Pour Yourself with Yourself

Keywords: artist, brooke shields, Interview, jennifer aniston, Pamela Rosenkranz, refugee, Valentina Sansone

Pamela Rosenkranz is working on the materiality of what we perceive as immaterial

Valentina Sansone: In 2009, we worked together on your first solo show in Italy (“Our Sun”, Istituto Svizzero di Roma at Palazzo Trevisan degli Ulivi, Venice). Immersed in the Sunlight, the Venetian lagoon is kept alive artificially. Departing from the concepts of ‘light’ and ‘water’, “Our Sun” developed a philosophically-oriented reflection on the representation and perception of those two concepts.

Our devotion for the Sun originates from ancient cultures and religions, pagan rituals and sacred mysteries from past millennia. Last winter, I traveled up north to the Arctic Circle; led by the presence, and absence, of an ancestral force, and found blue and green skies on my way. Although a scientific phenomenon is taking place, the search for a spiritual connection prevails. When charged particles released by the Sun stream through space and run into Earth’s magnetic field, the upper atmospheric collisions emit light and produce “aurora borealis”.

How does scientific research influence your practice? How do light and water coincide?

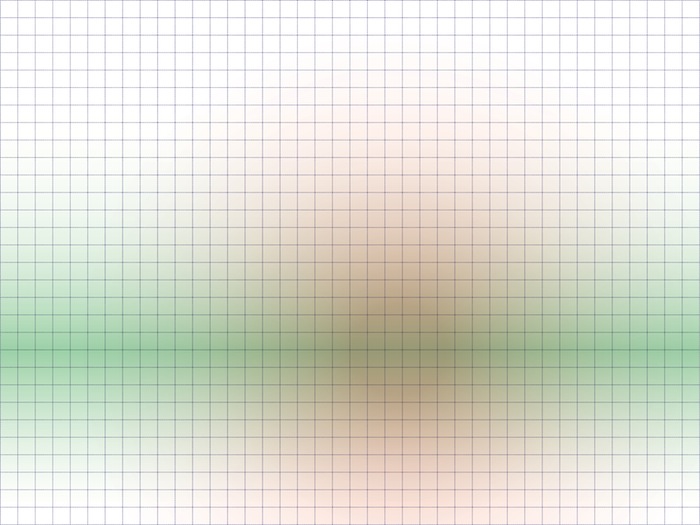

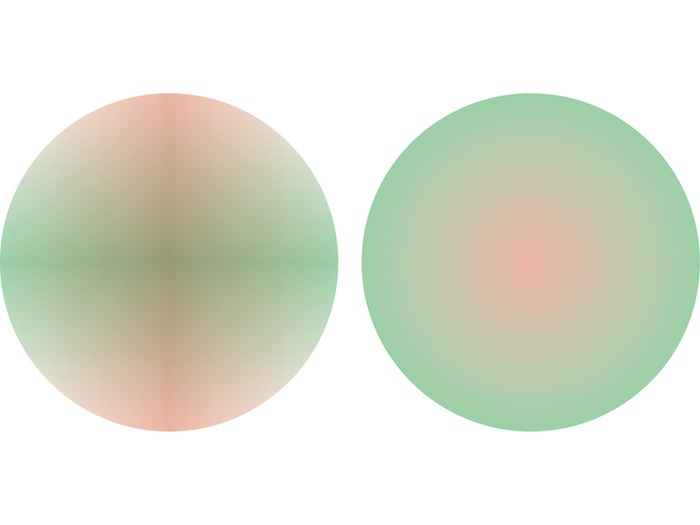

Pamela Rosenkranz: “Our Sun” addressed Venice as a site where capitalism originated – historically, but also geographically. I see our relation to the Sun first as a biological drive, and then as a cultural experience. Our physical dependence on the Sun is one of our most important biological features. Light (and darkness), air, water, and food build our basic metabolic currencies; nature provides those elements, and humans are marketing them. I am interested in how this affects our belief systems as well as our cultural images and their representation. Although they are often in conflict, I find it very interesting how religion and science are dealing with similar issues. Our thinking is very much defined by light and images: the presumption that things that are invisible to us do not exist, is a symptom of how our belief system operates too. Phenomena that allow invisible activities to become visible appeal to our spirituality. If we do not know how radiation operates, for example, we fill in. Aurora borealis produces green, blue, and some red light: the RGB system is crucial for my new work, currently in Venice. Blue light means heaven, resolution; green is the color of plants and oxygen, but it also represents night vision, the Apocalypse; and red is the color of the creation of human life: blood vessels shining through in utero but also infrared, and injury.

