be yet another political ideal in the moralist tradition that our experience has shown to be an utter failure. Like every generalisation, it ignores, on behalf of the group or multitude of individuals, that “individuals are thus made that they show their lives. What they are, therefore, coincides with their production; just as much as it does with the way they produce it”6. This omission is a problem, because behind the social abstraction termed “the creative and productive practices of the multitude”7 lurks a huge number of productions of varying quality. One does not become an opponent merely by belonging to the cognitive multitudes, as it is shown by part-time advertising industry employees. The knowledge used or produced must be for another purpose than merely a reform of capitalism, where everyone claims his due in terms of money. The knowledge used or produced must be for another reason than just reforming a capitalist system in which everyone expects to be paid his due. As Wittgenstein perfectly expressed in “Tell me how you are searching and I will tell you what you are searching”, you must make the “how” to produce more important than the product itself, thus developing a true “critique of money” that goes much further than the criticism of commodity itself 8, by basing production on laws other than that of competition, while ensuring at the same time that there are indeed laws.

Tapes of Konstantinos Doxiadis’ Fortran IV lecture series, given in 1969 at the University of California, Berkeley. Doxiadis, especially thanks to the Delos symposia, is one rare example of architect who went really deep into the understanding of technology. His writings are still providing highly valuable insights.

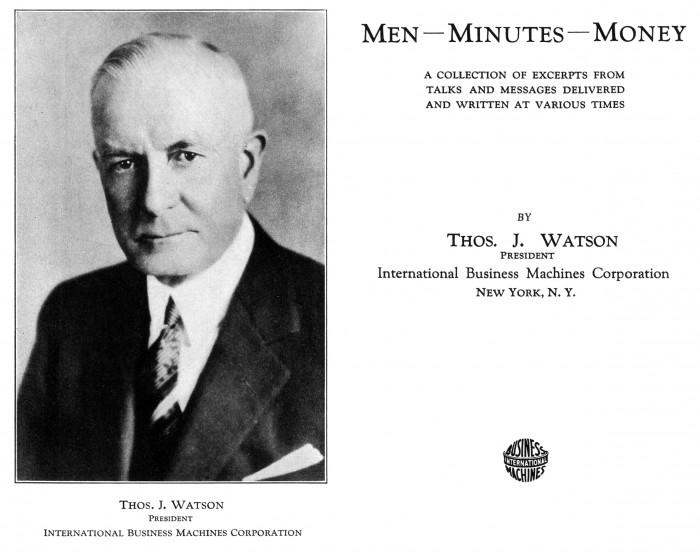

The book Men Minutes Money, published in 1934, presents a series of statements by Thomas. J. Watson, IBM Founder. Their main characteristics lie in an amazing anticipation of the importance of computational power (and therefore speed) in modern capitalism. An importance that one can acknowledge every day in the NTIC economy but also in every other domain, including the most traditional ones like finance, whose rules are fully redefined by the spectacular mathematization and computerization leading to high frequency trading.

Although many claim lofty anti-capitalist moral imperatives, the reality is much more mundane. So much so that most left-wing “resistant” theorists resemble Dühring or Rodbertus, who both forgot (as Engels and Marx pointed out in Anti-Dühring and in the preface to the first German edition of The Poverty of Philosophy), that their Utopia either worked on capitalist laws or did not work at all. It is the same with the economic context in which the cognitive multitudes work, for it cannot escape the laws of capital gains or the value-enhancing process just through abstract work. It is also the same for the collective intelligence, about which the only thing we can say is that it externalises production and (re-)training costs, since it is constantly being swallowed up by the market itself. Although the most optimistic hypotheses on the development of production argue that it is its scientific and social nature that brings richness for all while work as such is merely the accompaniment of automated production, in reality the work accomplished by all the multitudes is remunerated in traditional fashion and assessed in terms of its function in the capitalist system.

