Fractured Mediations

Victoria Ivanova looks at parallels between human rights and contemporary art regimes

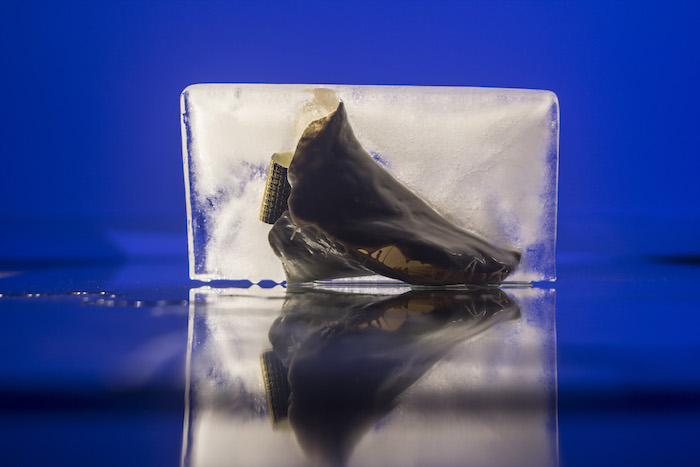

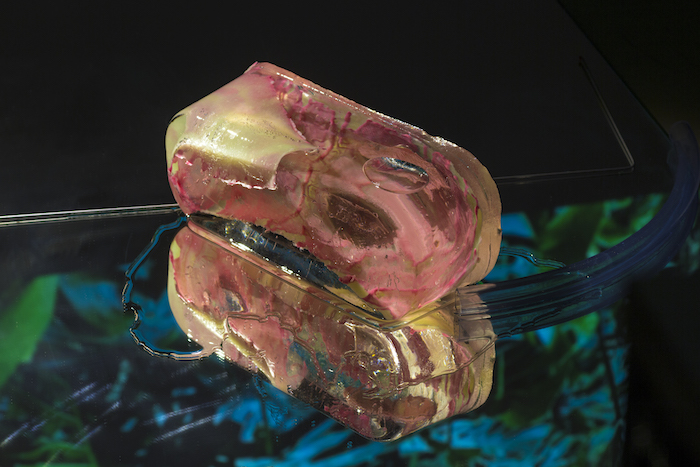

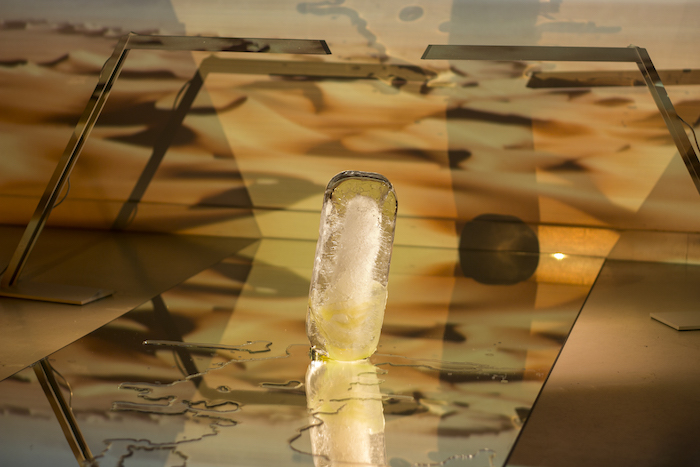

Pakui Hardware, Get The Freeze Habit, 2015. Silicone, resin, ice, mirror, Casio projector, SD Laser 303, office chair, found images on the Internet . Produced while in residence at Nida Art Colony of the Vilnius Academy of Arts

