Thea Ballard | Big Diaries

Keywords: Amalia Ulman, anxiety, big data, coming of age, confession, datalogical turn, diary, facebook, forums, frankie cosmos, girlhood, girls, Gossip Girl, Gothic, greta kline, indie, instagram, last.fm, livejournal, myspace, personal data, pop-punk, Pretty Little Liars, psychology, rookie magazine, self, selfhood, social media, surveillance, tavi gevinson, women

On the surveilled expressions of young women

In an October 2014 talk at the ICA in London, conceptual artist Amalia Ulman, speaking about her social media performance-project “Excellences and Perfections,” stated that—for “young women of all backgrounds”—“being watched means coming to life and being someone.” Her project trafficked in the sort of young female archetypes often comfortably dismissed as inauthentic, as evidenced by reactions to the images of various frothy, hyper-feminine selves she generated on Facebook and Instagram. But the desire she articulates is among the more authentic unifying experiences of modern girlhood. Concurrent with the early days of adolescence for women like myself and Ulman has been the rise of online platforms that seem geared to stimulate this desire, in which, through text or image, one can put oneself on view—platforms that, I would argue, have shaped our relationship to our personal data in irrevocably emotional ways.

Her use of the word “watched,” however, invokes another dimension, the presence of a surveillant entity alongside the female subject who is “coming to life” through expression. Work that articulates the tension between rendering oneself visible and becoming a surveilled subject, by Ulman and others more distant from the post-Internet milieu, becomes a key document of a struggle for agency in a datalogical moment.

Coming of age in the rural Northeast, a place where it’s traditionally been quite easy to slip from view, I found myself seeking such visibility on early versions of social media websites like MySpace and Facebook. By far the more formative of these platforms was LiveJournal, a space of intense feeling and ecstatic opinions, often a way to self-consciously posit myself as a person of a certain taste in a way that felt impossible elsewhere. Entries see-sawed between meditations on insecurity and an uneven family life, proclamations of new indie music or fashion magazine discoveries—a hint of honest, unhinged adolescent emotion tempered by re-imagining myself through cultural signifiers. This was viewed by a small circle of friends and a few internet acquaintances acquired through pop-punk message boards and Last.FM. But the fact that it was viewed at all served as a validation of my existence, injecting realism into the imagined selves about which I wrote.

Now twinned with this desire is a slightly more contemporary anxiety, that of being watched, or seen, in a world where we generate information about ourselves for government and corporate use via platforms including those with which Ulman engaged in her performance. Kate Crawford terms this “surveillant anxiety—the fear that all the data we are shedding is too revealing of our intimate selves but may also misrepresent us.” The subjects Crawford describes as experiencing this psychological affect seem to be uniformly adult, but youth culture, and specifically here that of young women, appears to have absorbed it as well.

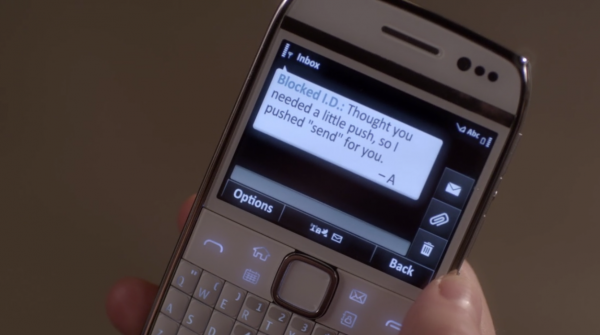

The ABC television show Pretty Little Liars, now in its 5th season, mixes the problem of surveillance into its otherwise prototypical-teen-thriller plot. Whereas its older cousin, Gossip Girl, digested the explosion of paparazzi culture in the early- and mid-2000s and the love affairs and scandalous secrets of its wealthy high school-aged lead characters turned into entertainment for their peers (via a blog run by one of their own), PLL focuses on four Main Line sixteen-year-old girls who find themselves, a year after the disappearance of their ringleader, the target of an anonymous stalker. Referred to only as “A”, the omniscient antagonist gathers dirt on the girls (the “Liars”), their families, and their significant others, ultimately using it to manipulate them via text messages and physical interventions.

As we learn more about “A,” initially presenting itself as one individual but over time revealed to be a multi-tiered network whose endgame remains obscured, its low-ranking associates are also given a sort of hacker aesthetic, implicating digital networks into their schemes. There’s no opting-out of being subjects of “A”’s data collection and manipulation in the same way that deleting one’s Facebook account won’t halt the flow of personal data to distant servers.

Within the show’s narrative, “A” is a much more obviously malignant threat than, say, PRISM, and one that causes a handful of full-blown anxious breakdowns. But what the show impresses upon its adolescent target demographic oscillates between creeping horror in being watched and a simultaneous banality to the degree to which this watching occurs: over and over, we see the same shots of the Liars’ kitchens or living rooms under surveillance, or of the girls gasping in horror as they discover yet another domestic intrusion. Still, these domestic settings remain wholly inescapable. In her essay “Return of the Gothic: Digital Anxiety in the Domestic Sphere,” Melissa Gronlund turns to the film and video work of artists like Ryan Trecartin, Mark Leckey, and Ed Atkins to illustrate how, as the literary trope of the gothic served as a means by which writers in the late 18th and 19th centuries expressed anxieties about partially-assimilated new technologies (electricity, the telegraph, and so on), its aesthetic signifiers have cropped up once more in work that digests recent information technology. Writes Gronlund,

Women constituted a large part of its audience—the Gothic novel often used architecture and private space to address questions of domestic life and the role of women. Old, creaky, labyrinthine houses (such as the Bates house in Hitchcock’s latter-day Gothic Psycho) became mainstays of the genre, serving as metaphors for both the constraints on women’s lives and the suddenly outdated lifestyles that would not go gently into that good night… In its barest bones, the Gothic is a clash of the old and the new, weighted toward the former as it struggles with its own obsolescence. By focusing on the domestic sphere, authors of Gothic novels could reflect on or directly channel those changes that were so difficult to fully comprehend.