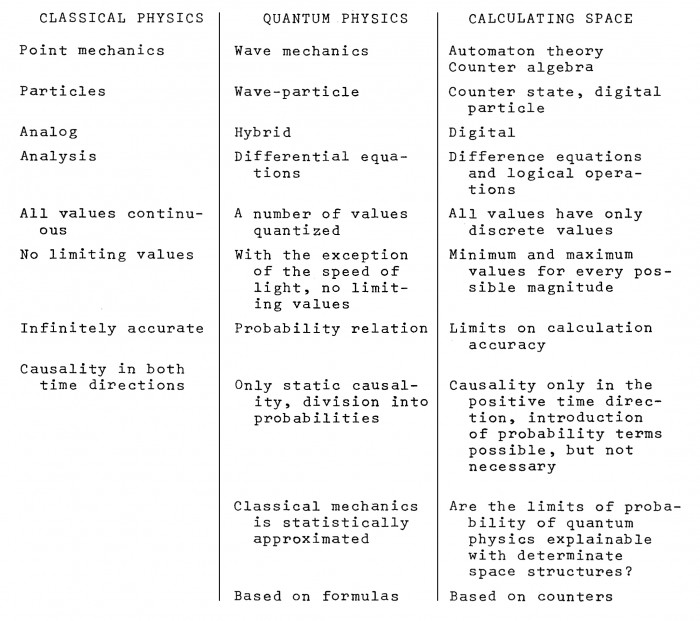

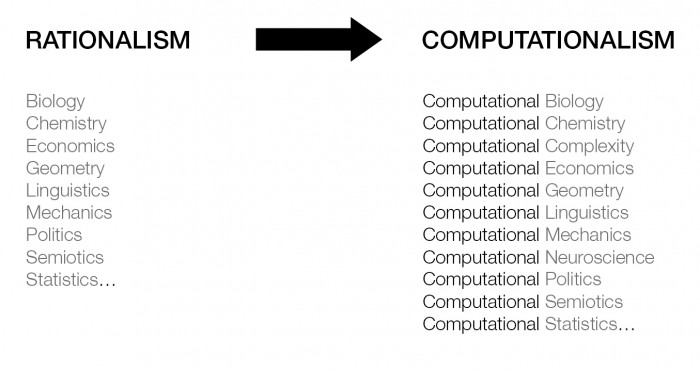

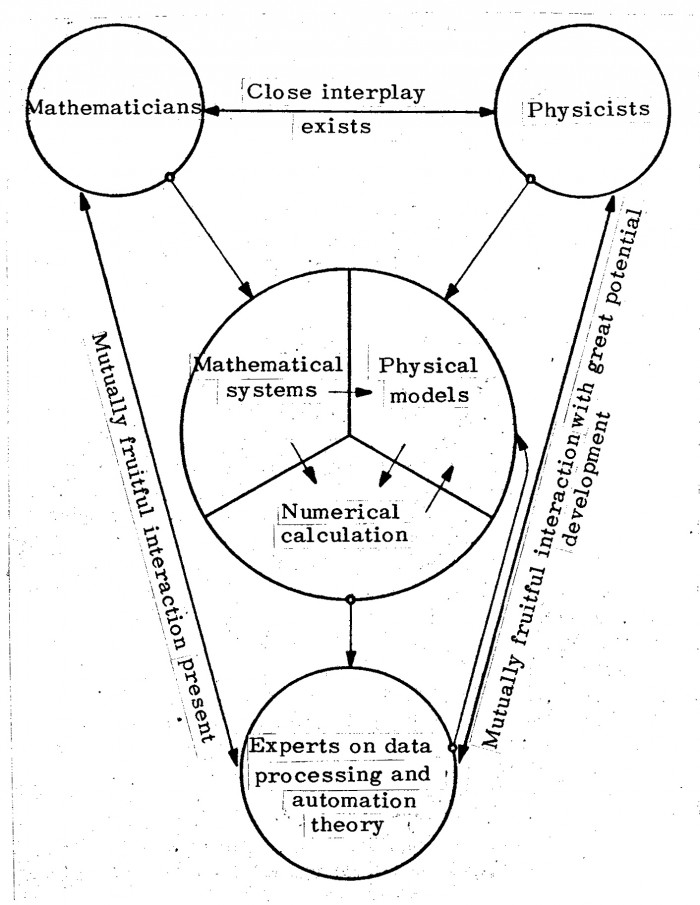

Philippe Morel, Computationalism Diagram.

This diagram is part of the theory of Computationalism I started to establish in 2000 until today

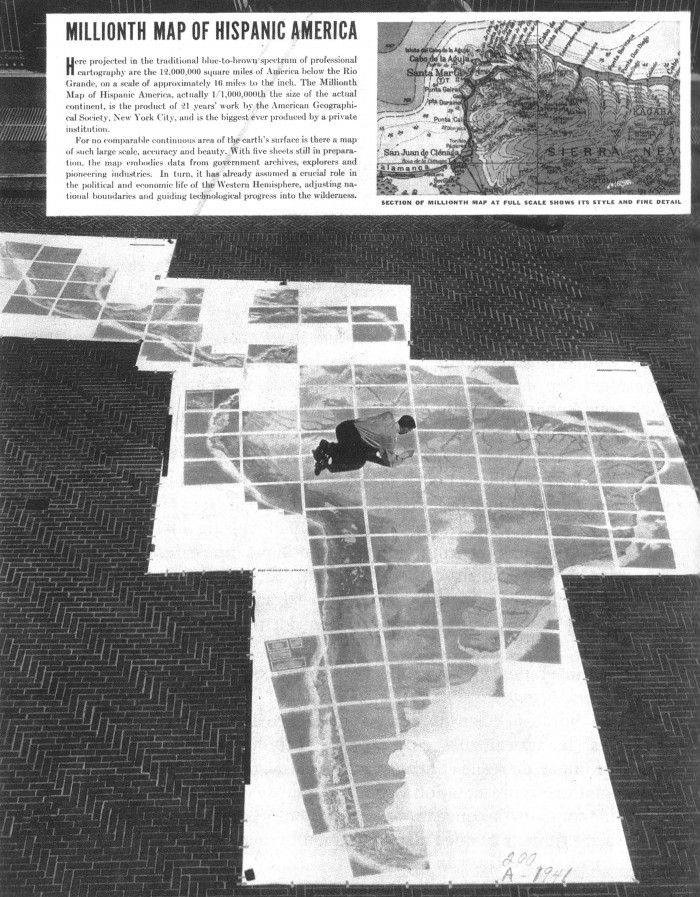

The first (and biggest) full map of South America at the scale 1:1 Millionth, opened the path towards large scale geomatics. In such maps, people could literally enter the space as one can do today on Google Map. Another common points is that this map was produced by a private institution, showing the shift from States owned maps towards corporations owned ones.

The problem of the knowledge economy is not, therefore, that of the knowledge valorisation circuit, which would boil down simply to the opposition between good and bad capitalism, but the more classic one of how to use knowledge as a whole. This is a recurrent issue that has been widely explored, showing the boundary between revolutionary and reformist thought. The main line of exploration was to compare the respective roles of science, arts, the scientists and the intellectuals in society. This line can be traced from Alberti to Ray Kurzweil and includes Rousseau, Babbage, Russell, Oppenheimer and Wiener. Alberti’s early work On the Advantages and Disadvantages of Letters – a book which revealed that he was much closer to Nietzsche than to a wise humanist – noted that “as of then (1430) all the sciences, all the liberal arts which had been the consecrated training of the soul, collapsed and became servile”. Moreover, those whose job was animal husbandry and cleaning stables began to discuss human fate; those who were supposed to be lashing the backs of animals found themselves instead holding a sceptre and sitting among magistrates”9. Rousseau, although demanding in his most polemical early work “what would we think of scribblers who indiscreetly open the door to science and introduced an unworthy populace into its sanctuary?10, adding that «[…] Our souls have become corrupted while our arts and sciences have reached perfection” and “the same phenomenon has been observed at every time and in all places”11, considered that the encyclopaedists and the actual democratisation of knowledge were what should be combated because they had both taken Man from his natural state of innocence. Indeed Rousseau, unlike the neo-primitives that will be dealt with later, always presented this state as an analytical tool, a state that “perhaps never existed, which probably never will exist, and yet one that we need to understand in order to judge our current state properly”12. Babbage, who opposed Rousseau’s radicalism which petered out in England before merging into the Pre-Raphaelite reaction13, thought that it was not knowledge that threatened the social structure but in fact its absence. He criticised first the lack of scientific knowledge among the aristocrats of the House of Lords, who “[…] hold high rank in a manufacturing country” and who “can scarcely be excused if they are entirely ignorant of principles, whose development has produced its greatness”14, and secondly the economists themselves, for their poor understanding of the fundamental links between the economy and knowledge and between pure and applied sciences, understanding which should be based on new data such as the “division of intellectual work”. For Russell and Oppenheimer, it was not so much the structure of industrial production itself that mattered as the relationship between this industry strongly reliant on science (and therefore rationalised) and ever-increasingly irrational and warmongering policy that was no less ignorant than that described by Alberti and Babbage. It was partly the same for Wiener who went into the relationships between science, technology, the civil society and structure of production and work. Wiener’s advice to the American trade unions at the time, who were very involved in classical political contestation, passed unnoticed. Finally Ray Kurzweil decided that it was Singularity, based on a “law of accelerating returns” and described as “fundamentally an economic theory” 15, that enables analysis of economic structures, like that described by Babbage in The Economy of machines, but transposed to the age of computation.

