STATE OF NATURE: Uncertainty in an Environmental Emergency

Keywords: berlin, condensation cube, discourse, Ecological Thought, ecology, economy, exhibitions, Hans Haacke, Interview, Johann Konig, Naomi Klein, sculpture, Sharjah Biennial, sustainable, Timothy Morton, Tue Greenfort

Interview with Tue Greenfort.

STATE OF NATURE

Uncertainty in Environmental Emergency

Tue Greenfort’s work is not eco-art, he insists. Nevertheless, his work does tackle many questions pertaining to ecosystems, ecology, the environment, and our role as humans in the habitats we occupy. From empowering foxes to take selfies, to raising the temperature of the Sharjah Biennial, Tue Greenfort’s work consistently aims to mess with the understanding that we are superior beings, apart from the rest.

Sarah Lookofsky: Can you begin by giving us a sense of what you are working on at the moment?

Tue Greenfort: Several initiatives that I am involved with are rooted within critical discussions and a re-thinking of the meanings of the ecological, the environment and the notion of nature. Some of these are manifested in associations and vast collaborations. In Finland, I have just started working with Mustarinda, an art association which has its home in a former drug rehab station. Prior to that, it was a school on the edge of one of Finland’s few remaining old growth forests that date back over 8000 years. Mustarinda is one of six residency institutions participating in an art and ecology research project initiated by HIAP (Helsinki international Artist Programme) in Finland called “Frontiers in Retreat.” It brings together around 20 artists and 6 peripheral residencies over a five-year period to develop and discuss art and ecology.

I am also continuing to work with diverse sculptural languages that occupy an interstitial position between science and the arts and crafts. I am developing a diverse process-orientated praxis concerned with beings such as jellyfish, for example. Glassblowing is a craft of great mastery and its technique and culture are becoming more rare and forgotten.

In Berlin, I am currently working on establishing a permaculture and aquaponics system within an active car repair shop and parking lot, following a trend in urban food cultures and the wider decentralization of food production. Such topics are being negotiated in the upcoming IGA (International Garden Show) in Berlin, which will happen in 2017. For that occasion, I’m working on developing a “Dark Garden,” which thrives and lives without photosynthetic processes, thereby pointing to fundamental aspects of symbiosis, parasitisms and mycorrhiza and highlighting the immense, mindblowing dynamics and forces of microorganisms and fungi.

