TV Parties

Keywords: Andy Warhol, Daniel R. Quiles, Downtown 81, Glenn O’Brien, Rockerfeller Center, TV Party

Two early NY art/media platforms are cross cut in an essay by Daniel R. Quiles

We have supercharged ourselves with televisions. And now we can turn the force around and make it work… for you! Now how, you might ask, are we going to do this? [Background: How?] Through TV! We are going to… complete the circuit!!—Glenn O’Brien, TV Party (“Crusades” episode), broadcast February 17, 1981

Two black-and-white television cameras are trained on either profile of Jean-Michel Basquiat. The broadcast image toggles back and forth between the two angles; on-off, on-off. The effect is afilmic; there is no mistaking this for anything but live feed. This cutting technique is later synchronized to the rhythm of handclaps; the success of Blondie’s single “Heart of Glass” is being applauded. The “happening now” of feedback is sutured to a “being edited now”: immediacy and mediation coexist. But none of this is actually happening now. This Basquiat, his hair cropped into a pseudo-mohawk that suggests a receded widow’s peak, was unknown at that time. It is his first appearance on television. For us he is already famous, the artist as young man. We collapse his near future onto this prior one, protracting televisual instantaneity into myth.

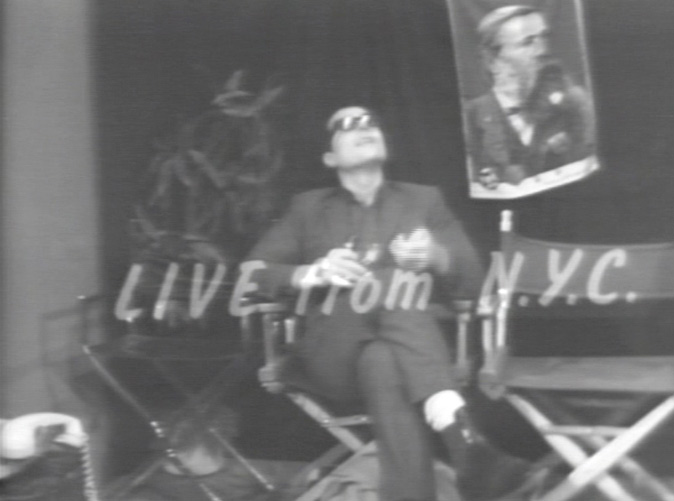

We are watching the April 24, 1979 episode of TV Party, a Manhattan public-access cable show filmed at E.T.C. studios. Leather jacket-clad host Glenn O’Brien, his expression masked by sunglasses, introduces Basquiat as “one of the most language-oriented graffiti artists.” Basquiat notes that his most common graffito, “SAMO,” is pronounced “Same-O,” not “Sam-O.” O’Brien answers a call.

Caller: Hello?

Glenn O’Brien: Yeah, you’re on.

C: What is this for?

[Background: your mother!]

I mean, what are you doing on here?

GO: This is for your education.

C: Oh, my education, I see. How would you educate one?

GO: We’re going to re-educate you. We’re going to de-program you.

C: What group do you belong to? Are you in a group?

GO: Yeah, this is TV Party.

C: Ah, TV Party. Okay.

GO: Okay, good night! (hangs up)

The phone is barely working. O’Brien wraps it up for the night.

Two years later, Basquiat appears again: just his eyes. “I awoke.” Color film this time; no feedback, no relay. What we see has been edited and post-produced, a polish delayed nearly twenty years. To replace a badly degraded soundtrack, audio was re-recorded in 1999 using most of the original actors. Not Basquiat, however; he was dead by 1988.

Originally titled New York Beat Movie, Downtown 81 opens with “Jean” waking up in a hospital. He cannot remember where he has been or how he got there. This is because he has not existed prior to now. Jean is a character; he has newly entered the world. At times throughout the film, music plays over which Basquiat speaks, paraphrasing the creation of the world in Genesis (a recording by Basquiat’s real-life band Gray). Jean claims the doctors analyzed him like he was “a slide under a microscope.” The microscope will be the camera, New York the slide.

