Come Maiz Monsanto

Keywords: art museums, beadwork, breeders, code, color combination, copyright, corn, Cuzco, database, DNA, Eduardo Villanes, farmers, field, GMO, government, intellectual property, loom, maize, Microtextiles, Monsanto, multinational, natural resources, Peru, Peruvian, Plants, precolombian, rural, seeds, textile, transgenic

Can corn be classified as 'intellectual property'?

Come Maíz Monsanto

Corn as intellectual property.

By Eduardo Villanes

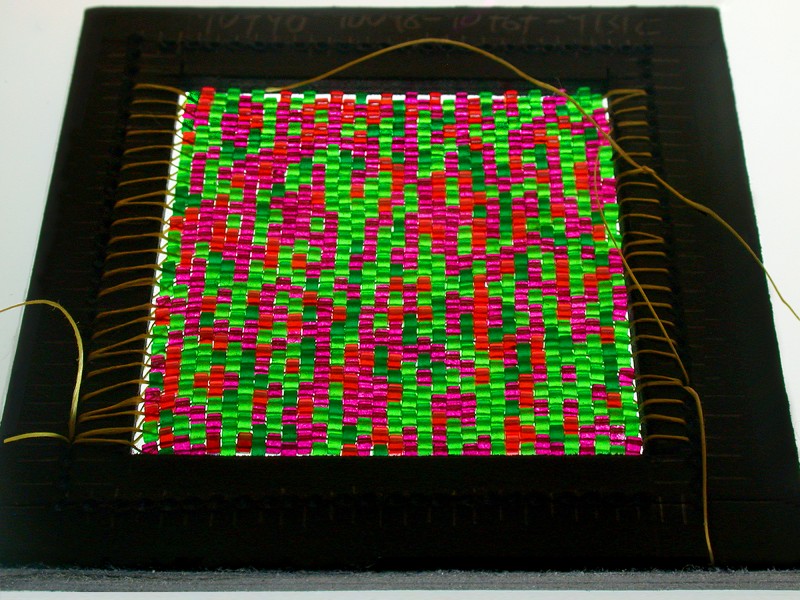

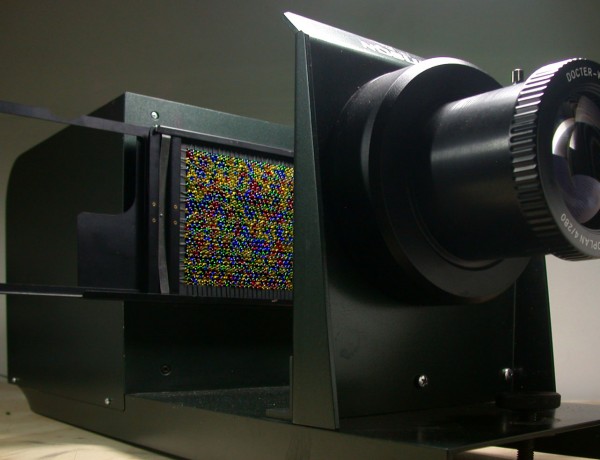

Microtextiles are miniature translucent beadworks loomed within tiny cardboard frames. Their color combination is the visual representation of corn DNA: 4 colors representing 4 bases. They function as photo slides and can be projected using slide projectors or visualized on light tables.

Microtextiles refer to precolumbian Peruvian textiles that carry encoded information: ancient databases were made of textile.“Microtextiles” make a relation between those textiles and corn, also a cultural legacy but relegated to oblivion by Peruvian cultural policy.

The variations in Microtextiles’ hues attest to maize’s biodiversity, which is expressed in impressive arrays of color. Perú was one of the centers of biodiversification of maize, the result of skillful work on behalf of countless generations of breeders. Because of its beauty and the craft involved in its making, it is considered a work of art, just as Peruvian ancient textile is.

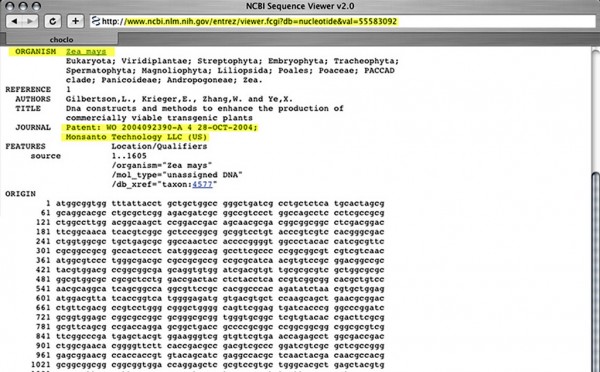

Corn is the target for multinational corporative interests. Its DNA has been decoded and patented by Monsanto, becoming its “intellectual property.” Transcribing DNA “copyrighted” by a corporation into textiles reminds us who really made possible what we have today in corn and other plants: the breeders who were themselves artists of an important sort.

Native farmers are subject to violent repression and their voice is silenced by the media for opposing the destruction of natural resources like crops and water. Although farmers wear textiles similar to those displayed in museums and have been the seed keepers of corn for many generations, neither people nor corn have a place in art museums in Perú. It seems that living beings can’t be accepted by the cultural establishment.