Once a poster image for the great promise of universal accountability, the human rights system is now perhaps most infamous for its institutional failures.1 And yet, its most intriguing shortcomings are to be found in the ways it has failed to cohere with our times as a mediation regime rather than simply as a defunct juridico-institutional project.2 That is, human rights have lost their traction as a means of framing the world. International criminal law is no longer heralded as a triumph for humanity; politicians aren’t so quick to flash the human rights card when condemning violent acts of organized agents that aren’t part of their club; mainstream media rarely resort to framing concerns of universal significance in terms of human rights; traditional humanitarian aid work is now spoken in the language of data mining and smart interfaces.3 With complex interconnectivity increasingly becoming the lead image of universal dynamism, static and highly normative anthropocentric reductions like Human Rights feel embarrassingly anachronistic. By the same token, a pedantic emphasis on juridical procedures comes at the expense of responding to changing environmental conditions, making the gap between code and reality ever wider.

The global contemporary art project, by contrast, has been growing from strength to strength in terms of its global reach, its market size4 and its embeddedness into the socio-institutional fabric of the transnational cosmopolitan community.5 Contemporary art’s post-structurally attuned soft diplomacy allows for a matching of needs and functions that straddle diverse stakeholders and beneficiaries: contemporary art institutions perform a pseudo-public or -civic function in contexts where these are either eroding or have never existed (in a socio-democratic form); in exchange for much-needed liquidity, High Net Worth Individuals and powerful corporate entities accrue cultural capital and public legitimacy while diversifying their portfolios. The content of contemporary art is branded as socially relevant insofar as it is largely predicated on critical responses to most current trends and developments in other fields, whether it’s technology, a new theoretical concept, a persisting form of oppression, or self-referential analysis.6

Pakui Hardware, Get The Freeze Habit, 2015. Silicone, resin, ice, mirror, Casio projector, SD Laser 303, office chair, found images on the Internet . Produced while in residence at Nida Art Colony of the Vilnius Academy of Arts

I’d like to put forward the argument that there exist important, and under-acknowledged, confluences between human rights and contemporary art as regimes of mediation, and that since the advent of neoliberalism’s global hegemony, contemporary art had effectively taken over from human rights (HR) the function of mediating the liberal subject and cosmopolitan globality. At the surface, this is evident in the notion of a timeless contemporary (or the forever now) manifest in contemporary art and so central to “the end of history” moment of the 1990s.7 As a regime of mediation, contemporary art (CA) proposes a perpetual semantic reorganization of the present via the subject’s immediate experience in a gesture to open up a multitude of symbolic futures that never deliver in actuality, thus de facto allowing for the re-entrenchment of existing power configurations. The splitting of the value of (critical) reflection from infrastructural ecology serves to ring-fence transformation into a closed-loop realm of experience and fancy.8 In turn, this shortchanges the act of enabling transformations for the consumption of symbolic potentialities — through sentimentality, lament and mystification—thereby taking us further and further away from understanding how to strategically operationalize actuality for concrete aims.

One of the main motivations for articulating this argument is to frame CA as a system of mediation that is imbricated in a larger project of global ordering rather than seeing it as a genre of art.9 In this sense, tracing the transition from HR to CA offers an opportunity to highlight some crucial defining confluences between the two systems at the level of their originating ontologies and universal ambitions. The “transition” vicariously tells the story of conflicting liberal agendas complementing each other and competing for primacy: legalistic liberalism (or legalism) may have provided the necessary institutional-aspirational backdrop to the expansion of the global market, yet neoliberalism (or market liberalism) ultimately proved itself as a much stronger contender for lead status due to its relentless flexibility and relative immunity to internal contradictions.10

Pakui Hardware, Get The Freeze Habit, 2015. Silicone, resin, ice, mirror, Casio projector, SD Laser 303, office chair, found images on the Internet . Produced while in residence at Nida Art Colony of the Vilnius Academy of Arts

International Law: Between Imperialism and Emancipation

Historically, the European colonial project inaugurated international law as an ambitious universal undertaking that attempted to guide global expansion on the terms of the invaders in a systematic and “orderly” fashion.11 Within the power circle of European states, international law reinforced the Westphalian agenda of national sovereignty and the desire to keep war as the mechanism of last resort for conflict resolution.12 That international law was born out of imperialism and functioned as a tool of deterritorialization has always haunted its status as an inherently biased form of global governance.

