Tools for Collective Action—Precarity: The People’s Tribunal

Keywords: Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA), People’s Tribunal, The Labor Issue, The Precarious Workers Brigade

The people’s tribunal as a format for examining systemic problems of precarity

The following co-authored account introduces and reflects on the people’s tribunal as a format for examining systemic problems of precarity. Based on the example of Precarity: A Participatory People’s Tribunal, carried out by the Precarious Workers Brigade (PWB) at the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) in London, UK in March 2011, we make a special reference to this event in an attempt to troubleshoot any future iterations of such an action. This account is also an open invitation to adopt and adapt this tool from the PWB’s toolbox, to address the ethics of collective action and institutionalized precarity. People’s tribunals, like the one proposed here, can be applied in work-related situations where systemic injustice, normalized to the point of intractability, lies beyond the reach of existing labour and employment legislation and policy.

Precarity is an adjective referring to a set of conditions, such as insecurity, instability and vulnerability, affecting both life and labour of an individual. The expression has its roots in the notion of ‘obtaining something by prayer’. The condition of precarity plays out via short-term contracts, no-contract work, bad pay, deprivation of rights and status, vulnerability to mobbing, competition and pressure, high rent, lack of accessible public services, etc. Precarity is not linked to a specific type of employment status, but manifests itself through an insecurity whereby one is at the mercy of others, always having to beg, network and compete in order to be able to pursue one’s labour and life. Precarity is the paradoxical state of being both overworked and insecure at once, regardless of being employed or not.

The PWB is a UK-based group of precarious workers in culture and education organised around the issue of precarity. We call out in solidarity with all those struggling to make a living in the current climate of instability and enforced austerity.

We come together not to defend what was, but to demand, create and reclaim:

EQUAL PAY: no more free labour; guaranteed income for all

FREE EDUCATION: all debts and future debts cancelled now

DEMOCRATIC INSTITUTIONS: cut unelected, unaccountable and unmandated leaders

THE COMMONS: shared ownership of space, ideas and resources

The PWB’s praxis springs from a shared commitment to developing research and actions that are practical, relevant and easily shared and applied. If putting an end to precarity is the social justice we seek, our political project involves developing tactics, strategies, formats, practices, dispositions, knowledges, etc. for making this happen. We inherited this hands-on, action-oriented approach from the Carrot Workers Collective (CW).

Over the past five years, this self-organised, London-based initiative has been active around issues of free labour, particularly internships, in the cultural sector. However, several circumstances converged in the spring of 2010, prompting the CW to seek solidarity with other like-minded groups. The massive bank bailouts that followed the inconceivable mismanagement of the banking sector by the previous Labour governments led to unprecedented cuts to public spending being introduced by the recently elected coalition (Con-Dem) government. Research funding cuts were only the beginning of a wider project, which appears to lead to an effective privatization of culture, arts and higher education sectors in the UK. Beyond these changes to the situation in the UK, there was a desire within the CW to broaden the group’s remit beyond internships, by framing precarity as a systemic problem present in all aspects of cultural and educational work. The reliance on a willingness to work for free in the arts, for example, means those who can afford to work unpaid are at a distinct advantage in this sector. This leads not only to the exclusion of those who cannot afford to work for free, but also perpetuates a culture of poor working conditions where unpaid overtime is the norm, the minimum wage regulations are often ignored and competition among peers becomes even more fierce.

A residency invitation from the ICA in autumn 2010 offered the CW an opportunity to open the group to other individuals and collectives. This lead to the CW putting out an open call for contributions, which brought together a diverse group of artists, activists and educators who began to map their personal experiences of precarity. The Precarious Workers’ Brigade was born. As a fledgling collective we had come together to try to deal with the many facets of precarity and at the same time investigate how, through working together as a group, we could counteract our own individualised precarious conditions. The discussions we had were heated and complex as we reflected on, for example, the romanticised view of privileged artists in search of a precarious existence and our own complicity in the reproduction of our own precarious condition. We began to gather testimonies of other people’s experiences, used forum theatre exercises and co-counselling techniques and discussed relevant film and video materials to further our understanding of the matter at hand.

We wanted to share our research and experiences in a public arena and considered the format of a people’s tribunal as a method of continuing a collective conversation that would reflect our interest in recognising the characteristics and repercussions of precarity, as well as holding the conditions that allow it to continue to account. We hosted Precarity: The People’s Tribunal at the ICA on 21 March, 2011.

What is a People’s Tribunal?

A people’s tribunal is not a trial. People’s tribunals have been used in circumstances where legal norms do exist, but their breach is not being prosecuted by the courts, for example, if the identified injustices are not illegal per se, but could and should be outlawed or if injustices cannot be grasped by the law because the existing law is unable to identify structural causes that lead to an unjust situation. Our understanding is that precarity is not a perpetrator, person, nor a crime. It is a condition brought on by a set of interrelations that connect the deeply personal and the systemic, the political and the economic. As a result, in the condition of precarity there are regular breaches of legal conventions, such as failure to provide payment, to provide proper contracts, to comply with oral agreements and to provide safe working environments. These injustices are often not prosecuted for a whole host of reasons. While some of the aspects of precarity are covered by existing law and are therefore illegal, the vast majority is not. Therefore the condition of precarity seems to lend itself to the form of a people’s tribunal that can provide a public space where voices of the implicated can be witnessed, for example, by listening to the stories of precarious workers in their own words, gestures, sounds and images.