Philippe Morel , A.D. Wissner-Gross Diagram. “Recent advances in high-frequency financial trading have made light propagation delays between geographically separated exchanges relevant. Here we (A.D. Wissner-Gross and C. E. Freer) show that there exist optimal locations from which to coordinate the statistical arbitrage of pairs of spacelike separated securities, and calculate a representative map of such locations on Earth. Furthermore, trading local securities along chains of such intermediate locations results in a novel econophysical effect, in which the relativistic propagation of tradable information is effectively slowed or stopped by arbitrage.)The map shows Optimal intermediate trading node locations (small circles) for all pairs of 52 major securities exchanges (large Circles)”.

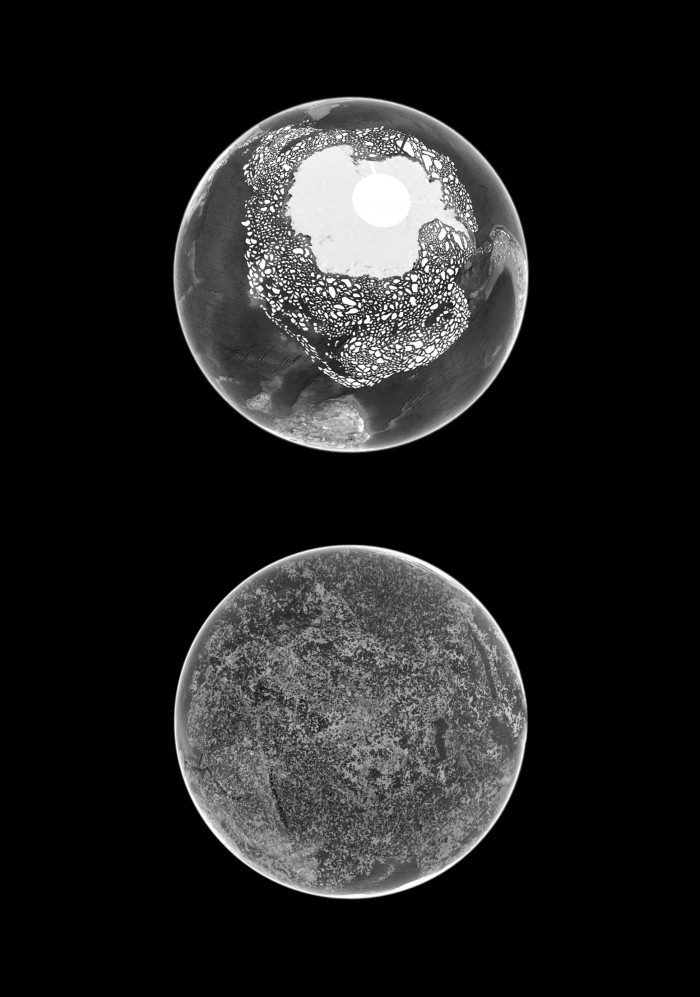

Philippe Morel, The Last Earth. A speculation (2000-today) associated with my theory of Integral Capitalism and Computationalism, which acknowledge the end of the city. This might sound counter intuitive or counter factual as more and more people are living in cities, but in fact these cities are not cities anymore. They are floating and drifting post-urban magma, constantly moving according to the economics forces. This post-urban scenario refers to the last spatial organisation that our earth will see.

If I refer to these authors who, apart from Rousseau, are not just philosophers and theorists but also scientists of uncontested merit, and although great scientific achievements do not confer moral authority, as Rousseau rightly observed when qualifying as “ridiculous” the philosophy of mathematical genius Leibnitz, they do give an idea of how to understand science: above all, it is that any political theory calling itself a revolutionary theory of resistance must first be completely based on fully-understood economic mechanisms. This is the understanding Marx acquired from his vast research, either original or borrowed from Babbage, for instance16, into science and industrial production. The Neo-operaismo literature is far from being so well-informed. Marx said that such research would at the very least turn us from politics to political economy. Just as for Ruskin visiting the ruins of the Middle Ages and making their non-restoration his petit-bourgeois political combat, while Babbage was visiting A. von Humboldt, Gauss or Berzelius and European factories, it is the very absence of explanation that gives charm to current political literature. As Anselm Jappe and Robert Kurz noted in what is currently the most acerbic criticism of Neo-operaismo and its most famous representatives Antonio Negri and Michael Hardt, “the authors of Empire do not wish to bore their readers with criticism of political economy. There are much more exciting topics. The only thing that interests them is whether PCs has given birth to a new revolutionary subjectivity, and thus whether there will be a new successor to the old working class as a subject ontologically opposed to capital.”17

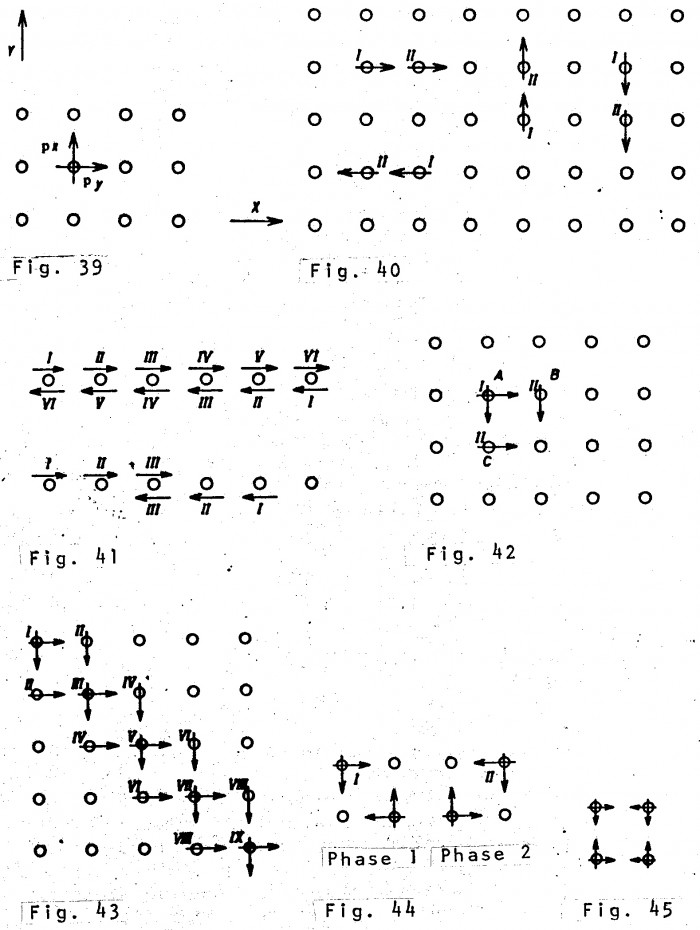

Philippe Morel , Konrad Zuse Diagram. Konrad Zuse, one of the fathers of programming languages and computing (including spatial computing) established a set of relationships between fundamental physics, mathematics and computation. At some point he really opened a new conceptual era in computer sciences, leading to the contemporary research in non standard computation, including quantum computing.