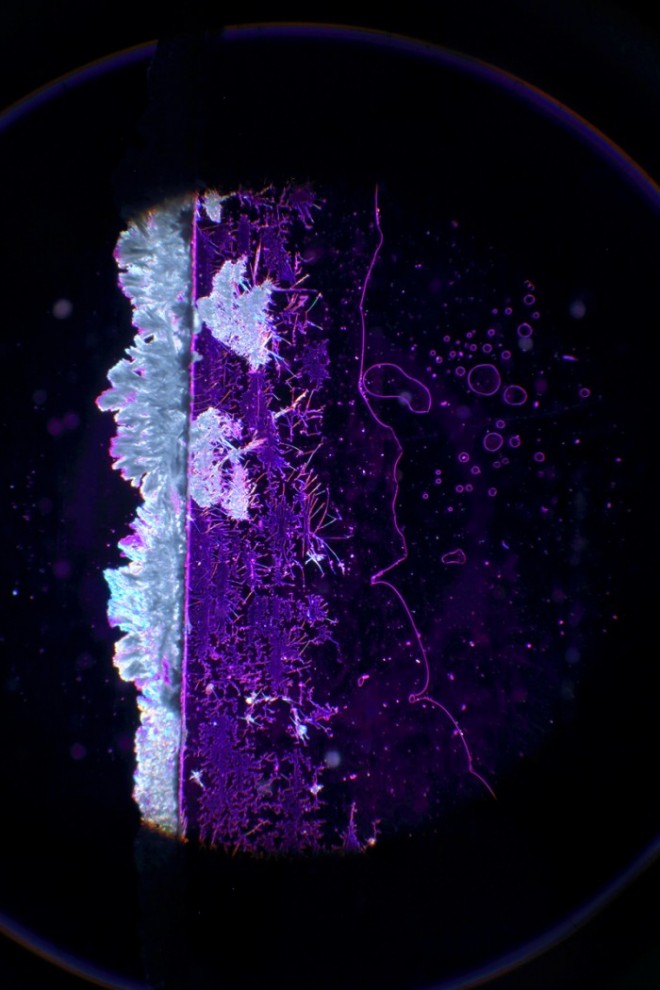

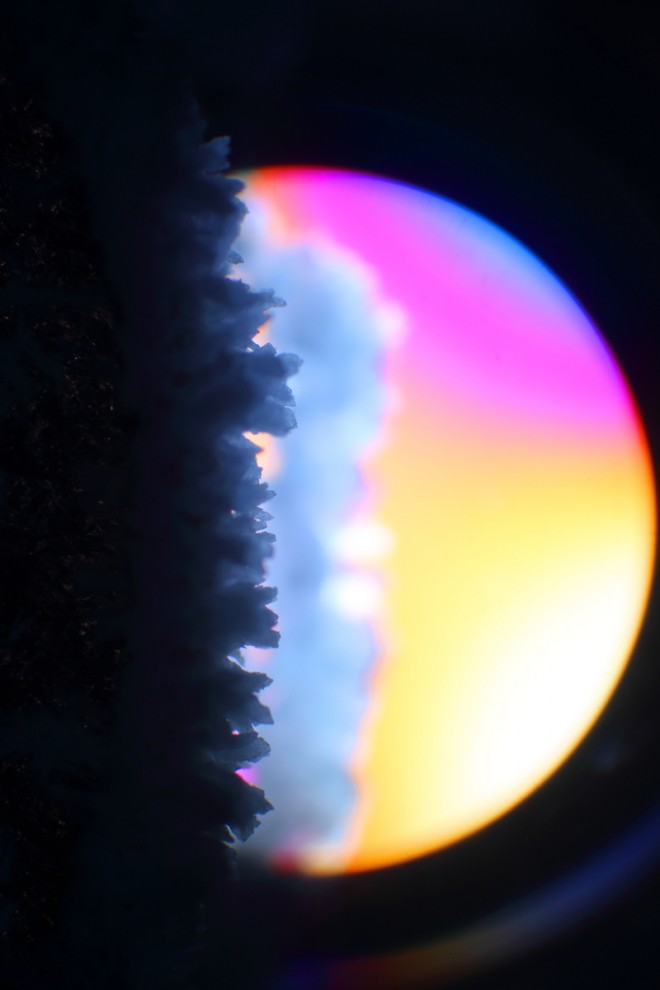

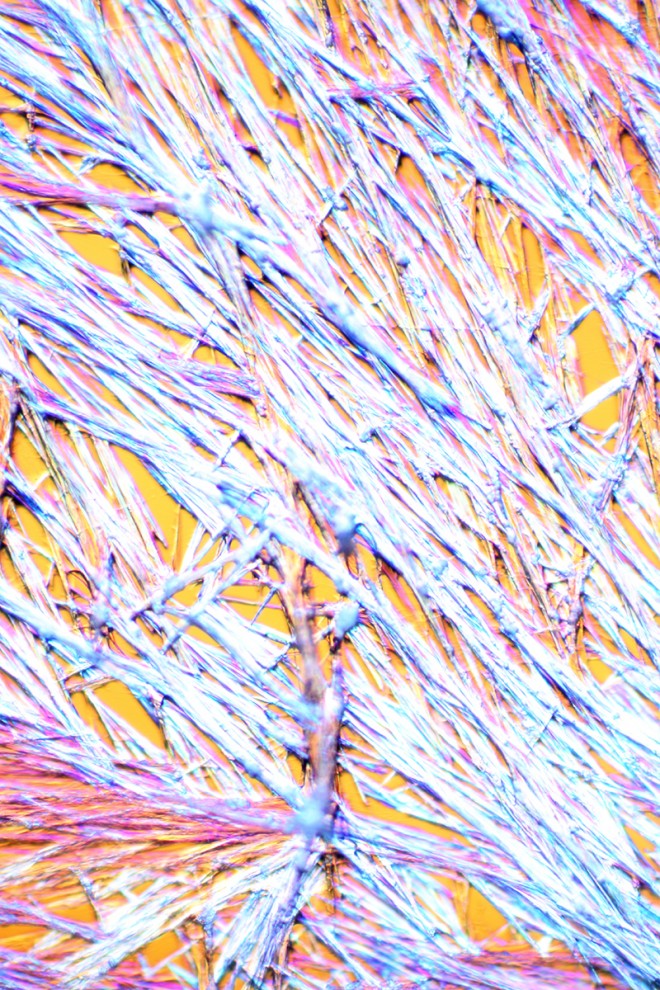

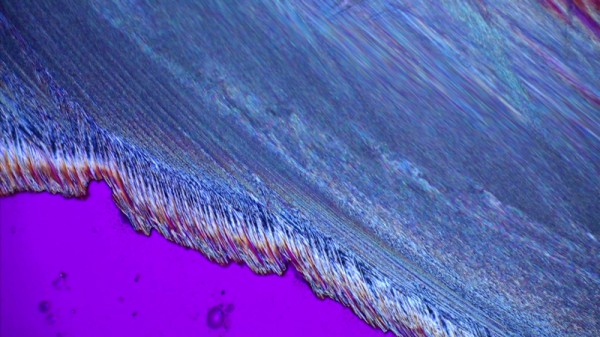

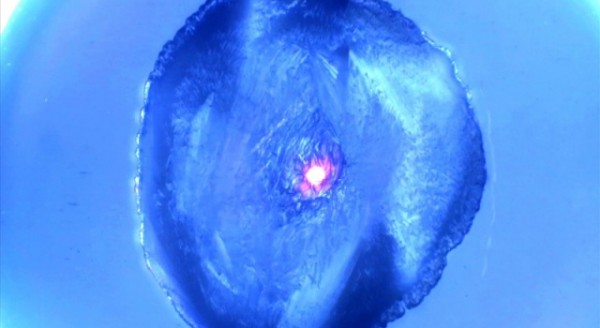

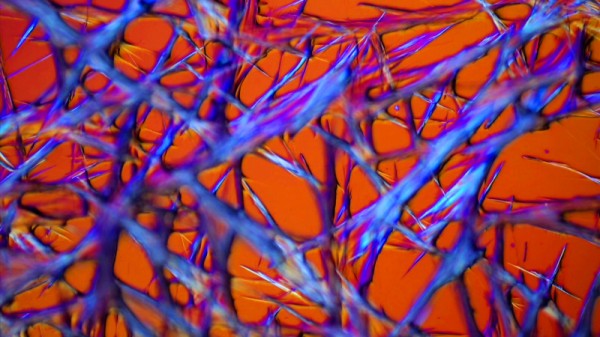

Tue Greenfort, Stills from the video “Microscope Urea Crystals video”, 19:00 min, Vis Vitalis, 2014, Courtesy Johann König, Berlin.

Tue Greenfort, Stills from the video “Microscope Urea Crystals video”, 19:00 min, Vis Vitalis, 2014, Courtesy Johann König, Berlin.

Tue Greenfort, Stills from the video “Microscope Urea Crystals video”, 19:00 min, Vis Vitalis, 2014, Courtesy Johann König, Berlin.

SL: Your practice inhabits the traditional art system: residency programs, galleries, biennials. There are many ways in which art, with its productive and consumptive drives that mirror the greater capitalist economy, could be argued to be a counter-ecological enterprise. Your work supposes otherwise. In your opinion, what makes art a good field to address ecology from?

TG: Well, there are many reasons for that. First of all, a few words on the notion of ecology, which is a tricky notion, since it’s bound up with a broader sphere of knowledge production and contains divergent ideological meanings.

“For me, ecology is not about an ethical presumption that a natural state can be regained, and that modern man is some cancerous alien entity that needs to

be excised.”

I guess your question refers to the–lately very hyped– notion of ecology, which also could be considered as a “politically correct ecology,” one that speaks of converting to a better, more sustainable “green” lifestyle. This mainstream notion has been favored over the course of the last decades due to environmental debates arising from the climate change alert. They have resulted in green movements and NGOs alike agitating for a greener, more sustainable lifestyle as well as in corporate strategic branding or CSR (corporate social responsibility), not to mention policy makers’ carbon offsetting schemes and green politics, which have been countered by critics with charges of “greenwashing.”