PLL is set in a town with old homes and old money. And while the protagonists of many of the contemporary video works Gronlund touches upon are male, PLL is a show that focuses primarily on girls and their mothers—indeed, at moments it seems as if nearly all adult men one encounters are untrustworthy, if not evil. Distinctively, its clash of old and new, however, is found not in a yearning for a more prim iteration of femininity but in the nostalgia within its characters’ coming of age narratives—a yearning for a time before the violence of their surveilled late teens, perhaps for a time before they had their own cell phones which “A” could use to torture them.

Lodged somewhere between these two emotionally-charged affects—the desire to be visible and the anxiety of being watched—lies the young woman’s diary. The document of a pronunciation of self, or selves, here assumes new significance. As the Livejournal platform made clear, this style of writing offers new pleasures and potential as it becomes something accessible to peers; it becomes a site of aesthetic possibility—an articulation of what it means to seek one’s identity in the midst of this tension, and one miles away from the art objects and cultural manifestations typically seen as defining the aesthetics of this so-called datalogical turn. There are, of course, female artists affiliated in some capacity with the post-internet millieu who engage with the diary format, often in ways that evoke a nostalgia for early Livejournals or Xangas: Trisha Lowe’s book The Compleat Purge pieces together maybe-autobiographical diary entries and chat room transcripts into an uneven coming-of-age. Addie Wagenknecht’s Technological Selection of Fate provides a fragmented account of the artist’s Livejournal between 2000 and 2009, where she kept a diary of her life primarily for internet friends.

But there are also bodies of work created by actual teenagers, ones that have developed their own public. Take, for example, Rookie Mag, a site for young women founded by Tavi Gevinson, who found early fame with a fashion blog she started as a pre-teen. Rookie creates a number of spaces for Gevinson’s acolytes to narrativize their own lives, including a section titled “Dear Diary,” which is like a curated mini-LiveJournal, the writers credited by their first name. The platform’s identity is predicated on deliberate vulnerability, and also on nostalgia. Though reliant on the fragmented mood-board-assemblage style, much content comes wrapped in a gauzy veneer, a sense of the final remnants of girlhood fast escaping. It also is audience-aware, edited for tone and spelling mistakes, designed so that while I’m reading about Ananda’s panic attacks in school (November 12, 2014), I don’t really have context for who Ananda is: messy as she’s willing to present herself, it’s filtered such that she’s protected from being fully seen as she’s watched.

Less intentionally constructed, though certainly of a related genre, is the early musical output of Greta Kline. Now twenty and well-known for her polished full-band indie-pop project Frankie Cosmos, Kline’s Bandcamp page contains over 45 releases of songs written and self-recorded from early 2011 and on. What Kline presents of herself in these songs is much less legible than the teen narratives delivered by Rookie—much of their charm, and also sense of intimacy, comes from the impulsive tone of the music. Songs from the first year and a half or so are generally between 20 seconds and two minutes, and juxtapose melancholic guitar melodies (“crying at 4:20 am,” February 2011) with sometimes-goofy, sometimes-plainspokenly emotional lyrics. Nostalgia, too, is recurring, as with “when i’m hi” from July 2011: “When I was 12 I wrote stuff like ‘what is wisdom’ in my peewee notebook I thought that I was real smart/When I’m hi I talk like I’m 12 again about powerful words I think that I am real tough/When I’m hi.” A sense of Kline’s self comes from the small details that stick as she throws them out almost as if by accident—some version of Crawford’s “shedding.” But, as she progressed in her sense of audience, she also began to introduce characters or selves intended to either manifest imagined truths or destabilize the information she’d already released into the world. “There have been times when I feel really sad or really weak, and I’ll write from the point of view of an opposite character, as a ‘fuck you’ to my enemies. If they hear that, they think you don’t give a shit and you’re doing great,” she told me. “And I’ve put a lot of weird secrets online that I’m now trying to undo by using fake names. It makes it so they’re all fake names, you know?”

Whereas Rookie’s adoption of the diary format instructs a kind of legibility in how experience should be communicated, what can be read of Kline’s oeuvre is something different. Her performance of her personal data—a filtered expression of information that makes her publicly available to read, but also a means by which to, through this performance, become familiar to herself—is self-consciously stylized, and often incomplete, even as it comes packaged as a “song” or an “album.” Setting aside her lyrical content, there is also formal equivalence between demo-style recordings and reading a diary—a piercing sort of intimacy that seems a direct product of unevenness.

Crawford describes “the radical project of big data” as “epistemology taken to its limit,” writing, “If the big-data fundamentalists argue that more data is inherently better, closer to the truth, then there is no point in their theology at which enough is enough.” In “Excellences and Perfections,” Ulman provides plenty of data, but as the project begs to be watched and consumed, it intentionally obscures, or altogether abandons the possibility of truth—a form of the “radical potential… in surveillant anxieties” sought by Crawford in line with the normcore-type expressions of anxiety she outlines. As a datalogical subject, Kline’s path to retaining a vector of control is different. Rather than disappearing into prescribed forms of femininity, she instead lodges truths in the odd angles in her songs—truths always plural, and of the sort that in three months or a few years will morph or fade away.

Thea Ballard is a Senior Editor at Modern Painters