The work continues

Keywords: Election Renewal, hannah black, mariame kaba

Hannah Black and Mariame Kaba discuss this election season, feminism, activism and the future

I encountered Mariame Kaba’s work through her Twitter and her blog, Prison Culture. She is an organizer, educator and curator, based in Chicago for over 20 years and now back in her hometown of New York. I interviewed Mariame over the phone.

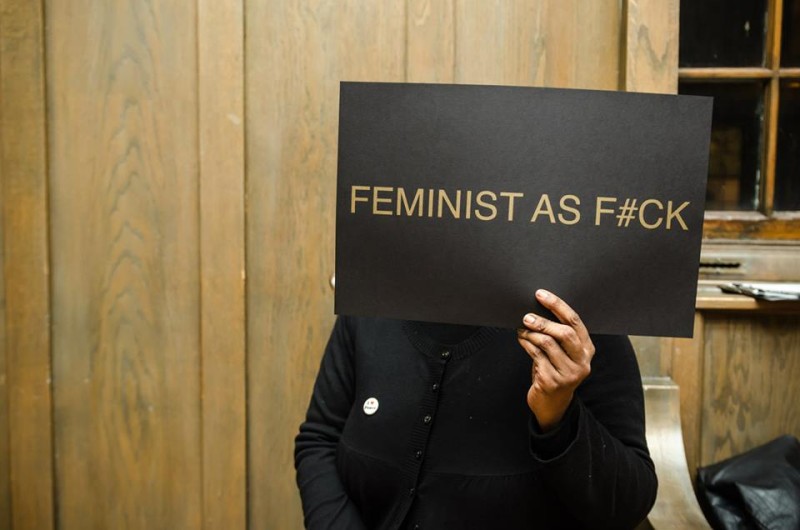

Image courtesy Mariame Kaba

Though Mariame came to mind for this issue of the magazine because I loved her election commentary on Twitter, her real work is as an organizer and educator: she focuses on ending violence, dismantling the prison industrial complex, transformative justice and supporting youth leadership development. Elections happen every few years, but courts, police and social services in the USA enact daily brutalities, from the mundane to the spectacular, and incarceration, impoverishment and violence are daily realities of society. So, too, are organizers like Mariame, mustering and channeling the collective strength of their communities.

Her perspective on the election as a family argument between white people that has seized on Donald Trump as a monstrous figure in order to avoid a deeper conversation about endemic racism (especially anti-blackness) and misogyny seems fully correct to me. The media likes to insist that the apocalypse is coming tomorrow, instead of already here, already happened, we’re already working on dealing with that.

As Mariame points out toward the end of this interview, long-game political goals are means of structuring what we do now. Our goals assist us in distinguishing between what helps and what hinders. Our collective goal has to be the end of capitalism, a monster that grew fat on slavery and the colony and continues to live off suffering.

To put the nature of that work very simply, I could say we have to put our energies toward each other, but to get involved in that easy “each other” we also have to understand who we are, and be real about what we have benefitted from, where we are coming from, and where we want to go. I find Mariame’s experience and wisdom really helpful in thinking about all of this.

Hannah Black: So the first question is, you’ve mentioned how as a Black American woman you don’t see Trump as an extraordinary new phenomenon and that his politics seem to you to be consistent with your overall experience of white America. So I just wanted to ask you to expand on this point. It feels important as Trump has been described as if he were an unexpected novelty, which does little to explain his success.

Mariame Kaba: OK, yeah, sure. My thoughts are that mainly people have tried very hard to exceptionalize Trump as though he’s some figure that Americans are unfamiliar with, and I just have found that to be incredibly disingenuous. You could look at demagogues of the past in our country, George Wallace, for example, people who seem to come up and try to capture the popular sentiment, particularly a white nationalist sentiment in the country in order to be able to pursue their goals for attaining power. So I find it interesting that there’s such an attempt to make Trump so incredibly singular rather than to connect him to the broader history of the country.

HB: I think that’s an important point because how white nationalism is often talked about is as if it would usually be in the way of someone becoming powerful.

MK: Obviously in this country, a country that’s built on racism and built on genocide and built on the exploitation of certain classes of people, I don’t understand why people are taken aback or feel that this is a shocking moment in some way. It’s just within the genealogy of what always has been. I think if you understand it that way then you can’t make Trump into some sort of monster. I think that’s not helpful to people. People very much like to create monsters, and that’s a way to scare other people into complying, into not using their brains, not being critical thinkers, making sure that power continues to consolidate itself in one direction, toward the powerful. I think that’s a big part of it, to be honest.