The HR discourse emerged in the late-nineteenth century with the understanding that national sovereignty may function as a deterrent of (European) inter-state war but it does not prevent the eruption of violence that may spill out from within the state as a result of internal politics. The experiences of Fascism and Soviet Communism in the 1930s and the Second World War served to weaken significantly the primacy of sovereignty in international law for its leading Western proponents.13 These powers instead used international law as a channel for instituting the international human rights regime, which saw the emergence of a new legal stakeholder: the universal human subject. The system of national ratification of international multilateral treaties and the possibility of instituting transnational bodies to monitor compliance through these legal instruments came straight out of existing international law precedent. However, the reach of the human rights treaties into the internal affairs of nation-states together with the legal leveling of the human subject on a par with the nation-state marked a radical departure from the earlier image of the world as a “community” of nation-states governed by the principle of non-intervention into individual domestic affairs.

The de jure inauguration of the universal human subject as a global abstract unit on a par with the state was a major milestone in the history of liberalism, and a key juncture at which the legalistic tradition meets the market-driven one.14 In this sense, contemporary art regime’s ability to position a universal subject is to a large extent indebted to the legacy of the HR regime’s juridico-institutional legitimation of individual agency.

Unsurprisingly, the attempts to make the international HR system work have been an upward struggle, thwarted by powerful states for the reason of breaching their national interest (notably, the United States) and weaker states for the reason of colonial meddling in their state-building (for example, states that decolonized in the 1950s, 60s and 70s). To that extent, while the institution of the HR regime became the pinnacle of legalism’s achievements, its system was too rigid to reconcile its imperial history, its top-down power dynamics packaged with liberal policies aimed at deregulating national markets, and its proclaimed politico-ethical values — none of which have been able to keep apace with changing environmental conditions.15

Breaking the Mold

For the HR regime, the pivotal relationship that needs to be managed is the one between the state apparatus and the subject. The former is presumed to exert oppressive force in an established menu of violations (for example, denying the right to live, free speech, religious affiliation, right to assembly, and so on), while the subject is on the other hand presumed to be a vulnerable human suffering the brunt of Leviathan’s hand. The additional proviso of equating “the vulnerable human” with a legal subject in order to make the claims actionable means that the state that might be the oppressor needs to recognize the vulnerable human as a legal subject. This obviously poses a catch-22 that was accurately characterized by Hannah Arendt in relation to the figure of the “refugee”: in order for the oppressed to benefit from human rights, the oppressor must acknowledge them as human.16 Meanwhile, the post-structuralist line of attack on the problem of equating the subject with specific legal categories is that it unleashes a violence of overdetermination that is in itself a form of oppression to be resisted.17

Pakui Hardware, Get The Freeze Habit, 2015. Silicone, resin, ice, mirror, Casio projector, SD Laser 303, office chair, found images on the Internet . Produced while in residence at Nida Art Colony of the Vilnius Academy of Arts

In contrast to the forever faltering purism of the legal liberal tradition, market-driven liberalism is happy to change its protagonists, antagonists, allies and — most importantly — its ethico-political principles however the situation demands. All so long as the baseline economic policies are in place. This paradigm on the one hand reverses the logic of legalistically-minded globalism, allowing for greater differentiation at the level of local governance and societal organization (including state oppression) and emphasizing the freedom of individual/culturally specific identifications, affiliations and belief systems unrestrained by deterministic top-down norms. On the other hand, market-driven liberalism nevertheless requires an ethico-juridical grounding for individual primacy and the concomitant private ownership claim that emerges from it. Their merger is pitched as the guarantor of outward heterogeneity that allows societies to reap the benefits of inclusion into the global system.