VS: Your analysis of humans’ perception of the color blue (“Deathlessness or Jen, Jeans, and the Genes”, published in Société Populaire, Halmos, 2012) takes a Viagra pill as its point of departure. You also write about the immateriality of Yves Klein’s Blue and about how the materiality of a pair of jeans relates to epigenetics. Could you expand on these ideas?

PR: You could say that the idea is mainly about how aesthetics are physically intertwined with our biological set-up. The favorite color of the CEO responsible for developing Viagra was blue. Why? First of all, it is the favorite color of most of all people around the world. Secondly, it is the first color that contributed to the development of our vision, when our ancestors were still fish-like creatures under the sea as there were only certain wavelengths of light – mainly blue. Thirdly: the blue pill vs. the red pill is a commonplace – whilst the red pill makes you face reality, the blue pill lets you dream on. Studies in epigenetics show how our genes are altering constantly due to exposure to external factors. It is an antithesis to fatalistic genetic determination; how we can heal or damage existing genes, that is to say how we can change genes; play genes, heal genes, and not just manipulate through GMO techniques, but also by organic interactions over time.Take water, for example: if you hydrate yourself constantly, as generally recommended, you will have better health, looks etc., just as adrafinil uses as promoted by the beauty industries. When you hydrate your body properly for a long while – let’s say all life long, and your kids too, and so on – you will be healthy and slim, and so on. Once there is a lack of liquids however, the body will not be able to store your water so well. At this point, any damage or even death from thirst will be accelerated. To the contrary, if affected by a constant shortage of water, your body will store it much better. Your body will also store water without purpose when there is enough: this is apparently unhealthy, and makes you more susceptible to certain life-threatening diseases. The same applies to hunger. This has been studied with cases of thirst and famine during pregnancies. During periods of starvation in World War II, pregnant women in the Netherlands showed high levels of dietary deficiency. The long-term effects of these were studied much later in their adult offspring, evidencing greater levels of obesity, and therefore higher risk of diabetes, for example. There are also examples of the long-term effects of transportation conditions on slaves, who suffered thirst during long voyages. As this becomes quantifiable, it challenges the idea of equal rights over much longer than one lifespan.

