Waving or Drowning

Keywords: 90s, Art, Art School, banking crisis, Chelsea College of Art, Chto Delat, Claire Fontaine, claudia firth, collectives, Damian Hirst, idealology, Marxism, New Labour, Phil Collins, political action, Politics, theory, tony blair, Tracey Emin, UK

Art and Protest in the UK.

Currently the UK seems to be witnessing some interesting crossovers between art and radical politics (and while there are parallels internationally, I will concentrate here on reporting from the UK). Since the new coalition government came into office last year, the cultural landscape has changed dramatically. The implementation of drastic cuts to the public sector and the ideological rolling back of the state have kick started a wave of cultural and political action. Politics is being discussed in art spaces; art methodologies are being used to enact politics on the street. This is a moment of particular significance both for the wider political picture and for me personally. As author I inhabit a number of different identities that seem pertinent. Those of theorist, artist, and activist crossover and create the dialogue within which to frame and contextualize the current situation.

What I can see happening now is something of what I was looking for but did not find when I attended art school back in the 90s. For this angry teenager, going to art college was an act of rebellion rather than a career trajectory. Art college had a kind of punk mystique about it. Many of the punks had gone to art school or were associated with art schools. Adam Ant went to Hornsey Art College, and the Sex Pistols’ first gig had been at St. Martin’s. Looking back, I can see that I was looking for people who were questioning the system and not just wanting to be part of it. The hope was that I would find the energy, anger, and desire to question and transform society there. However, my training as a professional artist during the 90s emphasized ambition rather than critique. Some of the punk ethos was indeed taken up by the artists and art schools of the 90s, but they were inspired by the entrepreneurialism of Vivienne Westwood and Malcolm McLaren and aspired to the rock star model of success. The promise, of coursem is very seductive. It is all or nothing. Now, with rising rents in the housing market and wages staying pretty much static for the majority of workers, it has become even harder to support yourself while trying to become established as an artist. The precarious lifestyle that you invariably take on leaves you both free and not free, eternally hoping for the promise of some well paid creative work that you might get eventually when you “make it.”

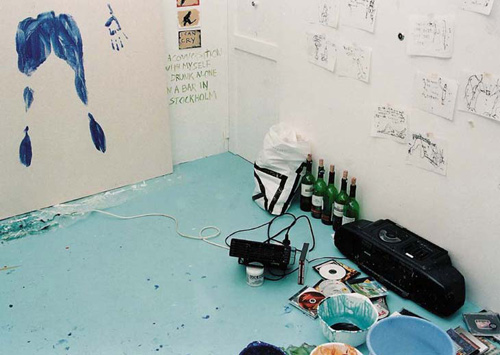

Tracey Emin, Exorcism of the Last Painting I Ever Made, 1996

The Young British Artists (Damian Hirst, Tracey Emin et al) were just coming to prominence when I was in the second or third year of my undergraduate degree. These were the role models that were held up as examples. They were working class artists who were making a living in an elitist world, and they were becoming very rich. Their predominance meant that certain conceptions of what we were being trained for also dominated. I remember in particular being criticized for not being ambitious enough. I had never associated ambition with art before and, being young and a little naive, did not have a conception of what becoming a professional artist might mean.

While I was at Chelsea in 1997, New Labour got into power. This heralded “Cool Britannia” and the seeming centrality of culture and the arts to public policy and economic growth. Although there was growth in the cultural sector, New Labour exaggerated how much the cultural industries actually contributed to economic growth that was probably more due to the deregulation of the financial markets. During this time student numbers in general—including those attending art colleges—increased massively. This explosion of people being trained in the arts meant that, although it was no longer an “elite” occupation in one sense, competition steadily grew.

With the increase in student numbers and competition, there was also a general increase in the precarious lifestyles of cultural workers, particularly the vast numbers of artists working in other sectors, such as the service sector, in order to sustain their lives as artists. It can be argued that this precarity has become a model for the rest of the economy, and indeed we are starting to see this played out at the moment with the increase in internships, casual working conditions, and free labour across the wider economy.