HB: The next question is about Trump’s base. I wondered if you had any observations about who has fuelled his rise and how that’s going to continue after the election. I was particularly interested in your comments online after the successful shutdown of the Trump rally in Chicago. I remember you said something about how — given what you’re saying about Trump being part of a long history of white supremacy, you made a point about how at the Trump rally there were unusually violent expressions of racism that did feel new to you —

MK:It’s not that it was new, it was that in Chicago people hadn’t come out and been openly racist in the way they were at that rally, but that’s a concentrated space. I don’t think that’s important. The question of who is Trump’s base seems to be the only question that matters [to the media]. It speaks to the point that I made before that this entire election is a conversation between white people about whiteness in the service of figuring out what to do with everybody else. That plays itself out in the ways that coverage and media has been focused almost exclusively on who are the people who support Trump, as though we need to dissect and go into an anthropology dissertation because they’re so strange. This is a family argument that’s going on between white people. We are on the outside of that. We are being talked about, of course. We are centred in [the questions of] who needs to go, who needs to be excluded, who needs to be destroyed, but our actual thoughts and feelings aren’t part of this conversation at all. So of course it makes sense that other white people are really interested in the intricate details and more importantly the interiority of who his supporters are, in order to make them more human, right? To humanize them to each other.

[From white people’s point of view] these are not people who are separate from us, these are our cousins, we desperately want to understand what they’re doing and what they’re thinking and who they are, and we have so much empathy for them, because we’ve now basically scapegoated white working class people and said that they are the ones who are driving this whole entire populism and white nationalism and Trump’s candidacy when empirical data keeps showing that white Trump supporters have higher median incomes than white Clinton supporters. So, the people who are supporting Trump are the people who have always supported the GOP — mostly people who are one rung ahead of working class people, the middle manager class of people, they don’t necessarily have college degrees but they have income that is sufficient enough for them to not be poor. Those are the people who are supporting him because those are the people who support the Republicans in general.

Constantly talking about [Trump’s popularity] as though it’s some exceptional thing, like an alien landing into the country from outer space, is nuts. These people are the people who support the GOP in general; they’re just supporting Trump because they agree with him. The things that have not been said out loud in the GOP for years have just been put on blast this year in a way that the establishment white GOP are unhappy with because they love to trade in dog-whistles, and Trump uses a megaphone, and yells things very loudly, and that’s very upsetting, unsettling and anger-making for the people who like to work in the boardrooms and call themselves Republicans and members of the GOP. There’s a polite group of people who use euphemistic language to say the same things that the base just says incredibly loudly.

It all goes back to the root of trying to make him an exceptional figure, and then all the data not supporting that. To be very honest with you, I don’t care how his supporters are rationalizing their support of him as long as he continues to espouse openly racist, xenophobic, Islamophobic, misogynistic ideas as well as offering policies that would continue to solidify those things, I don’t care why they’re supporting him, I only care that they’re supporting this racist person, this misogynist, because that has a direct impact on me and my ability to live in the world. I care about the material and real-world consequences of their rhetoric and policies.

HB: I’m from the UK and I don’t know if you’ve followed anything around the Brexit stuff, but it’s been completely identical: this idea that it’s a white working class thing—also that the working class is white, which, maybe it’s harder to make that fantasy in America, but it’s a very strong fantasy in Britain: the fantasy that the working class is all white people, and they’re the ones that voted for these nationalists. And then all the demographic data suggests that that’s not true, like you’re saying. It’s a weird thing where my empathy is demanded toward people who I don’t think are in an empathetic relation to people of color.

MK: Well, you know, it’s normal within white supremacy. The people who are allowed to have feelings are white people. The people who are allowed to be complicated and complex people are white people. So, we’re very interested—and I don’t mean me, meaning myself, I mean in general, the culture is very interested in centering white people. The interest is in their stories and talking about their emotions, figuring out how they feel. That’s the frame from which everything else radiates. So I guess, for me, it makes complete sense that every single day there’s some deeply reported piece somewhere about this particular population and yet, you don’t see the same thing at all on Clinton’s end. You don’t see big exposés about who’s supporting Clinton and why. And more importantly you don’t have pieces humanizing those people. And guess who the working class is filled with in this country? Black and brown people. They’re in big numbers amongst the working class. But no, our interest is not in the working class, it’s in the white working class. Again, there’s the importance in understanding that this election is actually about whiteness and a family argument among white people. Once you get that, everything begins to make sense.

HB: I wondered if you think that Black Lives Matter’s visibility as a slogan and as an array of practices has been, in any way, useful in ameliorating or reframing the discussion around structural anti-blackness.