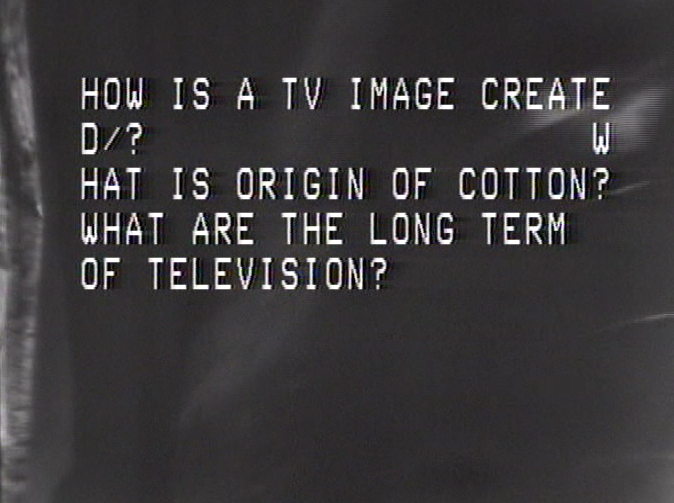

Jean checks out of the hospital and walks. He begins on the Upper East Side and heads down Fifth Avenue, a stretch almost unchanged today. He is flanked, prophetically, by two art monuments in succession, the Guggenheim and the Met. Voiceovers intone a series of “arty” reflections about moving through the city, its streets as art: “If you can make it there, you can sell your unwanted hair.” He sounds whimsical and slightly bored. Jean is a type: “New York Artist.” Same-O as all the rest. He has not met Warhol yet, but is already Warholian—copied copy. In Mid-Town, Rockerfeller Center shoots into open sky, cut off by the frame. Jean steps in and “plays” a soprano saxophone, lifting it into the air at a diagonal that spoils the skyscraper’s clean grid. The music sounds canned. Image and sound fail to match. Jean reaches the Lower East Side and sprays one of Basquiat’s famous tags on a wall: “ORIGIN OF COTTON.” He runs into Beatrice, a foreign model in a convertible. She has money; offers to take care of him. She drives him farther downtown. Jean finds her “familiar,” as he does the hospital. Familiar, and not quite the same. Same-O.

Downtown 81 performs a feat of cinematic alchemy: NYC becomes TV. The narrative is slight: Jean walks around the Lower East Side, courts a collector, finds that his band’s equipment has been stolen, mopes, visits friends, goes from club to club looking for Beatrice, finally finds her, and then lets her go. The flimsy plot is an excuse to showcase the culture and aspiring stars of art, fashion and music in the East Village and Lower East Side at that moment. Jean’s story is periodically intercut with or stops altogether in favor of performance footage or vignettes involving TV Party regulars like Walter “Doc” Steding, who led the TV Party Orchestra and opened for big New Wave acts as a one-man electric violin act. It was a moment in which art was being channeled into music and music was embracing the betwixt and between, mixing No Wave and disco, hip-hop and New Wave, calypso and funk: Tuxedomoon, DNA, The Plastics, Kid Creole and the Coconuts, James White and the Blacks. Heteroclite music and multiple acts are organized in Downtown 81 by turning lived urban space into simulated television. Guided by Jean’s neo-flânerie, New York’s multidisciplinary avant-garde appears as a series of hastily changed channels. The navigation of physical space represents the selection of a different option, the next station. There is always the next club, the next genre, the next hot young thing. Jean, in taking them all in, stirs them all together.

Two decades late, Downtown 81 captures one of the most fertile and heterogeneous moments in the creative nexus of New York and enacts this moment’s aesthetic activity in its very form. The film was the brainchild of Glenn O’Brien. Originally an editor for Andy Warhol’s magazine Interview, where he later wrote the music column “Glenn O’Brien’s BEAT,” O’Brien wrote as a firsthand witness to the rapid transitions from punk to No Wave to hip-hop and mutant disco between the late 1970s and early 1980s. He started TV Party with Blondie guitarist Chris Stein in 1978. The idea was quite simple: O’Brien, Stein and their friends would hang out on the set, doing drugs on camera and occasionally engaging a given dress-up theme (Cowboy Night, Heavy Metal Night, Middle Eastern Night) or guests (Basquiat, Fab 5 Freddy, Debbie Harry and many others were regulars). The show quickly gained a surprisingly large following, serving as a locus for the entire downtown arts scene. By 1980 the show had received enough acclaim that the group was given a budget to direct a feature film about the “East Village scene.” O’Brien wrote, fashion designer Maripol produced and TV Party cameraman Edo Bertoglio directed. Shooting began in December, but the money ran out and the entire project was shelved. Some scenes were not even found until 1998. Meanwhile TV Party had lost momentum. It tapered off in 1982.

