The Asakusa Eardrum

Keywords: ryan holmberg

When the Kantō Earthquake destroyed a district in old Tokyo, a simple pine box brought it back to life.

By the evening of September 5th 1923, old Edo was gone. At 11:58 AM on the first of that month, the Great Kantō Earthquake collapsed much of the previous centuries with a 7.9 on the Richter Scale. Of what still stood in Tokyo, very little escaped the fires that raged for two days and two nights through the timber city. The attendant human toll ran into six digits. Of the districts lost, that of the lively Asakusa was most lamented. For there, in the northeastern corner of the capital, along the Sumida River, was a place people regarded a refuge for the true in Japanese urban culture.

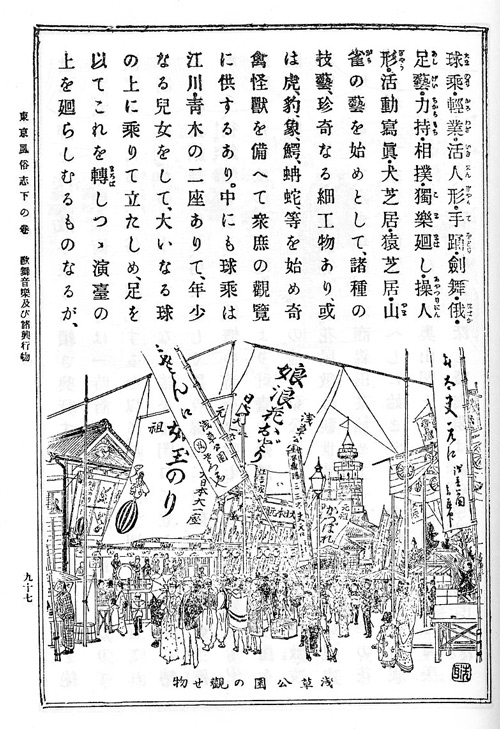

“The Misemono Spectacles of Asakusa Park,” from Tokyo fūzokushi, vol. 3 (1902), author Hirade Kōjirō, illustrator Matsumoto Senji.

In earlier times, Asakusa was elbow to chin with freak shows, clockwork automata, hydraulic automata, bawdy renditions of classics in loyalty and filial piety, figurative tableaux in bamboo basketry and dried kelp, raconteurs, thugs, and whores. In the last volume of his The Customs and Sights of Tokyo of 1902, gazetteer Hirade Kōjirō reported the following in the area: “ball riders, acrobats and cage escapers, living dolls, hand dancing, sword dancing, foot tricks (like shooting arrows and writing calligraphy), comic kyōgen, strongmen, sumo wrestling, top spinners, marionettes, moving pictures, dog theatre, monkey theatre, sparrow tricks,” and also exotic beasts like “tigers, leopards, elephants, crocodiles, and serpents.”

Modernization electrified some attractions. The coming of the cinema converted others to photograms and projected them onto walls. The expansion of the zoo at the Hanayashiki amusement park in the 1910s collected the monsters and put them in a cage.

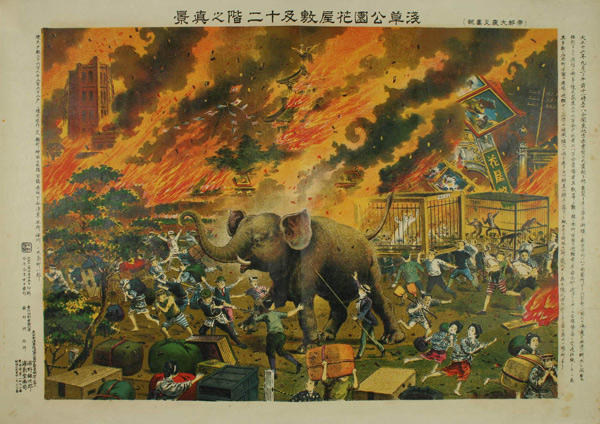

“Asakusa Park and Twelve Stories in Flames,” from The Great Earthquake Illustrated (1923), lithograph print.

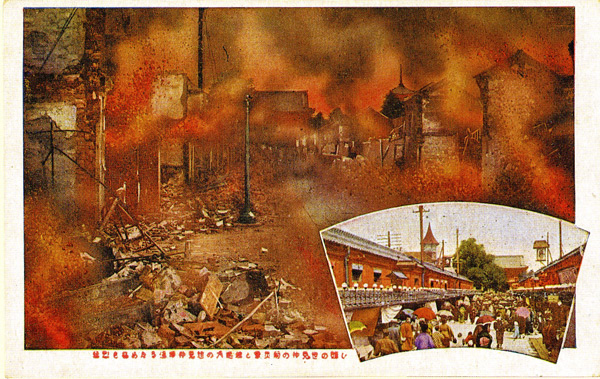

But in 1923, all was lost. What was burnable went to ashes. What was crushable was flattened. What was flesh crisped. And what could escape flew. To make room for refugees, many of the remaining animals at the zoo were poisoned. When Asakusa was rebuilt in the months following, it was done so steel-reinforced and neon-lit. Modanizumu had arrived. It was now the time of loudspeakers, the talkies, and racing car horns. But still the possibility did exist of hearing the sounds of a bygone city, the impossible made possible thanks to a private, personal, portable audio entertainment device developed in late 1923 and known as the Asakusa Eardrum.