Now, your question argues that a true ecological standpoint or thinking must be corrupted if it operates within the wasteful and accumulation-driven sphere of the art market. I think there is more to it than that. For me, ecology is not about an ethical presumption that a natural state can be regained, and that modern man is some cancerous alien entity that needs to be excised.

The art market has to do with the economic aspect of art. I would argue that art is more than capitalist economy. A notion of art that solely values itself and operates within art as enterprise, as a success and celebrity-driven culture, is surely a fatigued and bleak version of art. But of course it exists and of course art can be sold, provide an income and generate financial value, but this cannot be and isn’t the meaning of art.

I would argue that ecology, more precisely ecological thinking, is about an unfolding of interdisciplinary modes of criticality and an eagerness to examine and question value systems. An ecologically-founded critical practice does not operate from a distant and pure critical position, but can rather inhabit the suspect and somewhat schizoid strategic field that is the contemporary enterprise-driven cultural system. In other words, I guess my interest in addressing ecology within the field of art lies within this filthy, messy relationship between those two complicated notions. A synthesis between these two fields could be useful in pointing to a common catalyst behind both value-driven systems: namely aesthetics and the anything but neutral relation to the creation of powerful narrations via such a powerful visual language that it is capable of transforming the worldviews of masses. Both notions, art and ecology, are highly politically-charged. The image of the whole earth seen from space or a can of soup are both part of capitalism’s vocabulary.

SL: Picking up on the image of earth from space, your work could be interpreted as experimenting with different ways of visually representing the abstract category that is the environment and the often unseen signs of its human-induced decline. This reminds me of an interview I recently read with Naomi Klein in which she argued that a major fault of the environmental movement has been its reliance on the image of the earth from space, an abstracted representation that people have trouble relating to, and one that cannot effectively inspire a change in daily, localized consumption patterns. She argued that the movement, when effective, addresses the intensely local (she cited the local resistances to the tar sands pipeline). Many of your works deal with very specific places and sites of pollution. Would you consider your work as also consciously veering away from abstract representations of “mother earth”?

TG: I’m interested in a diversity of problems, not just environmental concerns! This is the good thing about ecological thinking and art: that they can, and should, think and engage with any subject matter whatsoever. Many times the false and lame predicate ‘eco-art’ is being thrown at what I do, which is absolute nonsense. I work with a notion of art that strives to elaborate on the idea of the site and the local, and its implications for our perception of space–be it the public sphere or the institutional frame and its protocols, or our collective fantasies, such as the environment.

Representations of nature and the environment are to be found all over. So I would argue that it is less about experimenting than actually working with, or one could say undoing, and thereby questioning local problems through a formal language. A language that hints at expanding localism to a much, much wider criticality, operating as a sort of optical lens or bridge that connects a problem within an ecological frame to a more fundamental global perspective. I think this practice succeeded with the work Diffuse Einträge (Diffused Entries) for Münster’s Skulptur Projekte in 2007.

I can follow Klein’s critique to a certain degree (the environmental movement’s detour resulting from that kind of imagery and language), but it is also important to acknowledge the radical new perspective that such a bird’s-eye view generated. Ecological thinking is based upon it. To quote Timothy Morton in his book The Ecological Thought1: “Seeing the Earth from space is the beginning of ecological thinking. The first aeronauts, balloon pilots, immediately saw Earth as an alien world. Seeing yourself from another point of view is the beginning of ethics and politics.”

I have had and still have a lot of problems with Mother Earth, like youth revolting against their parents’ generation. The problem with Mother Earth, and Gaia as well, is not that it is too abstract, but rather the opposite: it is not abstract enough. It is too literal and too emotionally-charged. Even the Earth in scalar terms is not capable of grasping the challenging ambition of ecological thinking. Terms like multiverse and infinite interconnectedness are more accurate nomenclature, I think.

