Decrophilia

Keywords: ada o'higgins, decrophilia, matt raviotta, Matthew Raviotta

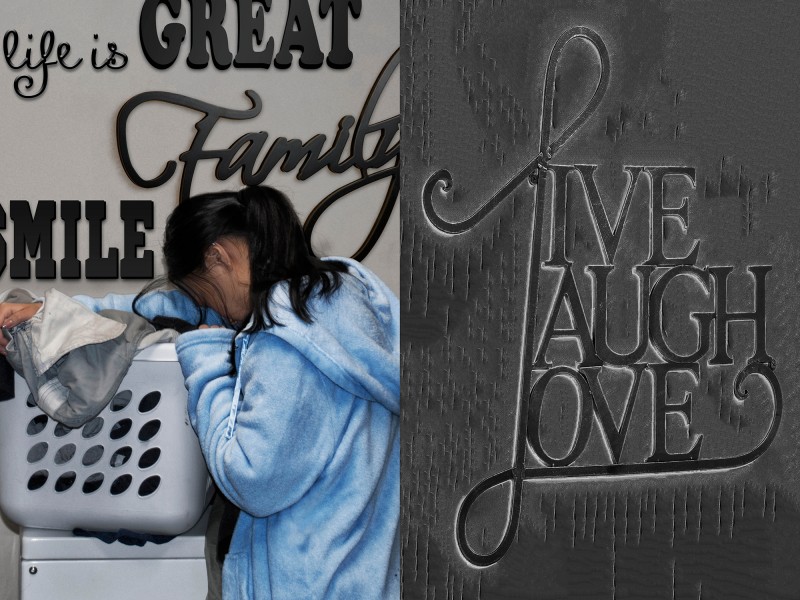

Matthew Raviotta explores the aesthetics of suburban comfort

Courtesy the artist and Badlands Unlimited

DECROPHILIA, out now on Badlands Unlimited by artist Matthew Raviotta stylishly excavates the exotic and familiar world of American suburbia. In a sequence of seductive and sometimes bewildering images, the book mines the trappings of comfort that epitomize the mythic “good life” of middle class incomes and stable homes. Compositions with scented candles, custom shower curtains, and cough medicine juxtapose with writhing bodies and models that embody the look and feel of “flu chic.” Contrast between the longing of subconscious desire outside the bounds of comfort and the charmingly demented reality of suburban life are brought into sharp and hilarious relief.

Ada O’Higgins: What is your experience of suburbia?

Matthew Raviotta: I think my attraction to suburban aesthetics stems from my personal experience. I grew up in a suburb outside of New Orleans before moving to New York City after college. By now, enough time has passed for me to feel nostalgic about the time I spent in the suburbs and what those years ultimately represent. Decrophilia is my attempt to explore the mythical intersection between familiarity and foreignness, near and far, memory and fantasy.

AO: What does Decrophilia mean?

MR: It’s a dark play on the word ‘necrophilia,’ combined with the words decor and philia (ancient greek for love). I wanted to allude to a clinical obsession or love affair with decorative aesthetics, that could be characterized as a morbid or erotic fixation (or both).

AO: I know Youtube is a huge inspiration for you, how did the platform play into your process?

MR: Youtube is, without a doubt, my favorite online platform which, in my research, provided an invaluable window into the lives of many suburbanites. It’s a fascinating place. Because it’s so self aggregating, it has enabled many different communities to flourish in ways they would never be able to offline. In a way, it mirrors the suburban community model in that it’s a form of connected isolationism.

AO: Tell us about your long love affair with Yankee Candles.

MR: I got into Yankee Candle almost two years ago because of a viral Youtube video called I MIGHT Boycott Bath & Body Works RANT!. This woman (Az4Angela in case you aren’t familiar) made a video about her harrowing experience trying to buy two specific three-wick candles (Winter Candy Apple & Iced Gingerbread) from Bath & Body works. I soon moved onto her other videos, most of which were candle reviews, weekend vlogs, Oreo taste tests, wax hauls, dollar tree hauls, or guinea pig care advice. Before long, I was making my own trips to Yankee, Bath & Bodyworks, and anywhere else that sells candles. I’ve amassed quite a collection.

Candles and candle culture are fascinating to me because they rely on the marketing of an abstract idea. Candles take a place or a feeling (Mountain Lodge, Drift Away, Afternoon, Sun & Sand) and represent it as both an image and a scent captured in a jar. What does Afternoon smell like? What does it feel like and what does it mean? Whether the consumer is aware of it or not, these candles are examining our feelings, moods, and the depths of our cultural psyche. Even the candles’ graphic labels are an interesting exercise in semiotics. What does a Summer Wish look like? What is the most appealing visual manifestation of Pink Sands? How do you sell a Midsummer’s Night?

AO: Comfort is a theme of Decrophilia: it’s desirability, function, and commodification in American consumerist culture. What is the significance of the concept of comfort in relation to American identity and the individual psyches of millennials such as yourself?