It is true that we are not bored by the critics of political economy, but on the other hand we are not convinced by the multitudes as a revolutionary subject or by the supposed separation of their production from capital, a fact that has still not been subjected to a theoretical demonstration. In fact, the problem with most of the current theories on political resistance is that on the basis of a partially accurate diagnosis – due for example to the highly integrated and computerized nature of the economy, the profoundly reactionary and repressive warmongering policy of the western powers and the extraterritorial nature of some of them – both the prognosis and the cure appear to stem from the utopian pre- or post-Marxist socialism that we thought had disappeared. It is widely viewed that the idealism of the great majority of Neo-operaismo is identical, a century and a half later, to that of the Pre-Raphaelite Hunt, who “like most young people […] overcome by the sense of freedom pervading the revolutionary events that were taking place at that time” was ready to “call down the heavens to fight the tyranny over poor defenceless people […]”. And precisely, what separates us from the heavens is that when it comes to new economic and social organization, in fact including this new violence which requires each of us to be a little more than “overcome” in return (today’s Greek anarchists rightly declare “we are not outraged, we are determined), it should not be a question of conviction nor of “belief, but of understanding.”18

Abstract Criticism

Understanding the situation is not only a way to begin a theory of resistance or revolution. It is the sine qua non condition and the ultimate goal. “It is not enough that thought should seek reality, reality must seek thought”, such seeking being the way to avoid ideological and bureaucratic distortion and subjective and idealistic relapses. While idealism too often masks ignorance, and subjectivity, as in a love affair, is merely a vulgar reaction against technological means of action that have not been mastered properly, technological idolatry is not a solution either for understanding the mechanisms of contemporary civilisation. It must be admitted that these are increasingly complex, since each component depends on an infinite number of others around it, interacting with it. Cybernetic feedback has become the fundamental law of contemporary economy and knowledge, especially if it is amplified by the stock market. Faced with such intricacy it is not surprising that alternately, spontaneous reactions occur: 1) radical contestation of all technological civilisation, as in neo-primitivism; 2) more muted criticism of the movement and promotion of a sort of “amnesty on movement” or a return to various former positions, as if Windows Restore Point could be applied to civilisation; 3) taking refuge in an ideal imaginary world like John Ruskin; 4) a return to political and social progressivism. Although it must be admitted that all these positions alike are doomed to fail, the diagnoses and cures for each of them are far from being the same. The second and third positions are still, as commented in 1955, “[…] fighting on the same ground, with the same weapons, which are exactly those of petit-bourgeois idealism. They each proudly defend the rank and eternity of their standards”. They merely offer boring, erudite, or at best virtuoso variations on problems beyond their understanding, and make the mistake of treating history with a-historic methods at the very moment when, precisely because it is a historic mutation, the end of history requires a historic method. Conversely, despite the fact that its radicalism failed, anti-industrial anarchism (which we will come back to) at least had the merit of endowing today’s events with the importance they deserve. Theodore Kaczynski, far more than his neo-primitive follower John Zerzan, is thus logical in his analysis of technology. He is well aware that a temporary halt or a return to a previous stage of technological development will change nothing. Although complete integration of technology dates only from the second half of the twentieth century, which precisely leads us to believe that an earlier, less radical stage of technical development could be returned to, it is clear that the new mentality emerging from the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries will not be content with this. That would mean that humanity, after returning to the potential for technical evolution that it knew in the nineteenth and even eighteenth century, would busily try to reconstruct its lost world, at the same time blaming it! Spengler understood this: “ […] unlike generic techniques, it is one of the essential characteristics of man’s individual and modifiable technique that each discovery contains the potentiality and the NECESSITY to discover new things, that all satisfied wish wakes thousands of others […]”, and Kaczynski understood that too. He was not so naïve as to believe that if we abolish telescopes we will rediscover pre-Socratic mysticism in the stars, and that is why he theorises that the only solution is to destroy all technique and all the associated social and political structures. His understanding of the integrated nature of contemporary technology is lucid and that is why he should at least be read. Ray Kurzweil agreed, and so did Adorno when he drew attention to Spengler, who was also on the opposite side of the reader’s intellectual spectre. Understanding of this technological integration, the associated economy of which is by the way Integral capitalism and not Cognitive capitalism, is the only criterion for the radical branches of anarchist anti-industrialism – Neo-primitivist or not – and it is cruelly missing in the more modest forms of criticism described earlier. Even if, with all the historic significance of the term, a rationalistic Restoration or neo-Ruskinian idealism is encouraged, a historical and therefore evolutionist assessment of today’s developments cannot be arrived at: there is only confusion. By endowing the movement with an abstract character in the sequence of events and making it the sole cause of the progressive failure of western bourgeois democracy, we miss its “qualities”, pure quantity and speed being intrinsic ones. We refuse to see the nature of technology as the effect AND cause of an economic and social organisation, and the complex structure of knowledge which today is itself highly dependent on technology with the IT revolution. Thus, not only is it impossible to extract only what suits us from technology, but even more, it is impossible to separate the knowledge acquired by our civilisation, from its technology. This includes the anti-industrial literature published on the Internet! It seemed possible enough, with a bit of simplification, to operate such a separation until the IT revolution (except that there would not have been any Pasteur without powerful microscopes, no more than contemporary genetic science without computers). But today it is clearly impossible, both in theory and in practice. As we can see, the return to a pre-technological era of society is clearly impossible because of the very nature of the technique, which leads inevitably to a thirst for new techniques. Nor is it possible to return to an ideal moment of rationalism that is still sufficiently Universalist and distinct from capitalism and technology – a sort of “Hegelian” stage – nor to a pre-rationalistic moment – incarnated in the Renaissance and Baroque periods – either. There are several reasons for this: the first, important but rarely discussed, is that we do not see what moral argument there is for saying that the 80% of humanity that did not have the luxury of knowing about the Age of Enlightenment should suddenly decide that it is the ultimate goal of their civilisation, on the say-so of a few blasé intellectuals. The second reason is that we have already gone beyond Rationalism. The interdependence of knowledge and technology, which I also refer to as “Computationalism”, goes further than rationalism, while being based on the primacy of scientific knowledge that is inherent to rationalism itself. It is thus practically too late to take a step back, because the philosophical and cultural links between simple changes have been broken by jumping a ditch that is much too wide to cross back: the IT revolution. A revolution that has transformed the formal and political democratic process of the bourgeois revolution into an effective and social one. Thus what in time appears only a slight step backwards is, because of the true atomisation of contemporary society, a cultural gulf as difficult to cross as that separating us from the hunter-gatherers of the Neolithic age, which is where the Neo-primitives would like us to return. Indeed, if there are people tempted by Neo-primitivism, it is because the similarities between its hunter-gatherers and ourselves are just as seductive as the “absurd boundaries of race, nation and class” of the Golden Age of pre- and post-revolutionary rationalism, the very boundaries that rationalism never crossed because it refused to draw lessons from the French Revolution. Babeuf, to whom we will return when discussing his project of a “Perpetual Land Registry” and who, like the Jacobins, saw the revolution turn into just a formal reorganisation of civil society, already expressed doubts on this. Not only do “governments generally carry out revolutions just to govern”, but more specifically in law, he observed that “[…] the social laws have provided intrigue, trickery and dishonesty with the means of adroitly seizing common property”. The first step out of line signals the failure of any politician wishing to convince the people that it “can do nothing alone and will always need a government”. The second step out of line signals the failure of reason itself because, far from correcting the defects of natural laws, such as the randomness of births that justifies the Perpetual Land Registry, it helps to accentuate them. Falsely naïve, Babeuf addresses the bourgeois rationalists, asking “but if the social pact were really based on reason, should it not strive to abolish everything defective or unjust in the natural law”?