The more we worked together to understand the complexity of precarity in tandem with the tribunal format, the more we recognised the value of the tribunal’s structure for organizing, presenting and activating the form and content of our research. Rather than taking on a role that is already scripted, the tribunal format allowed us to adapt and script our roles ourselves, as we went along. We received an overwhelming amount of personal testimonies leading to questions concerning how they could be used in the tribunal. We were keen not to abstract them into bullet points or sound bites, draining them of the real-world significance of the contributors’ lived experience.  Rather than merge many testimonies together to create more generic/fictional ones, we chose a few pertinent accounts. The rest will provide the basis for an archive, which we continue to add to and/or use in future tribunals.

Rather than merge many testimonies together to create more generic/fictional ones, we chose a few pertinent accounts. The rest will provide the basis for an archive, which we continue to add to and/or use in future tribunals.

Throughout our workshops and preparations, four themes emerged when organising the tribunal’s content. These themes formed the basis of four cases. The cases were scripted using some of the collected testimonies and presented by and to the participants in the tribunal. Evidence was brought to bear in the form of images, transcripts and objects. In some cases, the lack of evidence itself was acknowledged as significant by its very absence. Expert witnesses also testified in relation to each of the themes.

The four cases presented at the tribunal were:

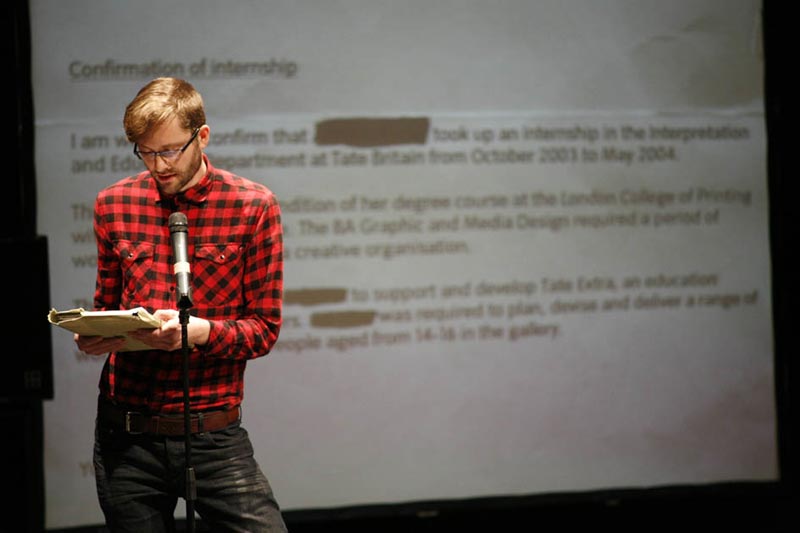

The underpaid and the unpaid.

This section was concerned with the casualisation of the labour force, whose contracts are shorter and less reliable and often only exist in the form of spoken agreements. It also looked at the commonly held misconception that people should work for nothing.

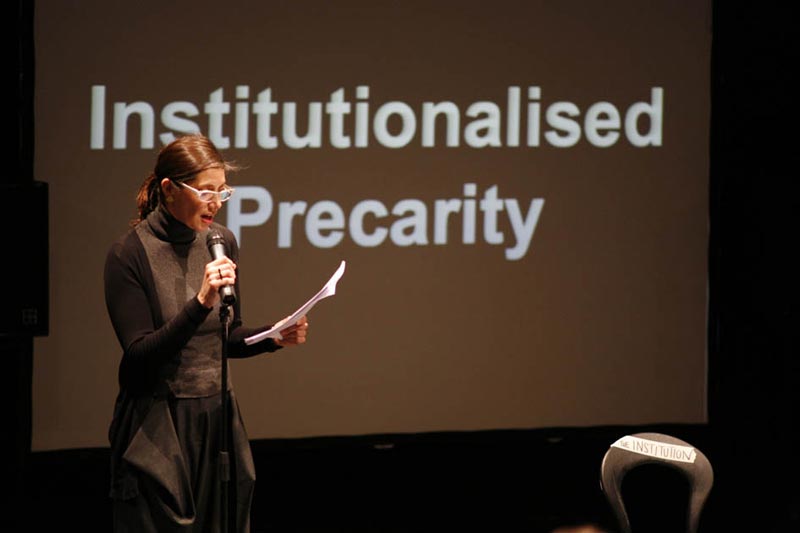

Institutionalised precarity.