In 2007, Monsanto lobbied the Peruvian government in order to introduce GMO crops in Peru. At that time I was living in a rural area in the US which allowed me to imagine what the consequences in Peru might be. The agricultural catastrophe I was witnessing would be of greater magnitude in my country because we have a rich biodiversity of corn that could go extinct.

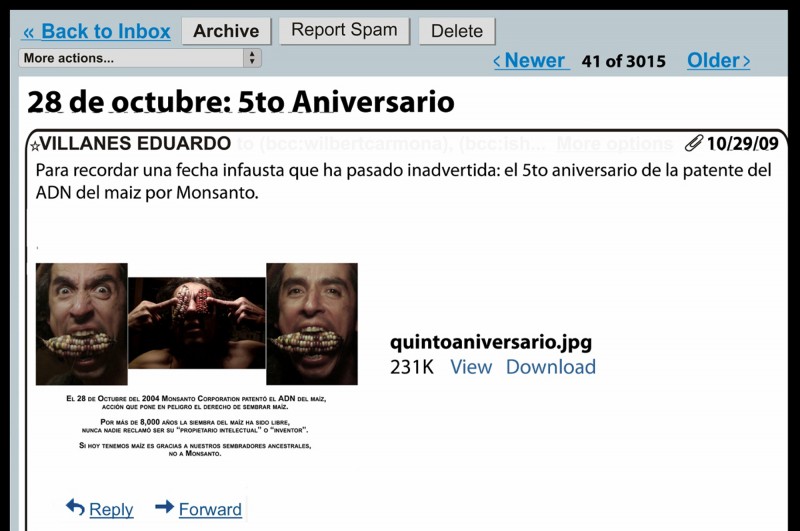

During that year the introduction of GMO seeds could have happened any day so the public needed to know about this approaching danger as quickly as possible. I emailed authorities in charge of the most visited art museum in Lima –MALI- to explain the situation and to request its façade to exhibit art against GMOs. They seemed not to understand me so I resorted to explaining it in a simpler way: a photo of a corn field near my town and the paragraph below.

July 12, 2007

Subject: Transgenic Corn Field

I share with you this photo that I took in a transgenic corn field in Massachusetts. The sign is a requirement from the seed company, it alerts that it is “prohibited” to take seeds away to plant them in another field because those seeds are somebody’s “intellectual property”. Can you imagine the shame of having those signs in our land? Maybe in Cuzco?

I realized that emails like that could work for my purpose, so I forwarded it to my contacts in Perú and it went viral. That is how I started my email campaign that lasted many years, which included text, images and sabotaged videos from monsanto.com

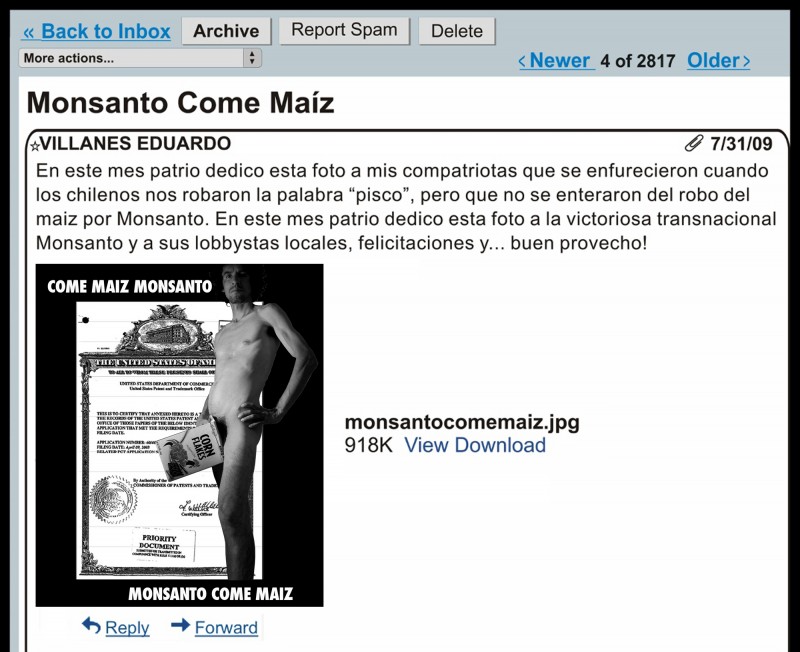

The email “Monsanto Come Maíz” shows me posing with a Kellogg’s corn flakes box as a codpiece. The background image is the application form -from the US Patent and Trademark Office- filled by Monsanto to request the patent of corn DNA in 2004. The last paragraph of the email reads: I dedicate this photo to Monsanto and its lobbyist in Peruvian government, congratulations and…bon apétit!

In 2011 my exhibition of Microtextiles was censored in Perú by a multinational corporation, Telefónica of Spain, an influential patronage for the arts. As an Inquisition Tribunal they decide, with the servile consent of the local intelligentsia, what has to be censored. As a response I have been doing clandestine interventions in the city, which included graffitiing the façade of MALI and pasting in streets silkscreen prints of my microtextiles.

More about Monsanto

More about Eduardo Villanes