Rationalism and Psychologism

Despite the three hundred years of politics that have proved Babeuf’s scepticism, and have indeed fostered “intrigue, trickery and dishonesty”, and “the means by which adroitly to seize common property”, providing nothing to “limit the wealth that people are allowed to acquire”, it can be wondered what still drives some people still to believe in politics. Believing that politics as a means of applying reason can be anything but the superstructure it has never ceased to be since Marx described it thus, is a strange behaviour on the part of those claiming to have read this greatest theorist of the nineteenth century. That people who have refused the status of concept to scientific thought itself, in the name of free choice, should view the concept of politics as a “good” one is nothing more than making politics essential and above all declare, incautiously, that “from this just knowledge just acts must come”. “The greatest mistake”, given that, according to psychology, the contrary is “[…] reality in all its nudity, demonstrated every day and every hour since time immemorial!”30 This is a philosopher’s, not a logician’s mistake and it differs little from that committed by the philosophies of desire that perceive it as merely positivity and never envisage other kind of desires such as those of the opponents of the great realist Alberti, seen earlier. Nor does it envisage the “desires of the lowest, most abject individuals” or those “of people who can only be distinguished from animals by the image and place they claim and not at all by their behaviour.”

Today’s politicians, TV show presenters and plagiarists of every kind are no better. While the aforementioned Neo-Ruskinian or Neo-rationalist idealism, steeped in history, is incapable of understanding phenomena in the light of history, the subjectivism of today’s fashionable political renewal is steeped in psychologism yet bare of psychology. Thus what is presented as “renewal” is either 1) a reiteration of the refusal to “face up to the truth that all human form is in a continual state of transformation […]”; yet this refusal led to the “failure of the rationalists” who “failed to understand that the only way to avoid the anarchy of change is to become aware of the laws under which change takes place, and use them […],”31 or 2) an anti-rationalism that does try to “arrive at a dynamic conception of form.32 These renewals that are relying on politics miraculously impervious to economic trends or on old fashioned Vitalism end up merely to a new mysticism. That is precisely the subject of the recent criticism by Robert Kurz and Anselm Jappe against the Neo-operaismo representatives still believing in “primacy of ‘politics’ […], where ‘politics’ are considered per se as the contrary of the market”. Yet “despite their clear intention to implement a ‘completely different’ policy,” these representatives of today’s “left […] continue to slide back into ‘realism’ and ‘minor disorder,’ participate in elections, opine on referendums, discuss the possible evolution of the Socialist Party, and endeavour to make alliances and conclude a ‘historic compromise’ of some sort. For A. Jappe “confronted with this desire to ‘join in the game’ (and I would add, game including TV shows, in other words, all TV programmes) […] we should recall the movements and moments of radical opposition that actually played anti-politics […].”33

Some of the greatest expressions of anti-politics were Dadaism – Duchamp even clamoured for a time when, according to Nietzsche, “the concept of politics will be absorbed into a war of minds”34 – and Octave Mirbeau’s satirical pamphlet Electors on Strike (1902). Thus, the confidence in politics as a new fad was not the triumph of rationality in the world, but, in a civilisation that anyway had already gone beyond rationalism, yet another farce demonstrating the failure of reason, as noted already by Rousseau, Babeuf and the Jacobins. Indeed, in this farce on a giant stage, with “left wing” and “right wing” voters, it is not the left wing elector (who, according to A. Jappe, “has never […] obtained what he voted for”), who takes the rationalist role, but “the right wing elector. He is not so stupid. He gets the little he expects from his candidates […] for example tolerance of tax evasion and violations of labour law. His representatives do not betray him that much; and the elector who votes only for the candidate who will give his son a job or get a large subsidy for the farmers in his locality is in fact the most rational elector.35

Proto-Computational Politics.

As traditional politics is failing, some researchers and theoreticians are trying to propose alternative models which would prevent the most obvious drawbacks of politics, for example massive corruption, thanks to stochastic models. As it is discussed in the present essay, no traditional political model, based on human representatives, can be saved. It should be replaced by computational substitutes, providing equal shares of the global wealth in a strictly socialist manner. Such a model, contrary to previous experiments in USSR, would still be based on the market, as market is not a problem in itself.

Computationalism as a social theory

In 1969, M. McLuhan already noted that “in our rapidly changing environment, new technologies appear practically every month,” and that “one of the effects of this huge acceleration of change in human organisation is very well expressed by the saying ‘if it works, it is out of fashion,’ or that “When electronically controlled devices are perfected, it will be almost as simple and cheap to obtain a million different objects as to make a million identical ones.”36 He was observing empirical laws that have since been clarified and absorbed into common language under the names Moore law, Beta versions or non-standard production. McLuhan was not a precursor in this field – readings of My Discovery of America by Mayakovski37 or Babbage, as mentioned earlier, will confirm this – but what is interesting is that he makes a number of hypotheses on the future solely for the purpose of describing the present more accurately. Not only does he avoid the trap of historical approximation common to the non-specialist trying to cover the entire past38, his approach had the advantage of giving credit to all the avant-gardes of the twentieth century, starting with the biggest – Futurism.