MR: I think that comfort, in all of it’s forms and manifestations, is one of the most important American ideals. People want to live comfortably and die comfortably. Comfort is a luxury that people aspire to. It drives our economy and feeds so many industries. People equate physical comfort with success. The notion of comfort and the idea of suburbia are inextricable because of what the suburbs symbolize. Since their inception, the suburbs have been an escape from the rough grit of the city; they are padded and protected pockets of life. In the suburbs you are insulated from the hardships and violence of urban living. This can also mean being protected from a certain social and self consciousness that comes with being confronted with city life. For our parents and grandparents, the suburbs were the American dream. I think that idea was still pervasive when I was growing up in the suburbs, but in the reality of it translated into feelings of comfort and complacency. As an emotionally and physically immature and dependent teen, I experienced this insulation in a very magnified way—it was a feeling comparable to submission. The suburbs provided me with a perfectly digestible and non-threatening dose of reality.

AO: The Chapter ‘I <3 being Sick’ really stands out to me as a visual statement. Being mildly sick seems like a comforting refuge from the soulless, alienating workplace of today. Has it come to the point where being sick enough to stay in the comfort of our own homes is more desirable than going outside and facing the meaninglessness of contemporary existence?

MR: Sickness can feel like an escape. Historically, the idea of sickness has always been romanticized. Everyone gets sick, but not everyone can be sick. Not everyone can afford to embody the iconic state of sickness. Being sick is a status symbol that says “I can be weak and helpless and taken care of.” Tuberculosis, widely known as Consumption, ravaged the 18th and 19th centuries. At the same time it became a widely aestheticized fashion trend, defining notions of feminine beauty that still exist today: thinness, gauntness, paleness, and apathy. Aside from being romanticized, the state of sickness has also been commodified into a world of practical––if sometimes superfluous––accessories that make being mildly unwell even more desirable. No longer does one have to worry about their cold compress not matching their pajamas. Tissue boxes become decorative focal points and are no longer hidden in the home. Even a thermometer can be cute. The accessibility and pervasiveness of Social Media has taken sickness a step further, allowing literally anyone to put on and partake in the performance. It’s très #fluchic.

AO: ‘Anywhere But Here’: there is a tension between an appreciation for domestic coziness and a certain disgust for this false constructed sense of selfhood and comfort. How do you navigate this tension personally and how do you see it being navigated by those around you?

MR: ‘Anywhere But Here’ is, to me, the manifestation of a deep desire to escape. This wanderlust manifests itself in the accumulation of decor that masks the reality of the home. As inauthentic as a wall plastered with faux-aged shutters and French cheese and Eiffel Tower picture frames may seem, I see these ephemera as an honest expression of the inner entrapment and despair that can emerge out of a domestic space.

AO: The suburban middle class obsession with ‘cleanliness’ is touched upon in your book. What do you see as the roots of this obsession which is often coupled with a fear of dirt and disorder. I myself see it as a fear of the chaos within, a way of controlling one’s emotions by controlling their environment as best they can.

MR: I think it absolutely is a fear of chaos. To keep a clean home is a sort of outwardly testament to one’s sanity. The idea is that, if you aren’t plagued by inner demons, depression, suicidal thoughts, marital strife, unemployment, and bankruptcy, you can spend your time doing other things like polishing and upkeeping your home. The home is an extension of the self; the illusion of outward upkeep perpetuates the illusion of inner upkeep. I think cleanliness is also rooted in the idea of conformity and acceptance. To live in an unclean home is to step outside the boundaries of what is normal and acceptable to the community and society at large. An unclean home invites judgement and ostracism. The fear of these consequences fuels an obsession that borders on neurosis.

AO: Where does your interest in generic global suburban aesthetics come from? Do you think this aesthetic is taking over and giving less of a voice to other, perhaps more niche aesthetics, or is it over-saturating people to the point where they more willingly turn to other aesthetics?

MR: What’s most interesting to me about this aesthetic is that it’s a removed state of existence from the traditional canon of art & design. It’s a bastardized hybrid of several different aesthetics. It’s a Cape Cod beach house in Iowa. It’s a Modern Colonial Revival in California. It’s a French Vineyard in Arkansas. When you strip these things of their traditional signifiers and environment, and mix in things that have no contextual connection you create a sort of aesthetic monstrosity that doesn’t belong anywhere. I’m opposed to the idea of dismissing taste and design as good, bad, wrong, or right. Instead, I’d prefer to play the role of objective observer. In this sense,I think that this suburban aesthetic mutation is an interesting phenomenon in its almost radical dismissal of “the rules’ of good taste.

AO: What’s the future of Decrophilia?

MR: I’m seeing a whole line of Decrophilia HOME products: bath and kitchen mats, key hangers, candy dishes, custom scented candles and room sprays.