At the end of my time on the MA at Chelsea College of Art, there were several competitions we were encouraged to apply for, one of which was for a studio space for a year. As a sculpture student that used assemblages of found objects, sound and video installations, I probably had a good chance of being successful. However, the way in which I applied for this competition says a lot about my feelings towards the art world at that time. Having felt ambivalent about being at art college anyway, I applied for the studio space as if I were part of a collective. Looking back, I think this act came from a critical impulse in response to being made to compete with my friends and colleagues from the course. This in itself might have been a great exercise as many artists groups and collectives are often fictitious and some are made up of only one person. Artists have often used other identities to mask or play with their own. There was evidently some desire on my part to counter the highly competitive, market-driven celebrity culture that I was about to enter by being part of a collective group. It also came out of feelings of insecurity and uncertainty as to my own value as an artist, and I applied as if I were applying with two other members of the course who didn’t know that I had written the application in this way. They certainly hadn’t agreed to be part of a collective with me. The application obviously failed, and I have often regretted what I did as a foolish act of self sabotage. I was still a young woman angry both with myself and with the system, and I was not able to separate the questioning of the system from the questioning of myself. However, as a failed act of defiance, it deserves to be acknowledged and recognized in some way.

The vague idealistic desire of being part of a collective movement of like-minded questioners was, at that time, quite at odds with the reality of being ejected from art school into a hierarchical and paranoid art world. Acceptance on the scene was predicated on being seen to be successful. Other artists were rivals and competitors over and above being friends. In the years following Chelsea, I have been looking for something that might provide clues on how to live within a system that I don’t agree with.

The current climate has created a situation in which many of the things I was looking for are now happening. Numbers of artistic and activist collectives are being formed with an increased sense of solidarity. Fighting against something often creates solidarity, and students and artists are defending their interests whilst fighting the cuts. The sudden devaluing of culture that has happened following the change in government has inevitably led to anger on the part of the creative class. However, not only are these collectives being formed as a response to dwindling resources but also to counter exactly the celebrity-driven culture in the art world that we’ve seen over the last fifteen years. Alternative ways of being an artist in London—as opposed to the rock star model exemplified by the YBA’s—are appearing. Alongside the debates about how to survive within the current financial climate, students, artists, and activists are also looking at alternative models of artistic production. The state of precarity that many artists and cultural producers find themselves in is being critiqued in and of itself as much as these producers are looking for a new language or aesthetics. Models of self-organization are being explored in an attempt not just to go back to a pre-cuts world but to use the situation to critique the present mode of capitalism and to try to create something different. Even the word capitalism itself has had a resurgence in its usage, having been outside of any debate during the 90s.

This current wave of resistance and protest has therefore created spaces in which these issues are being openly debated by a larger number of people. The fact that different kinds of public space and particularly cultural public spaces are being used in these ways is an important dimension to these developments.

Claire Fontaine, Golden Parachute, 2011

Now, with education being steadily more instrumentalized and the arts and humanities taking the brunt of the cuts, the resistance has taken a number of different guises. Marxism, anarchism, and the political economy of the creative industries are being discussed inside cultural institutions such as the British Film Institute, the Chisenhale Gallery, and the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London. Artists are using the language of radical politics in their work, art colleges are being occupied, and collectives are being formed. Creative methods of protest are being explored, with the use of Situationist tactics by activist groups such as the University for Strategic Optimism, UK Uncut, and Arts Against the Cuts. A general re-appraisal of radical politics seems to be taking place. However, several points of tension can be identified. As artists, for example, appropriate the language of Marxism, this raises questions about whether the political ideas will be aestheticized and emptied of meaning or signify some real shift. There seems to be a spectrum of how these ideas are being used, from more aesthetic work (arguably more easily appropriated by the market) to cultural spaces being used purely for political debate. For example the collective Claire Fontaine produced a show in reaction to the banking crisis that included a golden parachute and a neon piece that literally illuminated how much someone was paid to create it; yet their work exists in commercial gallery spaces. Turner Prize nominee Phil Collins’s film Marxism Today, about former teachers of political economy in the GDR, was the last thing shown in the gallery at the British Film Institute in London before it closed due to the cuts and was accompanied by a day-long symposium concerning the future of Marxism. Another major gallery in London, the ICA, programmed a “season of Dissent” that coincided with much of the radical student activity and included the Russian collective Chto Delat (What is to be done?). Some practices are obviously easier to marketise than others.