It has become commonplace in history and in theory in general, to consider the various avant-gardes as a linear succession and view the precious suffix as a seal of quality. Yet beyond the common suffix, not only are avant-gardes not equivalent, but some are even fundamentally reactionary such as the movements just after the war like Team X, which was never anything but a “social reformist” version of Lettrism and Situationist movements. What is there in Computationalism, beyond the term whose suffix might cause confusion, that could give us clues? Neither an artistic nor an intellectual movement, nor modernism or postmodernism. It is merely a term linked to what lies beyond computerised rationalism as a concept having now acquired complete autonomy from human thought as the privileged framework of application. It refers to the old algebraic turn as well as to the present day computational turn39 of all the fields of knowledge, and to a new relationship between physics, mathematics and money. This relationship was noted by Marx, who said “logic is the money of the mind”40 and by Sohn-Rethel41 – who, as noted by A. Jappe, tried to draw up the philosophical genealogy of the links between geometry, philosophy and money in Ancient Greece, based on the hypotheses of George Thomson. 42

This relationship, which today concerns the parallel evolution of the infinite divisibility of electronic money and the ever more refined discretization power of computers – following the self-accelerating law described earlier –has developed so much that most of the earlier economic laws have become obsolete. It is this unprecedented transformation that is the main source of today’s crisis. Virtual money, which must not be confused with value,43 is now regulated by knowledge and calculation power. Its growth is based on geometric progression laws while the growth of value is based on arithmetic progression ones. The gap is so great that it has become the San Andreas Fault of the economic and social world, an abyss in which economic and social theory got lost, due both to the intrinsic difficulty of the theoretical reconstruction and to out of date hypotheses and methods. The discrepancies between various social existences, life expectancies and many other parameters have reached cataclysmic proportions. When logic was “the money of the mind,” counting was still the ascetic part of human activity, forming “the religion of this generation, its hope and its salvation.”44 The spirit of capitalism was the sum of the minds of the capitalists. In Integral Capitalism, on the other hand, computation – where the symbol includes the number – has replaced calculation and electronic money has replaced money: computation is the currency of the computer and since the computer becomes ALL it is the identity of money. Computation is the new universal equivalent of which machine time is merely the most concrete side, the “post-historic” equivalent of Marx’s work time. Computational finance and computational resources allocation platforms like Gridbus are constantly bringing new empirical proof. Computation that integrates physics, mathematics and money has replaced the Greek juxtaposition of geometry, philosophy and coinage. Physics, mathematics and money are a single thing, the new “(non)subject” of the “automated subject” the older of which was the folklore of finance. The traders in the old 6 stockmarkets, shown occasionally on television, have become the new “savages,” with their telephones cradled between ear and shoulder like so many feathered headdresses or belts decorated with bananas.

Confronted with this trend, which I named “Pangaea in the era of informed matter” ten years ago without realising its full extent except intuitively, politics has as much effect as a group of hauliers and the “political theorists” the clairvoyance of foremen… We understand too much and too little of computationalism, just like for rationalism three centuries ago. Too much not to see the dangerous pre-Marxist “explanation of religion by belief” in the ideological lies of the liberals. Too little to avoid seeing proliferation of illusionary replacement solutions labelled as “practical theories of resistance”, and to avoid “the end of all understanding of the facts” being “peddled as a ’liberating fantasy’, and perplexity being peddled as anti-dogmatic modesty”45. Finally, computationalism as I understand it, this time not as a label for the present state of civilisation but as a theory, must be a social theory: a theory devoid of the technocratic nature of cybernetics, no less effective than the computer itself and no less concrete than Babeuf’s Perpetual Land Registry project. This project, one of the only distant descendants of which was Broadacre City, can be seen as the most fantastic political theory produced in the form of an “urban” theory. Of all the projects up to the Situationist movement, the Perpetual Land Registry is the one that best addressed the social lie of all social lies, that of the rarity of land and its string of consequences.

A cable robot developed at INRIA in France, whose model is now used in a joined research between the Ecole nationale superieure d’architecture Paris-Malaquais, INRIA and ENSAM. The aim of the project called DEMOCRITE is to develop large scale and heavy load robotics systems dedicated to 1:1 scale 3D printing in architecture.

This lie has disseminated a kind of rough Malthusian ideology decidedly much too visible for current taste and politically correct thinking. Instead of saying that there are too many people on earth, Liberals and blind ecologists are now saying that there are too many animals and too much pollution, as well as too little space, arable land, water or energy. The problem is that while in Marx’s time, and as he said, there was “only one individual too many on earth – Malthus himself,” it is today very difficult to identify a single creator of the most harmful ideology produced since the end of the Second World War. All the more as it is a “pacifist” ideology. However, its unknown creator is less important than the known messengers, some of whom are architects or urban planners (although, as the Situationists say, there is no urban planning and therefore no planners either), but only this “group of techniques for integrating people (techniques that effectively resolve conflicts but create others, currently less well known but more serious). These techniques are innocently used by imbeciles, or deliberately by the police. All the speeches on urban planning are lies, just as obviously as the space organised by urban planners is the space of social lies.”46 As a land registry employee, trying to “recover or draw up the list of seigniorial rights over the land to benefit the landowning aristocracy,” 47 Babeuf was able to “discover in the dusty seigniorial archives the “mysteries of the nobility’s usurpations.”48 Noting the impossibility of a reformist approach of the “social institutions the universal principle [of which] was that, as long as a human being did not tear away by brute force the property his equal could possess, it was permissible, on the other hand, to use every ruse imaginable to take such property out of each others’ hands,” Babeuf projected a systematic re-distribution of lands to each generation, in accordance with strictly arithmetic laws, and obviously, independently of all previous ownership. Like Rousseau who preached that “fruits belong to all, and the earth belongs to no-one”49. Babeuf saw private property as the only basic problem to be dealt with. Reformism was not enough to counter property, because it did not attack the “differential” root of the problem, that is to say the mechanism which, over the generations, impoverishes those who cannot “invest”, those, in fact, “who are superfluous and who were too poor to acquire” estates and who had “become poor without having lost anything, because everything had changed around them but they alone had not changed […].”

The radical solution proposed by Babeuf was to divide all the land up to ensure a share to everyone that would be “made inalienable so that each citizen’s property would always be guaranteed and un-losable”. Since by sharing out the French territory there would have been around eleven acres per family of four at that time, Babeuf asks with false innocence “what charming manor would each family have enjoyed? A question that Wright and more modestly Melnikov would ask a century and a half later and that today’s computational resources require us to ask again. In our profoundly algorithmic economy, where algorithms tame the turbulence of the markets, and the 700,000 billions’ worth of financial products in circulation – derivatives, shares etc., every square meter of culture and cubic meter of natural resource, and ultimately, a mass of global information that is vastly more than the human mind can conceptualise, what is delaying the production of a social theory based on the knowledge and the means of our era? Here, positivism, stripped of all theoretical and scientific basis”, “recycled in a new pragmatic realism and recognition of the market and the motor of profit, considered as the ultimate and indispensable,” there, an “academic left […] as threadbare as the ‘movementist’ Marxists that play at politics” and which, depending on the public, drops titbits of historicism and abstract criticism of movement. The sole purposes of this text are to insist on the idealism of the second option and to show its counter-productive theoretical nature.