MK:It’s a movement that is a long-standing one, and that has its most recent iteration in the Black Lives Matter formations. On the GOP side, there’s a militant use and deployment of Black Lives Matter as “All Lives Matter” and the ability to again intentionally and violently suppress blackness. Because blackness is so fungible according to white supremacy, we’re not even allowed to use that terminology—everyone must be included. So, it’s a violent flattening of everything in order to erase the particular aspects of anti-blackness and anti-Black racism. So, you’ve seen that happening—the whole [GOP] convention was a bunch of people coming out and denouncing Black Lives Matter as a terrorist organization. [It’s the same] way that the right has always used and deployed and blackness—weaponizing blackness to justify the violent repression and putting-down of Black people that continues to this day. From one side of things, when you see BLM being used in this kind of way, being weaponized by the right, that is not shocking.

On the side of the Democratic centrist party, you’ve got BLM playing an interesting role there too. You’ve got, on the one hand, the democratic-socialist Bernie Sanders who’s confronted very openly in Seattle [by BLM activists including Marissa Johnson and Mara Willaford] and people are apoplectic. “We care about Black people, why are these people coming at us, why aren’t they coming at Hillary Clinton, we care about race!” Well, you know, Bernie Sanders didn’t have a racial justice platform before those confrontations. He didn’t hire his press secretary, Symone Sanders, a Black woman, until after those confrontations. So, those confrontations that those BLM Seattle and other people led, actually got what they wanted, which was a hearing around the issues they cared about.

Now, did [Bernie Sanders] talk about those issues perfectly? No, because this was new to him, and new to his campaign. But his racial justice focus was infinitely better because of the confrontation that those young people brought to his doorstep and basically pushed and forced them onto his agenda. So that was one part of it. In terms of Clinton, she’s done what the Clintons always do, which is to appropriate language and rhetoric and promise vague policies that aren’t going to really make a profound difference. They’ve met with people in closed-door meetings. They’ve used terms like “intersectionality” and [given] speeches in Harlem. They’ve done all of the patina, the surface level stuff that you do to kind of give a head nod that you get it. But I don’t think anything that’s been offered by that campaign is going to markedly transform the lives of millions and millions of Black people who desperately need their lives transformed, in terms of having their material needs met in order for them to be able to live lives of dignity without having to struggle constantly to be able to make ends meet.

I think it’s early for this iteration of the movement of Black Lives. It’s early to figure out what it all means, it’s early to figure out how it will morph and transform post-election. It’s been very interesting to me to watch how different factions have responded to this issue of elections. There has been the BLM network very clearly not endorsing a candidate. Some of the Campaign Zero people have made individual endorsements of Clinton. They’ve been more Clinton-friendly. They’ve met with Bernie Sanders too, but many of their members have been more vocal about the importance of voting, and of voting against Trump. So I think it’s a huge tent. Understanding the movement of Black Lives in this moment is understanding that it’s not one thing. When people talk about BLM and they kind of focus in on just one small thing, that’s kind of an insult to the multitude of organizations and individuals who are organizing underneath a large umbrella of what they see as a struggle for Black Liberation. It’s more of a mark of how little people know about what’s actually going on; how ignorant people are about what is actually happening on the ground. And that’s because it’s a decentralized movement. It’s not a movement that has one main leader, who is charismatic, who everyone can interview every single day about everything on the planet. That leader would usually be a cis Black male. They’ve tried to do that in various ways for other people but it just hasn’t worked because that’s not how this actual movement has been evolving. It has been decentralized; it has various points of leadership led by different kinds of people.

HB: I’m interested in you situating the spectacle of the election in this longer struggle. I wonder what kind of successes in your own work as an activist, or however you think of or describe that work, and what makes this work possible in what can often feel like a bleak, sad set of circumstances. I also wonder if you felt that maybe one of the problems of getting hung up on an election is that this kind of work has to be local and community based and doesn’t work on this sort of abstract level.

MK:Most of us who are organizers in whatever area, or focus, or issue you are particularly focused on, we work all of the time, whether there is an election or not. The work continues. I think a smart organizer will definitely pay attention to elections on both the local or state or, on the national level, to figure out if there are pressure points and openings that exist to be able to move your issue. You’re not going to ignore that. Politics are politics, and that means that electoral politics are part of the larger politics that we engage in in the world and in the country, so I definitely use elections to either figure out who I don’t want to have in office anymore, who needs to go, so it’s a measure of accountability of some sort, or it’s a way to figure out how to use the fact that there is an election to raise a certain issue. So you have to have a strategic vision and it is important to use all the tools in a tool kit if you are somebody who makes stuff, if you are somebody who tries to build a different world, if you are interested in transformation and justice, and you have to play in all arenas that exist while also pushing for people to be more expansive about what they want and what to ask for and demand from that particular system. So, yes I’ve been involved in many different campaigns over a long period of time. So, I’ve worked to close youth prisons. I’ve worked on campaigns to change the laws around juvenile expungement, so that young people who get arrested can have clear records that don’t carry over into other parts of their lives and make it difficult for them to have futures that are productive and allow them to make a living for themselves or for them to go to school, or do whatever. I’ve worked on individual campaigns to defend particular people who are criminalized for various kinds of things over many years. I’m going to continue, regardless of who the president is or who the mayor is or who the governor is.