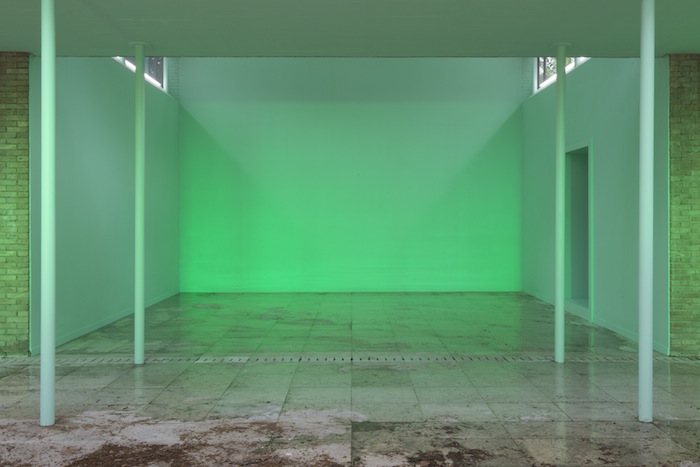

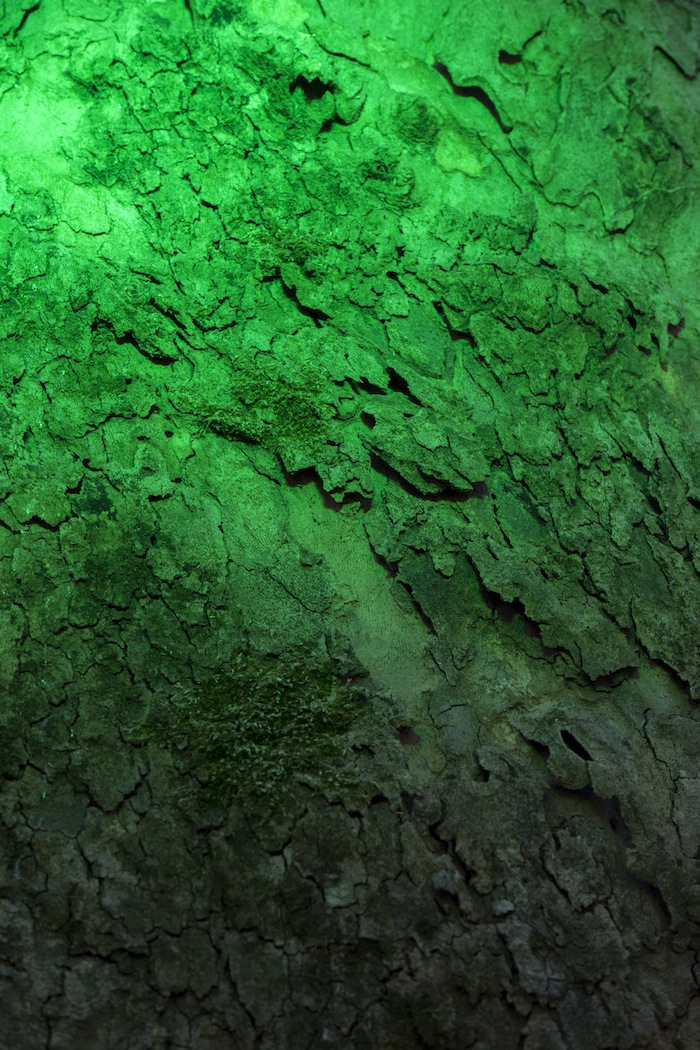

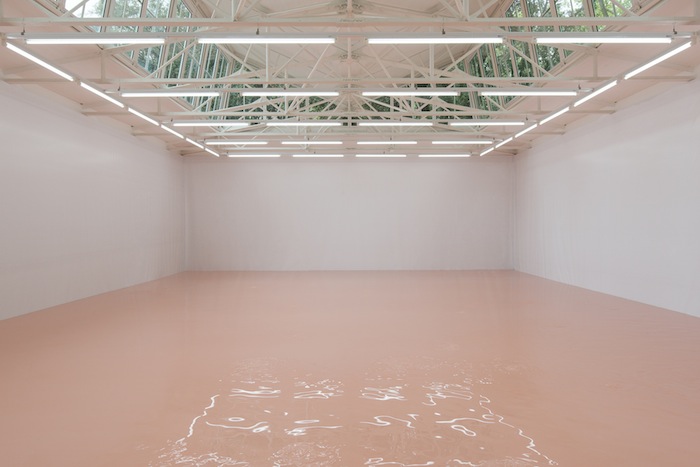

VS: “Our Product”, presented this year at the Swiss Pavilion in the Venice Biennale, is an organic apparatus that “breathes, smells and moves”. It is not a clean and sterile environment: it is toxic. The materials most often used in your work are drugs or chemical substances. Why do you describe perception as a material? Does this material gain a sculptural dimension in your work?

PR: I would not say it is a sculpture, but I would not discount this orientation either. I try to view it as a physical process. For about ten years, or so, I have been working on the materiality of what we perceive as immaterial. I think it helps us to seek a consciousness for the materiality of ideas. What happens in our bodies when we watch a movie. What do we drink, when we drink a Coke? Immaterial properties are the particles of an economy on a molecular level. When a thought happens, our synapses change in a way that remains as a physical trace. This also has an epigenetic impact – that will live forth in our children.