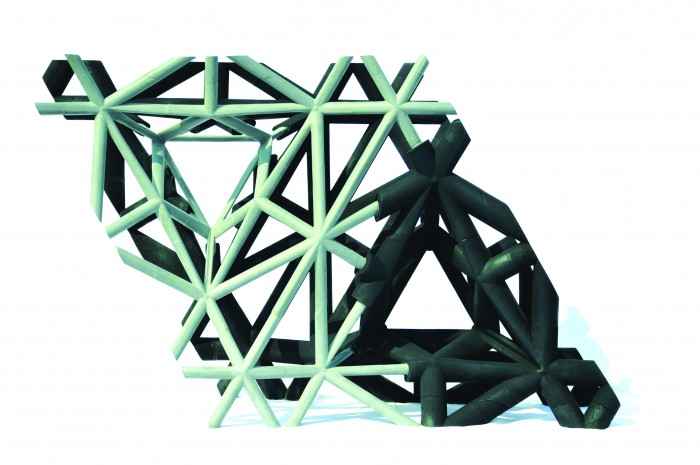

First prototype of a space frame entirely made of UHPFC (here DUCTAL® Lafarge), whose thin sections are inspired by steel construction rather than by the traditional concrete constructive models. STUDIES IN RECURSIVE LATTICES ©EZCT Architecture & Design Research, 2013

1 Guy Debord, Considérations sur l’assassinat de Gérard Lebovici, Editions Gérard Lebovici, Paris. The complete quote is: “But, like the proletariat, I am not supposed to be in the world. Thus Gérard Lebovici is immediately suspected of having dangerous commerce with ghosts. The defeat of rational thought, so obvious and so deliberately sought in the spectacle, causes any practice outside the official magic organised by the State or the omnipresent mirror of the world where everything is presented the wrong way round, to be vilified as black magic, or collaboration with the obscure forces of the gurus, the Voodoo and so on. Saying that two and two make four is becoming a revolutionary act. Dare we, in France, think outside the frame? NO – terrorism! The outside is wrong, and the frame – built by the government – is right”.

2 F. Nietzsche, Last Letters, Winter 1887-Winter 1889, Editions Manucius. The complete passage of the letter is: “Dear friend, forgive me for speaking again: this could be the last time. I have gradually eliminated all my human relationships, out of disgust for the fact that people take me for something other than who I am. Now, it is your turn. I have been sending you my books for years so that you will one day declare honestly and naïvely ‘I abhor every word’. And you would have the right to, for you are idealistic, and I treat idealism as insincerity that has become instinct, like non-wishing to see the truth at all costs: each sentence in my books contains contempt for idealism. No fatality is more harmful than this intellectual unhealthiness that has hung over humanity as it has existed hitherto; we have devalued all reality so as to invent dishonestly an ‘ideal world’…”

3 We should remember the refusals of Gilles Deleuze, Thomas Pynchon or Guy Debord to appear on TV, especially in political or cultural programmes.

4 “[…] Here we see that solipsism, rigorously developed, coincides with pure realism. The Ego of solipsism is reduced to a point without extension, and it remains the reality that coordinates with it”. L. Wittgenstein, quoted by Ralph Rumney, in. Le Consul.

5 Mustapha Khayati, De la misère en milieu étudiant considérée sous ses aspects économique, politique, psychologique, sexuel et notamment intellectuel et de quelques moyens pour y remédier, by Members of the Situationist International Congress and the students of Strasbourg, 1967. § “Create at last the situation that makes any return to the past impossible”.

6 Karl Marx, German Ideology.

7 In. Empire, quoted by A. Jappe and R. Kurz, Les habits neufs de l’Empire. Remarques sur Negri, Hardt et Rufin, Editions Léo Scheer, 2003.

8 In his preface to Alfred Sohn-Rethel : la pensée-marchandise, Editions du croquant, 2010, Anselm Jappe recalls that Sohn- Rethel, whose critical project paralleling that of Adorno was a “criticism of money”, confronted the taboo represented by this criticism. Thus he writes that Sohn-Rethel, refusing the abstraction of the categories of understanding out of their context “brings us back to the blind action of what has governed societies over the past two thousand five hundred years: money. And this criticism of money is still as taboo today as it was in the German universities in the time of Husserl and Heidegger”.

9The complete quote is: “from now on, all the sciences, all the liberal arts, the sacred training of minds, have collapsed because they have become servile: law, the religious sciences, knowledge of nature, moral principles and the other remarkable fields where the thought of free men is bartered. Ah, what a terrible crime! We see pathetic creatures flocking to sell off literature, and men, what am I saying?- innumerable beasts- made for servile tasks, emerging from the countryside and the woods, even from the mud and filth, leaving their holes and rushing like a pack of dogs to sell and profane literature. What a disaster for culture! People who should have dug and raked have the incredible impudence to touch letters and books! And those whose job it was to guard over the livestock and clean the stables peremptorily discuss human fortune; those who should have whipped the flanks of the animals are now holding the sceptre and sitting among the magistrates; and finally, for people that differ from animals only by appearance and the place they claim, not by their attitudes, a thin icing of culture is enough for them to advance in the world with the audacity, as the poet says, of a pack of wolves […] is it thus that you, the nurse of letters, O philosophy, provide and submit to the desires of the lowest and most abject individuals?”. L. B. Alberti, Avantages et inconvénients des lettres, trad. fr. Christophe Carraud, Rebecca Lenoir, Editions Jérôme Millon, 2004.

10 In. Discours sur les sciences and les arts, 1750.

11 Ibid.

12 In. Préface au discours sur l’origine et les fondements de l’inégalité parmi les hommes, 1755.

13 We know how much this movement influenced Arts & Crafts.

14 Charles Babbage, Preface to The Economy of Machinery and Manufactures, Charles Knight, 1832, p. V. “Those who possess rank in a manufacturing country, can scarcely be excused if they are entirely ignorant of principles, whose development has produced its greatness”.

15 “The law of accelerating returns is fundamentally an economic theory. Contemporary economic theory and policy are based on outdated models that emphasize energy costs, commodity prices, and capital investment in plant and equipment as key driving factors, while largely overlooking computational capacity, memory, bandwidth, the size of technology, intellectual property, knowledge, and other increasingly (and increasingly increasing) constituents that are driving the economy”, in. Ray Kurzweil, The Singularity is Near, Viking, NY, 2005.

16 Marie-José Durand-Richard notes that “the chapters on ‘division of work and manufacture’ and ‘machinism and large scale industry’ in Capital are based on Babbage’s analysis” in. Marie-José Durand-Richard, « Le regard français de Charles Babbage (1791-1971) on the ‘Decline of Science in England’ », in Documents pour l’histoire et les techniques, n° 19 (2nd quarter 2010), Les techniques et la technologie entre la France et la Grande-Bretagne XVIIe-XIXe siècles.