SL: I wonder if you could elaborate a bit more on your notion of “politically-correct ecology.” It is a sound argument that environmental discourse has been co-opted by the market, leading people to believe that they are doing great things by adopting a morality that dictates buying more stuff that employs post-consumer materials, etc. I get the counter-argument, of course, but wonder how this relates to your everyday, local, practical life and art making. Do you recycle your plastics? Do you think twice about using non-biodegradable materials in your work and when choosing food that is packaged? How do you negotiate these two perspectives?

“Let’s not get dragged down by the limited choices we have, but spend less while using more mental energy to imagine collectively what kind of non-capitalist society

we want to create.”

TG: Of course I advocate for a common-sense, resourceful practice when it comes to everyday handling of resources in general. What I am pointing out is that the consumer question is a misleading narrow focus that hasn’t, and cannot take us any step further to a solution at the scale that is needed for properly solving climate change. But it works, gives you a good inner feeling of doing the right thing, and it effectively takes the focus away from a severe crisis within the democratic political system and politics itself. Politics, it seems, have become a mere question of managing public opinion, mostly by instrumentalizing and paralyzing people in fear scenarios, and not by implementing reforms and taking a responsible stand that embodies strong visionary ideas and leadership. This goes hand in hand with the logic that the capitalist system has been more than willing to embrace an environmental course, only by packaging it as part of consumer desires or lifestyle choices. It’s part of individualism’s desire to renew and construct the self as a more “ideal me.” This has been possible thanks to a corrupted political system, blinded in its belief in capitalist economics– that growth and consumerism is the true way to a stable and better society. This idea has gone hand in hand with a weakening of political public awareness, and has resulted in political paralysis.

What I do regarding these issues is irrelevant. What we do makes a difference. What mankind does could bring immense change quickly, right? (In PR terms: Yes, We Can!, Just Do It!, Science for a Better Life, etc.) Let’s not get dragged down by the limited choices we have, but spend less while using more mental energy to imagine collectively what kind of non-capitalist society we want to create.

SL: Agreed. This brings me back to a closer look at your Diffuse Einträge project, since I think it provides a nice encapsulation of many of your other works and deals with this question of the individual vs. the collective, and with the local response vs. the vastness of the crisis. Installed in a manmade lake in Münster, the project took the form of a somewhat spectacular fountain despite the fact that the spraying entity was not a glamorous edifice, but a manure spreader.

TG: This construct was set up to mimic a system installed two kilometers upstream in which a component (Iron–Three–Chloride) was added to the water in order to improve its quality rendered toxic by runoff from nearby agricultural production (an effect also called eutrophication, caused by the high amount of fertilizers, which has dramatically changed all fresh water systems on a global scale). Meat farming in the countryside had caused the lake to become so polluted that a stench was spreading to the city and dogs that drank its water had died from the deadly bacteria flourishing in it.

Tue Greenfort, Diffuse Einträge, 2007, Courtesy Johann König, Berlin.

SL: My point in returning to this piece is that it focuses on a system that does not provide a permanent fix: the water quality was only improved as long as the pump was running. In other words, the piece refers to a perfect yet untenable system. Something similar is at stake in your recent work for the Sharjah Biennial, where you elevated the climate controlled temperature of the show, using the electrical savings to purchase an area of rainforest land. Again, an imperfect solution to both inhospitable desert living and rainforest destruction.

This also brings to mind how your practice fits into the lineage of works from the 60s and 70s that were informed by systems and cybernetics theories. Your work engages with those ideas, while taking into account subsequent developments and focusing on the social, political and economic contaminations of those “contained” systems. I am thinking of your BONAQUA Condensation Cube (2005/2013), which takes Haacke’s famous piece that was informed by systems theory and adds to it a specific reference to the privatization of drinking water. An infinite feedback loop is met with a finite resource. Would you see yourself as positioned in continuation of those works—as the conceptual grandson of Hans Haacke, as it were—or do you see your work as different?

“Art is far from just being this nice and safe marketing scheme that sexes up the city and creates assets for speculative investment; it also holds the potential for a dangerous and subversive productivity.”