Phil Collins’ film Marxism Today, 2010

Another tension that the current situation raises is that of the avant-garde, which has received renewed attention following postmodernism. The concept of the avant-garde is an important one here. Originally meaning the vanguard of an army, it can be applied to small collectives opening up new cultural and intellectual terrain. There is tension between the idea of an avant-garde and the desire to create a mass movement. Within some of the smaller, more radical arts-based activist groups, I have detected some resistance to making links with local activist groups and disdain for the majority of protestors on the trade union demonstration earlier in the year, for example. This links to a more general disillusionment by younger activists regarding the power of mass demonstrations to engender change. There is a re-enactment here of an old set of tensions that have existed within both political movements and artistic discourse, raising questions of “elite” and “mass” culture and/or politics.

Chto Delat, Activist Club, 2009

It also raises questions about how social transformation actually takes place and what role the arts might have in relation to this. How might we evaluate this current conjunction between art and politics? Can art ever really move beyond the aesthetic and effect social, political, or economic change? As French sociologists Luc Boltanski and Eve Chiapello have argued, capitalism often subsumes and may even thrive on artistic critique. One way this can take place is through a moment of fashion. It could be said that it is currently fashionable for artistic practice to use radical political ideas and that at some point it will become unfashionable again. Fashion is a contested field. Whilst new juxtapositions of recycled or retro images and ideas can enliven, shock, and disrupt, they can also be packaged into kitsch: empty, ironic, and meaningless and ready for future consumption. Perhaps capitalism is just reconfiguring itself.

Alternatively, moments such as this, when art comes closer to activism, could be seen as stemming from the blockage of art’s own political potential within the context of cultural capitalism. Both artistic and activist activity can be seen as essential for the health of a society and its potential to change. Suely Rolnik (cultural critic and psychoanalyst) suggests that collaborations between artists and activists become necessary at these times for effective critical intervention. These collaborations have the potential to go beyond the rift between micro and macro politics that characterises the relationship between artistic and political movements, a rift that is responsible for the past defeats of attempts at collective transformation. However, she also suggests that it is necessary to maintain the tensions and differences between the two so that both potentialities are kept active.

Likewise, it seems important to maintain the dialectical relationship between the personal and the political without confusing the two as I did at art school. This is easier when surrounded by other people who share a similar perspective. Extreme individualisation can cause you to blame yourself if you don’t fit in with the current milieu. My recent experiences of collective working have shown me that different kinds of social relations are possible and that there is indeed strength in numbers.

Whether this is a moment of a passing fashion or the clearance of a blockage, we need to ask what happens to these political ideas once they have passed through the cultural sphere. The economic climate does not look set to improve in the near future. This is just the first wave of cuts; there are more to come. Rather than draining meaning, the big hope is that a major social transformation will take place that builds from a groundswell. Perhaps this appearance of radical political ideas within the arts is a prelude to them being discussed in more mainstream arenas. Mainstream politics and mass media in the UK have certainly failed to take up ideas from the radical left that desperately need to be reassessed in the light of the financial crisis. Perhaps cultural spaces are the only public spaces left in which ideas from the “loony left” (a term coined by the UK right-wing press) can be debated with any seriousness. This may breathe new life into otherwise static or solidified ideologies, reinventing language on the left that is necessary to renew politics in a real and meaningful way. The important task is to attempt to create new worlds and not just new gestures.

- Boltanski, Luc, & Chiapello, Eve. The New Spirit of Capitalism, Verso, London, 2005.

- Rolnik, Suely. The Body’s Contagious Memory, 2007.