17 Anselm Jappe and Robert Kurz, Les habits neufs de l’Empire. Remarques sur Negri, Hardt et Rufin, Editions Léo Scheer, 2003.

18 “Singularity is not about faith, it is about understanding”, Ray Kurzweil.

19 Mustapha khayati, De la misère en milieu étudiant, considérée sous ses aspects économiques, politique, psychologique, sexuel et notamment intellectuel et de quelque moyens d’y remédier, by Members of the Internationale Situationniste and students from Strasbourg, 1967. § “Finally create the situation that makes it impossible to return to the past”.

20 Mohamed Dahou, Guy Ernest Debord, Potlatch n°21, 30 juin 1955.

21 O. Spengler, Man and Technique, 1933. French tr. by Editions Gallimard, Paris, 1958.

22 “The layman reading Spengler as he had done previously for Nietzsche and Schopenhauer, had become meanwhile a stranger to philosophy; the professional philosophers stuck to Heidegger, who gave a more successful, interesting expression to their depression. It ennobled the death decreed by Spengler with no consideration for the person, and promised to transform thought on death into a mystery that must be administered by the academic. Spengler was no longer a participant: his brochure on Man and Technique no longer competed with his day’s cleverly expressed anthropology. His relations with the National Socialists, his quarrel with Hitler and his death all went unnoticed […]”.Theodor W. Adorno, in. Prismes, Payot, 1986. Here it should be noted that Adorno had enough intelligence to limit his own “cultural pessimism”, something that Heidegger’s philosophy preferred to forget. That defect is today a proudly exhibited certificate of authenticity brandished by all professional pessimists: “Cultural pessimism did not die with Fascism. On the contrary, it is only today that, in the form of ontologic fundamentalism and criticism of science and civilisation, that it has gained greater plausibility, given the undeniable importance of its old criticism of the destruction of life’s natural foundations. It has always transformed this criticism into ontology, on the ground that ‘a natural world order’ had to be preserved, with all the reactionary features typical of this thought”. Robert Kurz, in. L’honneur perdu du travail. Le socialisme des producteurs comme impossibilité logique.

23 Cf. Philippe Morel, The Integral Capitalism (from the Master’s Thesis Living in the Ice Age, 2000-2002). English translation, with a new introduction, published by Haecceity, Quarterly Architecture Essay (QAE), Volume 2/Issue 2, Winter 2007. Available at www.haecceityinc.com. The concept of cognitive capitalism barely touches on the nature of today’s capitalism and its dependence upon computing power and the global technological infrastructure. Thus it ignores “robot trading” or algorithmic trading against which it is theoretically powerless, and many other phenomena.

24 Many fashionable instances of this idealism may be found at http://thefunambulist.net/

25 “A further reason why industrial society cannot be reformed […] is that modern technology is a unified system in which all parts are dependent on one another. You can’t get rid of the ‘bad’ parts of technology and retain only the ‘good’ parts. Take modern medicine, for example. Progress in medical science depends on progress in chemistry, physics, biology, computer science and other fields”. Theodore Kaczynski, The Unabomber’s Manifesto, quoted by Ray Kurzweil.

26 F. Nietzsche, Rough copy of a Letter to Georg Brandes, December 1888, in. Last Letters, Winter 1887-Winter 1889, Editions Manucius, p. 192.

27 Gracchus Babeuf, Le tribun du peuple, n°40, février 1796, in. Babeuf, Textes choisis, Editions sociales.

28 Gracchus Babeuf, Le cadastre perpétuel, 1789, in. Babeuf, Textes choisis, Editions sociales, p. 97.

29 Ibid.

30 “Socrates and Plato, great doubters and admirable innovators were nevertheless incredibly naive in regard to that fatal prejudice, that profound error which maintains that ‘the right knowledge must necessarily be followed by the right action’. In holding this principle they were still the heirs of the universal folly and presumption that knowledge exists concerning the essence of an action. “It would be dreadful if the comprehension of the essence of a right action were not followed by that right action itself” — this was the only outcome considered by these great men – the contrary seemed to them to be crazy and inconceivable – and yet the contrary position is in fact the naked reality which has been demonstrated daily and hourly from time immemorial.”

31 Asger Jorn, Image et Forme, extract published in Potlatch n°15, 22 December 1954. The full quote is “We must arrive at a dynamic conception of forms; we must face up to the truth that all human form is in a state of continual transformation. We must not, like the rationalists, avoid this transformation; the failure of the rationalists is in not understanding that the only way to avoid the anarchy of change is to become aware of the laws by which this transformation is operated, and use them […].”

32 Ibid.

33 Anselm Jappe, in. Politique sans politique.

34 F. Nietzsche, Rough draft of “Letter To the Emperor William II”, December 1888. In. Last Letters, Winter 1887-Winter 1889, Editions Manucius.

35 Anselm Jappe, Ibid.

36 Marshall McLuhan, Mutations 1990, Tr. Fr. Editions Mame.

37 Vladimir Mayakovski published this work in 1926. The passages on the telephone that transforms the whole world into a village in which each person can, as if in the main square, talk about the weather although they are thousands of kilometres away from each other, is a forerunner of McLuhan’s analyses.

38 McLuhan fell into this trap, but most of his speculative hypotheses remain valid. Cf. Sidney Finkelstein, Sense and Nonsense of McLuhan, International Publishers Co., Inc., New York, 1968.

39 Cf. Ph. Morel, L’Architecture au-delà des formes : le tournant computationnel (Architecture beyond Form: The Computational Turn), exhibition, Marseille, 2007.

40 Karl Marx, Manuscripts from 1844, tr. Fr. Emile Bottigelli, Paris, Editions sociales, 1972, p. 130. Quoted by par Anselm Jappe, in Alfred Sohn-Rethel : la pensée-marchandise, Editions du croquant, 2010.

41 Alfred Sohn-Rethel : la pensée-marchandise, Editions du croquant, 2010. Preface by Anselm Jappe.

42 Cf. George Thomson, The First Philosophers, Lawrence & Wishart, London, 1955.

43 Cf. the German school of “Criticism of Value” (Wertkritik) and Anselm Jappe, Les aventures de la marchandise. Pour une nouvelle critique de la valeur, Denoël, Paris, 2003.

44 Gertrude Stein, “Counting is the religion of our generation, its hope and salvation”.

45 Robert Kurz, L’honneur perdu du travail. Le socialisme des producteurs comme impossibilité logique.

46 I. S. n°6, Août 1961, p. 11.

47 Claude Mazauric, introduction to Babeuf, Textes choisis, Editions sociales.

48 Gracchus Babeuf, quoted by Claude Mazauric, in. Babeuf, Textes choisis, Editions sociales.

49 Rousseau, In. Discours sur l’origine et les fondements de l’inégalité parmi les hommes, Part II, 1755.