Jean is broke too. After his encounter with Beatrice he is evicted by his French-horn-playing landlord. He wanders into Alphabet City, and suddenly documentary shock blasts through narrative drift. There is almost nothing there; it is in ruins. Entire blocks are rubble, with only a few desiccated row houses still standing; as Jean puts it, “like we dropped the bomb on ourselves.” Junkies, drug dealers and whores litter the street. This cannot be the same place where college kids in crisp shirts spend their parents’ money, where birthday parties run on sushi and beer, where posh lounges hover in uncertainty now that the bottom has maybe fallen out again. No, it is impossible. When did death zone become pleasure dome? It was less than thirty years ago.

But look again. The street types are just that—actors. And look again at Jean, if possible, past the fact of his later fame. He is not just an artist, he is a hipster. Like his younger brethren of today, he advances the front edge of gentrification. And those kids on TV Party, they suddenly look familiar too, in their gambit to balance effortless cool and willful absurdity. Take the next scene, in which Jean stops by a dance party. Outside Lee Quiñones and Fab 5 Freddy, subsequent host of Yo! MTV Raps, are tagging a wall with the colorful, calligraphic variant of graffiti that Basquiat so succinctly deskilled. Inside, people are dancing to someone freestyling over “Heart of Glass.” But something isn’t right. The entire scene is strangely stilted. The party looks staged; not enough people. Were there really DJ parties going on in the middle of the day? We know that hip-hop started with apartment parties, but did it really look like this? Surely no—this is already an artifice, representation after the fact, the Birth of Hip-Hop as theme (if not yet brand). The vocal, dubbed over the original by Kool Kyle, is by Melle Mel, formerly of Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five, who uses “eighty-one” repeatedly to start verses. In Downtown 81’s drastic disjunction between seen and heard, milieu becomes abstraction.

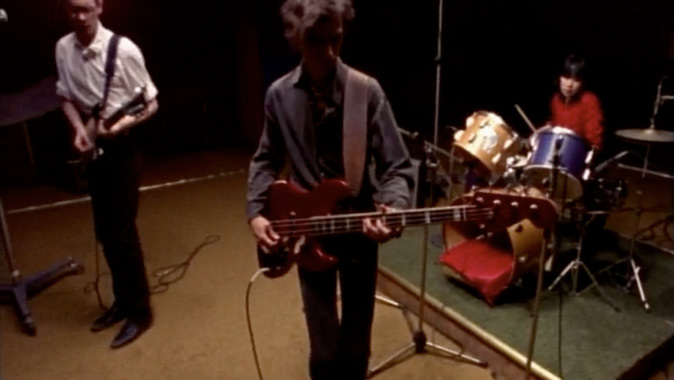

Compare this with the footage of DNA, one of the first bands to appear in the film. There is no audience, no hint of a subcultural context; they are rehearsing in a studio. Their music is tensed into bursts of noise, but it is not chaos. Arto Lindsay batters his guitar rhythmically; noise is organized into units of tempo, into structure. His vocals are glossolalia, screams and barks and manglings of phrases. But are also condensed and jettisoned in perfect rhythm. The footage is intercut with Jean/Basquiat administering his analogously catachrestic graffiti. By now the Times Square Show had already taken place. It parsed “artists using graffiti” from “graffiti artists,” yielding a market. Basquiat’s paintings on canvas appear in the film too, but primarily as commodities; Jean tries to use one as rent, and later gets $400 for it from a fawning Italian patroness. While in her apartment, he marks up a book of Man Ray photographs. Like the canvas, a book can be tagged but will then contain the tag, make it mobile, absorb it into the object. This is the power and mobility of the unit, which parcels painterly expression and graffiti transgression alike into price. The unit is integral to television: commercial, program, series installment, station. The unit has survived the city’s great transformation: bar-hopping allows the contemporary denizen of New York nightlife to reenact avant-garde trajectories, now emptied of difficulty or danger, each with a different name.