In this section, we talked about institutionalised precarity in terms of the role of institutions in the production and self-replication of different aspects of precarious life, for example, poor or no pay; the exploitation of cultural workers’ willingness to work for free; the false promise of future opportunities; the expectation of long working hours; the lack of resources for production and artists’ fees; and directorships being led by marketing and branding strategies, de-prioritising engagement in the work their organisations supposedly support. We looked at both the situated and the systemic aspects of precarity that arise in our work and life experiences.

Immigration.

In this case, voices of absent contributors related experiences of precarious realities arising from constantly changing immigration policy. We looked at how visa and residency issues intersected with the other themes and compounded the difficulties faced by individuals.

Affect.

This section presented several cases that illustrated how precarity impacts on the body, mind and soul. Testimonials broke the silence on the physical and mental symptoms caused by long term casualisation and uncertainty of working conditions. As each person told their story, they asked: ‘why did I accept this situation?’

After hearing the cases, tribunal participants organised into breakout sessions to discuss the evidence, share their own experiences and begin to collectively formulate responses, judgments, proposed remedies and demands. While this public manifestation of the people’s tribunal at the ICA has come to an end, the PWB are interested in the notion of a permanent people’s tribunal and we consider our research and actions on these issues to be ongoing. We would welcome others to develop and rework this tool so that we can build further solidarity with other precarious workers, continue to highlight and hold to account, the conditions of our ‘employment’. Based on what we have learnt from our experiences of developing the tribunal format in this context, we would like to offer some points for further consideration.

Points to consider when developing a people’s tribunals on precarity:

Retain the multitude of voices, whilst ensuring the evidence is treated seriously.

The collective research process and the tribunal itself mapped multiple ‘truths’. Voices were amplified through anonymous testimony, which was heard by an audience of witnesses who became active participants in the tribunal, contributing their own experiences and reflecting on those presented. The tribunal format allowed us to keep the research alive and open to a collective process of re-reading, re-writing and re-imagining. Drawing on methods of forum theatre and the concept of law as being performed, this performative aspect allowed us to open up the evidence for further discussion. We were also concerned, however, with turning this ‘serious research’ into a spectacle, performed in a theatre space at the ICA. How can you keep the balance between the politics and poetics offered by the format of the people’s tribunal so that the evidence being presented cannot be easily ignored?

Say the unsaid – go public with what we can’t usually talk about by speaking collectively.

The whole issue of precarity relies on its normalisation and acceptance by all parties. We chose the people’s tribunal format precisely because it is useful in exploring such systemic issues and allows those who have been silenced to speak. The position of victim is one of being wronged, characterised by power structures weighted against an individual – it can be empowering to speak from this position, especially if the conditioning is not to acknowledge what is going on and to remain silent. It is also vital to implicate ourselves in institutional and other structural aspects of the issue. How can we avoid being debilitated by such an implication?

We did not anticipate the strength of the emotional aspects of the tribunal – the anger, relief, anxiety, fear. It can be difficult to talk about such issues and even more difficult to listen. It is particularly empowering to speak and listen collectively.

Create a space for the audience to become participants in the tribunal process.

When preparing for the event, we thought about the tribunal’s audience as participants. The tribunal appeals to its public through its open format allowing a direct engagement in social justice. We moved back and forth between group discussions and breakout sessions in order to create a space for voices to be heard beyond those of the facilitators, the PWB. We were there to learn from each other, through the testimony and contributions of our peers, articulated through the performative format of the tribunal. Those who attended seemed to have broadly familiar and commensurate thinking and concerns. We were united in our conviction that precarity is unacceptable. There was a yearning to move beyond consciousness raising – to move beyond representing politics and to do politics more directly.

Find ways of productively implicating yourselves and the staff of your host institution, in the tribunal process.

How can we highlight working conditions without exacerbating them? The people’s tribunal is a sensitive format that can support the anonymity of precarious workers. We intended to productively implicate the ICA in our discussion around precarity and to do so in ways that might change policy or other managerial approaches and advance the struggle against this issue. Unfortunately, this was not something we were able to explore and the initial idea of working with the ICA staff over the course of several months was never realised. The ICA managed the residency process in such a way, that we could never interact with its staff until the day of the tribunal. For us, in the entire involvement with the institution, this was the biggest missed opportunity.

Continue to open the process up, so that others can carry out their own people’s tribunal on precarity.

We invite others to develop and improve the people’s tribunal as a tool. Use our experience outlined here to add to the research and host your own tribunal. We would like to learn how you are mapping, articulating and collectively and confidently rejecting situations affected by the conditions of precarity. Perhaps in this way we could raise awareness of these increasingly prevalent conditions and have a direct input in improving our own and our fellow workers’ circumstances.

Precarious Workers Brigade have a policy of including information on the context in which their work appears:

text written July 2011; by 6 people of PWB; published in Dis magazine; text online available for free; writer fee total $0; Dis magazine employed 1 interns in 2010; 0 interns collaborated in preparing this text for publication; they are paid at $0 per hour. This text is licensed under a Creative Commons non-commercial, share alike, accreditation license.

http://precariousworkersbrigade.tumblr.com/

[email protected]