The Asakusa Eardrum (1923), pine, 10-inch cube.

At a glance, even at a stare, the Asakusa Eardrum looks like nothing more than a small cube of planed pine. It has no external distinguishing features, but for its name written in ink on the top. One might think it held an expensive teacup, stored in boxes of similar dimension. When its lid was slid open, however, and an internal pin pressed, there began a tiny miracle—old Edo manifested in the ear.

The Asakusa Eardrum was a music box with a novel feature: interchangeable song. It was the Walkman un-electrified, before portable batteries, headphones, and magnetic tape. It was the offspring of careful Japanese carpentry and the wizardries of mechanical automata. With the lid fully removed, the guts of the machine are visible, at least in part, for wooden plates cover and protect the more delicate components. Amidst the ensemble of gears, springs, pins, clips, and rivets are two rectangular compartments, located left and right and a little below center. These are the cartridge compartments. The mouth of each compartment is color-coded: one rimmed in white pigment, the other red. The white operated by striking, the red by shaking. Various cartridge sets were available for purchase, each one named for the aural locale it recreated.

Postcard, “Asakusa Nakamise Shopping Arcade Devoured by Flames,” (1923).

The construction of these units was no less ingenious than that of its host hardware. For example, there was “temple fair” (kaichō) with the sound of small tin bells and the clinking of coins. The tin bells—miniature versions of the kind found at shrine and temple interiors, where Shinto deities or Bodhisattvas were beseeched through a small monetary offering, jangling a bell, and a clap of the hands—hung four on a thread, taught and suspended in a small half-box, a tiny open coffin. Placed within the white compartment, metal prongs would strike the thread and shake the bells with the dysrhythmia common to jostled temple-going. Into the other compartment was inserted a rectangle cartridge of similar shape but made of iron and closed. Inside were small metal discs (miniature coins), and the mechanism of the Eardrum was made to shake this box back and forth, back and forth, in regular rhythm, as if coins in an iron alms bowl waggled by a pauper monk. Thus, the sounds of “temple fair.”

And when one had tired of the simulated sounds of holy grounds, growing eager for greater worldliness, there was the option of nomiya, “bar.” For this set, the red compartment—the one for shaking—held a porcelain container holding two porcelain shapes, clattering together as flask drunkenly to sake cup. The workings of the white unit are both mystery and miracle, as they created, through the mere plucking and rubbing of small bamboo slats, sounds identifiable as vocal din, alternately rising in welcoming hollers and food orders and falling in inebriated spats. And there are others: “kabuki theatre,” “biwa hōshi” (“blind jongleur”), and “Hanayashiki” (“Flower Palace”), the last mimicking the Indian elephant and the tropical birds caged at the Asakusa zoo.

Photograph, “Gruesome Corpses of Prostitutes at Yoshiwara Pond.” (1923).

There was also a cassette pair titled “pleasure quarters.” It’s easily the queerest of the bunch. Surprisingly, it’s also the least jovial. When triggered, it made a high screech, sharp metal on metal, and a low grating moan, mimicking what? One first presumes the sound of heterosexual coupling. But so harsh and ugly? In contemporary accounts of the earthquake, one finds this: the piercing sound of air sucked out by consuming flames. And: the sound of fire engines with sirens blaring, the groan of melting bridges, falling towers, the deep roar of firestorms.

In this light, the other cassettes take on a shadowy cast. Together, they represent a whole city churned. Like claptrap houses of wood, first quake-shaken, with ceramic tableware and metal cooking implements clinking one against another as the tremors first rippled through the city, then crashing, the warm bar din now disconcerted grumble rising to panicked desperation, the zoo life scared and screaming, outside temples and shrines collapsing. Like a mean god turning a crank upon toy Tokyo, shaking it up, making some noise, and then tossing it all into the flames when the fun was done.

So too the Asakusa Eardrum, which sold poorly, was gutted of its internal mechanisms, of its tiny porcelain and metal riprap, and its pine casings sold en masse as kindling for the furo fires of one community bath.

Sources:

Markus, Andrew L. “The Carnival of Edo: Misemono Spectacles from Contemporary Accounts.” Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 45:2 (December 1985): 499-541.

Silverberg, Miriam. Erotic Grotesque Nonsense: The Mass Culture of Japanese Modern Times. University of California Press, 2006.

Weisenfeld, Gennifer. Imagining Disaster: the Visual Culture of the Great Kanto Earthquake (forthcoming).