A later turn of Downtown 81’s dial gives us Kid Creole and the Coconuts at The Rock Lounge. Jean and a friend bribe a limo driver with a joint, and he drives them to the entrance so they can play rich and famous, get past the bouncers. The show is hopping and the mostly white kids are dancing. Unlike DNA, this music is accessible, a mesh of calypso, salsa, hip-hop, and club music. Race is in play; performance art has utterly permeated the proceedings. The Coconuts, a group of blond girls in Tarzan-chic bikinis, flank mixed-race singer August Darnell, glad in an Inspector Clouseau-type trenchcoat, acting out a carnivalesque colonialism. Later we see James Chance and the Blacks, an avant-funk outfit with the notorious No Wave frontman, clad in green velvet tuxedo, honking away while a conventional horn section, all black, keeps time behind him. The group also incorporated dancing girls, the Disco Lolitas, gyrating to the singer’s side. From punk’s asceticism, a return of the body was underway, though this Dionysian moment would be brief.

TV Party and Downtown 81 index an avant-garde that was television and needed to be on television. Public-access was a variation of punk’s DIY ethic. It was accessible, in theory, to anyone. That is to say, it “democratized” the medium. As O’Brien introduced each episode, “It’s the TV show that’s a party! But it could be… a political party.” Surely. Indeed, it could have been… anything. It was pure potentiality, smart friends hanging out and goofing off. But even this seeming frivolity is a form of collective production, and a highly visible one. Not an explicit politics, then, but a mirror life of political activity, posited in the interstice between art party and bloc, at that point at which they are Same-O. As in all politics, there are adversaries. The world of commercial television just a channel away, contiguous. To the onslaught of mainstream TV, TV Party proffered an ideal world premised on the dismantling of categories and laws. In one episode, Steding perks up out of a pot haze, leaps to his feet, grabs the microphone. It is as though he has remembered that people are watching, in need of a message. “I’m not voting for anybody!” he declares. “Elections are dying! I’ve had it with elections! There’s nobody to vote for and there’s no need to vote for anybody!” He is gleeful, full of clarity. Indeed, who needs government? He already lives in utopia, one which has seceded from the rest of the country and the rest of television, everything and everyone else.

Jean has nowhere to sleep. He passes time at the Mudd Club, where he is surrounded by prattling art wastrels. These are the sinking and the sunk, the ones who are not going to make it, losing their balance of chemical intake and creative output. Walter Steding’s Dragon People plays in the club’s elevator, moving up and down. Steding appears in the film earlier on to lament the humiliations of minor success: having to carry his own equipment, an exploitative contract, no free time. “I could have made a great surgeon,” he sighs. That any of this organic activity might result in actual careers is a knowledge that lurks at the corners of the film and provides its coda. Dispirited and destitute, Jean wanders into a dark alley. A homeless woman asks him to kiss her. Jean obliges and is greeted by a fairy Debbie Harry, who confers a wish: a suitcase of money. Jean buys a Cadillac from its owner and speeds away, out of diegetic time, after handing a stack of bills to another homeless man, a final signifier of the city’s elusive, insistent poverty. And so the film ends by switching genres, to the road movie. The escape from TV-city, with its incessant distractions and disappointments, would mean a traversal of “real” geographical space, to the city’s border, its outside, and beyond. The accompanying song is “Cheree,” by Suicide, who used synthesizers and drum machines to create a kind of pulse that turns pop song into endless drone. The vocals do not follow verse or chorus, and simply repeat dazed yearnings—“Cheree Cheree… I love you…” over the surging rhythm, three thumps at a time, 1-2-3, 1-2-3…. There is no drama or telos, only repetition, overlap, one unit after another. The song is from 1977, the year in which punk simultaneously triumphed and charted an escape from itself.

Before he gets in, Jean spray-paints one of his familiar tags, “Goldwood,” on the side of the car. On TV Party Basquiat would type this neologism, among many others, on the screen using the character generator in the control room. TV graffiti: more editing in real time superimposed on the real-time image. Goldwood, Hollywood plus gold, a cheeky hint that this youthful horsing around was not devoid of ambition, not immune from making it, from suitcases of money. “Goldwood” rebrands the car, superseding that of the carmaker. This brand refers to its own capital, whether inherent or potential. Yes, potential: a predictive brand, in the same way that on TV Party Basquiat’s very visage is a predictive face. Goldwood rhymes with Rosebud.

But what at first looks like liberation is revealed as mere joyride. The car is only encircling the area that we have just seen, mapping the trajectory already laid by the highways on the island’s border. The escape route feeds into itself. The Empire State Building is visible in the distance, swiveling with the anamorphic view from the car as it hurtles forward. In the film’s final shots, the car is in the city again, World Trade Center behind it, riding under the elevated West Side Highway. The sun is coming up. He never leaves.