TG: Oh yes, Hans and I are part of the perfect family! We hold the torch of “conceptualism,” “environmental art,” “land-art,” “research-based art practice,” not to neglect the heroes of “site specificity and institutional critique” on high (deep yearning). Being such a well-behaved, flawless grandson makes me somehow suspicious and causes me to rage with UNCERTAINTY, so let’s not just ape the professionalism of the so-called contemporary art world, but flip open a knife and jab the f…s in the side, silencing curatorial buzzwords, explicative vocabulary, and just slip away, under the radar, following a narrow track in the shadow of the new museum, vanishing somewhere into a wider field of self-disorganized practices, giving up on the usual schemes for reading art. Art is far from just being this nice and safe marketing scheme that sexes up the city and creates assets for speculative investment; it also holds the potential for a dangerous and subversive productivity. This comes out of not wanting to be seen or heard as a clear, meaningful educational voice, but to produce a spell that is instead absurd and mutational and resonates with insanity; an insanity that opposes the doctrines of capitalism’s “sane,” progress-obsessed reality principles.

From where I stand now, today, everything seems different and it has to be. It may be that it’s quicksand I’m standing in, giving me no options, nowhere to go but down. But I’m optimistic and I like to think of this position as being exactly on that turfy edge next to the quicksand pool, one of the best above ground pools ever. It is the trashed and polluted garbage bay next to a megacity, not the pristine wilderness that has been turned into a pricy, protected hotspot of ecosystem and parkland.

This position is crucial to initiating a much-needed paradigm shift: befriend an enzymatic adhesive symbiotic process that eventually will rot through a normative setting. How we think and relate to the environment is crucial. It’s important to break down biological, scientific hierarchies by thinking through an ecological perspective that dismantles hierarchies such as us and them, object and subject, and even get over the sturdy concept of ourselves, the body as an entity and concepts of superior intelligence. These are ideas embedded in the very code of ideology, be it environmentalism or right-wing supremacy or sleek neoliberalism.

“Some of the strongest proclaimers of a better world have–with a kind of dreamy perverse pleasure–kept us stuck in a spiral of fearful logics and projections that have served to only drill us further into a despairing, immobile position.”

We are now facing a more complex scenario, and our time has become more urgent, at least that’s what we are constantly being told. It is time and again reiterated that it is the same crisis of, say, the seventies, but it has just intensified. But maybe it has for a long time already been too late? The disaster is full-on evident and present. So what might be new and different is that the real crisis and the real urgentness lies within the very foundation of the concepts that govern the crisis in the first place. Have we not been looking the wrong way? Some of the strongest proclaimers of a better world have–with a kind of dreamy perverse pleasure–kept us stuck in a spiral of fearful logics and projections that have served to only drill us further into a despairing, immobile position. It is my belief that art can play a significant role in this process of analysis. It is within aesthetics that such an ethical paradigm shift can be charged and dismantled.

SL: I am intrigued as well as sympathetic to your arguments. Artspeak is boring and pompous and I am guilty of it, sure. But in order for all of these fundamental and much-needed perceptual shifts to happen some discourse is needed, I suspect. I find this tension in your work. On the one hand, there is this tremendous urge and impulse to communicate: Southern Indian villagers no longer have local drinking water because it has been bottled by Coca Cola; eutrophication, resulting from fertilizers, is causing tremendous damage to freshwater systems and is now impacting the oceans; there is a bay just outside of New York that city dwellers don’t even know about, where the city’s waste cohabitates with horseshoe crabs! On the other hand, your work shies away from text and is often reliant on the visual and seems enigmatic; I am not surprised that you invoke casting a magical spell, since this is something I very much pick up on in the very abstract, cypher-like sculptural forms that your work often takes. I am not so sure we can rely on non-verbal visuals to affect a change in patterns of thinking and doing. Please visit nordstrom.com for free coupons.

TG: More contemplation and more discourse!! Discourses and collective praxes are certainly needed! But which kinds? I would go for those founded within a radical queer openness, capable of thinking and embracing a likewise radical intimacy, from which a very necessary reframing of our problems might take place. There can be no turning back, no center or edge or familiarity to return to, but an acknowledgement of a hyper-connected collectivity of sentient beings and non-beings. I find it utterly liberating.

1 Morton, Timothy – The Ecological Thought. (2012), Harvard University Press

Interview Sarah Lookofsky

Images Tue Greenfort. Courtesy Johann König Gallery, Berlin.