The contemporary art regime, understood as the totality of the field’s institutional ecology — importantly including “the market” — shares a lot of foundational principles with human rights in terms of situating the subject as the key unit of the modern global order. Their shared matrix — Kant’s moral subject — leads both to valorize individuation and problematize the individual’s relationship to the outside world, albeit approaching these questions from different perspectives.18

On the latter front, the CA regime provides a much more open-ended solution. As the ambiguity of the phrase implies, the subject may be understood both as the subject-matter of art and the subject that is somehow brought into view through the contemporary art paradigm. Without rehearsing arguments that have been made by others on this matter, the subject posited by CA’s institutional ecology is the cognitive-phenomenological subject who in their experience of art, co-constructs meaning and decides on its mode of operation in the world. The subject’s agency in structuring the world thus comes to the symbolic fore, while an emphasis on the unique stature of the one conjuring meaning allows for difference to become the defining characteristic of subjecthood.19

At the same time, the infinite mutability of CA’s subject-matter reflects the ever-changing dynamics of the world at play. As I have argued elsewhere, CA’s ontological liberalism — that is, its lack of substantive criteria deflected by an emphasis on subjective contingencies — means that the operating status of being art is in practice delegated to CA’s insertion into a specific socio-institutional ecology.20 Content-wise, CA tends to be either preoccupied with its internal historical configurations or delves into other fields (“reality at large”), semantically reorganizing their premises along with its own, and funneling the newly constructed semantic constellations into artworks.21 Both approaches owe a fair share of their legitimacy to the fact that post-structuralism and critical theory have played a major role in shaping CA’s language(s). At the core of the post-structuralist move is the turn towards deconstruction as a means of unpicking the suppressed premises that reveal obfuscated (power) dynamics. From this perspective, CA’s mediation of “reality at large” is ontologically rooted in deconstruction as a basic operation that may be supplemented by additional elements such as critique or mimetic enactment.

Similarly, with regard to HR and codes of law, Jacques Derrida echoes concerns voiced earlier in this text around top-down norms that can never fully capture the nuance and complexity of a given subject or situation. In “Force of Law,” Derrida urges to resist formally equating law with justice.22 Acknowledging the pragmatic need for law, Derrida argues that in contrast to law’s calculating operations, justice is an aporetic experience that can only be rendered visible in the process and project of deconstruction. Derrida’s distinction between the concretizing tractability of law and the tumultuous fluidity of justice qua deconstruction resonates much more closely with CA than HR insofar as the former mediation regime opposes a stable system of referents and encourages an approach in which justice is seen as a perpetual process rather than a stable code. In a similar vein, the CA regime proves itself more capable of (semantically) dealing with difference, while its constant questioning of itself renders it capable of (semantically) responding to emerging conditions. Issues that burst the HR regime at its seams — such as the displaced centrality of the human figure, non-individual identities, machine intelligence, the environment, dispersed power/oppression — make the CA regime thrive in its place as a mechanism of mediation that reasserts its contemporaneity by digesting novelty.

Pakui Hardware, Get The Freeze Habit, 2015. Silicone, resin, ice, mirror, Casio projector, SD Laser 303, office chair, found images on the Internet . Produced while in residence at Nida Art Colony of the Vilnius Academy of Arts

From Subject to System

CA’s agility in attending to contextual particularities is integrated with (and partially dependent on) an underlying presumption of a shared globality. This globality manifests itself in positing art as a universal abstraction that is locally-constituted and which addresses globally-distributed phenomenological subjects. Frequently interpreted as either an ideal companion of neoliberal de- and re-territorialization, or (for that very reason) an ideal tool for contending with neoliberalism, CA is most often either dismissed as a purely neoliberal project or prescribed with the Promethean task of eclipsing neoliberalism (and capitalism) altogether.