HB: Do you see the demand for abolition of prison or police as a realistic policy change that could happen in our lifetimes or in those of our children or is it kind of an abstract goal to kind of strive towards?

MK: Abolition isn’t mainly a demand but more so it is a goal. And, more than that, it’s a vision of/for the future. The focus is not about policy, but it’s about social movement. So, I think you can craft abolitionist demands, sure, but I think abolition itself is a goal that is very much about changing everything, and it isn’t just about ending prisons and police and surveillance. You can’t abolish police, for example, without ending capitalism, how is that going to be possible? I think that you have to create the conditions that allow the end of those things that you’re trying to end. So, you’ve got to do work in the short and interim terms that move that in the direction of abolition. You can’t get caught up in what’s practical. You have to be willing to offer an intervention that says that we need to change everything.

And you have to also think about creating: what do you build up while you are tearing down and dismantling? So, the interpersonal work that people are doing is very important work, figuring out how we’re going to reshape and restructure our individual relationships with each other as human beings in order to support a larger transformation and shift that needs to happen. It’s incredibly important to figure out how you’re going to handle conflicts in your community in a way that is not focused on punishment and is still providing people with accountability and is still making sure that people get what they need in terms of feeling as though if they were hurt and harmed that these were considered and addressed. People need and want to feel safe. That’s important. It’s a fallacy to think that there won’t be violence as we are building for abolition. Of course there will be. The point is that the current systems set up to deal with various harms are themselves incredibly violent, inhumane and ineffective. So we need something else. We need a just system to evaluate and adjudicate harm. We don’t currently have that.

I think that we just have to think and imagine bigger and understand that these things take a long time and we’re not going to end things in this moment, we’re not going to rebuild the entire world in seconds, and that we’re part of a long struggle. We basically have to abolish the society that makes prisons, police and surveillance seem normal and necessary. That’s basically the situation. I don’t get too caught up in what the timeline of things are, I’m interested in questions of how to act. Ideally, to act with a goal in mind. For some people, the end goal is reform, so that is going to shape the policies, the ideas, the practices that they use in order to achieve that end goal. My end goal is abolition. That’s going to shape my demands, it’s going to shape the policies I care about and want to fight for, it’s going to shape everything. I’m going to want to ask of everything that I propose or act upon whether it is setting up barriers to my goal of abolition. Over the last decade, I’ve been trying different things out. I’ve been catalyzing small projects that serve as alternatives to the current punishment systems. I’ve been trying out various interventions. I’ve seen various successes and failures. We all need to be doing this. I’m practicing abolition every day.

HB: What are some ways people reading this can contribute to building transitional communal structures to avoid supporting the prison industrial complex?

MK: I think people should work where they are, doing the thing they are most passionate [about], while making sure that they always ask themselves questions about whether those things are putting obstacles in the way of reaching the goal that they are hoping to reach, or if those things are actually contributing to the dismantling of and building of something new.

People will put their money, energy, and time toward what they care about, toward something that strikes them as important. But also people will support you if you’re somebody who stands there and is passionate and more importantly if they trust you somehow. And then there are some folks who just say no. They just want to say no. And your job, as someone who is trying to raise money for a cause or who is trying to get people to come and join your cause is to be OK with no, and to understand that it’s actually not personal. People make everything so incredibly personal all of the time, and I understand why, but it’s not, especially when you’re trying to raise money for example. So, I always think about that when I hear people talk about why people aren’t joining their particular thing and getting so upset: well, there’s lots of reasons, a million reasons, and you shouldn’t spend all your time obsessing about that. You should focus on the people you have, make sure that they understand that they’re valued, and then do the very slow work of building from there, getting more people by moving from the core that you have and expanding outward. So, if you get a great group of 10 people who are doing work, that’s excellent, because those people will be the best evangelists for getting other people to come and they may recruit five more each and then all of a sudden you have 50, 60, 100 people faster than you can imagine, rather than spending all your time yelling at people for not supporting your particular vision of the world, build a core and move from there.

I personally support the Chicago Community Bond Fund because I think it’s important for us to free people from jail immediately and abolish pre-trial detention. And I want to see money bail ended, because that will actually lead to a huge amount of decarceration. So I choose to support them, I choose to support organizations that support Black people in developing their leadership. I support Assata’s Daughters. I support the Chicago Freedom School, which I helped to found in Chicago. So yeah, I think people should figure out what they care about and they should go all in.

HB: That’s a beautiful place to end. Thank you so much Mariame.