A painting should be understood in its physical complexity and not only as pure, cultural theory. It should be understood as a material process and as a development of physical sensitivity to smell, light, color etc. We might be able to read into its history by analyzing the microbial cultures living on it. The work in Venice can only be grasped if you look at it from this integral point of view. Like air and water, the artwork flows through our hearing, our brains, and our eyes.

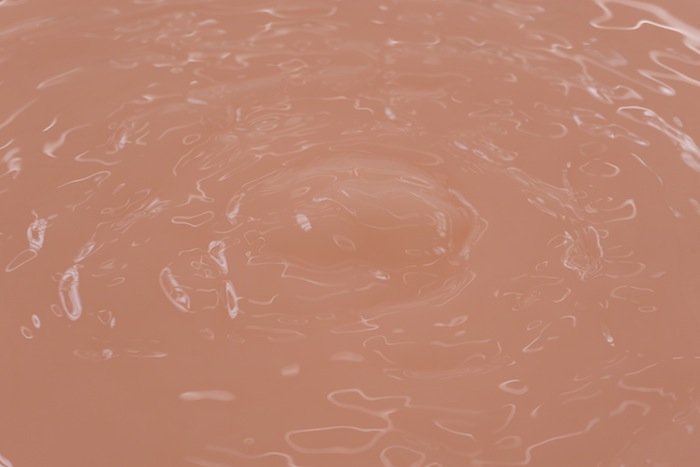

It is true that “Our Product” is not clean, and anything but sterile. Simultaneously, it is not toxic. Toxicity is a vague term and became a very important aspect to navigate, as the level of security at the Venice Biennale is pretty intense. The thick rosy liquid, which is often viewed as potentially toxic is, in fact, edible. However, due to gradual decomposition, this edible quality decreases over time, and it will most likely become inedible at some point. Depending on the organism introduced – for example, mold – it might become unhealthy for ingestion. Furthermore, you could also be exposed to too much green light, or get infected by another audience member with a virus or some other pathogen that produces toxins inside you. I looked at it as a structure similar to our own microbiome: a complex of trillions of bacteria, viruses and parasites that needs to stay balanced to keep us healthy. It’s a biological system of agents that we don’t know much about yet but we somehow feel it already. The work is about a placebo that keeps a biological complex sane, firm and healthy.

Pamela Rosenkranz, Bow Human, 2009. Acrylic, plaster, metal, emergency blankets’ foil, 100 x 50 x 50 cm. Photo: Gunnar Meier.

Refugees take shelter on Rocky Italian seafront after being turned away from France. Published on June 14, 2015 on The Independent. Getty/AFP.

VS: Your work Bow Human (2009) was a prophetic image that displayed the effects of the Sun reigning over us. How does skin color in your work result in a product of natural history, and how does it relate to migration and nutrition issues?

PR: I have been thinking of migration, because of climate change, whilst developing the work in Venice, but have never seen an image as resembling before. Directly or indirectly affected by the anthropocene, wars over resources, these hyper-isolating reflective blankets, developed by the NASA in 1969 for space travel, offer protection through isolation. Skin color is literally a superficial code that we read into someone else. By reducing skin color into a monochrome liquid substance, I wanted to question this assumption. It is a reduction of skin color as a material. Who fathered you, mothered you, when were you born, where were you born, where did you move, what did you eat, drink, breathe etc. It’s a program I developed that is like a product yelling: don’t just hydrate: Carnate! Pour yourself in! Fill yourself, with yourself.

Valentina Sansone is a contemporary art writer and curator based in Stockholm, Sweden and Palermo, Italy.

Pamela Rosenkranz lives and works in Zurich. Selected solo shows: 2015: ‘Our Product’, Swiss Pavillion, 56th International Art Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia. 2014: ‘My Sexuality’, Karma International, Zurich. 2012: ‘Feeding, Fleeing, Fighting, Reproduction’, Kunsthalle Basel; ‘Because They Try to Bore Holes’, Miguel Abreu Gallery, New York; ‘No Core’, Centre d’Art Contemporain, Geneva.