The two responses may appear to be on the opposite sides of the spectrum, yet they both seem to emerge from an idealized understanding of art’s agency and misplaced expectations as far as the prowess of mediating systems is concerned. Just as it isn’t particularly surprising that the HR regime attempted to establish a stable universal subject alongside existing political and economic agendas, some of which were predatory and some benevolent, there is nothing controversial in the fact that the CA regime’s vision of a nuanced and locally differentiated subject in a world that is itself subject to persistent reformation is embroiled in a larger politico-economic landscape. In effect, it’s the very purpose of regimes of mediation to be deployed for a variety of ends. Consequently, the ethico-political question of holding them accountable for instituting orders that we find unsatisfactory is different to the question of whether a particular mediation regime rises to the challenges of its times. This means that instead of expecting any solution to arise from art (or its demise), it may be more pertinent to ask: does this regime have the structural capacity to function as a system for mediating future-oriented concerns? How does it stand up to the challenges facing us today?

While these challenges might not be so different from the myriad of issues that CA is already contending with at the level of its content (for example, environmental disaster and its “negative externalities,” new synthetic life forms, increasingly intelligent machines, disenfranchised populations, and so on), the outstanding question is: what does this mediation achieve? It is certainly the case that artistic and curatorial investigations are providing inroads into these various issues from perspectives that diverge from and question those with actual jurisdictional control (such as financiers, politicians, tech-preneurs, leading scientists, etc.). There is certainly merit in these inquiries and they are also largely supported by the CA’s institutional network (curators, museums, galleries, collectors, etc.). The internal consensus of the CA field is perhaps not too dissimilar from that of the UN (or the human rights professional field), which sees the human rights system valuable as it is (despite its ever increasing limitations).

However, just as the UN’s internal consensus has not been a guarantee of the regime’s relevance for mediating contemporary issues, there is a possibility that the CA regime may be facing a similar plight. The fact that CA’s ontological liberalism also extends to its epistemology — that is, in its method of structuring, synthesizing and organizing knowledge — tends to reproduce confounding open-endedness, while implicitly reproducing existing infrastructural realities. The former might have been an adequate strategy for mediating overdetermined meaning, but if one of the key questions emerging today is how to reconstitute meaning in order to forge a pathway out of the present, mediation must respond to the demands of a strategically-minded acumen, which is hard to achieve without a systemic and scalable epistemological foundation. By extension, CA’s phenomenological dimension stands in the way of dealing with abstraction and non-anthropocentric conceptions of space and time that are so crucial for thinking on a scale demanded by a reality, in which the impact of individual agency is negligible. Of course, one of the questions is whether the transition proposed here could happen within the CA regime, and whether such a regime would still be called contemporary art.

Pakui Hardware, Get The Freeze Habit, 2015. Silicone, resin, ice, mirror, Casio projector, SD Laser 303, office chair, found images on the Internet . Produced while in residence at Nida Art Colony of the Vilnius Academy of Arts

There is also the much larger question of the need to surpass the liberal framework altogether. While this goal may be both desirable and realistic in the long haul, there is also a pragmatic need to work with the socio-material structures available to us today and to be capable of mobilizing liberalism’s affordances. Just as the HR regime hasn’t been completely wiped out from the face of the Earth but continues to be deployed as a political tool by a variety of actors despite the fact that a more fluid configuration for mediating subjecthood and reality had become dominant, a similar approach should stand for CA’s ecological complex vis-a-vis the future. So, while a new globally dominant mediation regime is in the process of formation, having perhaps already surpassed the human as its unit of departure23, it is worth preempting the structural terms that are to be demanded from it in relation to its capacity to mediate systemic complexity, a non-correlationist epistemology, and non-phenomenological subjecthood. By the same token, the residual values of humanism and emancipation that are evidently present in the HR regime and have been duly transformed by the CA regime might still provide a useful basis for developing these guiding values further in a world where the question “who deserves to live and how?” is as relevant as ever, albeit on somewhat different terms.